I’ve always loved trees. I love their look, their shade, the sound of wind in their leaves, and the taste of every fruit they produce. As a grade-schooler, I first planted trees with my father and grandfather. I’ve been planting them ever since. Once, as I was training to become a doctor, my wife and I tree-lined the whole street where we lived. But a dozen years ago, when I offered to plant trees at our church, one of the pastors told me I had the theology of a tree-hugger. This was not meant as a compliment.

The church was a conservative one. It believed that Scripture is the inspired, inerrant Word of God. That’s why we went there. As one member explained to me, “Once you get onto that slippery slope of liberalism, who knows where you’ll end up.”

My first reaction to the pastor’s comment was, “Maybe I’m wrong. Maybe God doesn’t care about trees.”

Back then, our whole family was new to Christianity. My daughter hadn’t yet married a pastor. My son wasn’t a missionary pediatrician in Africa, and I’d yet to write books on applied theology or preach at more than a thousand colleges and churches around the world. What did I know about the theology of trees?

But ever since I encountered the gospel for the first time in my 40s, the Bible has been my compass. So when I was called a tree-hugger, I turned to Scripture to get my bearings.

God Loves Trees

Other than people and God, trees are the most mentioned living thing in the Bible. There are trees in the first chapter of Genesis (v. 11–12), in the first psalm (Ps. 1:3), and on the last page of Revelation (22:2). As if to underscore all these trees, the Bible refers to wisdom as a tree (Prov. 3:18).

Jeff Rogers

Jeff RogersEvery major character and every major theological event in the Bible has an associated tree. The only exception to this pattern is Joseph, and in Joseph’s case the Bible pays him its highest compliment: Joseph is a tree (Gen. 49:22). In fact, Jeremiah urges all believers to be like a tree (17:7–8).

The only physical description of Jesus in the Bible occurs in Isaiah. “Want to recognize the Messiah when he arrives?” Isaiah asks. “Look for the man who resembles a little tree growing out of barren ground” (53:2, paraphrase mine).

Do you think trees are beautiful? You’re in good company. God loves trees, too. By highlighting every sentence containing a tree in the first three chapters of Genesis, one can get a pretty good sense of what God thinks about trees. Nearly a third of the sentences contain a tree.

Genesis 2:9 declares that trees are “pleasing to the eye.” This aesthetic standard does not waver throughout the Bible. Whether God is instructing his people on how to make candlesticks (Ex. 25:31–40), decorate the corbels of the temple (1 Kings 6), or hem the high priest’s robe (Ex. 28:34), the standard of beauty is a tree (and its fruits). If we were to examine the most comfortable seat in a home today, odds are that it faces a television. In heaven, God’s throne faces a tree (Rev. 22:2–3).

In Genesis 2, God makes two things with his own hands. First, he forms Adam and blows the breath of life into his nostrils (v. 7). Then, before Adam can exhale, God pivots and plants a garden (v. 8). It is here, under the trees, that God lovingly places Adam, giving him the job of “dress[ing] and keep[ing]” them (v. 15, KJV). The trees have their only divinely established tasks to accomplish. God charges them with keeping humans alive (Gen. 1:29), giving them a place to live (Gen. 2:8), and providing food to sustain them (v. 16).

Strangely enough, Scripture continuously portrays trees as things that communicate. They clap their hands (Isa. 55:12), shout for joy (1 Chron. 16:33), and even argue (Judges 9:7–15). What makes this pattern especially odd is that creatures that obviously do communicate—such as fish or birds—are virtually mute in the Bible. Over the thousands of years people have been reading the Bible, this has been passed off as mere poetry. But in the last two decades, tree scientists have discovered something fascinating about trees: They really do communicate. They count, share resources, and talk with each other using a system dubbed the “Wood Wide Web.”

Magnus Lindvall / Unsplash

Magnus Lindvall / UnsplashThe Disappearing Forest

Despite the veritable forest of trees in Scripture, most people today have never heard a sermon on trees. This was not always the case. Glance at a few of Charles Spurgeon’s sermon titles and you’ll see an indication of what people were hearing from the pulpit during the mid- to late 1800s: “Christ, the Tree of Life,” “The Tree in God’s Court,” “The Cedars of Lebanon,” “The Apple Tree in the Woods,” “The Beauty of the Olive Tree,” “The Sound in the Mulberry Trees,” “The Leafless Tree,” and so on. Spurgeon, the “prince of preachers,” had no difficulty seeing both the forest and the trees in Scripture.

Jeff Rogers

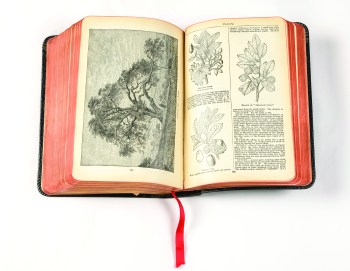

Jeff RogersNot only have trees gone missing from our sermons, they are disappearing from Bibles as well. On my shelf sits a King James Study Bible, published in Spurgeon’s day, that contains over 20 pages on the subject of trees and plants, including multiple full-plate illustrations of trees. In 2013, the same publisher released an updated printing that leaves out all these pages of commentary. In the index, it lists just three references under “tree”; the index of another, even more recent study Bible on my shelf contains no tree entries at all.

If trees were once commonplace in sermons and study Bibles, they were also fixtures in Christian literature. If we reach back over a thousand years to one of the oldest pieces of English literature, The Dream of the Rood, we will hear the story of the Passion told from a tree’s point of view.

Even in more recent times, Christian fiction writers like George MacDonald, J. R. R. Tolkien, and C. S. Lewis have infused their work with biblically rooted tree theology. Whether it is MacDonald’s picture of heaven in At the Back of the North Wind, Tolkien’s tree haven Lothlórien in Middle Earth, or how trees respond when Aslan is on the move in Lewis’s Narnia, each author paints a picture of shalom among the trees. The good guys live under, in, and around trees. They value, protect, and even talk to trees. In contrast, evil characters like Tash and Sauron are clear cutters of trees—even talking trees!

What explains the increasing absence of trees from the modern Christian imagination? The reasons are many and complex, but it most likely centers on the resurgence of the first-century heresy of dualism: God’s created world is bad, and only spiritual things reflect the glory of God. One of the chief flaws with this philosophy is that it disparages all the things God called “good” in creation. As Paul said to the Romans, you’re without excuse for believing in God if you’ve been for a walk in the woods. Through nature, we are confronted with unmistakable evidence of God’s power and glory (see Rom. 1:19-20). If trees and the rest of God’s world are inherently corrupt, Paul’s assertion is erroneous.

Getting Back to the Tree of Life

The problem with subtracting trees from our theology is that God put them in the Bible for a reason. There were two trees at the center of the Garden of Eden. One (the Tree of Life) represented humanity’s connection to the divine and the eternal. The other (the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil) represented human agency—and possible rebellion. When Adam and Eve ate from the wrong tree, they tried to cover up their crime by undressing the very trees they were charged with “dressing” (Gen. 2:15; 3:7). Their next move was to run and hide behind them (Gen. 3:8). Chapter three of Genesis concludes with Adam and Eve being banished from the Garden. What is the Bible, then, if not a story of God meeting humanity’s need for a Savior to reunite us to the Tree of Life?

Georg Nietsch / Unsplash

Georg Nietsch / UnsplashWithout trees in the Bible, the waters of Marah would have forever remained bitter (Ex. 15:25), the Giant of Gath would not have been thrown off his game (1 Sam. 17:43), and David would have missed his call to battle (1 Chron. 14:15). Deborah would have been without a place to judge Israel (Judges 4:5), and God wouldn’t have called his people to be oaks of righteousness (Isa. 61:3). There would have been no almond grove (Luz, renamed Bethel, means almond tree) for Jacob to fall asleep in and dream of a wooden ladder that spans the gulf between heaven and earth (Gen. 28:10–19), and Job wouldn’t have uttered his famous line about trees and resurrection (Job 14:7). Most importantly, without trees it is impossible to understand the Fall or Jesus’ atoning death.

Isaiah predicted that God’s people would fail to notice the “tender shoot” he had planted for their salvation (Isa. 53:2), a prediction fulfilled in the first chapter of John’s gospel. This is the scene where Philip went to Nathaniel, saying, “We have found the one Moses wrote about in the Law, and about whom the prophets also wrote—Jesus of Nazareth, the son of Joseph” (John 1:45). Nathaniel famously responded, “Nazareth, can any good thing come from there?” “Come and see,” Philip urged (v. 46). As Jesus saw Nathaniel approach, he said, “Behold, an Israelite indeed, in whom there is no guile” (v. 47, KJV). Jesus could have just as easily said, Behold, an Israel (one who has struggled with God and persevered) in whom no Jacob (trickster) is left. Nathaniel certainly got the compliment.

Earlier, Jesus had seen Nathaniel under a fig tree (John 1:48). The Bible doesn’t record what Nathaniel was praying at the time Jesus saw him, but the mere mention of the occasion let Nathaniel know beyond a shadow of a doubt that Jesus was the Messiah. Perhaps Nathaniel had pleaded with the Lord to see the Messiah in his lifetime. He might have even gone so far as to remind God of his study of the prophets in an effort to recognize the Messiah.

But Nathaniel had forgotten the words of the prophet Isaiah: “He grew up before him like a tender shoot, and like a root out of dry ground. He had no beauty or majesty to attract us to him, nothing in his appearance that we should desire him” (53:2). As Isaiah predicted, something great would indeed come out of a town named after a little tree: Nazareth!

Jesus went on to tell Nathaniel that he would see the ladder Jacob dreamed of long ago: “You will see ‘heaven open and the angels of God ascending and descending’ on the Son of Man” (John 1:51). A rescue plan involving trees had been unfolding in time, whether or not Nathaniel recognized it.

So it is no surprise that Jesus talked of trees being uprooted and thrown into the sea by faith (Luke 17:6). Nor is it any surprise that he spoke of his disciples bearing fruit (John 15:8) or instructed them to dwell in him, as fruit-bearing branches in a life-giving vine (15:4–6). As Paul put it, believers are like a branch or scion grafted onto a tree (Rom. 11:17–18).

Jesus is one tough carpenter—the kind that can heft two three-quarter-inch sheets of plywood on his own. He is hard to kill. From the moment he was born, his enemies set about trying to kill him. They tried to kill him as a baby (Matt. 2:16–18), stone him (John 10:31–39), and throw him off a cliff (Luke 4:29), but it didn’t work. Jesus could go 40 days without food, climb into the ring with the toughest opponent on the planet, and walk away a winner after three rounds (Matt. 4:1–11). There was no point in trying to drown him—he’d walk away from that too (Matt. 14:22–33).

No, the only thing that could harm the carpenter from Nazareth was a tree. Why? Because he who is hanged on a tree is cursed (Deut. 21:23, Gal. 3:13), not he who is stabbed, stoned, or burned. (Note that in Hebrew, the word for gallows and tree is one and the same.) Without trees, there is no resurrection, no Good News on Easter morning. The cross is really a tree of life chainsawed down by man’s sin. Yet Jesus’ blood caused a dead tree used as a Roman torture instrument to grow into the symbol of life everlasting—the Tree of Life. Jesus is the Tree of Life, and one day his followers will eat from the leaves of this tree and be healed (Rev. 22:2, 14).

A New Kind of Door

I started life as a carpenter. I’ve never really stopped. Over the last several years, I’ve completely re-trimmed the house I live in—doors, floors, and all.

One part of carpentry that separates the weekend warrior from the journeyman is hanging solid doors from scratch. Doors throughout time and across cultures are remarkably similar. They hang from hinges and close on a jamb. A door is topped by a header—or, as the Bible puts it, a door has two side posts and is topped by a lintel (Ex. 12:22). When the Passover Lamb’s blood was applied to these three boards at the time of the Exodus, the door locked, and the angel of death could not enter.

At a Passover celebration 2,000 years ago, Jesus made a new and very strange kind of door. To be sure, it is a narrow door. Unlike all other doorways that require three boards, it uses only two: a vertical piece and a horizontal one. When Jesus’ blood is applied to these two crossed pieces of wood, the doorway to heaven opens. There is no other way to unlock it.

Jeremy Bishop / Unsplash

Jeremy Bishop / UnsplashI believe the Bible has a forest of trees because trees teach us about the nature of God. Just like a tree, God is constantly giving. Trees have been giving life long before human beings had a clue oxygen existed. Trees give life, beauty, food, and shade. The desk I’m writing on is made of dead maple trees. No wonder God uses trees to instruct us about life, death, and resurrection. Trees, like God, give life even after death.

You’d think that Jesus might have held it against trees after he was crucified. But that doesn’t seem to be the case. On Easter morning, when Mary went down to put flowers on the tomb, her eyes were raw from crying. She looked up and saw Jesus. She did not mistake him for a soldier, bureaucrat, or merchant. She mistook him for a gardener (John 20:15). This was no mistake. He is the new Adam, back on the job where the old Adam failed—dressing and keeping the garden. His invitation to us in the Bible’s last chapter is to keep his commandments, so that we can meet him at a tree—the Tree in Life before God’s throne, with branches that bear fruit in every season and leaves that heal the nations.

An Investment in Humanity’s Future

Those who plant or protect trees because of their faith are in good company. In fact, the church where I was once suspected of tree-hugger tendencies eventually planted trees on its grounds. Moreover, the church’s logo now sports a stylized Tree of Life. I believe that this response is emblematic of what will happen when Christians rediscover the trees that God planted in Scripture and reforest their faith.

Abraham was the first person in the Bible to plant trees. At the time, Abraham owned not a square foot of land. Scripturally, tree planting started as an unselfish act of faith. “And Abraham planted a grove in Beersheba, and called there on the name of the Lord, the everlasting God” (Gen. 21:33, KJV). By virtue of the way that trees work, Abraham’s act made the world a better place.

Today, we understand a tree’s role in the global oxygen, carbon, and water cycles. But all that was unknown to Abraham. Nonetheless, Abraham’s grove is a blessing to all the families of the world (see Gen. 12:3). Abraham planted for the next generation, and the one after that.

The Old Testament ends with an admonition to think long-term and to give thanks for those before us. The hearts of one generation are to turn toward the hearts of the next, and vice versa (see Mal. 4:6). Only the Lord knows the mind of a man, but in Abraham’s case, the planting and protection of trees were tangible evidence of what was in his heart. Long-term thinking is godly. Short-term thinking is not. Perhaps this is another reason why the first psalm says that the righteous man resembles a tree.

Indeed, the writer of the first psalm offers one of the clearest insights into God’s thinking on trees. King David danced and shouted for joy when the ark containing the Bible, a jar of manna, and an almond branch was moved to the tabernacle he had prepared. He wrote a song of thanksgiving to celebrate the occasion. The song looks forward to the second coming of the Messiah. Even the trees join in the celebration: “Let the trees of the forest sing, let them sing for joy before the Lord, for he comes to judge the earth” (1 Chron. 16:33). The Bible says that many people will hide under rocks to avoid judgment in the Second Coming—but not the trees. They finally get their day in court, and they know exactly what the verdict will be.

I believe that Jesus will return to judge the living and the dead, as the Bible says. But what about those who argue that the Lord’s return relieves us from any concern about trees? “All resources,” they say, “should be put toward evangelism.”

If someone believes this and acts accordingly, I say, “Amen!” But too often this sentiment is expressed with all the sincerity of Judas Iscariot advocating for the poor as Mary anointed Jesus with fine perfume (see John 12: 1–8).

Trees are God’s investment in humanity’s future. They are the only living thing to which God gives a ring on each birthday. Only he knows the exact timing of Christ’s return. I hope it is tomorrow morning. But, in the meantime, I’ll plant trees that will take a century to grow, and I’ll try to spread the gospel like there’s no tomorrow.

Matthew Sleeth, MD, is a speaker, author, and executive director of Blessed Earth, an organization promoting stewardship of creation. His next book, Reforesting Faith: What Trees Teach Us About the Nature of God and His Love for Us (WaterBrook), releases in April 2019.

Have something to say about this topic? Let us know here.