In 1936, a 27-year-old man named Lesslie Newbigin set out from England for India to share Christ among the Hindus. Newbigin faithfully ministered in India for the next 38 years. When he returned to his home country in 1974, he found it had become a drastically different country from the one he left. It was becoming increasingly a post-Christian nation, one in need of a fresh missionary encounter.

Cultural Apologetics: Renewing the Christian Voice, Conscience, and Imagination in a Disenchanted World

HarperCollins Children's Books

240 pages

It was during this time that Newbigin wrote what is now considered a modern classic on mission, Foolishness to the Greeks. In his book, he explores the most crucial question of our time. He asks:

What would be involved in a missionary encounter between the gospel and this whole way of perceiving, thinking, and living that we call “ modern Western culture ”?

This is the question to be asked of any post-Christian culture. Newbigin is interested in how we can talk to others about Jesus in a way that is understood by those becoming further and further removed from Christianity’s language and worldview. This is the “missionary encounter” Newbigin has in mind. And while Newbigin’s question is essential for us to answer today, it also leads us to an even bigger question: What do you make of Jesus Christ?

Newbigin understood that every person in every culture is shaped by what sociologist Peter Berger calls “plausibility structures.” Berger says every culture has a collective mindset, a collective imagination, and a collective conscience. This combined outlook shapes the culture’s view of the world and what is judged within the culture as plausible or implausible. Is something a genuine possibility … or just an outrageous idea?

Newbigin knew that we fail to have genuine missionary encounters if we fail to understand those we seek to reach with the gospel. Our words and our message must be understandable. In a post-Christian society, talk about Jesus is no different from talk about Zeus or Hermes. We sound foolish, and our beliefs appear implausible and meaningless.

Engaging culture

How can we have a genuine missionary encounter in our culture? This is the question that drives the work of cultural apologetics. The term “cultural apologetics” itself has not been widely used until recently, but little has been written on how we are to understand this new kind of cultural engagement. Ken Myers, the producer and host of Mars Hill Audio Journal, offers the following definition:

Traditional apologetics is concerned with making arguments to defend Christian truth claims, and has often addressed challenges to Christian belief coming from philosophical and other more intellectual sources. The term “ cultural apologetics ” has been used to refer to systematic efforts to advance the plausibility of Christian claims in light of the messages communicated through dominant cultural institutions, including films, popular music, literature, art, and the mass media. So while traditional apologists would critique the challenges to the Christian faith advanced in the writings of certain philosophers, cultural apologists might look instead at the sound bite philosophies embedded in the lyrics of popular songs, the plots of popular movies, or even the slogans in advertising ( “ Have It Your Way, ” “ You Deserve a Break Today, ” “ Just Do It ”).

Notice that, according to Myers, the cultural apologist is concerned with truth, argument, and the plausibility of Christianity. The main point of contrast between the traditional apologist and the cultural apologist has to do with the kinds of evidence utilized in making a case for Christianity. For the traditional apologist, academic sources—such as philosophy, science, and history—are prioritized in providing evidence for arguments. But for the cultural apologist, cultural artifacts—illustrations from the world of music, art, sports, entertainment, social relations, and politics—are paramount.

Some are less enthusiastic about the emergence of cultural apologetics. William Lane Craig, a traditional apologist par excellence, claims cultural apologetics constitutes an entirely different sort of apologetics than the traditional model, since it is not concerned with epistemological issues of justification and warrant. Indeed it does not even attempt to show in any positive sense that Christianity is true; it simply explores the disastrous consequences for human existence, society, and culture if Christianity should be false.

According to Craig, the cultural apologist is not concerned with the truth, plausibility, or justification of Christianity, but merely with showing the disastrous consequences of a godless world. I disagree.

My proposed definition for the task of cultural apologetics is broader than, though still inclusive of, Myers’s and far more positive than Craig’s. I define cultural apologetics as the work of establishing the Christian voice, conscience, and imagination within a culture so that Christianity is seen as true and satisfying. How does this conception of cultural apologetics fit into the discipline of apologetics and relate to the debates over apologetic method, cultural engagement, and worldview analysis?

Regarding the question of apologetic method, my proposed definition of cultural apologetics is neutral, and I believe compatible, with many of the prominent approaches. One can be, for example, a classical apologist, an evidentialist, a cumulative case apologist, a presuppositionalist, or a Reformed Epistemologist and still employ the approach suggested in my book. The method suggested here is more general and inclusive than the oft-debated question of which epistemology best fits apologetics.

A more full-bodied apologetics

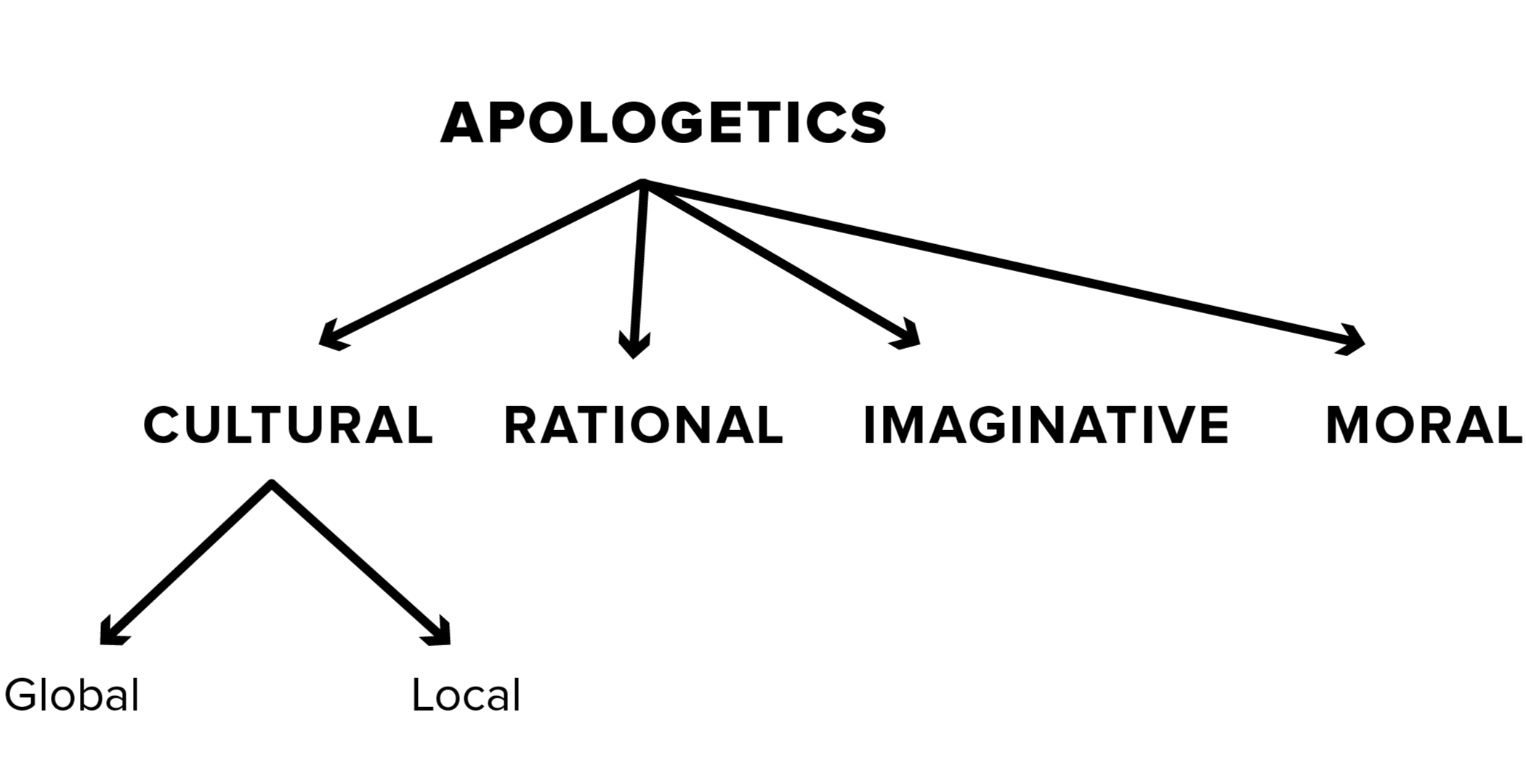

Since the Enlightenment, apologetics has primarily been conceived as a defense of the reasonableness of Christianity. With the demise of Enlightenment rationality in the 20th century, alternative models of apologetics have been proposed. Many of these newer proposals resist the reductionistic impulse of modernity, seeking a return to an integrated, and more ancient, way of conceiving the task of bearing witness. We now read of apologetics beyond reason, joy-based apologetics, imaginative apologetics, moral apologetics, sapiential apologetics, popologetics, and more. With the flourishing of new ways of conceiving apologetics, it will be helpful to provide a taxonomy of the discipline in order to locate my proposal.

Approaches to apologetics that begin with (or focus primarily on) reason or the imagination or the human conscience are classified, accordingly, as rational, imaginative, or moral apologetics. Cultural apologetics acknowledges all of these approaches and integrates them into a vision of what it means to be an embodied human that shapes and is shaped by culture, offering what I think is a more realistic and compassionate approach to apologetics. The cultural apologist affirms man’s rational nature but situates it within a more comprehensive account of what it means to be human. I claim a new lane then for cultural apologetics as I conceive it (see figure 1.1).

In addition, a cultural apologist operates at two levels. First, she operates globally by paying attention to how those within a culture perceive, think, and live, and then she works to create a world that is more welcoming and thrilling and beautiful and enchanted. Secondly, she operates locally, removing obstacles to, and providing positive reasons for, faith so individuals or groups will see Christianity as true and satisfying, plausible and desirable.

FIGURE 1.1: Cultural Apologetics and the Discipline of Apologetics

The global component to cultural apologetics needs to be distinguished, on the one hand, from the debate over Christ’s relationship to culture, a debate framed largely by H. Richard Niebuhr’s 1951 book Christ and Culture, and, on the other hand, the activity of worldview analysis championed by Francis Schaeffer, Nancy Pearcey, and James Sire.

Regarding the relationship between Christ and culture, the cultural apologist finds insight from all of Niebuhr’s five possible postures (Christ against culture, of culture, above culture, in paradox with culture, and as the transformer of culture) yet need not endorse any one position as definitive. While I find taxonomies like Niebuhr’s somewhat helpful, I do not explicitly endorse any one of his positions. I think the actual relationship between Christ and culture is more nuanced than any of these five postures, and to adopt one over another is to risk painting with too broad a brush.

I do think, however, that James Davison Hunter’s “faithfully present within” is the most defensible approach or posture toward culture for the Christian as well as the cultural apologist. I adopt Hunter’s “faithfully present within” culture approach, augmented by Andy Crouch’s insight that Christians are called to be creators and cultivators of the good, true, and beautiful.

Alternative accounts of cultural apologetics could be developed that explicitly endorse one or another of Niebuhr’s possible positions on Christ and culture. Rod Dreher’s Benedict Option, for example, suitably developed, could be understood as a cultural apologetic from a posture of “Christ against culture.” While I find such an approach problematic, I do think it would count as a version of cultural apologetics. By contrast, I think Kevin J. Vanhoozer’s sapiential or theodramatic proposal for apologetics is closest to my own, as he seeks to “demonstrate the truth of Christianity (the theodrama, not a theoretical system) with our whole being: intellect, will and emotions.”

Truth and desirability

The cultural apologist is also deeply interested in the many worldviews found within culture and how they find expression in the cultural goods produced and consumed by others. Each of these topics is important for the first task of the cultural apologist—the task of understanding culture. I do a fair amount of worldview analysis in my book. Any cultural apologetic worth its salt will do likewise.

The cultural apologist does not stop with understanding, however. The cultural apologist works to awaken those within culture to their deep-seated longings for goodness, truth, and beauty. Part of that process involves engaging with and working within the culture-shaping institutions—the university, the arts, business, and government—to help others see the reasonableness and desirability of Christianity. Worldview analysis is necessary but not sufficient for a cultural apologetic.

The cultural apologist works to resurrect relevance by showing that Christianity offers plausible answers to universal human longings. And she works to resurrect hope, creating new cultural goods and rhythms and practices that reflect the truth, beauty, and goodness of Christianity. To summarize, cultural apologetics is defined as the work of establishing the Christian voice, conscience, and imagination within a culture so that Christianity is seen as true and satisfying, and it has both a global and local component.

This definition allows—even necessitates—the use of philosophy, science, and history as well as the creation of new cultural artifacts in making a case for Christianity. Broader than Myers’s characterization of cultural apologetics, and contrary to Craig, cultural apologetics is concerned with the truth and justification of Christianity. Cultural apologetics must demonstrate not only the truth of Christianity but also its desirability.

Paul M. Gould teaches apologetics in the College of Graduate and Professional Studies at Oklahoma Baptist University and is the founder of the Two Tasks Institute. This excerpt is taken from his most recent book Cultural Apologetics by Paul M. Gould. Copyright © 2019 by Zondervan. Used by permission of Zondervan. www.zondervan.com.