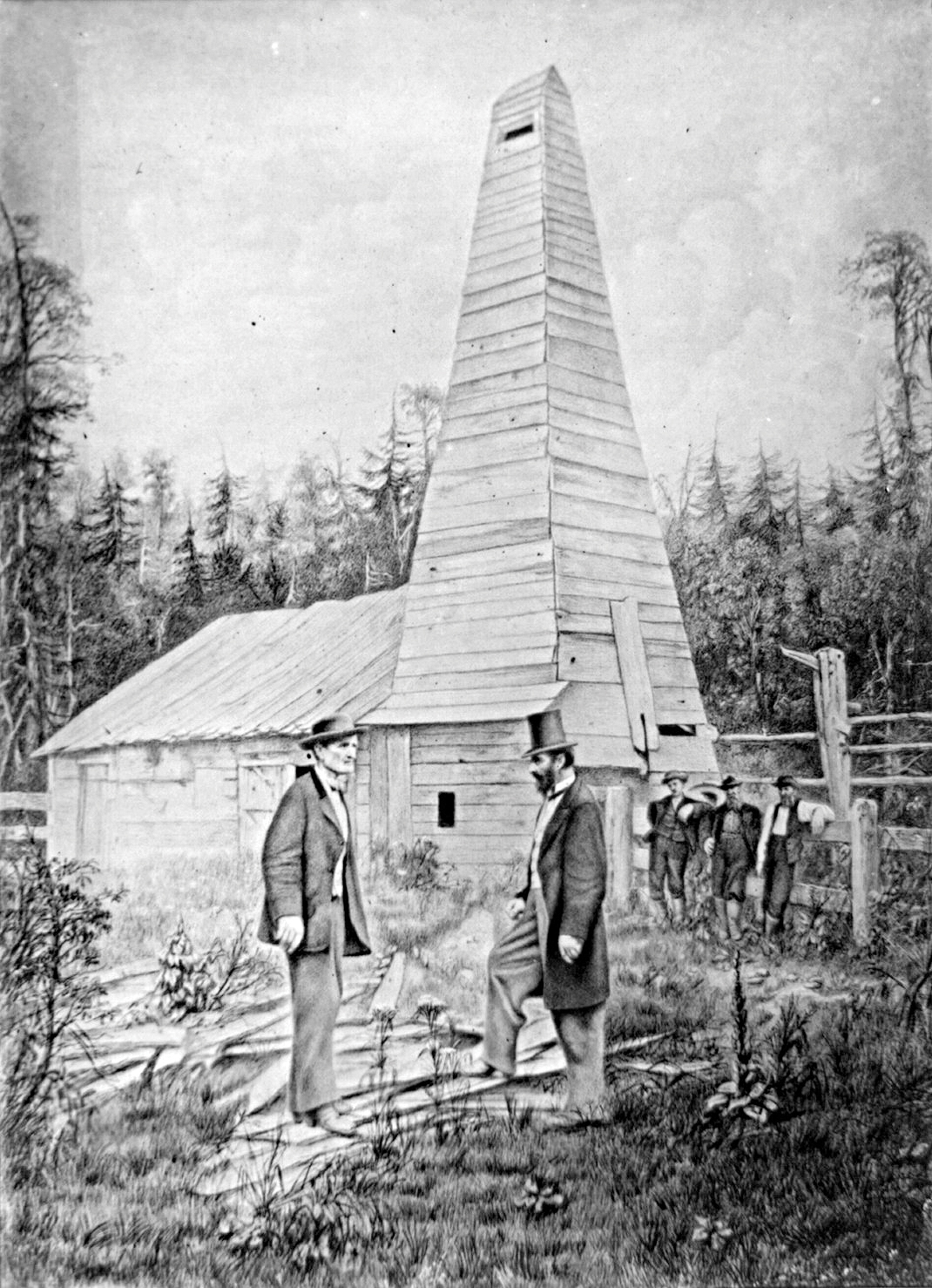

By August 27, 1859, New England railroad conductor Edwin L. Drake had been spending borrowed money for months, and it was running out. His steam-powered drill had bored 69 feet into the rock near Titusville, Pennsylvania, at the rate of three feet a day, and he had yet to strike oil. His employer, America’s first petroleum exploration company, had given up on him. When Drake and his crew went home for the night, they were already accustomed to being the punchline of local jokes.

The next day, one of Drake’s men spotted black liquid bubbling up in their well, and they began pumping it by hand into a washtub. What followed was arguably the most rapid economic and cultural transformation of the world.

The oil boom Drake triggered was accompanied by a flood of superlatives about the wonders, mysteries, and splendor of what was known at first as “rock oil.” Most immediately, Drake’s discovery offered America and the world affordable light. Kerosene—which could be made from petroleum—rapidly became the low-cost choice for lamp oil (its main competitor was pricey whale oil). Within two decades, kerosene had brought artificial lighting to city streets and to nearly every home in America.

Celebratory language continued into the early 20th century, as petroleum products found revolutionary new uses as lubricant and, eventually, as fuel for motor vehicles. Geologists, businessmen, politicians, poets, and songwriters speculated on what this new discovery meant for America and humankind.

Pastors and theologians weighed in, too. For Presbyterian minister S.J.M. Eaton of Franklin, Pennsylvania, the sudden profusion of drilling sites along nearby Oil Creek was not the result of chance. In Eaton’s view, God put vast pools of oil in the ground but kept it from man until just when we needed it to lift us out of the sin and trauma of the Civil War. In his 1866 book, Petroleum: A History of the Oil Region of Venango County Pennsylvania, Eaton wrote: “Who can doubt but that in the wise operations of God’s Providence, the immense oil resources of the country have been developed at this particular time, to aid in the solution of the mighty problem of the nation’s destiny?”

The year after Drake’s discovery, another historian named Thomas A. Gale published a book on oil that opened with a quotation from the Book of Job, where the tormented Job was longing for the return of God’s blessings, “when my steps were washed with milk, and the rock poured out for me streams of oil” (29:6, RSV). The verse probably references olive oil, but for early celebrants of petroleum, it seemed to apply far more directly to their divine gift from the ground. Historian Darren Dochuk, whose new book Anointed With Oil chronicles the intertwining paths of Christianity and crude, has noted that “many of the aspiring men who moved to the oil region of Western Pennsylvania after the Civil War did so armed with a certainty that they were chasing something from God.”

Nineteenth- and early 20th-century adults in Chautauqua assemblies, the era’s equivalent of TED Talks, learned from Alexander Winchell’s 1890 geology text that coal—the fossil fuel that launched the industrial revolution—was also a gift from God. It was laid down, according to Winchell’s Walks and Talks in the Geologic Field, for the benefit of man, who “is the fulfillment of the prophecy of the ages.”

Drake Photo Courtesy of Wikimedia Common

Drake Photo Courtesy of Wikimedia CommonWithin a century of Drake’s discovery, America had powered itself to world dominance—with oil fueling the engine of its growth and prosperity. Of course, the blessings of oil have never been equitably enjoyed. In an economy as diverse as that of the United States, extractable fossil fuels and minerals have generally been a boon for most of the population. In countries with less diverse economies or with more authoritarian leaders—think the Democratic Republic of the Congo or Iraq—abundant natural resources have more often been linked to conflict and widespread poverty, a phenomenon economists call the “resource curse.”

Nonetheless it is difficult to fault early optimism about the potential of fossil fuels to lift mankind to new heights of flourishing, because they did. After biblical times, the earth’s population edged slowly upward to around a billion until the late 18th century, when economic and technological advancements, enabled by coal and then oil, lengthened life expectancies and sent the population soaring on a near vertical trajectory to 7.7 billion today.

Unquestionably, for our forebears and for so many of us, oil indeed has been a gift from God. Why then, in the public square today, are oil and other fossil fuels increasingly spoken of as the source of looming catastrophe, like an addictive substance from which we are anxious to wean ourselves?

Last year, 13 government agencies from NASA to the Department of Commerce endorsed a report with dire warnings that the carbon dioxide byproduct of burning fossil fuels is layering the earth with a heat-trapping blanket, raising temperatures and sea levels. In 2016, United Nations member countries ratified a new approach to fighting poverty that, in part, prioritized helping the poor in countries without the resources to adapt to a warming earth.

Americans are far from unified on our views of climate change. Yet various surveys show a growing majority are both worried about the trend and see human activity as its likely cause. Evangelical Christians, on the whole, remain skeptical but are becoming less so; half say that global warming is happening and a quarter say humans are partially to blame, according to 2015 research by Pew. (A 2013 LifeWay study found that more than four in ten Protestant pastors “believe global warming is real and man made.”) And in a 2015 encyclical letter both lauded and criticized by Christian communities, Pope Francis suggested that ignoring climate change is tantamount to ignoring the poor.

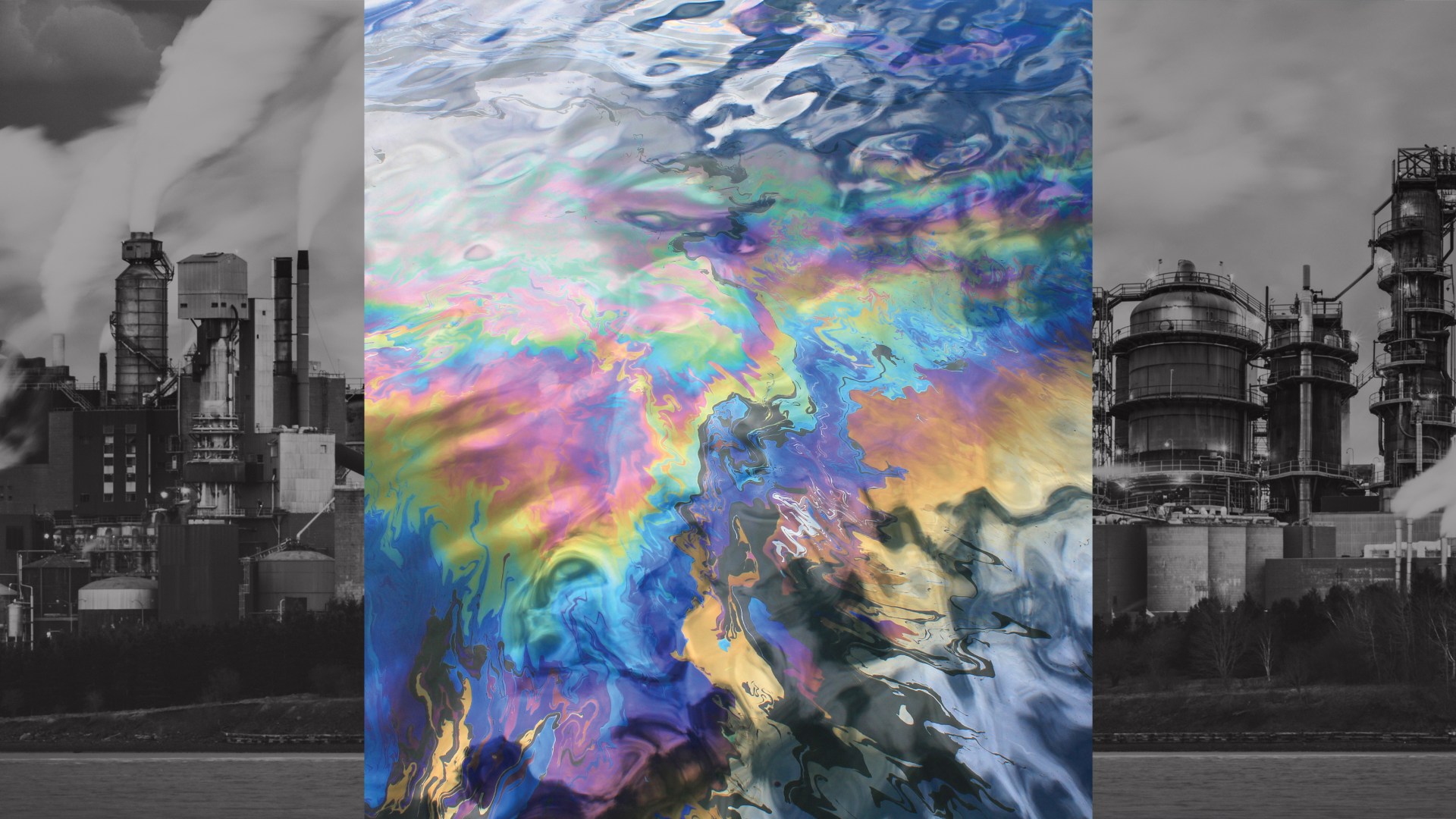

Concerns about climate change aside, our consumption of oil products in particular has had a host of other less-disputed consequences. Plastic waste from our packaging-laden economies is filling our oceans to the tune of between 5.3 million and 14 million tons a year by some estimates—most of it from trash dumped on the ground and in rivers in developing countries. Researchers are only beginning to glimpse the impacts of microplastics, barely visible particles that are swirling in the oceans and that researchers this year found raining from the air in France.

Even our well-intended efforts at recycling—the fallback creation care practice for so many of us (“At least I recycle”)—appear to be failing. China, where we sent most of our recyclables until now, announced major restrictions last year on how much paper and mixed plastics it would accept. The move has left much of America with almost no market for recyclables, prompting some cities to stop recycling altogether.

If we take a step back from our daily dependence on oil and our partisan views toward its place in our lives, the larger story arc is difficult to miss: As the God-appointed stewards of creation, we were handed one of the most priceless treasures from the depths of the earth and we fell in love with it. In ways deliberate and unwitting, we placed more and more of our hopes in its potential, until our union with oil became so intimate that it stretched our technological, theological, and social imaginations to think we could ever exist otherwise.

Oil in our blood

Every one of us is a child of oil and its material offspring. The moment we are born in a modern hospital, we are wrapped not in swaddling clothes, as Jesus was, but in oil, notes environmental scholar Vaclav Smil in his book, Oil. The first things we likely encounter as newborns are surgical gloves, flexible tubing, catheters, IV containers, and other trappings of sanitary health care—all made of oil-based plastics, as is the housing of the many computers and electronic instruments that monitor our well-being.

Our trip from the hospital to a well-lit and heated home will likely be in a car fueled by gasoline on roads paved with asphalt. Unless we are organic and local-food movement devotees, what we eat will have come from crops fertilized with fossil fuel derivatives and delivered to our homes on trucks or giant cargo ships from distant lands.

There is no denying oil’s awesome power, harnessed from solar energy sequestered in simple ocean organisms that sank over eons to the sea floor. Under intense pressure, this dead carbon formed deposits that when mined and refined have such pent-up strength—as petroleum engineers like to tell it—that a mere teacup of gasoline can move a 1,000-pound vehicle a mile up a mountain road.

But as the 20th century brought population growth, technological and agricultural wonders, and wars on unprecedented scale, oil became less of a marvel and more of a “given” in our society. If anything, we lost sight of its miraculous and gift-like nature and came to take it for granted.

Instead, Americans celebrated the automobile and the freedom and mobility it brought. Popular songs lauding the “Merry Oldsmobile” of the early 20th century and the “Little GTO” of the postwar baby boom sounded almost like psalms of praise for the almighty car. Such hymns persist today in musical worship of the iconic truck. “Thank God for the red words Jesus said,” sings Kyle Thomas Nunn in a hard-driving country anthem. “Thank God for trucks.”

Iconic images of the oil industry itself have become fundamental parts of American identity. “They don’t wash out with the mud,” asserts Montana country music singer-songwriter Eli Hundley, proclaiming his love for oilfield work. “It’s in our American blood.”

And yet that oil-rich “blood” is no longer reserved for the developed world. Beijing, New Delhi, Bangkok, and many other Asian cities are choked with dangerous smog as the region’s growing middle class plays catch-up with the West in consumption. The Asia Pacific region has already overtaken the West in carbon dioxide emissions, which many experts see as a tipping point of sorts toward inevitable sea-level rise, droughts, and what Texas Tech climate scientist Katharine Hayhoe and others refer to as “weather on steroids.”

Hayhoe and her husband, Andrew Farley, are evangelicals whose book A Climate for Change argues that God’s gift was in creating a planet whose atmosphere was perfectly suited to human life. But by pouring greenhouse gasses into that atmosphere, we have upset the balance, essentially defiling the gift.

Fruit of the Spirit, fruit of the earth

Assuming, for argument’s sake, that the vast majority of climate scientists are correct in their view that humans are warming the world, it’s difficult then not to ask: Could we have done anything differently up to this point? After all, serious research into atmospheric warming didn’t begin until the mid-1900s, so it would be uncharitable to accuse 19th-century industrialized nations of willfully disregarding the global consequences of carbon emissions.

Humans were polluting the air for hundreds of years before the Industrial Revolution, and history suggests we have long had an intuitive—if unscientific—sense that it was bad for us. The dangers of dirty air were contemplated as early as A.D. 61, when Seneca wrote about the “oppressive atmosphere” of smoke shrouding ancient Rome. The Romans allowed smoke pollution lawsuits, and more than a thousand years later, England made modest attempts to limit the burning of coal under Queen Elizabeth I. Large-scale organized campaigns to curb air pollution eventually materialized in the mid-1800s, when the coal-hungry steam engine was supercharging the world’s economy and coating neighborhoods in London, Chicago, and St. Louis with black soot.

Still, clean air concerns were almost entirely localized until recent decades. The notion that emissions could threaten the entire planet has only recently gone mainstream. But even if science and popular perception failed to raise sufficient alarms about climate change, was there nothing else to check our consumption of fossil fuels—and in particular our consumption of them as Christians?

There probably was. In the throes of the energy crisis in 1980, a man named George Sweeting, then president of Moody Bible Institute, sat down to write an essay for this magazine urging Christians to consume less. Like many Americans, Sweeting was worried that the world would soon run out of oil. Advances in oil extraction technology have deferred such concerns today, but his call feels just as timely as climate change and mounting waste dominate conversations.

“We buy things that are convenient. We eat more than we need. Expensive packages and containers become trash,” Sweeting wrote. “As victims of an easy lifestyle we have unthinkingly perpetuated a problem that is fast becoming a crisis. Somehow, we have to convince ourselves that even though things seem right, something is very wrong.”

Whether intentional or not, Sweeting’s essay was informed by the apostle Paul’s list of the fruit of the Spirit in Galatians 5:22–23, arguably the simplest and most all-encompassing description of true Christian character. Paul not only makes the case that a life of love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness, and self-control is the ultimate goal of the Christian but also that such a life is only fully possible through the inner work of the Spirit. These postures are to govern our every relationship—with one another, with God himself, with our resources, and with the created world around us. And when our behaviors stem from these postures, Paul says, we’ll have no need for laws to tell us what to do because we’ll already be outperforming the law.

If Paul is correct, then the fruit of the Spirit may be the gold standard governing how we consume God’s most precious natural gifts, such as fossil fuels and metals—or how we use any treasure, for that matter, such as an unexpected inheritance or a suddenly valuable piece of land on which a church building sits.

A loving posture toward our neighbors, for instance, would among other things certainly rule out binging on precious resources for our own benefit at the expense of others. “Wasting energy is as much an act of violence against the poor as refusing to feed the hungry,” Sweeting wrote. Along the lines of self-control, Sweeting argued that Christians must be examples of those “who restrain our self-desires.” Seeming to make the case for patience, Sweeting argued that exploitation is the natural result of “greed and haste” when we “take too much too fast.” In an essay accompanying Sweeting’s in the same 1980 issue, evangelical philosophy professor Loren Wilkinson seemed to also have an attitude of patience in mind, writing:

Good stewardship does not place on the future greater debts than it inherited from the past. This principle is particularly important in considering our use of nonrenewable resources like metals and fossil fuels. It suggests that if we use those things, part of their use should be diverted to establishing a substitute the future can use.

One could probably extend Sweeting’s and Wilkinson’s logic today and argue, for example, that an outlook of joy and contentment would ask whether we really need that jet-fueled international vacation this year, whether we really need quite so large a house to heat and cool, or whether we really need the latest cellphone.

Acts of the flesh

Whether or not we have individually demonstrated the fruit of the Spirit in our consumption of fossil fuels over the past two centuries, the story of the oil industry itself is replete with “the acts of the flesh”—what Paul posed as the opposite of Christian living. History echoes Old Testament accounts of gold and other treasure that, in the service of corrupt kings and ordinary human greed, became idols that eventually invited God’s wrath.

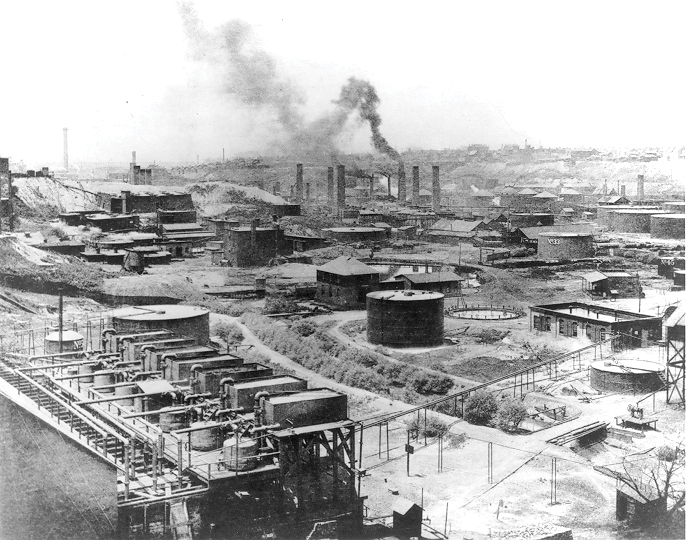

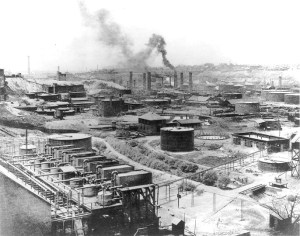

Photo Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Photo Courtesy of Wikimedia CommonsThe first oil king was John D. Rockefeller. Born 1839 in upstate New York to a pious mother and an unscrupulous cad of a father, Rockefeller was a devout Baptist. He launched and quickly dominated the oil refining and transportation businesses. But Rockefeller was a flawed godly king, accused by critics of poor labor practices and cutthroat and deceptive business dealings. He consumed everything in his path like the giant octopus portraying him in newspaper cartoons of the day, and eventually his Standard Oil Co. was dismantled by the US Supreme Court as an illegal monopoly.

Many others were overcome with “oil fever” and turned away from God. Tales of stock swindles, oil field murders, and boom-and-bust town chicanery reveal a people embracing false idols, bewitched by the promise of wealth. Only six years after Drake’s discovery, William Wright was lamenting in an 1865 book, The Oil Regions of Pennsylvania, that “in Petrolia, the church universally believed in is an engine-house, with a derrick for its tower, a well for its Bible, and a two-inch tube for its preacher.”

As with our stewardship of most of God’s good gifts, of course, our relationship with oil is a complex mix of vice and virtue. The oil industry has been exploited by some but, at the same time, it birthed a new era of philanthropy in the United States. Rockefeller’s charitable giving to public health, higher education, and Baptist missions helped transform entire segments of American society. So too did the philanthropy of other oil barons, including J. Howard Pew, whose contributions supported seminaries and Billy Graham’s ministry and subsidized the founding of Christianity Today.

That the oil industry has done so much good may explain, in part, why calls for environmental stewardship are often met with claims that to leave fossil fuels in the ground is tantamount to rejecting the bounty that a divine creator put there for our use. Energy writer Alex Epstein argues in The Moral Case for Fossil Fuels that turning away from oil would deny people in the developing world the same gifts that built and succored the West. The Cornwall Alliance, a right-of-center network of Christian scholars in diverse fields, affirms on its website “that one way of exercising godly dominion is by transforming raw materials into resources and using them to meet human needs.” To leave such bounty in the earth, the group asserts, is as wrong as it was for the laborer in the Gospel of Matthew who hid his wages in the ground rather than investing them in a quest for abundance (25:14–30).

Greener idols

The Cornwall Alliance’s arguments are persuasive in many ways: There’s no denying that the gifts of oil and other fossil fuels have enabled countless other “good and perfect” gifts that, as Scripture points out, came in some way or another from God. Their critique of carbon haters is that to suddenly change the rules of the energy game and deprive the rest of the world the quality of life that Americans enjoy is not especially loving.

Outside some extreme voices, however, the green energy crowd isn’t exactly preaching a message of privation. Their rhetoric often rings with almost the same blessing-for-all euphoria as 19th- and 20th-century celebrations of oil. The Sierra Club’s summary of a congressional proposal for a “Green New Deal” is an example. The excited rhetoric with which Eaton described oil in 1866—marshaling words like “bounty,” “immense,” and “mighty”—can be heard echoing in an online Sierra Club explainer titled “What is a Green New Deal?” The plan is “a big, bold transformation of the economy to tackle the twin crises of inequality and climate change,” the group writes. “It would mobilize vast public resources to help us transition from an economy built on exploitation and fossil fuels to one driven by dignified work and clean energy.”

Green New Deal evangelists root their hope less in a particular resource than in human ingenuity. In this, many climate activists and climate skeptics share a common belief: Whether mankind must act now to save the planet or whether, guided by market forces, mankind will eventually adapt to whatever the earth serves up, human progress will prevail.

But even if we do someday innovate a door to a distant, carbon-lite future, we’ll be just as prone to turn whatever miraculous new gifts it holds into idols. In truth, while wind turbines and solar panels and electric cars are also good gifts from God, our excited anticipation of such technologies is often as much about dodging the need for self-constraint as it is about caring for creation. We are eager for anything that doesn’t disrupt our consumer lifestyles.

Economic analysts suggest that at least some greater transition to alternative fuels is increasingly viable. Renewable energy has finally become cost-competitive with conventional fuels, and even oil giant British Petroleum is in what its CEO calls “a race to lower greenhouse gas emissions” as its own scientists expect renewable energy to overtake traditional sources within two decades.

But as Christians debate the risks of climate change and the need for action, we must be careful not to replace adulation of oil and the progress it fueled with adulation for new technological innovations. Alternative energy certainly is an important tool in the creation care toolbox, but the hope that yesterday’s technology will easily be replaced with acres of solar panels and wind farms may lead to disappointment and missed opportunities to adopt a more prudent lifestyle.

Baptist Theological Seminary Bible professor Mark Biddle offers perhaps the best warning for those who would substitute temples to oil with temples to new technology: “Christianity does not offer a utopian vision of perfected human society,” Biddle writes in his 2005 book, Missing the Mark: Sin and Its Consequences in Biblical Theology. “It issues a call to the kingdom of God.” For Biddle, progress is the myth of a society “marked by arrogant overconfidence in human capabilities.”

Human overconfidence is not just a religious concern but also a technological one. Manufacturing wind turbines takes massive amounts of energy, and transporting the blades, steel, and concrete to building sites requires large, diesel-fueled trucks. Likewise, the manufacture of alternative transportation sources, such as electric and hybrid cars, demands staggering amounts of energy and rare earth metals whose production has particularly nasty environmental side effects. And many forms of green energy and transportation remain expensive and out of reach for low- and middle-income Americans.

Clearly, we will not be given solutions to climate change or to the global trash epidemic absent hard choices and sacrifices. And no sacrifice from the church alone will be enough to turn the tide without significant efforts from industry and the massive global supply chains that are only responding to current consumer habits and even government regulations. (Who has ever bought supermarket blueberries in anything other than those clear clam shells that, in fact, aren’t very recyclable but do deliver a healthy and fresh product?)

But Sweeting, the former Moody president, argued that the church is God’s “living, small-scale demonstration of the world as it should be.” He felt that Christians did not have to be alarmist because “our confidence is in the Lord,” and rather than try to solve every problem, we should seek “God’s help to be examples to the world.”

Confidence in God will be as necessary for any changes we make today as it was for the Israelites during the Exodus from Egypt. This is something Evangelical Environmental Network president Mitchell Hescox knows, having come from a family of Pennsylvania coal miners. People of faith understand that climate change is real and dangerous, he says. But he adds in his book with meteorologist Paul Douglas: “We know how life was in Egypt, but we’re scared of the future going into the Promised Land.”

Is it possible that the very process of choosing to live more simply could free us, through acts of humility, to lay hold of something better than ourselves? To paraphrase Paul in his letter to the Philippians, we must not look to our own interests but instead suffer the loss of things in exchange for the knowledge of Christ.

Slaves to one another, not to our stuff

When the prophet Isaiah foretold the breakup of Israel and Judea, he referenced their abundant wealth and even their transportation, whose “land is full of silver and gold,” where “there is no end to their treasures,” and where “there is no end to their chariots” (Isa. 2:7–8).

Writers paint similar pictures of American society. In 1996, environmental writer Bill McKibben wrote a Christianity Today cover story subtitled “Why spending less and turning off TV should be part of the church’s mission to the world.” McKibben proclaimed that our consumer ethos was like “a tree whose canopy spreads so wide that it blots out the sun, that it blots out the quiet word of God. . . . We are led daily, hourly, into temptation.”

Five years later, John de Graaf and his co-authors reported in their book, Affluenza: The All-Consuming Epidemic, that four million pounds of raw material such as mined metals and oil are necessary to provide for one average American family’s annual consumption. Americans spend more on trash bags in a year than 90 of the world’s 210 countries spend for everything.

While consumption is a major component of the hallowed gross domestic product by which many politicians and economists measure goodness, it seems undeniable that Americans, including Christians, will eventually have to learn to live with less. We will have to treat our gifts from God—whether natural resources, material well-being, or personal and societal freedoms—with reverence rather than abandon.

We may need to turn again to Paul. When he wrote to the Galatians and made his case for the fruit of the Spirit, he set up his argument just a few sentences earlier with an admonition that surely was not written with our modern levels of material consumption in mind but whose application rings eerily prescient in our day:

You, my brothers and sisters, were called to be free. But do not use your freedom to indulge the flesh; rather, serve one another humbly in love. For the entire law is fulfilled in keeping this one command: “Love your neighbor as yourself.” If you bite and devour each other, watch out or you will be destroyed by each other. (5:13–15)

Ken Baake is associate professor of English and of the Climate Center at Texas Tech University. He specializes in the rhetoric of scientific literature. Managing editor Andy Olsen contributed to this piece.

Have something to say about this topic? Let us know here.