In early spring, the coronavirus pandemic sent the global food supply chain into disarray. In US grocery stores, prices surged, and many items—not just toilet paper—simply disappeared from shelves.

At some fruit and vegetable farms across the country—particularly those that sell directly to consumers or stores—business remained strong or even improved. But other farms watched the market for their produce dry up overnight, forcing them to cut operations, pull acreage out of production, and endure the heartbreak of tilling harvest-ready crops into the ground.

At the base of this teetering agricultural system are migrant farm workers. Just under 10 percent of laborers come to the United States on H-2A visas, which allow them to work in agriculture for up to 10 months. The other 90 percent of seasonal farm workers live domestically and often earn minimum wage, patching together jobs in hospitality, restaurants, and a rotating schedule of crops. Nearly half are not authorized to work in the United States.

For many workers, the pandemic has made an already difficult living even more daunting. Growers and packing houses laid off workers. The virus moved quickly through some farms and buildings that house agricultural workers, many of whom don’t have health insurance.

CT met with pastors, farmers, field workers, and activists in California and North Carolina who were ministering to migrant farm workers before the pandemic and continue to do so today. In ministries of word, mercy, and justice, these Christians are approaching the complex challenges facing laborers in ways that are varied and, at times, even contradictory.

Word

San Joaquin Valley, California

The sun had not fully risen when Tom Rios sat down with the men in his morning Bible study. To accommodate the schedules of the workers who participate, the study convened at 5:30 a.m. Today, they were meeting in Rios’s backyard just outside of Kingsburg, California, nestled between fields and orchards along the banks of the Kings River.

They discussed Romans 1:16–17. Christ alone, Rios explained in Spanish, is sufficient to satisfy a just God. He is the only mediator between God and man.

“No hay otro,” Rios said. “No hay otro.”

José Macias nodded along. This truth changed his life, he said later. He works for an irrigation company, pumping water to the fruit orchards that fill California’s arid San Joaquin Valley. He works with other immigrants as well as second- and third-generation Mexican Americans, and for most of his life, he said, he found ways to judge them, to think of himself as better. His attitude was getting him in trouble at work and causing conflict with his kids and wife.

After being humbled by the gospel, he said in Spanish, “I simply treat people with respect.”

Bible study wraps up promptly at 6:30 a.m. most days. The men have to get to work. Macias already had to take an hour off to attend. He won’t be penalized. The farmers who employ him, the Jacksons, want him at the Bible study.

Brian L. Frank

Brian L. FrankEvangelism and discipleship are built into the Jacksons’ business model. That’s why, in 2015, they hired Rios. Officially, he is the safety manager for Kingsburg Orchards, which grows apricots, plums, peaches, and other stone fruits. Rios has plenty of duties on that front, ensuring workers are trained on their equipment, informed of ergonomic ways to harvest, and following other protocols—all of which help the farm comply with federal regulations and attain various quality certifications.

But Rios’s presence there has a higher purpose: discipleship.

“I consider it one of our best investments—and investing in people—that we can share the gospel with our own employees,” Brent Jackson said.

Brent’s uncle, David Jackson, shares that sense of mission. In a video made for Texas grocer H-E-B, one of the family farm’s customers, he describes farming as the family’s calling. “As Christlike people, we were told to proclaim the gospel,” he told CT.

Rios delivers a weekly midday Bible lesson at one of the Kingsburg Orchards pack houses, with multistory conveyor belts zigging and zagging in the background, ferrying boxes of plums. Lunchtime changes every day, depending on when the workers start harvesting.

Rios limits his message to around 12 minutes, he said, so they can use the rest of their short lunch break to relax and socialize. During the pandemic, it’s one of the only points in the day when workers can take their masks off.

Most, though not all, of the pack house workers are women. A growing number of field workers in the US are women as well. Around 30–40 percent of the workers are women at Family Tree Farms, a nearby orchard owned by David Jackson.

At Kingsburg Orchards, Aida Villaseñor prefers the fields. The pack houses are too quiet, she said. If workers talk on the line, “the supervisor gets mad.”

She loves picking fruit with the other workers, who chat and sing together as they move between trees. The more casual environment makes it worth it to her to be out in the fields, where temperatures regularly top 100 degrees in the summer.

Brian L. Frank

Brian L. FrankRios interacts with field workers as well. In addition to his regular mingling and safety checks, he preached a gospel message at the end-of-harvest barbecue hosted by Brent Jackson.

One morning in late July, Jackson and his management team—many of them family—lit a huge circular grill, fashioned in their welding shop under the awning of an equipment barn. Workers gathered in the shade, facing a buffet spread atop a flatbed trailer. Jackson stood in front of the trailer as he shared, in Spanish, his appreciation for their hard work over the course of the season. The foreman said a few words of gratitude, and then Rios stepped to the front to share the gospel. Workers were welcome to take paperback Bibles from a large stack at the end of the buffet line.

Villaseñor took one before hopping in the food line. She said she appreciated the message, and the boss’s words of gratitude. “It’s good for everyone to hear,” she said.

Rios said it’s difficult to tell which of the gospel seeds will bear fruit.

Brent Jackson knows that not every person who hears the Word of God will respond, but some will, he said. For those, he’s not just after casual assent: He wants to see changed lives under the lordship of Christ.

“Whenever we think of ourselves as the king, we get into trouble,” he said, “Whenever we serve the King Jesus, then he leads us in peaceful ways, and he leads us out of our bondage to whatever addiction or slavery we’re under.”

He disciples about 16 of his employees directly and has built discipleship into the management structure of the company. He can’t know all 4,000 of his employees, he said, so he has to hire people who will form relationships across the entire company. His mission, he said, is to build the kingdom of God. And to him, that means evangelism.

Workers at Kingsburg make roughly $15 an hour. Brent Jackson knows that in California—even in the San Joaquin Valley, and even with the commissions earned by some workers—they are still considered financially poor. (California’s minimum wage for large employers is $13 an hour and will increase to $14 in 2021.)

The Jacksons chafe at talk of efforts to mandate higher farm wages. It makes some stone fruit fields unsustainable, they explained, because consumers won’t pay enough for peaches or nectarines to support better worker pay. When labor costs climb too high, some farmers convert fields to almonds or other crops that require less manpower.

Instead, David Jackson emphasizes the dignity of work and the wages received for it. “Americans don’t believe it’s good out there” in the fields, he said, “but it’s good out there. It’s honorable.”

Those who have been helped by the Jacksons and the church they attend with Rios, Grace Church of the Valley in Kingsburg, are quick to tell stories of schedule flexibility, financial assistance, and other forms of support as needed.

But David Jackson said that he cannot provide those benefits preemptively or at scale. He doesn’t have the profit margin. His workers often have to rely on charity—his or others. That’s part of the calling of the church, he explained, quoting Matthew 26:11, in which Jesus said, “The poor you will always have with you.”

For some workers, the fields of Family Tree Farms serve as a stepping stone to higher-wage jobs, either within his operation or in other industries. But he can’t guarantee that for everyone. He reasons that he can, however, give them Jesus. “The real riches are spiritual.”

Mercy

Santa Barbara and San Luis Obispo Counties, California

In the span of an hour, four different people showed up at pastor Mario Garcia’s front door in Oceano, California. Visitors hastily donned their protective masks upon entering the house as his wife, Maria, and their teenage daughter gave instructions in English and Spanish. The visitors then grabbed some supplies and went on their way. It was delivery day, Mario explained, when the family coordinated volunteers to distribute boxes of food to pickup sites around the community.

“If I want to serve these people, I need to be able to provide something for them,” he said.

If it weren’t for COVID-19, he explained, things would be much busier. His church usually hosts soccer clinics and yard sales, but most of those activities slowed as California’s stay-at-home orders waxed and waned over the summer.

Despite some adjustments, Garcia’s ministry was not as dramatically affected as others. Funded by Grace Bible Church in Arroyo Grande, his Grace Hispana ministry has decentralized since 2019. It doesn’t meet in the church’s spacious building overlooking the Pacific Ocean. It doesn’t meet in large groups at all.

Instead, Garcia mixes and mingles in the communities on the other side of Highway 101: Grover Beach and Oceano, where the population is majority Latino and the average home prices are $250,000-$300,000 less than in Arroyo Grande.

“I don’t want to be a pastor of a church,” Garcia said. “I want to be a pastor in the community.”

It took some time to find a model that worked in this particular community.

When Garcia came up to interview for a job as a Spanish-language pastor in San Luis Obispo County 18 years ago, the pastor from Grace Bible Church toured him around the expansive fields of Santa Maria, where huge agricultural operations like Bonipak and Teixeira Farms are located. These were the people they wanted to reach, the pastor told him.

It seemed like a natural fit. Garcia had worked strawberry fields in Southern California for years after coming to the United States from Mexico when he was 22.

However, the ensuing years would be a constant lesson in the difference between the culture of his birth and the culture of his second birth. He understood Mexican culture. He understood the fields. But the way he had learned to “do church” in Southern California was not working.

Garcia quickly figured out how to connect with the community—the garage sales and soccer camps were early successes—but getting people to church was more difficult.

Among the broadly Hispanic workforce are members of various Mexican immigrant communities, tightly knit groups from different Mexican states. They work long hours; many field workers don’t get Sundays off. Two groups, those from Michoacán and Guanajuato, Garcia said, were particularly suspicious of him. When he first arrived in 2001, a Catholic deacon told him, “You will feel the resistance.”

He did feel a resistance to evangelicalism, he said, which is seen by many as a white American expression of faith. Catholicism, for some of his neighbors, is as much about home as it is about heaven. When they are urged to trade it for something they found in America, Garcia explained, it feels like they are being asked to give up more than confession and transubstantiation. They’re being asked to give up being Mexican.

The connection he made had to start with service and culture. Yard sales were a huge social activity as well as a sort of mutual-aid endeavor in the neighborhoods, and kids’ soccer camps helped working parents pass on the sport many of them played growing up. Garcia also got involved in the schools and the community. He translated for neighbors who ended up in traffic court for driving without a license, which was more common before 2013, when California stopped requiring proof of legal presence to obtain a driver’s license.

“We found ways to connect with people so that we could build these relationships,” Garcia said.

Diane Martinez’s church connected her to a different kind of mercy ministry with farm workers: immigration law.

She didn’t see herself in immigration advocacy at first. “God just surrounded me with the immigrant population,” Martinez said. Her neighborhood in Santa Barbara, Westside, is home to more low-income families than the rest of the famously quaint seaside city. Many do not speak English or are students at Santa Barbara City College, where she was teaching.

Martinez’s church, Shoreline Community Church, had been trying to find a ministry that would meet practical needs of people in the community. (“You always know when it’s your idea and not God’s, because it doesn’t work,” she said.) Finally, her pastor sent Martinez and another representative to an immigration conference in San Diego.

Brian L. Frank

Brian L. FrankThat was it, the ministry they had been looking for. “I came out of there just knowing,” Martinez said. “The Holy Spirit lit it up.”

She spent the next two years studying immigration law and earning the necessary certifications to open a legal clinic. Her church connected with Immigrant Hope, a national nonprofit operating legal clinics in eight states. In May 2014, she opened the Santa Barbara chapter, which runs independently of but is housed at Shoreline.

To be truly effective, the clinic could not just wait for clients to come—most work long hours and use city busing for transportation. Martinez started going into immigrant communities in the surrounding county, which eventually led her to New Cuyama, a farming area two hours east on the other side of Los Padres National Forest. Immigrant Hope now works through the community center there to help farm workers and their families apply for legal permanent residency, naturalization, and, until recently, for Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals status, which allows some immigrants who are brought into the US as children to remain and work in the country legally (the Trump administration has tried to end this program).

About half the people the clinic meets in consultation have a way forward toward legal status. That percentage is high, Martinez said, because those who know they have no options don’t usually schedule a meeting to confirm it.

“There’s many people out there that, because of the way they came [into the US], they have no pathway to legal permanent residency,” Martinez said. However, if one person in a family can become naturalized, pathways sometimes open up for others. For parents and children of a naturalized citizen, the process is short compared to that for brothers and sisters, which can be 20 years.

Beyond offering legal services, Immigrant Hope helps clients study for citizenship tests, learn English, and apply for waivers to the naturalization fee, which US Citizenship and Immigration Services recently raised by 80 percent to $1,160.

Brian L. Frank

Brian L. FrankThe clinic also forges relationships with medical clinics, libraries, schools, and public service departments. In Santa Barbara, the local Federal Emergency Management Agency representative worked with Immigrant Hope and the fire department to create the nation’s first Spanish-language Community Emergency Response Team, a volunteer disaster preparedness program.

Though they never require anyone to pray or sit through a gospel presentation to receive help, Immigrant Hope offers spiritual support to its clients as well. “Rarely do we have anybody turn us down for prayer,” Martinez said. Sometimes, clients are curious to hear more. “We get to tell them about a citizenship where applications are never denied.”

Martinez also feels called to another kind of outreach: church education. She tries to help evangelical churches see immigration as more than a social justice issue. It’s about God’s justice, she said. She respects their desire for lawfulness, but her expertise allows her to explain how immigration law has never been immutable or absolute. Policy and politics have dictated the interpretation of law for over 100 years, immigration lawyers explain, and the people most affected—prospective and undocumented immigrants—cannot vote and thus have very little say.

Justice

Dudley, North Carolina

For marginalized people to exert pressure on unjust systems, they must organize, explained union leader Baldemar Velasquez. And they must take good notes.

In his 53 years with the Farm Labor Organizing Committee (FLOC), Velasquez has become very good at documentation—taking the testimony of workers and translating that into campaigns to solve problems.

His relationship with the growers is “very respectful,” Velasquez said. “That’s the way it ought to be.” If a worker complains about wages being docked or breaks not being given as usual, FLOC tries to present the claim professionally, as a human resources issue, not accusing the farmer of ill intent or asking for special favors.

Resolving things “like a family” just doesn’t work, he said, because farmers and laborers don’t come to the table as equal members of the family. “They’re like family until (workers) speak up for their rights,” said Velasquez. “Then you have a bad family feud.”

In Washington, Roy Farms’s chief operating officer John Erb believes labor relations need to be part of an overall healing in the agriculture industry. “Thy kingdom come, thy will be done, on earth as it is in heaven” is why, Erb said, he worked as a consultant helping farmers invest in their workers and their communities before joining Roy Farms, a Yakima Valley fruit and hops producer that markets its ethical and sustainable practices. Erb believes that biblical stewardship of the earth and human relationships can bring some measure of peace and justice to a broken world.

Empowering workers is key, he said. And sometimes that means welcoming labor unions.

Erb said he has often advised growers that “if (workers) want representation, you do not get in the way of that.”

Not that Erb believes unions are the best way to ensure workers are treated well. Standards and enforcement are better safeguards, he said, and grocery retailers and food service buyers can also help through their purchasing choices. “It really comes down to leadership across the supply chain,” Erb said, “starting with a commitment to workers from the buyers.”

Velasquez has similar interests. He views labor organization as a form of reconciliation. The negotiating process can feel litigious and formal at first, as farmers’ eyes are opened to how their workers feel about how they are treated. It is often emotional, and the formal process keeps everyone accountable.

But after about two years of working with unionized labor, Velasquez said, he sees a shift in how growers see their employees. They aren’t surprised when workers want improvements to their working conditions. Migrant farm workers become like any other employees who have expectations.

“That’s when we can start solving things around the kitchen table with a cup of coffee,” Velasquez said. Once the respect is there.

Brian L. Frank

Brian L. FrankVelasquez is not looking to punish anyone. Not after a relationship with Jesus changed his life. As young man, he felt wounded by the abuses he had experienced in the fields of the Texas and Midwest farms where he worked with his family from the age of five. Velasquez first approached organizing with an “attitude of getting even,” he said. “When I came to know the Lord, that sort of flipped upside down. It was no longer about revenge; it was about reconciliation. Reconciliation is harder than being angry and getting even.”

In the mid-1970s and ’80s, Velasquez led the FLOC through a nearly eight-year boycott of Campbell’s soup. That, too, he saw as an act of reconciliation, and a model for bringing small farmers and laborers together for their mutual survival.

“Economically, we’re in the same boat,” Velasquez said. Like Erb, when he looks at a farm labor issue, he looks at the entire supply chain to find the source of the injustice. When it comes to wages, problems do not usually begin with the farmer—they begin with food prices at the retailer.

Farm workers in Ohio wanted to protest wages that they felt were unfair, but Velasquez knew the farmers weren’t getting enough from Campbell Soup Company to increase the wages. If the workers went on strike, farmers could grow simply grow corn or soybeans instead—cash crops that demand little labor.

So the workers went to Campbell, which had the money to pay farmers more, and worked to guarantee the farmers would pass those profits on to people picking in the fields. It was an arduous process that involved, among other feats, a 600-mile demonstration march from Ohio to New Jersey. But in the end, farmers and workers got higher pay, and Campbell also offered health care benefits to the farm workers.

Velasquez knows that farmers and their customers in the food and grocery industry don’t like the high-profile “shaking and moving.” But sometimes, he said, nothing else works. “You’ve got to get people’s attention.”

Brian L. Frank

Brian L. FrankBack on the West Coast, John Erb is trying to get someone else’s attention: the consumer. “The market isn’t going to meet a demand that doesn’t exist,” he said. Unless people recognize the value of paying a bit more to help farms care for their workers, their land, and their communities, Erb said, squeezing pennies out of the supply chain will be the only way for small and even midsize farms to survive.

Erb has worked with farmers and their retail clients to raise awareness of efforts like fair trade and the Equitable Food Initiative, which certify foods that were grown and harvested ethically. Getting such certifications can help farmers command a higher price for their goods from socially conscious supermarket customers.

Advocates for migrant workers know that higher wages alone will not resolve every challenge facing low-income Latino families and immigrants.

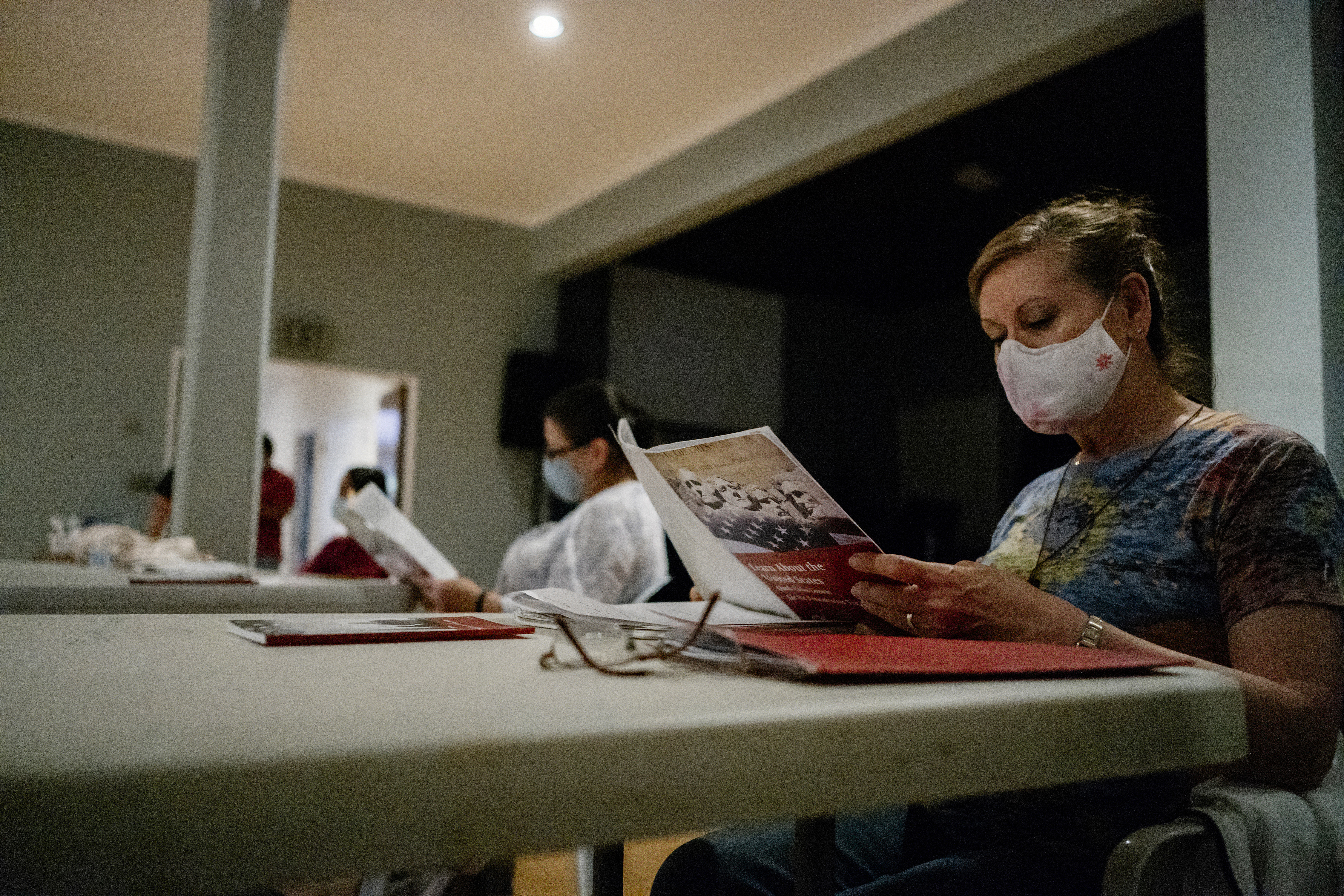

At a meeting in July, Velasquez and the organizing team in Dudley met at the FLOC North Carolina headquarters. In 2006, FLOC built a large metal building that could serve as a meeting place, distribution center, and hurricane shelter. It’s big enough that the group could stay socially distanced while eight organizers, wearing masks, sat at their laptops. Another 10 joined on Zoom. They discussed the need for bilingual education as well as concerns about interactions with the police. FLOC gets involved wherever their members need protection; they know both well-being and injustice extend beyond the farm.

During COVID-19, the FLOC headquarters has also transitioned into a hub for public health and safety supplies. Pallets are piled high with boxes of bottled bleach and disinfectant. Washing machines line the back wall.

“We’ve been using the center as a place to distribute material to prevent the spread of COVID,” Velasquez said. He referenced Martin Luther, who famously agreed to obey the law during a flare-up of the Black Death but was willing to risk his health in ministry. “We know we’re taking risks. But when you’re a people of the people…when it comes to loving, you don’t count the price.”

Bekah McNeel is a Texas-based reporter who covers immigration and education.