The 10-minute commute from home to my office at church has always had risks. Driving carries its own inherent danger. Then I have to find parking (sometimes in the dark, and often as the first car there); navigate the security alarm; and if a male coworker arrives, consider the risk of being a woman alone in a building with a man.

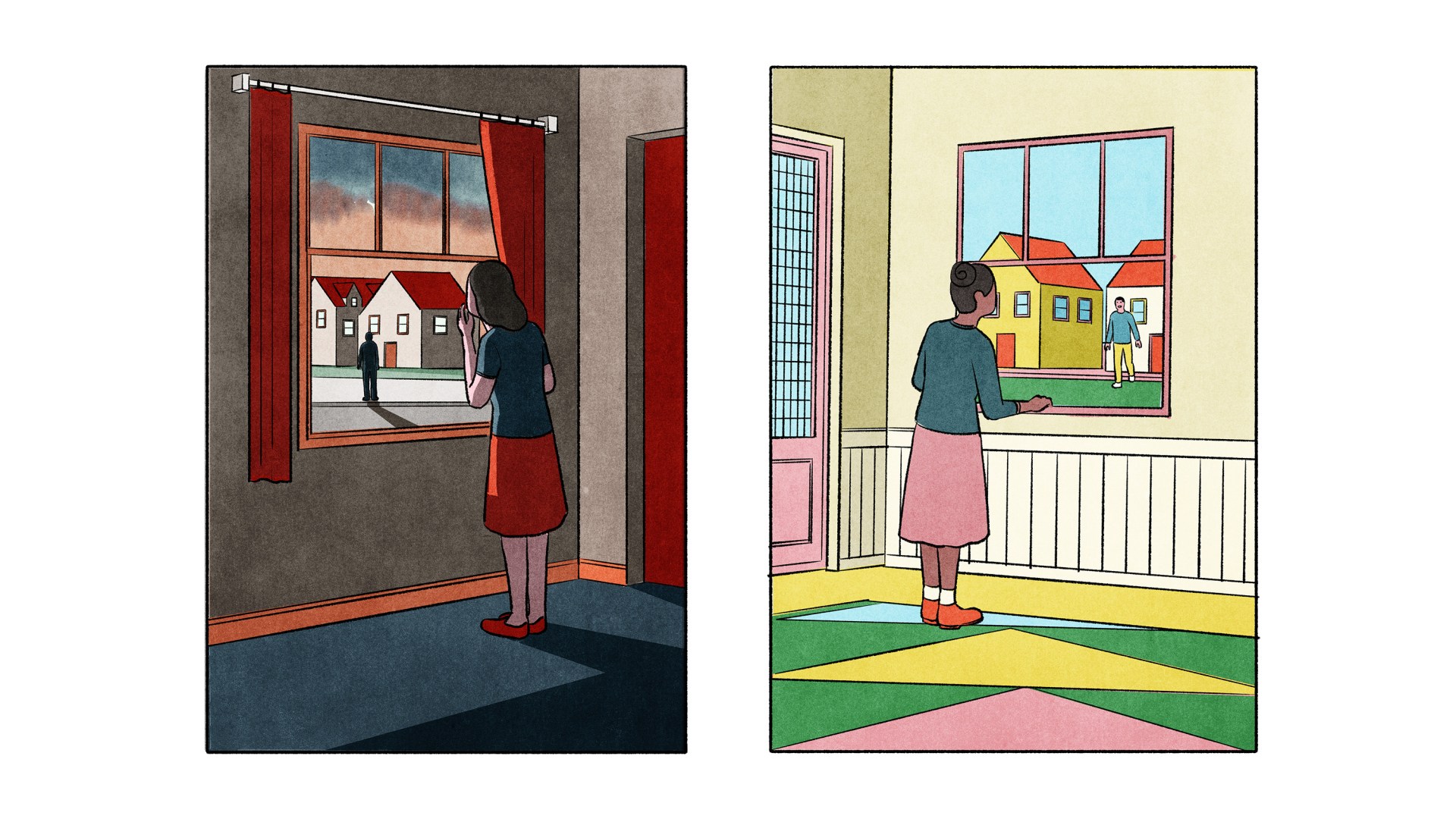

Twenty years ago, I found driving somewhat scary and walking across the parking lot alone terrifying; but being in the office with a Christian brother did not worry me one bit. Today, however, while driving remains something I’m careful about, I hardly think about getting out of my car once parked, and I’m considerably more aware of the male-female office dynamics. What caused the shift?

Approximately 10,000 miles.

In many ways, moving from South Africa to the US decreased my fear levels because the actual risks were lower. Driving in South Africa is statistically more dangerous than it is in the United States. Walking alone as a woman is less dangerous in Northern California (South Africa regularly claims the highest rape rate in the world). Over time, my fear lessened, recalibrating to the new risk levels.

But my perceived concerns about being alone with a male coworker increased when we moved to the US, even though I had no reason to think the risk of impropriety had actually changed. I found myself in a local church culture far more anxious about male-female interaction and needed to adapt my awareness accordingly.

Where we live influences both what we fear and how much we fear it. Of course, the size of our fears is affected by the size of the risk; we are more afraid of shark bites than jellyfish stings. But our fears are shaped even more by our perception of the size of the risk. The film Jaws conditioned an entire generation to be wary of shark fins at every beach, even though there are an average of 71 shark attacks per year compared to an annual average of 150 million jellyfish stings.

The COVID-19 debates over appropriate levels of caution are fraught with tensions between perception and reality: Boosted Americans are more worried about contracting the disease than their unvaccinated fellow citizens, despite their lower risk of being seriously affected. As it turns out, where we live makes a significant impact on our perception of threats. Studies have found that fear of the virus varied from region to region.

These differences in how we assess risk affect how we treat others. Much of learning to listen to and love our neighbors well has to do with how we respond to their fears, whether we share them or not. But what if we, judging others by our own personal fear levels, believe they’re much-afraid of little things or that their fears are unfounded? Or what if we believe others are being blasé about things we feel are real dangers?

The geography of fear

We need to ask where our fears come from and how much our location plays into them. We know our own personal experiences shape our fears for good and for bad: Our body keeps a score for both healthy and traumatic experiences. Adverse childhood experiences, mental health issues, and personality differences (neuroticism, for example) play significant roles in forming our fears.

But our locale does, too. In a multinational survey from the early 2000s, National Bureau of Economic Research’s Daniel Treisman found that, whether the object of fear was global like nuclear war or personal like the fear of serious medical errors, survey respondents in Portugal were two to three times more likely than those in the Netherlands to say they were afraid.

And while more than 80 percent of Greeks reported worrying about weapons, genetically modified foods, and new viruses, fewer than 50 percent of Finns said the same. Treisman concludes that “of course, some countries are more dangerous than others. Their inhabitants might be more afraid simply because they have more to be afraid of.”

Yet, he argues, this only explains part of the variation. While researchers could compare people’s fear levels of some dangers to their objective risk, the results showed “the correlations between these (were) often weak, non-existent, or even negative.” In other words, some communities were far more afraid of certain things, even when there was no greater risk of those things happening.

Another example of cultural differences: Each year, the Chapman Survey of American Fears asks a random sample of respondents across the US about 95 different fears ranging from the environment and natural disasters to the government and COVID-19. The most recent Chapman survey revealed that for the sixth consecutive year, Americans’ number one fear (80%) was corrupt government officials.

My South African brain sputtered when I read this report. I studied political philosophy and law at university, and the American democratic system with its checks and balances seemed to be the one that should engender the least fear, from where I was sitting. I called my Nigerian coworker and asked what he made of it.

“I’m stupefied,” he answered. “Corrupt government is a real issue of concern in my home country, but here? Why are so many people afraid?”

Formed by fear

Certainly, fear wells up from within us. But it seeps in from around us, too. Where we are in the world does more than teach us particular ways of living and thinking; it also shapes us in ways of loving and fearing.

Reading reports like these make me wonder: If I lived in a different country, or on a different coast, or in a different state, how would that affect me? How might I process the disasters, diseases, and dreads of this world differently? And how, in turn, would that change the way I related to others around me with compassion?

Catherine McNiel argues in Fearing Bravely: Risking Love for our Neighbors, Strangers, and Enemies that we’ve underestimated how much our immediate culture—whether the physical neighborhood we live in or the digital community we live in virtually—impacts our fears. We’ve been discipled to fear, says McNiel. A disciple is a learner, and we learn a great deal from the stories and emotions of those around us.

We are supposed to disciple people to love God and love our neighbor, but unless we address the ways our environments have taught us to fear “the other,” our attempts to love that neighbor will stumble.

Jesus calls us to enter this world, love our neighbors, take care of strangers, and pray for our enemies, too.

We are malleable creatures. We like to think that we read news and stories to gather information, acquiring facts to impartially assess and then accept or reject. What we underestimate is how this information is also formation: kindling our affection for some things and stoking our fears about others. Facts come with calls to action and appeals to our affection, and those have a local flavor.

As James K. A. Smith said in a CT interview, our habits form us, and this includes our reading habits, our media consumption, and the regular conversation partners with whom we share our day-to-day concerns.

Word of mouth is the quickest way to get out good news (consider God’s wisdom in how he sends salvation to the world), but it is also the quickest way to introduce and escalate worry. I hadn’t spent a minute of my life worrying about a proposed new school curriculum, for example, until I heard fellow parents whispering about it in the school pickup line.

For weeks, it was a topic over multiple dinners and in the local parent Facebook groups. Conversation by conversation and comment by comment, as we traded anecdotes and analyses, we stoked fear too.

There’s a name for this phenomenon of wildfire-like fear spreading: social cascades. Cass Sunstein, Harvard law professor, behavioral economist, and author of Laws of Fear, explains: “Through social cascades, people pay attention to the fear expressed by others, in a way that can lead to the rapid transmission of a belief, even if false, that a risk is quite serious. … Fear … can be contagious, and cascades help explain why.”

We are also susceptible to group polarization, writes Sunstein, so much so that groups are often more fearful than individuals. We might be a little afraid—or not afraid—of something on our own, but we can find ourselves deep in moral panic when we get together and pool our fears.

Christians, however, are called to speak to God in secret, naming our concerns before him in prayer (Matt. 6:5–8). But we cannot confess what we have not named, and the difficulty of dealing with our fears is that they are often subliminal. We might not even know what we’re really afraid of underneath it all. And even if we are, what then can we do about it?

Again and again, the Bible tells us not to fear (Deut. 31:6; Isa. 41:10; Luke 12:32). “For God gave us a spirit not of fear but of power and love and self-control,” wrote the apostle Paul in 2 Timothy 1:7 (ESV). “I will fear no evil, for you are with me,” writes David in Psalm 23:4. Scripture is clear that people of faith are both commanded and empowered to root out fear.

But fear is a nuanced topic. The Bible doesn’t say all fear is wrong; rather, it cautions us not to fear wrongly.

Some fear is sinful, but the fear of the Lord is commended as wisdom. “Sinful fear causes us to spurn God and transfer our affections, hopes, and fears elsewhere. Health, wealth, relationships, and reputation are just a few of the things that take on a ‘divine ultimacy,’” says Michael Reeves, author of Rejoice and Tremble: The Surprising Good News of the Fear of the Lord.

Jesus himself warned that we might be fearing wrongly—and as a result, prioritizing wrongly (Matt. 10:28)—and he invites us not to get stuck in our fears, which are often far more informed by the people around us than by the truth. We might be in danger of fearing the wrong things altogether, or we might fear the right things but in the wrong amount.

But as any person who’s ever struggled with anxiety knows, having someone say, “Don’t worry” doesn’t magically eliminate fear. Spiritual growth cannot come from emotional gaslighting; denying or rebuking our fears doesn’t eradicate them. So how, then, are we to learn not to fear the wrong things?

Faced with the task of comforting a frightened congregation in the midst of political turmoil, German pastor Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s answer was: Preach! Or at least, listen to good preaching.

“Fear secretly gnaws and eats away at all the ties that bind a person to God and to others” until “the individual sinks back into himself or herself, helpless and despairing,” Bonhoeffer said.

Regular, faithful teaching directed at the character and power of God, the promise of Jesus who has overcome the world, and the presence of the Holy Spirit who is with us through it all speaks a powerful message to anchor us in hope when the storms of life seek to toss us around.

We, the united church, can encourage one another in hope (Heb. 10:23), and this does help us to face our fears. But we also have work to do on a much smaller scale, and realizing how much our location impacts our formation can help us disciple people away from fear and toward love.

Praxis and proximity

Growth can come from learning to be curious about why we think the way we do, and being willing to doubt it, Adam Grant argues in his best-selling book Think Again: The Power of Knowing What You Don’t Know. Learning to be curious—and even skeptical—about our fears is a significant first step in our being able to deal with them.

This isn’t intuitive. I usually think my fears are reasonable and rational; otherwise I wouldn’t have them. But moving between countries and visiting different church groups has revealed that often I am much more or much less afraid of a thing than the believers with whom I’m worshiping. This in turn has become an invitation to humbly and prayerfully evaluate what and why I love and fear.

The spiritual practice of discerning our desires before God can include questions to interrogate our fears. Ignatius of Loyola’s examen offers one such tool for introspection, inviting us to discern where we experience consolation and where we experience desolation. Fear would be a firm contributor to the latter.

Writer Brendan McManus explains in a blog post how learning to “be aware of your feelings, and then use your head” can be a simple but useful formula for a spiritually sophisticated approach: “The first step is to reflect on the experience or decision and ask, ‘How do I feel about this?’, whereas the second part looks forward, asking, ‘Where is this bringing me?’ and, ‘What is the likely outcome or fruit?’ Exploring these questions, we can tune in more to what God wants, be more attuned instruments for God in the world, and, ultimately, make better decisions.”

We can let our guards down, even if we disagree on letting our masks down.

Acknowledging that my fears have been culturally informed and formed by where I live—and that those fears have brought me to certain conclusions and will, if unaddressed, have a certain outcome or fruit—invites me to hold them loosely and examine them closely, offering myself both grace for the (real) concerns I feel and room to grow as I learn from new perspectives.

When looking at the fear map of my own heart, zooming out to hear stories from the broader church helps me to recalibrate my concerns, so that I can then invite God to “test me and know my anxious thoughts. See if there is any offensive way in me, and lead me in the way everlasting” (Ps. 139:23–24).

What’s more, we may need to physically close the gaps. If geography—that is to say, physical distance between communities—plays a role in curating our fears, then we should also consider how shrinking that distance can help us cure them. Tyler Merritt, author of I Take My Coffee Black: Reflections on Tupac, Musical Theater, Faith, and Being Black in America, argues for proximity as a tool to address racial suspicions. “Distance breeds suspicion. But proximity breeds empathy,” he writes, a concept he attributes to pastor and author Bryan Loritts. “And with empathy, humanity has a fighting chance.”

In 1 Corinthians 10, the apostle Paul addressed an anxious and fractured nascent Corinthian church that was facing concerns that hadn’t come up in Jerusalem. Some new Corinthian believers came from a pagan background where meat was sacrificed to idols in worship. When eating at an unbeliever’s house, they feared they might be eating something that had been part of a demonic tradition.

Others took a broader view: “The earth is the Lord’s, and everything in it” (v. 26), so they could participate in meals without fear. How were these believers to eat and worship together if they had such different assessments of the risks on the menu?

Paul’s response provides a master class in how we might address our own fears, as well as those of others, with grace and truth. First, he acknowledged the reality of their concerns: Yes, for many, this practice is not just about food, but about participation in a dangerous and demonic realm (vv. 20–22). Then, he offered Scriptural context to help them wrestle with the specific questions arising out of their cultural background: Since the earth is the Lord’s, whatever is sold in a meat market can be eaten without raising concerns about conscience (vv. 23–26).

But even though Paul, coming from where he did, did not share their concerns, he called others to make allowances for them in love. Respect others’ consciences, he counseled (vv. 27–33). Scripture calls for us to be gentle and respectful where people are afraid, leaving room for their fears, even if we do not share them.

Taking the risk to love

Social scientists have shown that negative partisanship—our animosity toward and fear of the “other” side—drives our political behavior far more than our actual confidence in the policies and philosophies of “our” side.

“How we feel matters much more than what we think,” Ezra Klein observed in his book Why We’re Polarized. We are primarily feelings-based social creatures, and in elections, for example, Klein says, “The feelings that matter most are often our feelings about the other side.”

That means the Christian who wants to work out their faith in the public square needs to do more than just think about things biblically before choosing. We need to be able to acknowledge and then address how we feel about things before choosing. Who and what do we fear? Who and what do we love?

And just as we know it is wise to identify the sources for our facts when thinking, wisdom invites us to consider the sources and motivators for our feelings.

Zooming out to hear stories from the broader church helps me to recalibrate my concerns.

Deep-seated and localized fears about food sacrificed to idols were keeping the Corinthians from being able to love their neighbors and share table fellowship with them. In the 21st century, deep-seated fears continue to keep us too from loving our neighbors well.

I imagine Paul might have very similar words to write to believers in my community, where the fear of COVID-19 is high (and mask-wearing very common) as we interact with some believers just 150 miles south of us, in a community where fear of adverse vaccine reactions significantly outweighs the fear of COVID-19 (and mask-wearing is low).

How might he teach us to acknowledge the concerns of our fellow believers, rather than dismiss them, and call us to make room for one another in love so we can enjoy table fellowship and partner in kingdom work? We can let our guards down, even if we disagree on letting our masks down.

Just as my American brothers and sisters have helped me to name, contextualize, and process some of the fears I acquired in South Africa, perhaps my Nigerian coworker and I can help our American church deal with some of its local fears. We can’t do anything to lower the actual risk of corrupt government officials, but perhaps we could mitigate some of the fear that 80 percent of Americans hold by sharing our stories of how we learned to trust God when we lived in countries with less stable governments.

Jesus calls us to enter this world, love our neighbors, take care of strangers, and pray for our enemies, too. To do so and risk love, as Catherine McNiel writes, will require us to journey through our fears, naming them before we can hope to tame them. But before we can name them, we might need to unfold the map of our lives and begin humbly sticking pins in the places where our fears have formed.

Bronwyn Lea is pastor of discipleship and women at First Baptist Church of Davis and author of Beyond Awkward Side Hugs: Living as Christian Brothers and Sisters in a Sex-Crazed World.