In this Close Reading series, biblical scholars reflect on a passage in their area of expertise that has been formational in their own discipleship and continues to speak to them today.

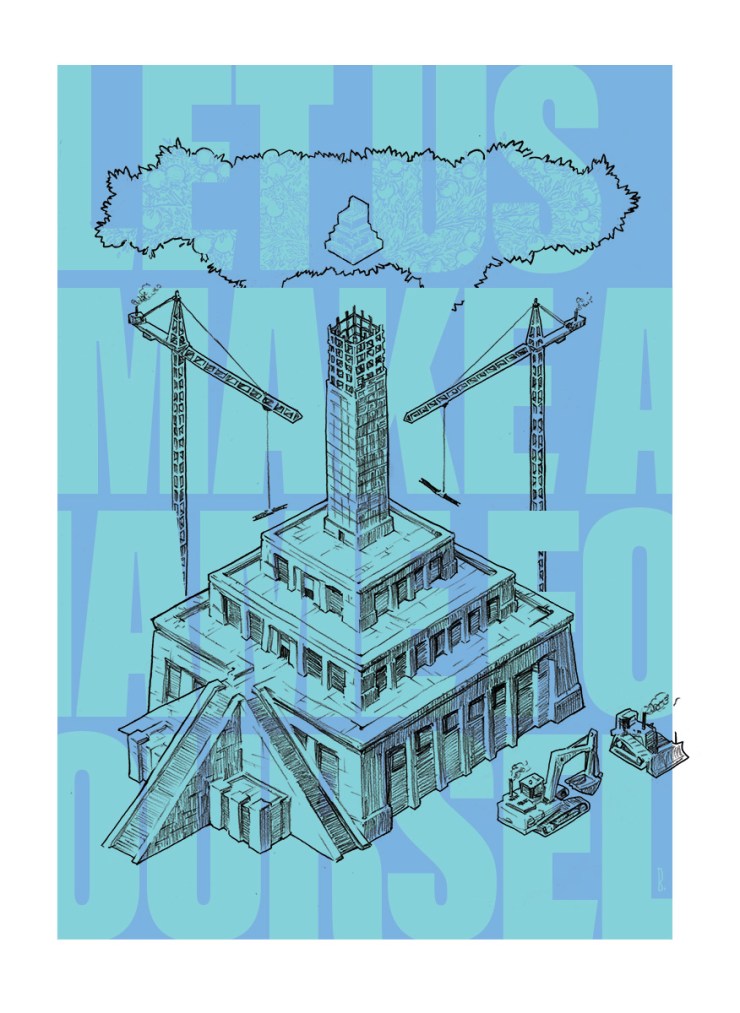

As I was growing up in church, the account of the Tower of Babel (Gen. 11:1–9) always aroused my curiosity. An artist’s rendition was among the few pictures in my Bible, and I spent many a sermon pondering it. The picture was colorful and vibrant, depicting a crowded and lively scene of human industry—smoke arising from countless kilns, oxen and men carrying heavy loads of brick, and workers using scaffolding and ropes to build a structure many stories high.

Years later, in my doctoral work, I decided to do my dissertation on this passage that thrived in popular imagination but was underserved in academic treatments. It is an amazing story—pivotal, yet often misunderstood. It is one of those stories that assumes a significant amount of cultural knowledge on the part of the reader, without which we intuitively impose our modern assumptions that can lead to skewed interpretation.

Today, and for centuries in the past, the common interpretation of this passage has been that the builders were attempting to storm the heavens, not unlike the Titans of Greek mythology, with any variety of intentions depending on the imagination of the interpreter. They were judged guilty of the gross sin of pride and, in some readings, of refusing to fill the earth, thus disobeying the command of Genesis 1:28. The inevitable lesson warns against the dangers of overweening pride, the hubris of ambition, and the folly of disobedience.

To be sure, humans are guilty of such wayward behaviors, but in this interpretation, the tower is reduced to a metaphor of rebellion and overreaching. I felt that something important was missing.

I eventually came to the conclusion that such a reading, despite its long tenure in Christian and Jewish interpretation, doesn’t stand up when subjected to close scrutiny, including recent knowledge gleaned from ancient Mesopotamian texts. This story is about something more.

Both potential offenses of the builders—pride and disobedience—begin to look like shaky explanations when examined closely. Genesis 11:4 reads, “Come, let us build ourselves a city, with a tower that reaches to the heavens, so that we may make a name for ourselves; otherwise we will be scattered over the face of the whole earth.”

People “make a name” for themselves through anything that would cause them to be remembered in future generations. Making a name is a phrase that speaks of honor and admirable reputation. In the Old Testament, it is used most often to refer to God making a name for himself—a great name that enhances his reputation (see Isa. 63:14; Neh. 9:10). On a few occasions, it refers to God making a name for someone (like Abram in Gen. 12:2 or David in 2 Sam. 7:9 and 1 Chron. 17:8). It is always positive.

Illustration by Jared Boggess

Illustration by Jared BoggessGenesis 11 is the only time in Scripture where people are making a name for themselves, but that does not mean it is inherently an offensive act. When we add information we find in other ancient Near Eastern texts (such as The Epic of Gilgamesh and The Epic of Etana), we learn that wanting to make a name for oneself is an honorable endeavor, characterized by good deeds and great accomplishments. The most common way that people made a name for themselves in the ancient world was by having children; your descendants were the ones who would remember you when you were gone. We have no evidence to substantiate the idea that “making a name” was inherently a bad thing in the ancient world—though in today’s culture we may be inclined to think of it as egotistical. In the ancient world it was like having a legacy.

When we turn our attention to their desire not to scatter, again we find little evidence of offense. Genesis 1:28 is explicitly a blessing, not a command to scatter that the builders later disobey. A blessing cannot be disobeyed because it carries no obligation. It is true that, grammatically, the verse is an imperative, but in Hebrew, imperatives have many functions besides command. In this verse, the filling of the earth is a result clause that indicates unlimited permission to be fruitful and multiply.

It is true that in Genesis 11, the people do not want to scatter—but that is not the same as not wanting to fill the earth. They are family, and families resist scattering. We see the same reluctance in the story of Abram and Lot (Gen. 13). In Genesis 11, reluctance to scatter is what motivates them to look for a solution, which is logically found in urbanization.

If wanting a legacy (making a name) and desire for community (reluctance to scatter) are normal and unobjectionable, we are then left to start from scratch to figure out what this passage is all about. If we limit the Tower of Babel account to a moral lesson about pride or disobedience, we miss out on the deeper understanding it offers us about God and our relationship with him. Starting with an investigation of the ancient world can provide new direction.

As I began my research, two important elements emerged to illuminate this passage of Scripture and revitalize its interpretation. The first is that almost all interpreters now recognize that towers such as the one described here are called ziggurats and—most importantly—now know why they were built.

Ziggurats were not built for people to ascend to heaven but rather for the god to descend from heaven.

In ancient Near Eastern culture, ziggurats were an important part of a temple complex. They were built next to the temples and were considered sacred space reserved for the gods. They were not built for people to ascend to heaven but rather for the god to descend from heaven. The idea was that the tower provided a convenience by which the god could make a grand entrance into the temple where he would be worshiped.

Once we have that information, we cannot help but notice that at the very center of the account in Genesis 11, God comes down (v. 5)—yet he is not pleased. The people were not aiming to make a name for themselves due to pride; they likely believed that they were making a name for themselves by providing a means for God to come down and be worshiped. So what is the problem here? Why is God displeased? Furthermore, since we are not building ziggurats today, what would this passage mean to us now?

Here we need to factor in the other element that we have learned about ziggurats. The god was believed to come down and enter the temple to receive worship, and in the ancient Near East, worship consisted of rituals designed to meet the supposed needs of the gods. Babylonians, among others, believed that the gods had needs—food, housing, clothing, and so on—and that the gods had created people to meet those needs. That is all the gods cared about.

The religious practice in this system was not defined by faith or doctrine, by ethics or theology; it was essentially defined as the care and feeding of the gods. The result of this mentality was a codependence in a symbiotic relationship between gods and humans that was entirely transactional: People would take care of the gods, and the gods would protect the people and bring them prosperity. Success was to be found in finding favor with a god, and favor was found by meeting his needs—indeed, his every whim. Pampered deities made for flourishing cities.

This helps us see why the people in Genesis 11 believed that building the city with its tower would make a name for themselves. They would make a god beholden to them, they would flourish, and their fame would spread—they would be people favored by a god.

The problem was not that they wanted to make a name for themselves. The problem was that they were exploiting a relationship with God to do so. And that is something with which we might be able to identify. Constructing sacred spaces should be motivated by wanting to make God’s name great, not by wanting to make our name great. How many of our great endeavors in the church—our programs, our building projects, our far-reaching podcasts, our great crowds of people—are focused on our glory and success rather than God’s?

In my desire to be an attentive and faithful interpreter, I have learned that narratives in the Bible are not best read in isolation. The narrators link them together as they pursue their literary and theological purposes. The account of the Tower of Babel brings to conclusion a sequence of narratives in Genesis 1–11 and also provides the link to the very different sort of narratives that follow in the remainder of the book.

Genesis 1 establishes the presence of God at Creation, a point that is clarified in Exodus 20:8–11. When God rested on the seventh day, he did not simply cease (shabbat in Hebrew); rather, he took his seat on his throne (his “rest”; see Ps. 132:14). The Garden of Eden describes people dwelling in sacred space. We regularly lament that their access to God’s presence was cut off in Genesis 3.

What we may neglect to see is that in chapter 11, the builders are launching an initiative to reestablish God’s presence among them. Only after many years of study did I make the connection that, after God rejects their misguided and selfish initiative to realize his presence, the next chapter launches what stands as God’s counterinitiative: the covenant offered to Abram.

Remarkably for the ancient world, this covenant is not premised on the idea that God has needs. He offers the same sorts of benefits to Abram that gods offered in the ancient world—he offers to make Abram’s name great. But there is an incredible difference: This offer is not based on codependent transactionalism. The covenant offers a different way of being in relationship with God.

Though the narratives in Genesis 1–11 are often seen as “offense stories,” an alternative reading suggested by theologian J. Harvey Walton is that they represent inadequate strategies by which people attempt to bring order for themselves through means common in the ancient world. For example, being like God (Gen. 3), establishing a family (Gen. 2), developing civilization (Gen. 4), city-building, and exploiting the favor of God all prove inadequate for establishing lasting order. God had made humans in his image to work alongside of him in bringing his order. Yet humans decided they would rather be independent contractors bringing order for themselves.

Genesis 1–11 tracks inadequate models for finding order, much as Ecclesiastes tracks inadequate models for resolving meaninglessness. In contrast to these human attempts to find order, Genesis then offers the covenant as the means to establish order.

This understanding forms a strong link between Genesis 1–11 and Genesis 12–50 in that humanity’s inadequate attempts serve as prelude to the only successful path: a relationship with God through a covenant not based on mutual need, one that eventually reestablishes the presence of God (in the tabernacle and the temple), God’s means of bringing order through his people.

If there is an offense in Genesis 11, it is found in the selfish motivations of the people thinking that they could profit and build a reputation by pampering God. But perhaps even more important is the idea that, once again, peoples’ attempts to produce order for themselves by their own efforts and for their own benefit are doomed to fail. God offers the only path to order, and it is through proper relationship with him. He is the source and center of order. So it has always been, and so shall it always be.

In light of this exegesis of the biblical text and understanding of its ancient Near Eastern context, how should we think about the Tower of Babel account? How can our understanding ripple through our lives as followers of Jesus?

God’s plans and purposes have always been to be in relationship with and to dwell among the people he created.

Certainly this passage provokes us to realize that, as often as our approach to God reeks of transactionalism, such thinking deserves no quarter in our understanding of our relationship with him. Potential gain in this life or the next should never be the prime motivator of our faith—God is worthy, and that alone should suffice for us to be committed to him in every aspect of life. I am daily challenged by the reality that God does not need my gifts, my attention, my prayers, my worship, or my companionship. I am in his debt, not he in mine.

Further, we should acknowledge that as much as civilization and culture can be instruments of order, they can also be disruptive. We cannot rely on them to bring ultimate order to our lives or our world. We find rest (order) by taking on the yoke of Christ, not by having all of our insecurities and trials resolved to our satisfaction.

This passage—and all of Genesis—also reminds us that God has planned from the beginning to be with us. We need to have an “Immanuel theology”—“God with us” reflects his desire and our privilege. Immanuel is not just a Christmas story. God’s plans and purposes have always been to be in relationship with and to dwell among the people he created. This was initiated in the Garden of Eden and reflected in the purpose of the temple. It exploded into a new reality in the Incarnation and reached unimagined heights at Pentecost, when Babel was reversed and people spread throughout the world, not in the aftermath of a failed project but with the presence of God within them.

We long for the culmination of these plans and purposes in the new creation: “Look! God’s dwelling place is now among the people, and he will dwell with them. They will be his people, and God himself will be with them and be their God” (Rev. 21:3).

The Tower of Babel account plays its role in Genesis to help us understand what it means to be a follower of God—to be one who has chosen to be a participant in God’s plans and purposes. It is no surprise that this is what Jesus asked of his followers: to give up their own desires and pathways to follow him. His name is to be hallowed, not our own; his will be done, not our own; his kingdom come, not our own.

I am personally challenged to be a true follower of Jesus by adopting these perspectives about the nature of my faith and the reason for my commitment to Christ. The Bible story that fascinated me as a young boy continues to speak to me many decades later, though I understand its message in very different terms. I am personally challenged by it to live as a true follower of Jesus by daily reminding myself that my faith is not about me—it is about the God I seek to serve.

John Walton is professor of Old Testament at Wheaton College and the author of numerous books, including Ancient Near Eastern Thought and the Old Testament and, forthcoming, Wisdom for Faithful Reading: Principles and Practices for Old Testament Interpretation.