Christian History began ten years ago in the mind of Dr. A. Kenneth Curtis. Ken is president of Gateway Films, a Christian film company he founded more than twenty years ago, and chairman of its companion, Vision Video, Inc. His films have garnered more than 30 awards, including an international Emmy.

Ken earned his Ph.D. in communications from Walden University, Minneapolis, Minnesota, and has received an honorary doctorate from another alma mater, Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary in South Hamilton, Massachusetts. Ken continues as senior editor for Christian History and serves on the board of Christianity Today, Inc. He also publishes Glimpses, a lively church-bulletin insert about church history. He recently became a grandfather.

Editors Kevin Miller and Mark Galli joined Ken in his office—a converted barn in the gently rolling hills of eastern Pennsylvania—to get the story on Christian History’s early days.

Christian History: Where did you get the idea to start this magazine?

Ken Curtis: Our fledging film company had just put out a film on John Hus, the Bohemian reformer. I had an opportunity to show it at a Christian Film Distributors Association meeting. As I was introducing the film, I asked, “How many of you know who John Hus was?” Out of several hundred people, about three hands went up.

I was surprised, but not nearly as much as later, when I was about to show the film to a group of pastors. Again I asked, “How many of you know who John Hus was?” Only half the group had even heard of him.

I realized that we contemporary Christians have little idea where we came from. Lay people are nearly totally unaware of our past, and ministers receive only a semester or two of church history—hardly enough to get a good grasp of the past.

So we prepared a 16-page guide to accompany the film, to give people more background. For our next film, First Fruits, the story of Count Zinzendorf and the first Moravian missionaries, we upgraded the pamphlet to a magazine format. The response was heartening, so we continued by publishing issues for our films on John Wesley and John Wycliffe.

When did it become a regular magazine?

Starting with the first issue, people were saying, “How can I sign up for this?” It soon became apparent the magazine deserved a life of its own. Our issue on Ulrich Zwingli, our fourth, was the first that didn’t accompany a film. At that point, we announced we would try to publish the magazine quarterly.

We wanted the magazine to introduce lay people to church history, perhaps to become a resource for adult-education classes. Mostly, we wanted to create an appetite, a hunger for knowing the history of the church.

What was the response?

It was two-sided.

On the one hand, people were discovering and loving the magazine. A man from Switzerland told me how much his seminary there appreciated the issue on Zwingli—extra copies were placed in the men’s room for reading there!

On the other hand, experts in Christian publishing were telling me, “starting a magazine is more complicated than you realize. With no capital and no proven constituency, you’re not going to make it.”

In one sense, they were right. I had no idea how to build circulation or to find capital to roll out a direct-mail effort. Fortunately, through word of mouth and inserts in our film shipments, the magazine grew pretty quickly on its own to 10,000 subscribers.

What obstacles did you face at the beginning?

Learning how to put together a magazine was a challenge in itself—especially since I had no editorial training. I had to learn how to coordinate a hodgepodge of articles and images into a pleasing and logical flow. I had to learn proofreading and printer’s jargon. I still can’t remember if a comma goes inside or outside punctuation marks—it’s ridiculous how many times I had to look up that kind of stuff.

So we struggled simply to get each issue organized and published on time. Sometimes that required desperate measures. We got behind on the Zwingli issue, for example, and I felt I needed a professional journalist to help us out. So I called Mark Fackler, who teaches communications at Wheaton Graduate School, and said, “Hey, Mark, I’ve got a couple of free tickets to the Phillies game on Thursday night. Why don’t you come in Wednesday through Friday?” We worked around the clock, except for the excursion to the ballgame, and managed to meet the deadline.

Furthermore, my history background was limited, so I felt inadequate to oversee the magazine—though I felt my non-professional status would keep me in touch with the reader.

You make yourself sound like the least likely person to ever start a church-history magazine.

We certainly had to depend on on-the-job training. Sometimes we did find ourselves in predicaments. As we were finishing the issue on the Anabaptists, I had to take a film trip to Europe, so I left the last stages of the issue in the hands of others. When I returned, they handed me a proof of the cover. The only English words on the entire cover were Christian History. Fortunately, at the last minute we were able to insert a small line at the top—The Radical Reformation: The Anabaptists to give readers some clue as to what the issue was about.

Sometimes our editorial challenges were solved serendipitously. We needed a color image of Wycliffe for the cover, but we couldn’t find the original painting—no English museum or university knew where it was. As the deadline loomed, we phoned another English art museum we’d heard about, but we misdialed and ended up reaching an English pub.

We explained what we wanted, not realizing the mix-up, and the bartender said, “I know where that picture is.” It was in his town, in the Great Hall of the Manchester Town Hall.

Christian History’s original elements—themes, many visuals, columns like “Did You Know”—are still proving to be the best way to organize the magazine. How did you determine the original format?

Actually, it came together within half an hour, although the ideas had been percolating for some time. By the time we sat down to construct a magazine, it fell into place: themes would help us explore issues at some depth; visuals would make history real; a bibliography would help people explore further; interesting facts at the beginning would draw people in; original writings would help people feel the era, and so on.

You keep using; the word we. Who is we?

Christian History was always a team effort. Our film staff (about five people) put in extra time. In particular, Mark Tuttle did a lot of the picture research, and Robin Heller helped solve design problems. But we didn’t have a full-time person helping with the magazine until Issue 16, so various resource people pitched in, mostly on evenings and Saturdays.

Four years ago, your Christian History Institute decided to transfer the magazine to Christianity Today. Why?

It became more than we could handle. It began taking us away from our film work, and we felt we had something unique to contribute there.

We also realized the magazine had more potential than we could help it realize. We had the magazine well established, but it would take someone with more expertise to raise it to new heights.

So for some time I had prayed and kept my eyes open for possible publishers. Then at the end of an Evangelical Press Association meeting in Indianapolis, as I was leaving, I saw Harold Myra, president of Christianity Today, Inc., standing nearby.

Although I’d never met him, I knew who he was, so I walked up to him and said, “Excuse me. I’ve got to run to the airport in ten minutes, but would you have a couple minutes to talk?” I showed him the magazine, which he had already seen, and said, “I’d really like to find a home that would appreciate it for what it is and bring it to its potential.” We took it from there, and now we’re able to reach four or five times as many readers.

There was a sense of divine leading in the creation of this magazine. We needed, sought, and recognized the grace of God for each issue we published. I think it was just as much the leading and grace of God to help us realize we had done what we had been called to do, and it was time to let go and have others carry it forward.

What hopes do you have for Christian History?

I’d like it to become a flagship for a number of church-history projects. For instance, it would be great to have a church-history magazine or books aimed at children. Too many Christian young people grow up ignorant about their heritage. Then they go to a secular college and hear how the church has caused great harm in Western society. That’s hardly the whole story, but when they hear that half-truth, Christian young people often go astray.

Why should people care about church history?

First, it’s just plain interesting. As we were preparing the first issue, I told one of our staff, “You know, I think this may have to be an ongoing magazine—maybe a quarterly.”

She responded, “But is there enough material to keep it going?” Well, there have been thirty-some issues, and we’re just scratching the surface. We’ve had only a taste.

Second, a knowledge of history is vital for the church’s life. As I said in my first editorial [in Issue 2]: “Our conviction is that the Lord of history will continue to direct and lead his people to new levels of understanding and obedience in the future as he has in the past. We believe that we are better prepared to discern his leading as we are grounded in our heritage.”

I recently received a fund-raising letter from a Christian university. It implied strongly that this particular college is “the faithful strand of God’s elect.”

But history shows that we each are just part of a larger tapestry of God’s handiwork. You study the Waldensians, and you realize the roots of the Reformation began way before 1517. You study Medieval monasticism, and you see a deep respect for the authority of the Bible long before Luther. You look at Francis of Assisi and see that concern for nature and the simple life were Christian ideas long ago.

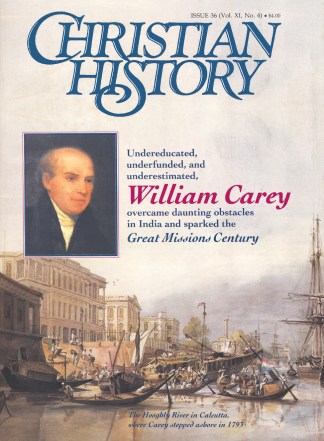

History also shows us that some apparent failures can become great instruments of God—William Carey, for example. And some supposed successes petered out as time went on—take the early dominance of Arianism, for example.

History gives us hope that one person can make a difference. But it also gives us a humility that recognizes others have come before us to prepare the way and others will follow to further our work.

Copyright © 1992 by the author or Christianity Today/Christian History magazine. Click here for reprint information on Christian History.