In this series

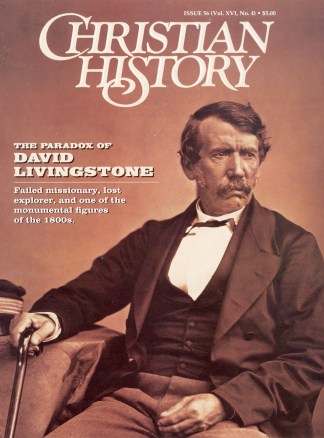

If David Livingstone hadn’t become an explorer, he could easily have made a good living at writing. His descriptions of Africa are some of the best English prose. The following are but brief, condensed excerpts of the 1858 Harper & Brothers edition (732 pages) of Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa.

Faces in the barks of trees

In the deep, dark forests near each village, you see idols intended to represent the human head or a lion, or a crooked stick smeared with medicine, or simply a small pot of medicine in a little shed, or miniature huts with little mounds of earth in them. But in the darker recesses we meet with human faces cut in the bark of trees, the outlines of which, with the beards, closely resemble those seen on Egyptian monuments. Frequent cuts are made on the trees along all the paths, and offerings of small pieces of manioc roots or ears of maize are placed on branches.

There are also to be seen every few miles heaps of sticks, which are treated in cairn fashion, by every one throwing a small branch to the heap in passing; or a few sticks are placed on the path, and each passer-by turns from his course and forms a sudden bend in the road to one side.

It seems as if their minds were ever in doubt and dread in these gloomy recesses of the forest, and that they were striving to propitiate, by their offerings, some superior beings residing there.

Oozing poison

Feeling something running across my forehead as I was falling asleep, I put up the hand to wipe it off and was sharply stung both on the hand and head; the pain was very acute. On obtaining a light, we found that it had been inflicted by a light-colored spider, about half an inch in length, and one of the men having crushed it with his fingers, I had no opportunity of examining whether the pain had been produced by poison from a sting or from its mandibles. No remedy was applied, and the pain ceased in about two hours.

Extortion

While at the ford of the Dasai, we were subjected to a trick, of which we had been forewarned by the people of Shinte. A knife had been dropped by one of Kangenke’s people in order to entrap my men; it was put down near our encampment, as if lost, the owner in the meantime watching till one of my men picked it up.

Nothing was said until our party was divided, one half on this, and the other on that bank of the river. Then the charge was made to me that one of my men had stolen a knife. Certain of my people’s honesty, I desired the man, who was making a great noise, to search the luggage for it; the unlucky lad who had taken the bait then came forward and confessed that he had the knife in a basket, which was already taken over the river.

When it was returned, the owner would not receive it back unless accompanied with a fine. The lad offered beads, but these were refused with scorn. A shell hanging round his neck, similar to that which Shinte had given me, was the object demanded, and the victim of the trick, as we all knew it to be, was obliged to part with his costly ornament. I could not save him from the loss.

I felt annoyed at the imposition, but the order we invariably followed in crossing a river forced me to submit. The head of the party remained to be ferried over last; so, if I had not come to terms, I would have been (as I always was in crossing rivers which we could not swim) completely in the power of the enemy.

Charming the demons

There was a procession and service of the mass in the cathedral [in Loanda]; and, wishing to show my [African] men a place of worship, I took them to the church, which now serves as the chief one of the [Roman Catholic] see of Angola and Congo.

There is an impression on some minds that a gorgeous ritual is better calculated to inspire devotional feelings than the simple forms of the Protestant worship. But here the frequent genuflexions, changing of positions, burning of incense, with the priests’ back turned to the people, the laughing, talking, and manifest irreverence of the singers, with firing of guns, etc., did not convey to the minds of my men the idea of adoration. I overheard them, in talking to each other, remark that “they had seen the white men charming their demons,” a phrase identical with one they had used when seeing the Balonda beating drums before their idols.

Dancing and mourning

The chief recreations of the natives of Angola are marriages and funerals. When a young woman is about to be married, she is placed in a hut alone and anointed with various unguents, and many incantations are employed in order to secure good fortune and fruitfulness.

Here, as almost everywhere in the south, the height of good fortune is to bear sons. They often leave a husband altogether if they have daughters only. In their dances, when anyone may wish to deride another, in the accompanying song a line is introduced, “So-and-so has no children and never will get any.” She feels the insult so keenly that it is not uncommon for her to rush away and commit suicide.

After some days, the bride elect is taken to another hut, and adorned with all the richest clothing and ornaments that the relatives can either lend or borrow. She is then placed in a public situation, saluted as a lady, and presents made by all her acquaintances are placed around her. After this she is taken to the residence of her husband, where she has a hut for herself, and becomes one of several wives, for polygamy is general. Dancing, feasting, and drinking on such occasions are prolonged for several days.

In cases of death the body is kept several days, and there is a grand concourse of both sexes, with beating of drums, dances, and debauchery, kept up with feasting, etc., according to the means of the relatives. The great ambition of many of the blacks of Angola is to give their friends an expensive funeral. Often, when one is asked to sell a pig, he replies, “I am keeping it in case of the death of any of my friends.” A pig is usually slaughtered and eaten on the last day of the ceremonies, and its head thrown into the nearest stream or river.

A native will sometimes appear intoxicated on these occasions, and, if blamed for his intemperance, will reply, “Why! my mother is dead!” as if he thought it a sufficient justification. The expense of funerals is so heavy that often years elapse before they can defray them.

Bites like sparks of fire

During our stay at Tala Mungongo, our attention was attracted to a species of red ant which infests different parts of this country. It is remarkably fond of animal food. The commandant of the village having slaughtered a cow, slaves were obliged to sit up the whole night, burning fires of straw around the meat, to prevent them from devouring most of it.

These ants are frequently met with in numbers like a small army. At a little distance, they appear as a brownish-red band, two or three inches wide, stretched across the path, all eagerly pressing on in one direction. If a person happens to tread upon them, they rush up his legs and bite with surprising vigor.

The first time I encountered this by no means contemptible enemy was near Cassange. My attention being taken up in viewing the distant landscape, I accidentally stepped upon one of their nests. Not an instant seemed to elapse before a simultaneous attack was made on various unprotected parts, up the trousers from below, and on my neck and breast above. The bites of these furies were like sparks of fire, and there was no retreat. I jumped about for a second or two, then in desperation tore off all my clothing, and rubbed and picked them off seriatim as quickly as possible.

Ugh! they would make the most lethargic mortal look alive. Fortunately, no one observed this encounter, or word might have been taken back to the village that I had become mad.

Headhunters

The father of Moyara was a powerful chief, but the son now sits among the ruins of the town, with four or five wives and very few people. At his hamlet, a number of stakes are planted in the ground, and I counted 54 human skulls hung on their points. These were Matebele, who, unable to approach Sebituane on the island of Loyéla, had returned sick and famishing. Moyara’s father took advantage of their reduced condition, and after putting them to death, mounted their heads in the Batoka fashion. The old man who perpetrated this deed now lies in the middle of his son’s huts, with a lot of rotten ivory over his grave.

When looking at these skulls, I remarked to Moyara that many of them were those of mere boys. He assented readily, and pointed them out as such. I asked why his father had killed boys.

“To show his fierceness,” was the answer.

“Is it fierceness to kill boys?”

“Yes; they had no business here.”

When I told him that this probably would insure his own death if the Matebele came again, he replied, “When I hear of their coming, I shall hide the bones.”

He was evidently proud of these trophies of his father’s ferocity, and I was assured by other Batoka that few strangers ever returned from a visit to this quarter. If a man wished to curry favor with a Batoka chief, he ascertained when a stranger was about to leave, and waylaid him at a distance from the town, and when he brought his head back to the chief, it was mounted as a trophy, the different chiefs vying with each other as to which should mount the greatest number of skulls in his village.

Unholy rollers

The chief of Monze came to us on Sunday morning, wrapped in a large cloth and rolled himself about in the dust, screaming, “Kina bomba,” as they all do. The sight of great naked men wallowing on the ground, though intended to do me honor, was always very painful; it made me feel thankful that my lot had been cast in such different circumstances.

One of his wives accompanied him; she would have been comely if her teeth had been spared; she had a little battle-axe in her hand, and helped her husband to scream. She was much excited, for she had never seen a white man before.

Gospel tears

There [in Kuruman] a man scorned to shed a tear. It would have been tlolo, or “transgression.” Weeping, such as Dr. Kane describes among the Esquimaux, is therefore quite unknown in that country.

But I have witnessed instances like this: Baba, a mighty hunter—the interpreter who accompanied Captain Harris, and who was ultimately killed by a rhinoceros—sat listening to the gospel in the church at Kuruman, and the gracious words of Christ, made to touch his heart, evidently by the Holy Spirit, melted him into tears; I have seen him and others sink down to the ground weeping.

When Baba was lying mangled by the furious beast which tore him off his horse, he shed no tear but quietly prayed as long as he was conscious. If these Batoka ever become like him, and they may, the influence that effects it must be divine.

Lie-detectors

As we came away from Monina’s village, a witch doctor, who had been sent for, arrived, and all Monina’s wives went forth into the fields that morning fasting. There they would be compelled to drink an infusion of a plant named goho, [which] is performed in this way.

When a man suspects that any of his wives has bewitched him, he sends for the witch doctor, and all the wives go forth into the field and remain fasting till that person has made an infusion of the plant. They all drink it, each one holding up her hand to heaven in attestation of her innocence. Those who vomit it are considered innocent, while those whom it purges are pronounced guilty and put to death by burning. The innocent return to their homes and slaughter a cock as a thank offering to their guardian spirits.

The practice of ordeal is common among all the Negro nations north of the Zambezi. The slightest imputation makes them eagerly desire the test; they are conscious of being innocent, and have the fullest faith in the muavi detecting the guilty alone; hence they go willingly, and even eagerly, to drink it. The Barotse, for instance, pour the medicine down the throat of a cock or of a dog, and judge of the innocence or guilt of the person accused according to the vomiting or purging of the animal.

I happened to mention to my own men the water-test for witches formerly in use in Scotland: the supposed witch, being bound hand and foot, was thrown into a pool; if she floated, she was considered guilty, taken out, and burned. But if she sank and was drowned, she was pronounced innocent. The wisdom of my ancestors excited as much wonder in their minds as their custom did in mine.

Copyright © 1997 by the author or Christianity Today/Christian History magazine. Click here for reprint information on Christian History.