In this series

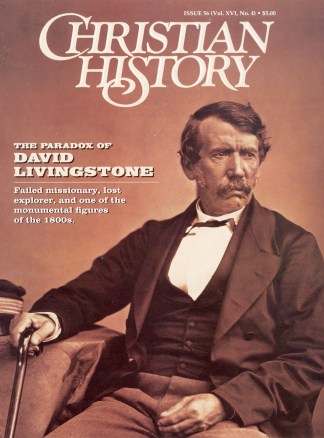

By 1858 seven years had passed since Livingstone first saw the great Zambezi River, and for seven years, Livingstone had eagerly anticipated a second exploration of its vast waters. As in all his travels, his immediate goal was to open a route to Africa’s interior.

“If Christian missionaries and Christian merchants can remain throughout the year in the interior of the continent,” he wrote, “the slave trader will be driven out of the market.”

This was the legacy Livingstone craved, and this river—500 yards wide, 1,000 miles from the sea—would be the greatest tool imaginable.

Instead the expedition turned into his greatest disaster. Livingstone was considered a national hero when he left on his Zambezi Expedition; when he returned, he was thought a madman and a failure. “We were promised cotton, sugar, and indigo, and of course we get none,” lamented the Times. “We were promised converts to the gospel, and not a one has been made.”

What happened on this infamous expedition reveals a recurring irony in the study of great people. In this case, the qualities in Livingstone that brought him success—his singlemindedness, his courage, his stubborn perseverence—also led him into his biggest failure.

Wrong river

The two-year expedition was funded by the British government. Accompanying Livingstone were naval officer Norman Bedingfield, a zealous abolitionist; young geologist Richard Thornton; John Kirk, medical officer; Thomas Baines, storekeeper; George Rae, the Scottish engineer of the ship; and Charles Livingstone, David’s brother, who, as a clergyman, was to be the expedition’s “moral agent.”

The expedition’s troubles began almost immediately. When the party arrived at what appeared to be the mouth of the Zambezi (a river Livingstone called “God’s Highway”), Livingstone was too sick, tired, and drugged to enjoy the moment. Two weeks would pass before a passing trader informed the expedition they were not on the Zambezi but a small river just south of their goal.

The party made its way to the Zambezi and started up the river on the HMS Pearl. Immediately the ship became stuck, and Bedingfield, a senior officer in the Royal Navy, began arguing procedure with the Pearl’s captain. When Livingstone arbitrarily sided against his second-in-command, Bedingfield offered his first letter of resignation.

With the river falling 10 inches a day, the Pearl ran aground again and again. So on an island a mere 50 miles from the ocean, the party unloaded their goods and their “portable” steam ship, dubbed the Ma Robert (to pass difficult stretches of the river, it had been designed to be taken apart and reassembled). That’s when another argument between the captain and Bedingfield broke out.

Livingstone blamed the row on bowel trouble (an ailment he faulted for many problems) and suggested Bedingfield try a laxative. Bedingfield said the advice “had been better addressed to a child” and tendered his resignation—this time for good. (The squabble was followed by a flurry of letters from Livingstone to England, absolving himself of any blame and accusing Bedingfield of, among other misdeeds, insubordination, cowardice, and refusing to work on Sundays.)

In the meantime, Livingstone, knowing every moment spent in the Zambezi’s delta was an open invitation to malaria, headed for Tete, the village he visited in 1856, to set up a base. With his glut of supplies, however, that required several trips up and down a difficult 250-mile stretch.

Just getting to what was supposed to be the starting point of the expedition, then, took four months. And the expedition had already lost one member.

Between a rapid and a cataract

Livingstone’s next step was to explore the Kebrabasa Rapids (now Cabora Bassa). Leaving his brother in charge at Tete, Livingstone, Kirk, and Rae set out for the gorge. At the second rapid, however, their launch was swung around and hit a rock, gashing a hole into the port bow.

Shaken, the men opted to survey the rapids by land. But with each rapid more dangerous than the last, “God’s Highway” had reached a dead end.

Livingstone returned to Tete and wrote, “Things look dark for our enterprise. This Kebrabasa is what I never expected. No hint of its nature ever reached my ears.”

Though more ground reconnaissance only confirmed these fears, Livingstone remained hopeful: perhaps, with a different water craft, at flood stage, when most waterfalls would be completely submerged, he could surmount the gorge. But even he recognized this would be risky.

The impatient Livingstone, however, refused to wait for the Zambezi to rise. Instead he decided to explore the Shire River, which joined the Zambezi 100 miles from the sea.

Livingstone quickly began to believe the Shire offered even better access to Africa’s interior. The Shire began 80 yards wide and only broadened upstream. And the natives, though suspicious of his expedition, were not hostile. The Maganja, who had a reputation as belligerent and dangerous, were even willing to trade.

Again geography put a halt to his plans. The party reached a series of cataracts (which Livingstone named Murchison Falls) that could not be passed. So it was back to the Zambezi to see once more if the Kebrabasa Rapids were passable yet. They weren’t.

Then it was back to the Shire. Then back to Tete and to more personnel problems.

His brother Charles had accused Thornton of being lazy, and Baines, of stealing. Livingstone naturally believed his brother, but it is now clear that Charles (like his brother) was prone to making false reports about those with whom he disagreed. Livingstone ended up dismissing two of his best men on what turned out to be false charges.

With his ever-shrinking crew, Livingstone returned to the Shire again, this time to find its source—the immense Lake Nyasa (now Lake Malawi). If a steamer could be taken apart, put back together just upstream from the cataracts, and placed on Lake Nyasa, Livingstone could create his dream: an English colony in the center of Africa that would stanch the slave trade.

Yet now it was not geography, personnel problems, nor poor management but the Portuguese who stood in the way: following in Livingstone’s tracks, they had laid claim to key sections of the Shire. Livingstone was forced to look for another way to the great lake.

He put his hopes now in a third river, the Rovuma, which lay 1,000 miles north of the Zambezi’s mouth.

Tossed like twigs

The Rovuma, however, would have to wait, for Livingstone had a promise to keep. On his previous expedition, he had brought the Makololo tribe to Tete from their homeland, rescuing them from slavers. At the time, he promised them that upon his return to Africa, he would lead them back to their home. It was this promise, in fact, that had pushed him to return to Africa so quickly. So back to the Zambezi he went.

Escorting the Makololo was a long, relatively uneventful journey. On the way, however, Livingstone found that slave traders routinely claimed to be his children to gain favor and cheap slaves. Livingstone was horrified, not only at the suggestion of illicit behavior but more importantly this: the country he had opened in order to stop the slave trade had become a highway for it: “We were made the unwilling instruments of extending the slave trade. … Had we not been under obligations to return with the Makololo to their own country, we should have left the Zambezi.”

When he arrived at Sesheke, Livingstone was more desperate than ever to prove the Zambezi navigable. He obtained canoes, and he navigated from Victoria Falls to the Kebrabasa Rapids without incident. But Livingstone wanted to show he could descend the gorge, too. When he tried, the canoes were tossed like twigs in the whitewater. His men were somehow able to swim to shore safely and recover the canoes.

“We now left the river and proceeded on foot,” Livingstone later recounted, “sorry we had not done so the day before.”

Personnel issues surfaced again, this time with his brother, Charles. “He seems to let out in a moment of irritation a long pent-up feeling,” he wrote. “In going up with us now he is useless. … He often expected me to be his assistant instead of him acting as mine.”

In fact, Charles almost got himself killed after he kicked a Makololo chief while arguing with his brother. The chief, inches from plunging a spear into the minister’s chest, only stopped at David’s request.

Still seething from the slave traders’ exploitation of his travels and discouraged by his experience at the Kebrabasa Gorge (amazingly, he still maintained it would be navigable with a powerful steamer), Livingstone returned to Tete ready to write off the Zambezi altogether, concentrating his efforts on Lake Nyasa.

“We have kept the faith with the Makololo,” he said, and then admitted in disappointment, “though we have done little else.”

Missionary mess

Livingstone naturally did not share his pessimism with the English government. Instead he encouraged his country to lay claim to the Nyasa area, portraying the valley as an Eden awaiting residents.

At the time, the government had no interest in creating and maintaining a colony in central Africa, but it supported Livingstone’s plans to explore Nyasa and his desire to establish a mission near the lake. So it sent a new boat to replace the Ma Robert along with a staff for the mission.

The staff that arrived included five Africans picked up from the Cape of Good Hope, a bishop, three clergymen, and two laborers. Each of the Europeans had been inspired by Livingstone’s famous Cambridge address, which pleaded for more missionaries to Africa. But Livingstone commented, “It was a puzzle to know what to do with so many men.” For Livingstone, a natural loner, this crowd was too much.

On the other hand, the missionaries’ awe for Livingstone was quickly diminished when they discovered he had greatly exaggerated the livability of the Shire valley.

And when the missionaries became enmeshed in inter-tribal warfare (in an attempt to free slaves), Livingstone’s work of building relationships with tribes was undone. To every tribe of the area, it would appear the group had taken sides.

Death toll

This news was compounded by word that more people were coming to the mission at Magomero, including Livingstone’s wife, Mary, and two other women. The land was far too harsh for the English women, but Livingstone had written so kindly of the Shire valley that they thought it safe to come. Now Livingstone’s troubles multiplied.

Livingstone took a handful of men to meet the women’s ship, but the canoe carrying the bishop and another missionary capsized, soaking the men. Weak and ill, with no medicine or change of clothing, both men died.

Meanwhile the missionaries who remained in Magomero were struck by famine and disease.

Livingstone, upon greeting his wife, was met with rumors of a tryst between her and another arriving missionary. The rumors were untrue, and Livingstone never really believed them. (The idea of a handsome, 30-year-old missionary pursuing a married woman known for being “coarse, vulgar” and obese, is highly unlikely. The missionary had only sought to calm Mary down during her drunken bouts of hysteria.) But the stories weakened Mary Livingstone’s spirit while the jungle weakened her body. Three months later, she was dead.

Mary’s death was immediately followed by word that the missionaries had fled Magomero upon word that tribal warfare was on the rise.

Then the waters of the Shire receded so much, it would be impossible to ascend them for another six months.

Desperate to get away from the situation, Livingstone left to explore the Rovuma River but found the river far too shallow to navigate.

When he returned to the Shire, Livingstone discovered that a steady drought meant not only famine but also too little water to head upstream. Furthermore, two more members of the mission had died, and the others were almost out of food. Kirk and Charles Livingstone asked to be released. Now only six whites remained.

The singleminded Livingstone still believed all could be saved if he could just get a steamer on Lake Nyasa. He never got the chance. Just before leaving for the lake to get provisions for the group, the mission’s new bishop arrived carrying a letter from the British government.

The letter said the expedition was being recalled.

For better or worse?

In one respect, the news came as a relief. By being recalled, Livingstone did not need to concede defeat—though it is unlikely he would have done so.

As he packed his supplies, he was told the new bishop was pulling the mission off the mainland. Livingstone knew immediately that natives would now be much worse off because the Portuguese would simply exploit for the slave trade areas Livingstone had opened.

In the long run, Livingstone’s legacy helped prompt the British government to step in and put a stop to the African slave trade. But in the meantime, Livingstone was left to roll over in his mind a statement he had made some 13 years earlier: “The natives always become much worse somehow after contact with the Europeans.”

Ted Olsen is assistant editor of Christian History.

Copyright © 1997 by the author or Christianity Today/Christian History magazine. Click here for reprint information on Christian History.