The first attempt to replicate the United States’s diplomatic advocacy for beleaguered believers worldwide has come to an end.

Five years ago, Canada’s Conservative party campaigned for a new office to champion the cause of international religious freedom (IRF). The office opened in 2013, looking to complement the strengths of the US State Department’s IRF office that it was modeled after.

But six months after the Conservatives lost national elections to the Liberal party, the four-person, $5 million Office of Religious Freedom (ORF) has been shut down.

“Our government shares the same conviction as the previous government, but it assesses the consequences of its chosen method of promoting this conviction differently,” said foreign affairs minister Stéphane Dion during a speech, according to The Globe and Mail. “I am referring to freedom of religion or belief, which we will defend tooth and nail, but not through the office that the Harper government specifically set up for this purpose.”

Members of prime minister Justin Trudeau’s new government are opting instead to fold religious rights into a broader human rights office.

“We believe that human rights are better defended when they are considered, universal, indivisible, interdependent and interrelated, as set out in the Vienna Declaration,” said Dion during the speech. He foreshadowed the decision in a January speech, noting, “How can you enjoy freedom of religion if you don’t have freedom of conscience? Freedom of speech? Freedom of mobility?”

The chairman of the ORF’s religious advisors doubts this explanation. “If the ORF is not being closed because it is not working, it is likely being closed because the government does not place a priority on the work itself,” wrote Raymond J. De Souza for the National Post. “That reading is rendered more plausible given that the foreign affairs department (now called Global Affairs) undertook no consultations with the ORF’s advisory committee…. If there was a commitment to religious freedom, but through a different means, such consultation would have been an obvious starting point.”

The Economist speculates that Liberals object more to the Conservative party that founded the ORF than the office itself.

Former prime minister Stephen Harper first suggested its creation following the assassination of Pakistani politician Shahbaz Bhatti, an outspoken proponent for his country’s minorities.

“We’re deeply disappointed,” Bruce Clemenger, president of the Evangelical Fellowship of Canada, told CT. “The office had became a go-to place for us to raise concerns about religious freedom to the government, and it established a level of expertise within the Canadian government.”

An Ottawa academic and Ukrainian Catholic, Andrew Bennett, was nominated as the office’s first and only ambassador in 2013. Bennett left his position in March to join the Christian think tank Cardus and lead its new interfaith initiative, Faith in Canada 150.

The need for the office has been contested since it opened in 2013. Some worried it would be prone to favor Christianity, since the majority of consultants in an early closed-door meeting were Christians. Critics also suggested that it was a “misguided attempt to inject religion into foreign policy, and some have expressed concern that it would be biased toward the persecution of Christians,” Religion News Service reported in 2013.

But the office’s closure was protested by a variety of faith groups, including representatives from the Jewish, Sikh, and Muslim communities, who called its work valuable. “While these projects do not always make headlines, we believe they laudably reflect a practical and effective role Canada can play in mitigating the plight of persecuted religious minorities around the world,” they wrote.

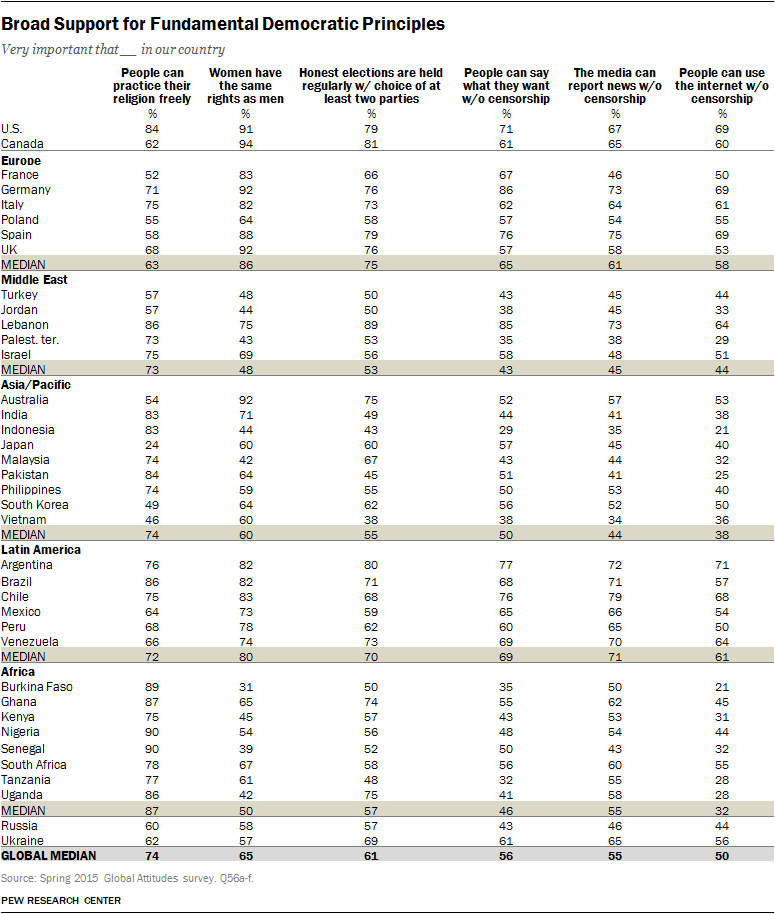

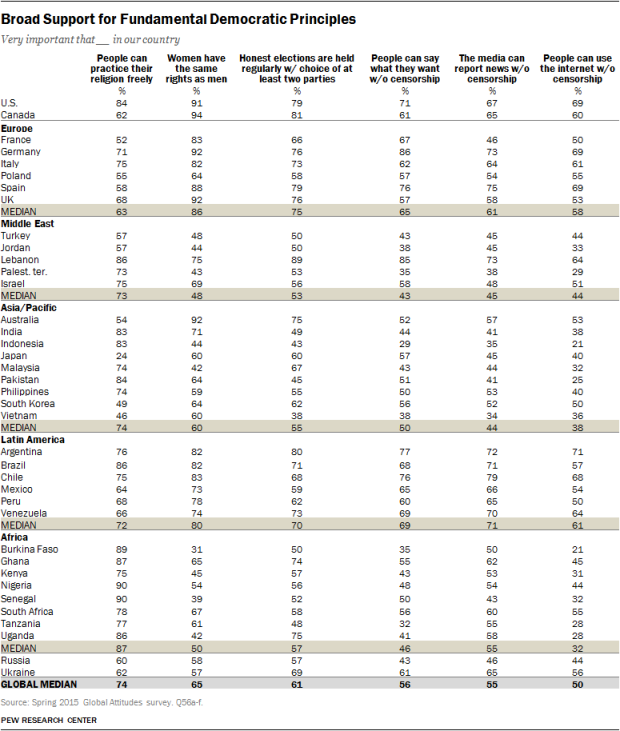

Canadians in general are only moderately enthusiastic about religious freedom: 62 percent said that it was very important that people can practice their religion freely in their country, compared to 84 percent in the United States. Canadians ranked religious freedom below equal rights for women (92%) and two-party, honest elections (81%), according to a Pew Research Center study of 38 countries last year.

Canada’s concern for religious freedom ranked in the bottom third of the countries Pew surveyed. Religion was the most valued democratic principle, Pew found, garnering the support of 74 percent of people globally.

Globally, African countries were most likely to value religious freedom, with 90 percent of Nigerians and Senegalese calling it the most important freedom. (Five of the top seven countries were in sub-Saharan Africa, and the regional median was 87 percent.)

Almost three out of four citizens of Asian countries also valued religious freedom, though the range from the regional median (74%) was larger. The vast majority of Indians and Indonesians (both 83%) highly prioritize religious freedom, while less than half of South Koreans (49%), Vietnamese (46%), and Japanese (24%) said the same.

Brazil had the highest support (86%) for religious freedom out of any Latin American country, followed by Argentina (76%) and Chile (75%). Support was the lowest in Mexico (64%) and Venezuela (66%). The regional median was 72 percent.

Europe had the lowest regional median (63%). Italians (75%) and Germans (71%) were most likely to support religious freedom, while French (52%) and Polish (55%) citizens were least likely.

Support for religious freedom did not strongly correlate with participation in a particular faith, Pew found.

“Freedom of religion is widely embraced around the world, but it is particularly significant to people who place high importance on religion in their lives,” stated Pew. “In 34 nations, those who say religion is very important in their own lives are more likely to believe it is very important to live in a country where people can practice their religion freely.”

CT noted when Bennett was named the religious freedom ambassador (two years late), as well as several cases where Canada's Immigration and Refugee Board denied asylum because applicants demonstrated poor knowledge of Christian doctrine.

[Photo courtesy of ORF – Facebook]