David Fitch is an unusual church planter because he is also a theologian, occupying the Lindner Chair of Evangelical Theology at Northern Seminary. And he is an unusual theologian and professor because he is a church planter, immersed in Life on the Vine, a “missional” church in the northwest suburbs of Chicago. This double life has made his writing, both online at his weblog, Reclaiming the Mission, and in his provocative book The Great Giveaway, must-reading in emerging, evangelical, and mainline settings. One of Fitch’s great gifts is his willingness to challenge his readers’ assumptions, and his own. Here, he turns the tables on our big question for 2008, “Is our gospel too small?”

Can the gospel be too big? For some of us in the missional church movement, this question borders on heresy. We regularly caution that the gospel is not only about what Jesus can do for me. It is primarily about the transformation of our very way of life into God’s mission for the world. We resist any temptation to turn the gospel into anything that might be too “user friendly.” The mission of God (missio Dei), so we proclaim, must be all-encompassing, and we must become participants in it.

Yet for all the good in this approach, there may be another heresy beneath the surface. For in protecting the bigness of the gospel, we risk making the Christian life inaccessible to those outside of it. As a result, amid the current swell of appreciation for missio Dei theology in American churches, and the outcries against a gospel that has become too small, I find myself concerned about the ways we may unintentionally be making the gospel too big.

Theologian Darrell Guder has observed that the church is always in the process of reducing the gospel in order to translate it for a given culture. In translating the gospel, we inevitably emphasize certain aspects of it over others. This unavoidable process only becomes a problem when we become fixated on a particular translation, permanently shrinking the gospel instead of leading people into its fullness. Guder calls this process the “challenge of reductionism,” and calls for the “continual conversion” of the church, in which the church must always re-inhabit each new context with the gospel in a way that is suitable for its particular time and place. Being the gospel in the world, therefore, demands a continual traveling back and forth from the grand scope of all that God is doing in Christ to the simple offer of salvation to the stranger and back again.

Guder is proposing that the church must follow this process to be faithful missionaries of the gospel. But there is a complementary danger of refusing to reduce the gospel out of disdain for a particular culture’s sin. We resist the accommodation of the gospel to a culture that seems to have such evident deficiencies. But in so doing, we refuse to speak a gospel that can be heard by those afflicted by these very cultural ills. We insist, maybe sinfully, on keeping the gospel out of reach.

My wife and I learned this when we moved to the northwest suburbs of Chicago to plant a church. Chicago’s suburbs stretch across hundreds of square miles of highways, tollways, subdivisions, monster malls, gated communities, and corporate offices. Thousands of cars speed along the expressways carrying people to their homes, jobs, and children’s sport programs. The breakneck pace pulsates so heavily that it is difficult for any individual not to be swallowed up. The same forces press upon churches as well, urging them to make the gospel as convenient as possible for people on the move.

As we planted the first seeds of our church in this place, I was repulsed by the expectation to turn the gospel into something that could fit people’s schedules or provide immediate, quick-fix spiritual benefits. But in response to the sins of suburbia, I went to the other extreme. I became phobic about our church becoming a supermarket-like pseudo-community providing spiritual goods and services to all comers. With too much self-assurance, I preached sermons on how the church must define its very existence as the extension of God’s mission in the world. Drawing on the great formulations of missional thinkers Lesslie Newbigin and David Bosch, I proudly taught that the church was an extension of the Trinity, gathering the world unto himself. The mission of God would be our very identity, and its cosmic scope would dwarf the forces that seek to shrink our vital gospel into some banal conformity.

My intentions were good, and Bosch and Newbigin still sound as good as ever. But how does this gospel become comprehensible for those lost in the suburbs? Can this incredible vision of God’s work meet those of us who are poor on time, devoid of deep human connection, and with little energy left after 6 P.M. to tend to the mission of God?

Making Converts in Post-Christendom

In those first few years of ministry at Life on the Vine Christian Community, Jack and Suzanne (not their real names) came to us with divorce papers in hand, asking for help. They knew little of the gospel. They had no time for church. Their art careers were the center of their lives, and they couldn’t imagine it any other way. Nonetheless, Jack managed to hang out with a group of us meeting for confession and prayer every Monday night. One ugly sin after another would come up in Jack’s life (as for us all). Together, we would deal with each sin, working out repentance and the forgiveness of Christ in this man’s life. There were some holy moments. Nonetheless, the sins would persist.

One night, as Jack’s marijuana addiction was being dealt with for what seemed the hundredth time, two men in the group lashed out. They asked Jack if he was serious about Christ. If not, they said, he should excuse himself from the group. Jack soon wandered away.

Some might be quick to say that Jack had flat-out rejected the gospel. I hesitate to make that judgment. From my vantage point, Jack just couldn’t get it. He thought he was doing what he was supposed to do: confess sin, repent, receive forgiveness, and go home and try harder. Yet each time, forgiveness and repentance would become the means to the same old ends. He could not grasp the full implications of how God’s forgiveness through Christ might actually change his living. For all our attempts to paint a big picture of God’s mission for Jack, he could not understand what it meant to reorient his entire life toward God in this way. He could not envision the grander life he had been called into.

For me, Jack illustrated the central problem: The wide-reaching implications of the gospel were inaccessible to someone thoroughly shaped by the structures of contemporary society. Surely we know that only the Holy Spirit could ultimately illumine Jack’s heart. Nonetheless, I questioned whether our community’s life and deep sense of God’s mission had been accessible to Jack. He did not have time to make it to every Sunday gathering. Our initiation process into baptism took six months. This was daunting to even the most committed.

Jack illustrated the potential hole in missional churches like ours. We define the church and its life as God’s mission as we incarnate his purposes for the world. Yet we lack the wherewithal to “bridge” those in need from where they are to the mission of God.

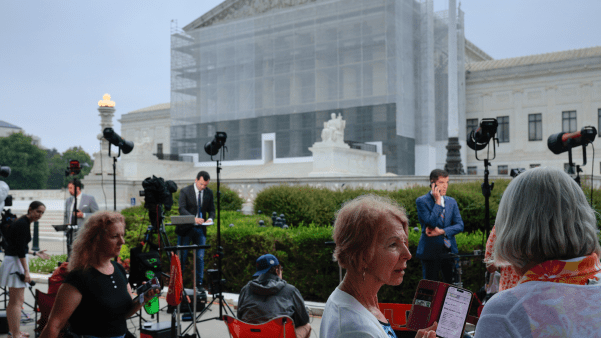

I have often been asked about the number of conversions in missional churches. I hesitate to even answer this question. Part of this is because I believe conversion in missionalsettings takes longer and is often messier. Most missional churches are aimed at so-called “post-Christendom” settings, in which people have no initiation into the Christian faith. Any new convert therefore must first understand the biblical story of God’s mission in and for the world, from Israel all the way to the Second Coming, in order to even know what it might mean to confess that “Jesus is Lord” over his or her life.

This kind of conversion happens over time. It often happens as strangers experience daily life with Christians, learning the story of our lives in Christ. This is why a “tool” for initiating such people into Christ is so important. Someone can “hang” with us for years and not sufficiently enter in unless intentionally guided through a process. For this reason I have suspected that missional churches need a different kind of evangelistic tool that maintains the hugeness of God’s mission, while still inviting people into personal conversion and participation in the work of redemption God is doing.

Becoming Part of the Bridge

This reality hit me hard one night at a pastors’ meeting. As we were discussing our church’s missional efforts, a pastor suggested that while we had successfully preached the life of Christ and his mission, we had in the process made church members timid in the actual task of leading people to Christ. At our church, we have often panned old methods of evangelism that make salvation into a transaction. We wince at any quick prayer that would reduce repentance and faith to a ticket out of hell. We believe this approach has trained people into all the wrong ways of knowing Christ. But on this particular night, we realized our members needed a different kind of evangelistic tool to lead their friends from their former lives into the “new order” of creation.

We have not yet pinpointed what a four spiritual laws diagram or bridge illustration (in which Christ “bridges” the chasm between man and God) might look like for our missional community. Nonetheless, after many conversations, I believe any such tool must accomplish at least two things. First, such an evangelistic tool must lead the new believer in the back-and-forth motion between the bigness of God’s salvation for the world and what he wants to do “for us”: forgive our sins and shape us in the image of his Son. In other words, such a tool should begin with 2 Corinthians 5:19 (“that God was reconciling the world to himself in Christ, not counting men’s sins against them”), move to the personal John 3:16, and go back again. This tool must in effect allow the busy suburban family person to catch a glimpse of the world he or she is not seeing, instead of first appealing to the all-too-familiar “need.” Like a mind-bender movie that helps us see reality in a different way, such a tool would unfold the big picture of God’s “reconciling the world to himself.” This sets the stage that makes possible the words, “whoever believes in him shall not perish but have eternal life.” Such a tool will prepare us to offer a glimpse of a new world order when everything else has become cloudy and dark. It will be composed of stories and pictures, both scriptural and personal.

Second, this evangelistic tool must function from within the context of the community’s life, because it is only here that the words and pictures we share take on flesh and make sense. In post-Christendom settings in which people have no language to comprehend the gospel, an evangelistic tool can make the gospel seem like another lofty idea for achieving a better life. The gospel therefore should not be separated from real lives engaged in living the mission. It is the community that translates the mission of God, through tiny acts of loving one another and the world around us. The community becomes a necessary part of “the bridge.”

At times, we at Life on the Vine have thrown up our hands and said that such community is not possible in suburban life. Yet who is not blessed by a friend who takes the time to offer “a cup of water” in the desert that suburban life can become? These relationships minister the gospel. And out of these relationships, words become explanations of a compelling way of life (1 Pet. 3:15). They make possible that communal moment when we say, “You’ve been hanging around awhile, you know what we’re about; isn’t it time to make a decision to follow Jesus as Lord?” Such a tool should provide the words to make “the invitation to turning” the natural extension of our communal hospitality.

We at Life on the Vine have yet to arrive at this elusive evangelistic tool. We continue to navigate Guder’s “challenge of reductionism” for our context. It is still as busy as ever here, and the gospel should not be minimized to fit the suburbs’ maddening pace. Yet loving our neighbors will mean a constant journey back and forth between big and small: from the bigness of God’s work to translating it for our neighbors to bringing them back into this grand mission all over again. Call it missional commuting: a daily journey between worlds. Fortunately, unlike so many single-driver car trips, it’s a journey our whole church—this unlikely family that’s being grafted into God’s mission—can take together.

Copyright © 2008 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere:

David Fitch will be speaking at the Ancient Evangelical Future conference, October 9-11.

Fitch is founder of a Chicago-area emerging church blog called Up/Rooted.

Previous Christian Vision Project themes were culture in 2006 and mission in 2007. 2008 articles include:

The 30-Day Leviticus Challenge | One church’s experiment in living the most arcane book of the Bible. (July 25, 2008)

From Four Laws to Four Circles | James Choung has found a way to tell the old, old story to a new generation. (June 27, 2008)

When God Disturbs the Peace | Our gospel may be small because we fail to believe that God animates many social movements. (May 30, 2008)

The Poverty of Love | The desert fathers and mothers would know instantly why our gospel is too small. (April 30, 2008)

An Open-Handed Gospel | We have to decide whether we have a stingy or a generous God. (April 3, 2008)

The 8 Marks of a Robust Gospel | Reviving forgotten chapters in the story of redemption. (February 29, 2008)

Singing in the Chains | To be saved means more than we might think. (January 31, 2008)

The Lima Bean Gospel | The Good News is so much bigger than we make it out to be. (January 8, 2008)