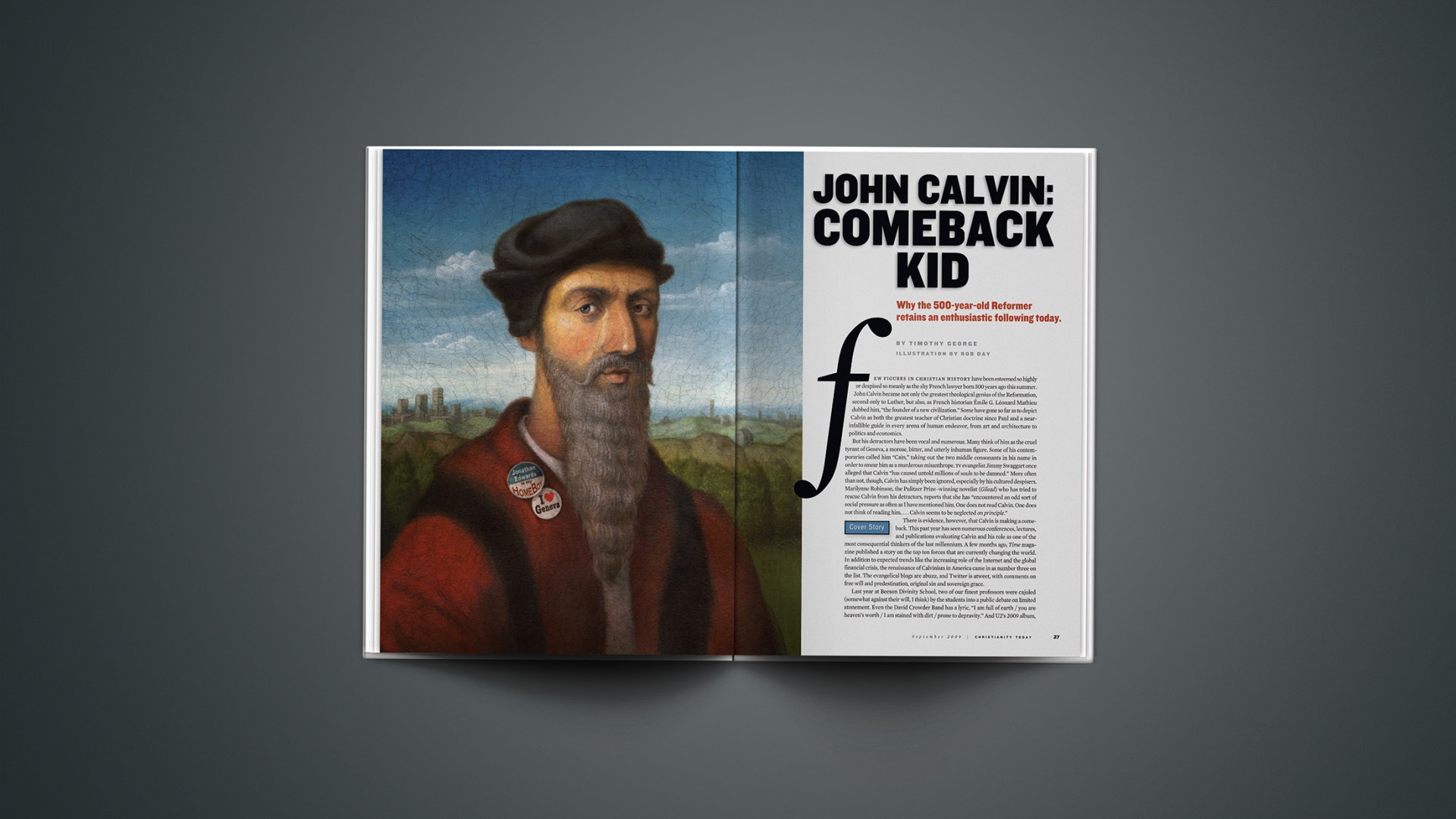

Few figures in Christian history have been esteemed so highly or despised so meanly as the shy French lawyer born 500 years ago this summer. John Calvin became not only the greatest theological genius of the Reformation, second only to Luther, but also, as French historian Émile G. Léonard dubbed him, "the founder of a new civilization." Some have gone so far as to depict Calvin as both the greatest teacher of Christian doctrine since Paul and a near-infallible guide in every arena of human endeavor, from art and architecture to politics and economics.

But his detractors have been vocal and numerous. Many think of him as the cruel tyrant of Geneva, a morose, bitter, and utterly inhuman figure. Some of his contemporaries called him "Cain," taking out the two middle consonants in his name in order to smear him as a murderous misanthrope. TV evangelist Jimmy Swaggart once alleged that Calvin "has caused untold millions of souls to be damned." More often than not, though, Calvin has simply been ignored, especially by his cultured despisers. Marilynne Robinson, the Pulitzer Prize—winning novelist (Gilead) who has tried to rescue Calvin from his detractors, reports that she has "encountered an odd sort of social pressure as often as I have mentioned him. One does not read Calvin. One does not think of reading him … Calvin seems to be neglected on principle."

There is evidence, however, that Calvin is making a comeback. This past year has seen numerous conferences, lectures, and publications evaluating Calvin and his role as one of the most consequential thinkers of the last millennium. A few months ago, Time magazine published a story on the top ten forces that are currently changing the world. In addition to expected trends like the increasing role of the Internet and the global financial crisis, the renaissance of Calvinism in America came in as number three on the list. The evangelical blogs are abuzz, and Twitter is atweet, with comments on free will and predestination, original sin and sovereign grace.

Last year at Beeson Divinity School, two of our finest professors were cajoled (somewhat against their will, I think) by the students into a public debate on limited atonement. Even the David Crowder Band has a lyric, "I am full of earth / you are heaven's worth / I am stained with dirt / prone to depravity." And U2's 2009 album, No Line on the Horizon, chimes in with, "I was born to sing for you / I didn't have a choice but to lift you up," with the refrain, "Justified until we die / you and I will magnify / the Magnificent." Who knew that Bono was at least a three-point Calvinist?

Still, the question remains: Why does Calvin persist as such a controversial—and monumental—figure in the Christian story? Why does he still generate such contrary emotions? What has kept Calvin from fading into the shadows of church history?

Late Bloomer

Calvin was a second-generation reformer. He was born on July 10, 1509, in Noyon, France, 50 miles northeast of Paris, and was barely eight years old when Luther posted his 95 theses on the castle church door at Wittenberg. The son of a church official in the cathedral city of Noyon, Calvin seemed destined for a priestly career. His father pulled strings to acquire a benefice for him to continue his education in Paris, at a school Erasmus had also attended a few decades earlier. But his father suddenly changed his mind midcourse and sent Calvin to study law, first at Orléans and then at Bourges. Remember that Luther, in defiance of his father, gave up the study of law to become a monk, whereas Calvin, in obedience to his father, left the study of theology to become a lawyer.

When Calvin joined the Protestant cause in the early 1530s, the Reformation seemed to be falling apart. The Peasants' War and the bloody debacle in the city of Münster discredited Anabaptism (unfairly) as a force for constructive reform. In 1525 Erasmus and Luther famously quarreled over the bondage of the will, driving a wedge between humanism and the reform movement coming from Wittenberg. Luther and Zwingli bitterly quarreled over the Lord's Supper at the Colloquy of Marburg in 1529. When Zwingli died on the battlefield two years later, Luther thought it a well-merited end for such a heretic. At this precise moment, with Zwingli dead and Erasmus dying, with Luther quiescent (if not quiet!), with the Roman Church resurgent and the Radical Reformation fragmented, John Calvin emerged as the leader of a new movement and the reformulator of a new theology.

His training in law had introduced him to the serious study of ancient texts. He gave himself to the study of the "new learning" advanced by Erasmus and other scholars who followed the Renaissance principle ad fontes ("back to the sources!"). In 1532 he published a commentary on De Clementia, a treatise by the Roman philosopher Seneca. At home with the classical past and the world of ideas, Calvin could well have spent his life as a man of letters devoted to the literary arts. Then, as he later put it, "by a sudden conversion (subita conversio) God turned my heart and made it teachable."

Calvin once confessed, "I don't like to talk about myself," and in fact he says next to nothing about the circumstances of his conversion. Was this the prototype of an evangelical revival experience, as in the old gospel song that proclaims, "I can tell you now the time, I can take you to the place, where the Lord saved me by his marvelous grace"? Some followers of Calvin, such as Ruth Bell Graham, have been sure of their faith, but could not remember the date or time when they first trusted in Christ. If Calvin had such a datable conversion, he must have kept it to himself. However, he did refer to Paul's conversion in a similar way to his own: "This sudden and unhoped-for change shows that he was compelled by heavenly authority to affirm a doctrine that he had assailed."

Perhaps by "sudden conversion" Calvin meant not so much a lightning-quick occurrence as a sense of being completely overwhelmed by God's grace. Calvin had no illusions that he would ever have drifted into a proper relationship with God apart from the prevenient turning on God's part. Such an event might well be deeply personal and moving, but what impressed Calvin most was the divine agency of the Holy Spirit, who had brought it about in the first place.

Ministry 'On the Boundary'

Calvin was not only a reformer of the second generation; he was also a reformer of the second occupation. In 1536, he published at Basel the first edition of what would become his masterpiece, the Institutes of the Christian Religion. His desire was to edify the church by his quiet study and writing. "The summit of my wishes," he later wrote, "was the enjoyment of literary ease, with something of a free and honorable station." Just give me a carrel in the library, and let the rest of the world go by! But these plans were soon turned upside down when he was forced to take a detour through Geneva, where he encountered the fiery French preacher Guillaume Farel.

Geneva was a city of some 10,000 inhabitants and had recently expelled the Catholic bishop and embraced the reform. Now Farel implored Calvin to stay in Geneva and help him build up the church there. When Calvin demurred, Farel "suddenly set all his efforts at keeping me," Calvin recalled. Farel thundered God's judgment against Calvin.

"So God thrust me into the game," Calvin said. Again, suddenly, God's direction came in an unexpected way.

Apart from a three-year exile in Strasbourg (1538—41), Calvin served as "a minister of the divine Word" in Geneva for 28 years. Biographer Bernard Cottret has pointed out that Geneva was a frontier city, squeezed between France, the Swiss cantons, and the Duchy of Savoy. In the 16th century Geneva began to attract the international reputation it enjoys today, as thousands of "immigrants" flocked there from persecutions in France, Italy, England, and parts of Germany.

Calvin's ministry was thus developed "on the boundary," to use Paul Tillich's phrase. Calvin himself was a refugee and always looked with longing toward his native France. (The first mention of Calvin in the registers of Geneva referred to him as ille Gallus, "that Frenchman"!) A sense of displacement and homelessness underlay his difficult dealings with the local authorities in the city.

Yet his role as an outsider on the inside gave him a special appeal to the "company of strangers" who crowded into the Cathedral of St. Pierre to hear his sermons. Theodore Beza reported in 1561 that more than one thousand persons were coming to hear Calvin expound the Scriptures every day. Calvin was a preacher of enormous vitality, and his sermons bristled with piercing application as well as exegetical insight. He was not afraid to speak truth to power, and on one occasion referred to Genevan officials as "gargoyle monkeys" who had become so proud that "they vomit forth their blasphemies as supreme decrees."

A Churchly Reformer

Calvin was not only a teacher of the Word but also a master of words. In addition to his Institutes, which went through eight revisions in his lifetime and was soon translated into all the major languages of Europe (Thomas Norton's English version had gone through 11 editions by 1632), there were his published sermons, letters, treatises, catechisms, psalm books, liturgies, and, most importantly, his commentaries on nearly every book of the Bible. Geneva became the center of a thriving publishing trade that spawned a network of clandestine colporteurs, book smugglers who took Bibles and religious tracts into every corner of Europe.

The most remarkable thing about Calvin's theology is how unremarkable it is, especially when set against the Catholic, Augustinian, and Lutheran traditions he inherited, reframed, and passed on to others. In retrospect, Calvin stands out next to Luther as one of the two great shaping theologians of the Protestant movement. But we should not detach him from other seminal thinkers with whom he shared certain basic assumptions about God, the Bible, human beings, and the work of Christ in the world. Martin Bucer in Strasbourg, Heinrich Bullinger in Zurich, Johannes Oecolampadius in Basel, Peter Martyr Vermigli from Italy, and Luther's successor, Philip Melanchthon, were all Calvin's friends and colleagues in the work of reform.

Unlike the Anabaptists, who sought a New Testament church unencumbered by the baggage of history, Calvin and his peers wanted to be nothing more than faithful and obedient members of the one, holy, catholic, and apostolic church. This church, they believed, had fallen into disrepair. It had been led into captivity by the Roman Catholic hierarchy. Yet there were points of continuity as well as discontinuity with the Catholic past, and the church needed to be reformed on the basis of the Word of God. Catholic historian Alexandre Ganoczy has said of Calvin: "He never stopped claiming his unshakable attachment to the unity of the Catholic Church, which he did not want to replace, but to restore."

'Preforeordestination'

Mark Twain has Huckleberry Finn refer to a perplexing Calvinist sermon he once heard on "preforeordestination." In agreement with Augustine, Thomas Aquinas, and Luther before him, Calvin did teach that God was sovereign in salvation no less than in creation, and that divine election was entirely gratuitous—ante praevisa merita, as the scholastic tag went, not based on God's foreknowledge of human achievement. Calvin held this view not because he was a mean man or a dour despot, but because he believed to have found it clearly taught in Holy Scripture. For Calvin, however, the doctrine of predestination was not an a priori metaphysical axiom from which everything else was derived. Rather, it had a Christological focus (with Christ as the mirror of election) and a pastoral import.

In discussing predestination, Calvin followed the method of Paul in his Epistle to the Romans. One does not begin with the inscrutable decrees of God, but rather with God's general revelation in creation and the conscience (Rom. 1). This leads to a discussion of human sinfulness (chapters 2-3), God's atoning work in Christ and justification by faith (chapters 4-7), followed by the pouring out of the Holy Spirit and the declaration of God's unfathomable love (chapter 8). Only then is it fitting to consider the theme of God's electing grace in the history of Israel and in our own lives (chapters 9-11). Only then, as we look back on our rescue from sin, can we exclaim with the non-Calvinist Charles Wesley, "Amazing love, how can it be, that thou my God shouldst die for me!"

The elect are not the elite. There is no place in Calvin's thought for the kind of spiritual snobbery reflected in the old camp-meeting ditty, "We are the Lord's elected few, / let all the rest be damned./ There's room enough in hell for you, / we don't want heaven crammed!" The true Calvinist preaches the gospel promiscuously to all persons everywhere, aware that God alone infallibly knows all those who belong to him.

Theology for Trekkers

In Calvin's day, Geneva became a great center for church planting, evangelism, and even "foreign" missions: a group of Protestants supported by Admiral de Coligny carried the message of Christ to the far shores of Brazil in 1557, more than 60 years before the Pilgrims landed at Plymouth Rock. William Carey, the father of modern missions in the 18th century, went to India with a Calvinist vision of a full-sized God—eternal, transcendent, holy, filled with compassion, sovereignly working by his Holy Spirit to call unto himself a people from every nation, tribe, and language group on earth.

In Book Three of the Institutes, Calvin treats predestination and prayer in contiguous chapters (Institutes3.20-21). The universal appeal of Calvin's thought is expressed clearly in this petition he prepared for his liturgy "The Form of Prayers":

We pray you now, O most gracious God and merciful father, for all people everywhere. As it is your will to be acknowledged as the Savior of the whole world, through the redemption wrought by your son Jesus Christ, grant that those who are still estranged from the knowledge of him, being in the darkness and captivity of error and ignorance, may be brought by the illumination of your Holy Spirit and the preaching of your Gospel to the right way of salvation, which is to know you, the only true God, and Jesus Christ whom you have sent (John 17:3).

One of the mysteries of the mystique of Calvinism is how such a high predestinarian theology could motivate so many of its adherents to such intense this-worldly activism. Calvinism was certainly a dynamic force in shaping the contours of the modern world, including features of it that most of us would not want to live without, such as the rule of law, the limitation of state power, and a democratic approach to civil governance. Though Max Weber was off the mark in identifying the "spirit of capitalism" with the Puritan desire to find assurance of election in a joyless acquisitiveness, he was right to point to the importance of Calvinist ideals—thrift, hard work, fair play, personal responsibility—in the development of a robust economic system.

Calvin's theology was meant for trekkers, not for settlers, as historian Heiko Oberman put it. In the 16th century, Calvinist trekkers fanned out across Europe initiating political change as well as church reform from Holland to Hungary, from the Palatinate to Poland, from Lithuania to Scotland, England, and eventually to New England. In its drive and passion, in its world-transforming vision, Calvinism was an international fraternity comparable only to the Society of Jesus in the era of the Reformation. It is perhaps ironic that Calvin and Ignatius Loyola studied at the same time in the same school in Paris.

Like the Franciscans and the Dominicans in the Middle Ages, Calvin's followers forsook the religious ideal of stabilitas for an aggressive mobilitas. They poured into the cities, universities, and market squares of Europe as publishers, educators, entrepreneurs, and evangelists. Though he had his doubts about predestination, John Wesley once said that his theology came within a "hair's breadth" of Calvinism. He was an heir to Calvin's tradition when he exclaimed, "The world is my parish."

And so was the Baptist Walter Rauchenbusch in his concern for the social gospel, which (as Rauchenbusch used the term) did not mean another gospel separate from the one and only gospel of Jesus Christ. It simply meant that that gospel must not be sequestered into some religious ghetto but taken into the real ghettos and barrios of our world.

With only slight exaggeration, we can say that while the Anabaptists rejected the world as a realm of darkness to be shunned, and Luther accepted the world as a necessary evil, Calvin sought to overcome the world, to transform and reform the world on the basis of the Word of God. This world in all of its squalor and sin is nonetheless the "theater of God's glory."

Complex, Inconsistent

One reason that Calvin's legacy is ambiguous is that his thought is complex and sometimes inconsistent. For example, in his commentary on Romans 13, Calvin urges obedience even to wicked and unjust rulers whose tyranny may be "the Lord's scourge to punish the sins of the people." But elsewhere he allows resistance to such rulers if it is led by "lesser magistrates" with duly constituted authority. Acting on this principle, followers of Calvin sought to replace the Catholic monarchs of France with Protestant princes, led a revolt in the Netherlands against Philip II of Spain, and, in 1649, chopped off the head of Charles I, the duly anointed king of England. As historian William Bouwsma said, Calvin was a revolutionary in spite of himself.

Likewise, while Calvin strongly defended private property, he was also concerned about social justice for the poor. He turned the office of deacon in Geneva into a ministry of mercy and opposed exorbitant rates of interest and other abuses that pinched the poor.

Calvin also set forth a complex theory of Christian liberty that helped provide a basis for legal protections of freedom of conscience and the free exercise of religion. He spoke about "the rights of our common human nature," rights granted by the sovereign God to all persons made in his image. However, his commitment to liberty and his opposition to tyranny did not prevent him from acquiescing in the death of Michael Servetus, who was executed in 1553 for calling God a three-headed monster. Calvin's fear of anarchy and his dread of heresy came together in the fate of Servetus.

Calvin and his ideas have had a shaping role in American history, one that goes far beyond matters of church polity and religious doctrine. From Jonathan Edwards to William Faulkner, American writers have worked within an intellectual framework marked by beliefs and attitudes shaped by Calvin's Institutes and the Geneva Bible, both of which came to America with the Pilgrims on the Mayflower. Yet this Calvinist heritage is not straightforward at all.

Calvin emphasized the sacredness of human life and the capacity of human beings made in the image of God to think, to know, and to act with nobility. Ralph Waldo Emerson, the grandson of Puritans, picked up on this theme and expanded it into a kind of cosmic optimism, declaring in his 1838 Harvard Divinity School address, "If a man is at heart just, then insofar is he God." Emerson and the Transcendentalists who joined his cause sang a rhapsody to the unsullied soul; they wanted Genesis 1 without Genesis 3, the Creation without the Fall. This is the root of all utopian politics and perfectionist theology.

But the deeper channel of Calvinist influence has emphasized the tragic sense of life, rooted in a skepticism about unredeemed human nature and its capacities for self-deception and self-justification. As the character Willie Stark says in Robert Penn Warren's All the King's Men, "Man is conceived in sin and born in corruption and he passeth from the stink of the didie to the stench of the shroud." This understanding of human sinfulness is quite different from the "God's in his heaven, all's right with the world" philosophy of positive thinking.

But according to Calvin, only by seeing ourselves as we really are, in our utter perversity and alienation, can we enter fully into salvation's benefits. A serious doctrine of original sin calls for a radical doctrine of redemptive grace. This dialectic of sin and grace also excludes any notion of boasting, as Paul repeatedly said. There is no place for priggishness in a Calvinist worldview, no pitting of us "good guys" against "all them others." The verse that Augustine found so helpful in his struggle against the Pelagians is also essential for a Calvinist understanding of the self: "For who makes you different from anyone else? What do you have that you did not receive? And if you did receive it, why do you boast as though you did not?" (1 Cor. 4:7).

Calvinism Reborn

These things are not new, but they are getting a new hearing among Christians today. According to a recent survey, some 30 percent of recent graduates from seminaries affiliated with the Southern Baptist Convention, America's largest Protestant denomination, identify themselves as Calvinists.

In 2009, there are more writings in print by 19th-century Calvinist pastor Charles Haddon Spurgeon than by any other English-speaking author living or dead. Among those reading Spurgeon, as well as the writings of J. I. Packer, John Piper, and R. C. Sproul, are thousands of young Christians who flock to the Passion and Together for the Gospel conferences, hundreds of pastors who have planted churches affiliated with the growing interdenominational Acts 29 movement, and charismatic Calvinists who resonate with C. J. Mahaney, Joshua Harris, and the Sovereign Grace churches.

And they are also reading younger Calvinist writers such as Collin Hansen, whose Young, Restless, and Reformed chronicled this resurgence (first in a Christianity Today article and then at book length), and Christian George, whose Godology is a theological primer for 20-somethings. To this must be added the culture-shaping influence of Tim Keller, a Presbyterian Church in America pastor in New York City, and a cadre of Reformed-rooted academics including Alvin Plantinga and George Marsden whose writings have been a major force in the disciplines of philosophy and history.

Calvin's ideas are getting traction for at least three reasons.

First, postmodernity has placed us all "on the boundary"—on the border between the fading certainties of modernism and new ways of understanding the world and its promises and perils. Calvin, a displaced refugee, speaks directly to the homeless mind of many contemporaries looking for a place to stand. "We are always on the road," Calvin wrote. Like Augustine, Calvin reminds us that our true homeland, our ultimate patria, is that city with foundations that God is preparing for all who know and love him. In the meantime, believers are "just sojourners on this earth so that with hope and patience they strive toward a better life."

Second, while Calvin is often depicted as an intellectualist and theological rationalist, in fact his theology is pervaded by mystery. No less than Luther, Calvin recognized the supreme paradox of the Word made flesh. He is a theologian of both/and, not either/or: divine sovereignty and human responsibility, written Word and living Spirit, the church invisible and the church congregational, already and not yet. Calvinists are willing to live with tension and even antinomy in this world, seeing through a glass darkly in the hope of the glory that shall be revealed. This is what it means to live faithfully in a broken world, one still yearning for full redemption.

The late theologian Elizabeth Achtemeier sums up the quiet confidence and deep joy that comes from the Calvinist way of faith: "The Christian way of life is no fairytale; in the power of the Spirit, it can be lived. Countless Christians through the ages have shown us how. The fruit of worship and Bible study and prayer and obedience to the Word, is a joy, a peace, an unshakable hope that the world cannot give or take away."

Finally, Calvin was a theologian of the long view. When he died in 1564, it was by no means certain that the Reformation would triumph even in Geneva. As committed as Calvin was to the hardheaded practicalities of life in a real world ever marked by struggle, he took his stand in the light of eternity undeterred by the vicissitudes of history. He believed, as did the Anglican-turned-Catholic John Henry Newman, that Jesus was victor and that at the Last Day God would save his people "in the intervals of sunshine between storm and storm … snatching them from the surge of evil, even when the waters rage most furiously."

When visiting Geneva today, one is shown the imposing Monument of the Reformation, where Calvin stands in stone, larger than life, flanked on either side by statues of famous reformers and statesmen. Somehow this monument, impressive as it is, seems out of character for the man it was built to commemorate. Calvin did not seek his own glory but died confessing, "All I have done is of no worth…I am a miserable creature." At his request, he was buried in a common cemetery, with no stone erected over the site of his interment. His life's goal was to be a faithful servant of the Word of God. The light that emanates from his witness still shines—post tenebras lux ("after the darkness, light," the motto of the Genevan Reformation)—pointing men and women toward the adoration of the true God, whose glory is revealed in the face of Jesus Christ.

Timothy George is the founding dean of Beeson Divinity School of Samford University and a senior editor of Christianity Today. He also serves as the general editor of the Reformation Commentary on Scripture, a 28-volume work of 16th-century biblical comment forthcoming from InterVarsity Press. Download a companion Bible study for this article at ChristianBibleStudies.com.

Copyright © 2009 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere:

See also today's related articles, "The Reluctant Reformer: Calvin would have preferred the library carrel to the pulpit" and "Calvin's Biggest Mistake: Why he assented to the execution of Michael Servetus."

Tomorrow: What Calvin Gets Right: Even those who vigorously disagree with the Reformer are still impressed.

Timothy George also recently wrote "What Baptists Can Learn From Calvin" for Christian History.

More on Calvin is available at our special section on the reformer.