Sometimes a little book can make a big difference in how people think about right and wrong.

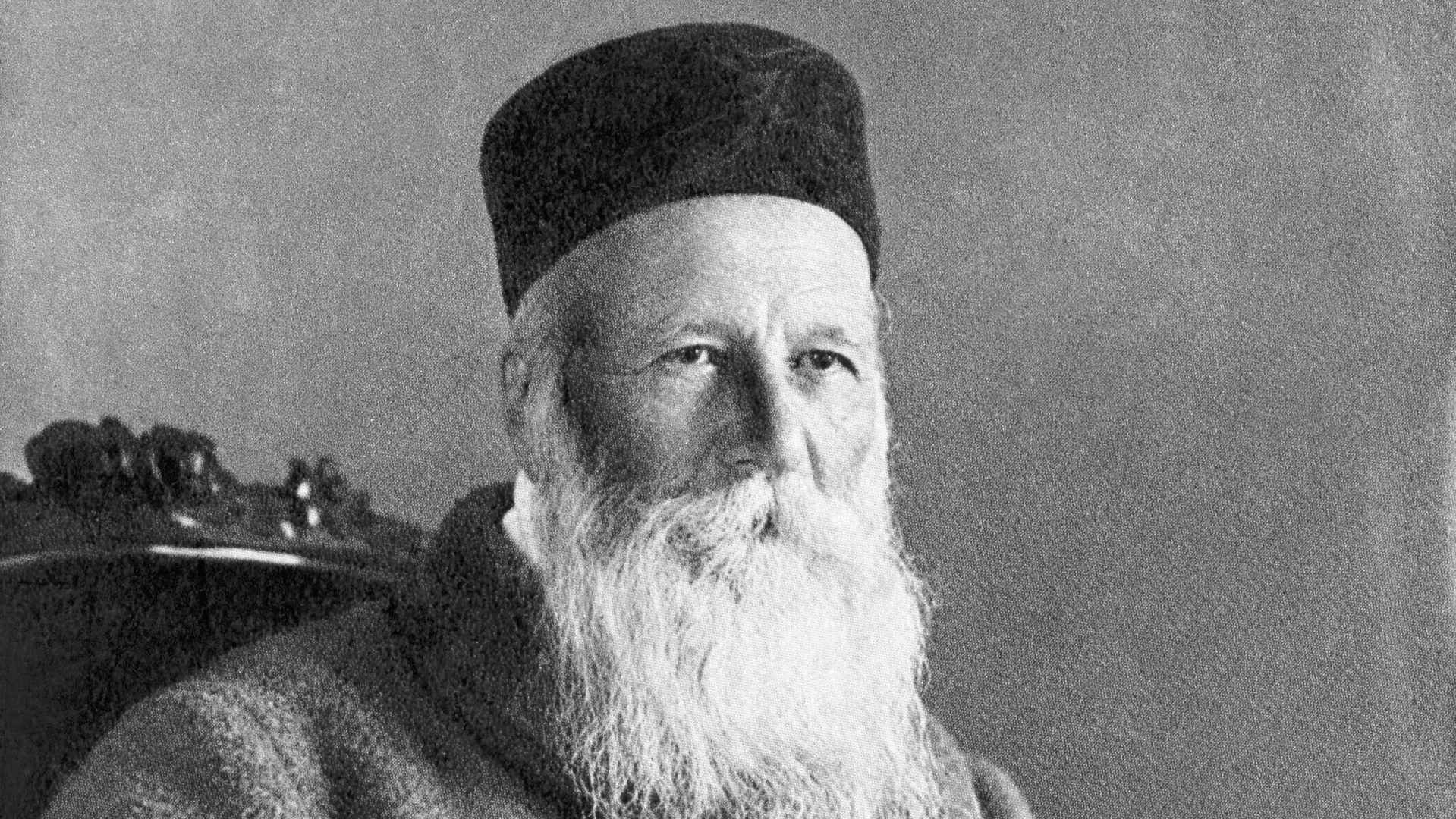

Harriet Beecher Stowe’s 1852 novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, profoundly affected the way white Americans perceived slavery. Ten years later and across the Atlantic, Henry Dunant published another revolutionary book, A Memory of Solferino: his eyewitness account of the aftermath of one of Europe’s bloodiest battles.

Dunant’s book is rarely read today. But if you are outraged when bombs, rockets, or artillery shells fall on hospitals, schools, and places of worship, you can trace that presumption—that these should be safe places—to Dunant.

Before Solferino, treating the wounded was an afterthought. Henry Dunant proposed forming an international organization to field medical personnel and supplies in wartime.

Dunant was a Swiss investor working in Algeria. He had been unable to get land and water rights from the colonial authorities, so he appealed directly to the French emperor, Napoleon III.

But the emperor was trying to liberate northern Italy from Austrian domination. When Dunant arrived in Solferino, Napoleon’s headquarters, the landscape was littered with dead, dying, and wounded soldiers. Surprised by the scale, the two armies were completely unprepared to bury their dead, comfort the dying, or tend the wounded. Their field hospitals and medical supplies were woefully inadequate. Compassion for wounded enemies was also in short supply: both armies shot or bayoneted them.

Dunant was a natural organizer. As a teenager, he formed a Bible study group that worked for the poor. At age 22, he founded the Geneva chapter of the Young Men’s Christian Union (parallel to the English and American ymca). When some planned to create a federation of European Ys, he argued instead for an international ymcafederation. So, at age 25, he went to Paris to represent Geneva at the first international YMCA convocation.

Dunant used his organizational gifts at Solferino. He commandeered the biggest church in a nearby village, arranged the wounded for maximum efficiency, purchased a large shipment of linen for bandages, and persuaded local women to care for the injured. He even inspired them to set aside their hatred of the enemy. Tutti fratelli (“All are brothers”) became their motto.

But if you were going to treat the wounded and alleviate their pain, Dunant knew, you needed to protect medical personnel, chaplains, and field hospitals. Before Solferino, medics were considered partisans. Dunant proposed that opposing armies consider medics neutral and treat medical facilities as safe zones. Before Solferino, no one would help wounded enemies for fear that they were merely posing as wounded in order to stab anyone who came near. Dunant believed that medics should help the wounded regardless of their side in the battle. Before Solferino, treating the wounded was an afterthought. Dunant proposed forming an international organization to field medical personnel and supplies in wartime.In his 1864 Letter to Atlanta, General William Tecumseh Sherman wrote, “War is cruelty, and you cannot refine it.” Dunant disagreed. He believed war could and should be made more humane.

Today, 196 nations subscribe to the Geneva Convention. The Red Cross is internationally active not only in war-related emergencies but also in natural disasters.

Dunant’s book stirred popular enthusiasm. In 1863, just a year after he published it, he and four friends convened official representatives from 16 nations, who agreed on the key points of Dunant’s vision. (Inspired by the Emancipation Proclamation, he asked President Lincoln to send a representative. Lincoln, feeling his political position was precarious, sent an observer instead.) The next year they met again and formally drafted the Geneva Convention for the Alleviation of the Condition of the Wounded in Armies in the Field. For their symbol, they adopted a red cross on a white background.

Today, 196 nations subscribe to the Geneva Convention and its later elaborations. The Red Cross and parallel organizations (Red Crescent and Magen David Adom) are internationally active not only in war-related emergencies but also in natural disasters.

Dunant was more successful as a social visionary than as a businessman. In 1867, he lost his fortune and went bankrupt. It was not until 1895 that a journalist vacationing in the Alps discovered Dunant living in a senior hostel. The journalist brought Dunant back to public attention, and in 1901, the first ever Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to this Christian visionary.

We can easily call the four Geneva Conventions the Dunant revolution. They have multiplied the list of wartime taboos. Dunant understood that all wars are great human tragedies. He hoped that by tending all the wounded and dying, friend and foe alike, the nations would learn the truth discovered at Solferino: Tutti fratelli. We are all one family.

David Neff is the former editor in chief of Christianity Today.