If you want to measure the global acclaim of the current pope, ask 100 random people about the Roman Catholic Church. While you will see a few thumbs up, most will express ambivalence bordering on dislike or distrust. Some will be hostile. Ask them about Pope Francis I, however, and the responses will be overwhelmingly positive. The Jesuit from Buenos Aires pleases many and brings smiles to their faces.

He even made Luca Baratto smile. Baratto, a pastor in the Federation of Evangelical Churches in Italy, heard Pope Francis apologize for the Catholic Church’s complicity in the Italian government’s persecution of Pentecostals and evangelicals during the 1920s and ’30s. Baratto was surprised too: Francis’s apology was unscripted and unannounced beforehand. That is his style, at once unpredictable and committed to breaking down the often-bitter rivalry between evangelicals and Catholics.

Bergoglio was elected in large part because he was a Vatican outsider. This gave the cardinals hope that he could successfully reform the curia, the Catholic Church’s ineffective—and in some cases criminally corrupt—bureaucracy in Rome.

The Jesuits carry the reputation of clerical commandos. In the US Army, a Green Beret can’t rise above the rank of colonel. That’s because men trained to freelance as fighters aren’t likely to fit well in the command-and-control system of the Army. The Catholic Church has drawn a similar conclusion about the order that Ignatius of Loyola founded in 1534. What makes for creative and effective witness on the frontiers of Christianity usually isn’t what’s needed for the daily running of the institutional church. Jorge Mario Bergoglio’s 2013 election was unexpected as well. The first pope from the Southern Hemisphere, he is also the first Jesuit pope, even though the Society of Jesus discourages its members from holding high office.

When the cardinals gathered to choose a successor for Pope Benedict XVI (Joseph Ratzinger of Germany), they thought otherwise about Catholicism’s needs. Bergoglio was elected in large part because he was a Vatican outsider. This gave the cardinals hope that he could successfully reform the curia, the Catholic Church’s ineffective—and in some cases criminally corrupt—bureaucracy in Rome.

The impotency of the curia has been a problem for decades. At the Second Vatican Council, the Catholic Church adopted a much more biblical approach, transforming its worship and fundamentally changing its relation to modern secular culture. What did not change was the church’s bureaucratic structure, as well as the largely Italian and incestuous culture within said bureaucracy, perhaps a more significant problem.

The curia’s dysfunctions were not addressed by John Paul II and only tentatively so by Benedict XVI. Indeed, some say Benedict resigned in 2013 because he knew he couldn’t implement curial reform with enough gusto, determination, and (to be frank) ruthlessness to succeed. Pope Francis, by contrast, has established an eight-cardinal advisory council that operates independent of the existing bureaucracy. This important work of reform will not make headline news, but it bids fair to reshape Catholicism’s institutional identity, making Rome more international and responsive to the challenges facing global Christianity.

Evangelical Protestants, who today find themselves aligned with Catholics on many cultural issues—especially issues of life, marriage, and human sexuality—can welcome these reform efforts. In fact, they need a healthy Catholic Church as an ally. As we see a secular vision of morality and civic life grow aggressive and hostile, we are going to need each other.

Vicar Without Guile

It’s fair to say, however, that what made the reforming Bergoglio attractive to the cardinals comes with some problems. His often-unscripted statements since his election have given many Catholic leaders heartburn. His famous “Who am I to judge?” response to a question about homosexuality, while entirely in keeping with Matthew 7:1, has been used by progressive US Catholics to blunt or silence the church’s witness on marriage and human sexuality. Most recently, the summary deliberation statements from the Vatican’s Synod on the Family have led media to describe Francis as “shifting” or “evolving” on issues of homosexuality and marriage.

The media’s response is to be expected. Lacking a deep understanding of Catholic teaching, the press tends to see the world in the right/left framework of American politics. In this framework, a reformer is always a progressive. In an extensive interview published in Jesuit journals worldwide, Francis expressed dismay over “small-minded rules,” chastised a certain kind of conservative mentality, and observed that the Catholic Church needs to move down “new roads” and “new paths.” Of hot-button moral topics, he said, “We cannot insist only on issues related to abortion, gay marriage, and the use of contraceptive methods.”

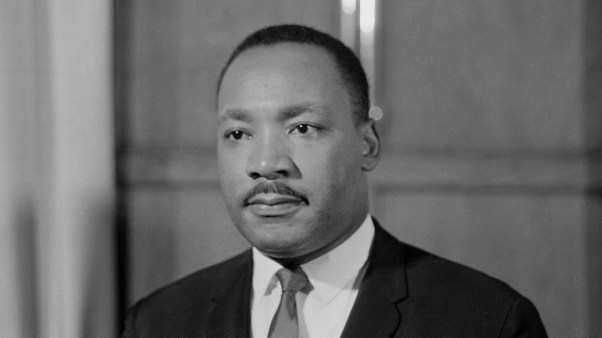

The editorial page of The New York Times, so often preoccupied with sexual liberation, exults over such statements, believing, The Catholic Church is finally joining the company of the Enlightened! What the press generally fails to see is historical context. All the great reform movements of Christianity have called the church universal back to the fundamental truths of the gospel. Martin Luther was many things, but never a progressive. In the case of Francis, the media does not realize that his statements are more pastoral than doctrinal in nature. He wants to reframe the classic doctrine and morals of the Catholic Church so that a secular world can be converted and adhere to them.

His namesake, Francis of Assisi, remains a central archetype in the Western spiritual imagination. When we see Francis’s witness renewed, as Pope Francis has done in a number of ways, many of us swoon.

There are other reasons for Francis’s popularity, however, ones truer to who he really is and what he represents. He speaks spontaneously, with directness, pungency, and openness—a striking contrast to our political leaders and their poll-tested stances “messaged” with 24/7 spin. Francis, by contrast, is not conducting a political campaign. He’s not trying to win a popularity contest, nor is he angling to become a celebrity—all of which we find refreshing because it is so rare among public figures.

Important as these qualities may be, there’s a deeper reason why so many thrill to the new pope. His namesake, Francis of Assisi, was and remains a central archetype in the Western spiritual imagination. He embodied the discipleship of the New Testament and made the gospel a living reality more than 1,000 years after the apostolic age, showing us a way to do so today. When we see Francis’s witness renewed, as Pope Francis has done in a number of ways, many of us swoon.

The Way of Poverty

Bonaventure, the great 13th-century scholar and head of the Franciscan order, wrote The Life of Saint Francis of Assisi. His purpose was evangelical: to bring readers to encounter Francis as a “herald of gospel perfection.” Bonaventure wanted us to follow the way of Francis, which is the way of poverty and the way of literalism.

Francis “owns,” as it were, the biblical motif of poverty. A lover of “holy poverty,” he embraced “sublime poverty,” the so-called queen of the virtues. “None was ever so greedy of gold as he of poverty,” wrote Bonaventure, “nor did any man ever guard treasure more anxiously than he this gospel pearl.”

Bonaventure gives an extensive catalog of Francis’s ever-renewed commitment to poverty. A particularly colorful episode involves an incident on the road when Francis refused to pick up a purse full of coins that his brethren wished to give to the poor, correctly seeing it as a snare of the Devil. In another instance, he is invited to dine with bishops but begs crusts of bread before the meal.

The way of poverty is arresting in part because it’s a spiritual ideal we can realize in an instant. Poverty requires no resources, no talents, no achievements, no status, no family connections.

In these and other stories in Bonaventure’s biography of Assisi, we learn that poverty is the surest path to God. Neither the church of his time nor that of later centuries made Assisi’s example of poverty mandatory, but his witness has always been cherished. That’s because Francis of Assisi teaches us a powerful truth: If we possess nothing, then nothing will get in the way of being possessed by Christ.

The way of poverty is arresting in part because it’s a spiritual ideal we can realize in an instant. Poverty requires no resources, no talents, no achievements, no status, no family connections. Anyone can wed himself to Lady Poverty. Nothing stands in the way—except, of course, our unwillingness to travel the path of renunciation. And because Christ chose the path of poverty, to say that poverty is immediately accessible is to say that a deep conformity to Christ is immediately accessible.

As Paul puts it in his Letter to the Romans (paraphrasing somewhat), we don’t need to wait around for the right set of dogmas to be defined or spiritual disciplines to be fine-tuned. No, as Moses teaches, “The word is very near you; it is in your mouth and in your heart so you may obey it” (Deut. 30:14).

The immediate possibility of poverty is closely connected to the second Franciscan virtue, literalism. The saint’s spiritual imagination is no more richly adorned than his humble hermitages. Just as Francis of Assisi stripped off life’s softening luxuries, he also removed anything that might soften the Word of God. His commitment to poverty stemmed from directly applying the teachings of Jesus to his life: “Do not get any gold or silver or copper to take with you in your belts—no bag for the journey or extra shirt or sandals or a staff” (Matt. 10:9–10).

A similar literalism characterized Francis’s response to a voice speaking to him from the cross of Christ when he was praying in the dilapidated Church of San Damiano in Assisi. The voice said, “Go and repair my house.” So he set about to raise funds, triggering the confrontation with his father that led to his disinheritance and allowed him to enter into the divine inheritance of poverty. Indeed, Francis’s bullheaded literalism brought him to an almost absurd state. Stripped of all resources, he was reduced to carrying uncut stones to the church to contribute to its rebuilding.

It’s easy for many of us today to mock literalism as a plank in the fundamentalist platform. But this is a mistake, for literalism encourages a disposition to the Word of God that prevents us from hiding in a self-generated fog.

Some years ago, I was with an academic friend, a game theorist with a skeptical mind who is also a conservative Protestant. As he explained his work with a prison ministry in Texas, I found myself surprised and asked why he was involved. He said, “More than a decade ago, I realized that when Jesus tells us to feed the hungry, cloth the naked, and visit the prisoner, he actually means it.”

The literalism of Francis is like that of my friend—it makes immediate the commands of God. The same goes for his spiritual imagination more broadly. Francis did not have a conceptual mind. He did not think in terms of kenosis or the “metaphysics of gift” or the notion of “cruciform existence.” Instead, he interpreted what it means to be Christlike in a literal way, which means in a this-worldly, applies-to-me way.

When Jesus tells the rich young man that he must sell all his possessions and give the money to the poor, the immediacy of literalism and poverty come together. There is no ambiguity about the command and no impediment whatsoever to its being obeyed—no impediment except for our ongoing acquiescence to, and even affirmation of, our bondage to sin and death. Moreover, we must remember why Jesus commends the way of poverty to the rich young man. It is for the sake of perfection, which means the holiness of life in God.

By my reading of our Western tradition, both Protestant and Catholic, a literal conformity to Christ has become our spiritual ideal. That has expressed itself in some simplistic ways, with WWJD bracelets or championing a “red-letter Jesus” or pursuing a “radical” faith. But the deeper yearning reflects a sound spiritual response, a desire to be conformed to Christ. Instead of the icon of Christ Pantocrator (which is a central image for Christians in the East), in the West, we fix upon what Bonaventure described as the “luminous darkness” of the Cross.

There is a similar luminous darkness in the joy of poverty that marks Francis’s Cross-centered life. For this reason, the begging friar in his rude habit serves as an indispensable aide to contemplation. Many are bewitched by Francis of Assisi because in him we see the face of Christ.

A Servant, Not a Prince

There’s little doubt that Pope Francis’s background in Argentina has shaped his views. He entered the Society of Jesus as a young man, served as head of the Jesuits in Argentina during the brutal civil strife of the 1970s, was appointed archbishop of Buenos Aires in 1998, and made a cardinal by John Paul II in 2001. Throughout his ministry, he has dealt with a political form of Catholic conservatism closely allied to repressive authoritarianism, something that explains his occasional sharp rebukes that bring the media such joy. Moreover, Argentina remains a deeply troubled country with a failed economy, which contributes to Francis’s obvious antipathy to ideologies that make a god of free markets.

The name the pope has chosen indicates that he wishes his pontificate to draw upon the spiritual power of that great hero of the faith to strengthen the church’s witness to Christ.

But this background and his episodic outbursts will not be the most important distinctions about the pontificate of the Argentine Jesuit, who is the first pope to have taken Francis of Assisi’s name. Nor will it be his efforts to reform the church’s bureaucracy, a necessary but Sisyphean labor that admits of only partial success. Instead, it’s the Franciscan dimension—which is to say the evangelical dimension. The name the pope has chosen indicates that he wishes his pontificate to draw upon the spiritual power of that great hero of the faith to strengthen the church’s witness to Christ.

The pope consistently offers himself as a servant, not a prince. This has been the trajectory of the papacy over the past generation or two. John XXIII refused to be carried on the papal throne. John Paul I refused the papal crown. But Pope Francis’s renunciations are more emphatic. It was much reported that as archbishop of Buenos Aires, he took the bus to work. Since his election, he has refused the papal apartment and red leather shoes.

These decisions are symbolic, of course, but symbols matter. A Protestant friend told me about a recent meeting he attended in Rome. His hosts had arranged a meeting with the pope during which Francis asked the group of academics to pray for him. My friend, moved by the pope’s plea, grasped the mendicant spirit of the request.

Pope Francis echoes Francis of Assisi’s literalism. I can’t imagine him embarking on a series of sermons as intellectually ambitious as John Paul II’s theology of the body. Nor can I see him writing theologically rich and evocative encyclicals, as did Benedict XVI. His preaching is unadorned, and Evangelii Gaudium, his recent apostolic exhortation, is straightforward: Greed is bad. There are no throwaway people. Every Christian is an evangelist. Pope Francis seems to be the vicar of simple gospel truths simply stated. In good Franciscan tradition, he also bears witness to them more eloquently in deed than in speech.

The church has a rich intellectual tradition—artistic, philosophical, and theological. But the current pope largely renounces its use. This is not for the sake of launching some new tradition, as many progressive theologians did after the Second Vatican Council, but for the sake of a rhetorical poverty, a stripping down of the church’s witness to straightforward gospel truths: Blessed are the poor. Blessed are the meek. Blessed are those who hunger and thirst after righteousness.

Pope Francis seems to envision the church in a mendicant mode. We are to bear witness through our poverty of political power, social status, and cultural influence.

Bergoglio’s choice of Francis for a name doubtlessly reflects his reading of the signs of the times. Simply put, the age when Christianity reigned over Western culture and society has come to an end. We can gather in places like Wheaton College and the University of Notre Dame, creating our little Liechtensteins amid the great empire of the modern secular university. But for the most part, evangelicals and Catholics alike have neither place nor voice. Whether we like it or not, we are impoverished.

In this context, the message of Pope Francis speaks against the idea that we should form a rich, sophisticated counterculture. Instead, he seems to envision the church in a mendicant mode. We are to bear witness through our poverty of political power, social status, and cultural influence. Instead of St. Benedict, we are to imitate St. Francis.

Of course, not all of us are called to literal poverty, though perhaps more of us are called to it than we’d like to admit. Yet the simple truth simply stated remains. Whether our renunciations of the world are spiritual or literal, inward or outward, the Franciscan way of poverty is one of immediacy. We must surely renew and rebuild the intellectual life of our churches. But this project will take a long time. Meanwhile, we can conform ourselves to Christ right now. We can bear witness right now. There’s nothing about the poverty of our cultural dispossession and our intellectual marginality that prevents us from saying, “The Lord is risen.” In fact, we are better able to say it when we are poor.

A Simple ‘Yes’

We live in a paradoxical time of expansive possibilities, combined with a feeling that life is a long trudge toward a distant, elusive goal. Warm, well-fed, entertained, ministered to by modern medicine, yet we feel anxious and fearful. Our first impulses are toward self-protection, which we do through accumulation. And it’s striking how much we think we need. Getting a college degree has become a “necessity.” We scramble for credentials that aren’t so much stepping stones to a goal as so many layers of armor that will protect us from life’s perils.

The habit of irony in our time powerfully expresses our culture’s impulse to self-protect. Irony creates a safe distance, an insulating layer. It’s a way to be with others without revealing ourselves, a way to cover our existential nakedness. A dismissive “whatever” insulates us from the emotional dangers of disappointment, the possibility that what we truly desire can’t be had or embraced. Surrounded by unprecedented wealth, we fear deprivation. In an age of hypercommunication, we fear revealing ourselves to others.

In this context of fear—and I believe we are motivated by fear today much more than by ambition—the pope’s Franciscan qualities have a special resonance and importance. The way of Francis contradicts our assumption that we need to slave away to build up an invincible wall of self-protection. Fullness of life can be had in a moment, in a simple “yes” to Christ.

For this reason, Pope Francis brings us up short. His gestures of poverty and his blunt style help us to see that what we desire—the joy of genuine freedom and fullness of life—is right there for the taking. We don’t need a fully funded 401k. We don’t need an advanced theology degree. We don’t need to be smart or good-looking. We don’t even need to be good and virtuous. To Christ’s clear words—“Take up your cross and follow me”—we need only to say yes.

R. R. Reno is editor of First Things magazine and author of Fighting the Noonday Devil—and Other Essays Personal and Theological (Eerdmans).