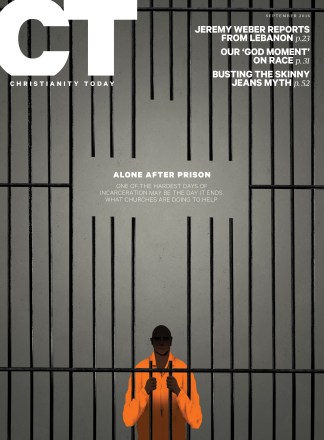

Two blocks from the North Carolina Capitol, a dozen women are sitting on couches in a circle. Unmarked, with dark windows and fluorescent lights overhead, the upstairs room of Raleigh’s First Presbyterian Church smells musty and damp. Alice Noell’s Job Start program is in session, and the women are here to make sense of their lives.

The women currently live in the Raleigh Correctional Center for Women, which they leave five days a week to attend Noell’s 15-week course. Noell—an energetic and passionate teacher—isn’t speaking right now. Instead, she’s invited one of her former students to address a captive audience.

All of the women, equal numbers black and white, lean in as Miea Walker walks in, waves, and finds the recliner in the center of the circle. Walker, 45, was released from prison in March 2012, a date still fresh enough for her to drop the names of wardens and guards.

“I know what it feels like,” she says. “You feel like you can’t breathe. You’re in a box all day long.”

During her own nine-year sentence for embezzlement, Walker received her bachelor’s degree and two associate’s degrees. Beyond the course load, the hardest work was moving past the depression she believes was brought on by strained family relationships and a missing relationship with God.

She scans the room, makes eye contact with each woman, takes a breath, and begins: “Broken people can’t serve broken people.”

Immediately, the women reach for their pens and begin transcribing her words in their notebooks.

An Atypical Story

Walker’s story has many elements in common with the stories of the 600,000 Americans who are imprisoned annually. She’s African American and, like many women who have served time, was affected by domestic violence, in her case as a child.

But her story is also unusual, and instructively so. Walker returned from prison to a spouse. She recently celebrated 16 years of marriage with her husband, Kevin. (“I tried to get my husband to leave me, but he wouldn’t.”) She had access to housing, professional connections, transportation, and a spiritual community. Few women (Walker calls them her “sisters”) or men leave prison with these relational and economic advantages.

Walker was also sentenced to a prison in the city where she already resided. Her husband was able to visit consistently during her sentence, and the relationships Walker formed in prison could be maintained after she went home.

“I can’t talk about my story without talking about the community,” said Walker. “I didn’t get here all by myself.”

“I can’t talk about my story without talking about the community,” said Walker. “I didn’t get here all by myself.”

Central to that community was the church. In addition to Noell’s Job Start program, two women from a local congregation volunteered to mentor her. Walker began attending church with one of them, a congregation she stayed in for two years after her release before finding another community. The church—in this case, two majority-black congregations—has played a critical role in Walker’s transition from prison. But in this, too, Walker’s story is all too unusual among the 600,000 people released from American correctional facilities every year.

This is not so much for a lack of prison ministries, in which evangelical Christians have specialized and sometimes excelled, as much as it is a missed opportunity for ministry after prison. “Why is it that the same vans that come to the prison on Wednesday and Sunday nights to take us to Bible study seem hesitant to pick us up from our homes now that we are released?” said Dennis Gaddy, founder and executive of Community Success Initiative, a Raleigh-based organization that serves the recently released. Gaddy himself was formerly incarcerated.

The United States has more than 300,000 churches, meant to welcome, build, and sustain relationships—and there aren’t many groups that need that kind of relational support more than people who are released from jail. For every Miea Walker who emerges to an intact marriage, committed mentors, and a welcoming church community, far more former prisoners find themselves adrift, suffering the last and in some ways cruelest stage of the uniquely American drama of incarceration.

Jillian Clark

Jillian ClarkMassive Incarceration

The incarceration rate in the United States has surged over the past two generations. In 1985, 743,000 people were incarcerated in the United States, reports the Department of Justice. If that number had simply kept pace with the population, it would be 988,000 today. Instead, it’s 2.3 million, including prisons, jails, juvenile correctional facilities, military prisons, immigration detention facilities, and civil commitment centers. China and India—with more than 1 billion citizens each—together incarcerate roughly the same number of individuals as the United States alone, with its population of just 315 million. The great majority of those imprisoned are still men, but the number of women imprisoned grew 700 percent from 1980 to 2014. Today they represent 9 percent of the state and federal prison population.

With the growing rates of incarceration has come increasing criticism of a system that many believe goes well beyond jails and prisons—a perspective summarized in the phrase “mass incarceration.” This term, Ohio State law professor Michelle Alexander wrote in her 2010 New York Times bestseller, The New Jim Crow, “refers not only to the criminal justice system but also to the larger web of laws, rules, policies, and customs that control those labeled criminals both in and out of prison. Once released, former prisoners enter a hidden underworld of legalized discrimination and permanent social exclusion. They are members of America’s new undercaste.”

Alexander’s book was the first in a number of best-selling challenges to the criminal justice system, including Bryan Stevenson’s Just Mercy and Ta-Nehisi Coates’s Between the World and Me. At the same time, a series of cases of police misconduct (many caught on camera and shared widely on social media), some undisputed and some hotly debated, have given rise to the movement best known by a Twitter hashtag, #BlackLivesMatter. Like Alexander, Black Lives Matter activists generally maintain that incarceration is one part of a larger, comprehensively dysfunctional system characterized by, among other issues, egregiously violent police interactions (often between white officers and black citizens), a disproportionate number of black and poor (or both) people facing the death penalty, and high numbers of black and brown people in prison.

Not all who have studied mass incarceration agree with Alexander’s assertion that it effectively represents a “new Jim Crow.” James Forman Jr., a professor at Yale Law School, highlights the “rising levels of violent crime [in the 1960s] and demands by black activists for harsher sentences” in his 2012 response to Alexander. (The latter observation was recently expounded upon in Michael Javen Fortner’s Black Silent Majority.) Violent crime, more so than the “War on Drugs,” is responsible for the ballooning of the prison population, Forman argues. And “while rates of drug offenses are roughly the same throughout the population, blacks are overrepresented among the population for violent offenses.”

What no one disputes is that the US criminal justice system is extraordinarily expensive. Corrections is the third-largest category of state spending, behind education and health care. As state corrections budgets ballooned in the early 2000s, reform became an increasingly bipartisan cause. Several states that lead in incarceration rates, including Alabama, Mississippi, and Texas, have passed laws changing mandatory minimum requirements and have found alternative punishments for nonviolent offenders.

Last year, Republican senator Chuck Grassley and Democratic senator Dick Durbin introduced the Sentencing Reform and Corrections Act of 2015. The bill gives judges more discretion in sentencing (rolling back mandatory minimum laws that became popular in the 1980s and 1990s), expands prison rehabilitation programs, and extends changes made in 2010 to mitigate the disparity in sentencing for possession of the same amounts of powder and crack cocaine.

The support for prison reform is strikingly bipartisan.

The bill has yet to clear the Senate. (While many Republicans support the bill, several party members’ opposition has made Majority Leader Mitch McConnell reluctant to bring the legislation to the floor.) Meanwhile, Speaker of the House Paul Ryan has said he wants to address criminal justice reform through several smaller initiatives. Nearly a dozen small bills have passed through the House Judiciary Committee, and with more on the way, combined legislation will likely be brought to a vote later this year.

The support for prison reform is strikingly bipartisan. The Senate bill has supporters as diverse as the conservative Koch brothers, the American Civil Liberties Union, and the Human Rights Campaign. And it is also backed by Prison Fellowship, the best-funded and most widely recognized evangelical organization in the field.

Evangelicals in Prison

Founded in 1976 by the formerly incarcerated Nixon aide Chuck Colson, Prison Fellowship exemplifies the strengths and weaknesses of Christian engagement with the criminal justice system. The ministry primarily focuses on currently incarcerated people and their families. A small advocacy team briefs legislators and builds coalitions with like-minded groups (see sidebar on page 46).

Over the past five years, Prison Fellowship has averaged $40 million in revenue, almost certainly the largest sum raised by any non-governmental organization, Christian or secular, for prison-related work. Though Colson’s death in 2012 deprived the ministry of its most visible spokesman and fundraiser, Prison Fellowship’s total contributions increased by 7.7 percent in 2015. “There’s no single factor contributing to the uptick,” said senior vice president for marketing and communications Sara Marlin.

True to the experience of its founder, who came to faith in prison, Prison Fellowship measures its impact in terms of evangelism and discipleship. Last year, it hosted more than 200 evangelism events attended by more than 23,000 prisoners. About 4,800 prisoners made decisions for or recommitments to Christ.

Since 2007, cash donations to the roughly 85 prison-related ministries accredited by the ECFA have dropped almost every year.

But Prison Fellowship is largely alone in its efforts. In spite of the dramatic growth of incarceration, ministries to those in and returning from prison remain a distinct minority of evangelical organizations. Since 2007, cash donations to the roughly 85 prison-related ministries accredited by the Evangelical Council for Financial Accountability (ECFA) have dropped almost every year. In 2014, the most recent year in ECFA records, prison ministries received $55.7 million. In comparison, relief and development agencies received $2.5 billion in 2014, and child sponsorship organizations received close to $739 million.

Prison programs, as well as ECFA’s two other categories that intersect with incarceration—alcohol and drug rehabilitation ($44.7 million) and community development ($39.6 million)—are among the lowest-funded categories of evangelical activity, according to ECFA metrics.

Disparate Impact

One reason for this disparity in giving may be the de facto segregation of American life, including churches. Millions of white Christians reside in communities where the extent of incarceration is all but invisible. The difference between white and black perspectives on incarceration is stark: 33 percent of white evangelicals said that the rapid growth of inmates is “unjust,” compared to 71 percent of African American evangelicals, according to a recent LifeWay poll (see sidebar on page 43). The split is even wider on whether the racial disparity in the inmate population is unjust: 38 percent of white evangelicals say it is, compared to 84 percent of African American evangelicals.

“No one can deny the disparate impact on minorities, but what people tend to disagree on is why these disparities happen and how we fix them,” said Heather Rice-Minus, a senior policy adviser at Prison Fellowship.

“I’m just not sure that the strategy of having people own and name that the system is racist is going to lead to effective outcomes for the people we are trying to serve,” said Rice-Minus.

Indeed, conservative efforts for criminal justice reform at the state level have been driven more by the fiscal burden of the system and high recidivism rates than by a perceived racial injustice. “We know that we’re incarcerated well beyond the return on investment at this point,” Rice-Minus said. “But you’re basically asking [legislators] to say, ‘I did that for racial motivations.’ I think many of them, truly, thought they were protecting the African American community.”

Not everyone agrees.

“It’s disingenuous to talk about prison reform while ignoring the realities of the disproportionate rate of incarceration,” said Shawn Casselberry, who wrote his seminary doctoral thesis on evangelical engagement in criminal justice reform. “When it’s obvious that outcomes at every point of the justice process are impacted by racial and social location, then it is irresponsible not to address it.

“When an African American who doesn’t have a criminal record is less likely to get hired than a white person with a record, we have to name these areas. When African Americans get 20 percent longer sentences than whites for the same crime, we have to name it.”

“You might change the stats around how long people are incarcerated, but you won’t change the incarceration pattern without taking into account race and class,” said Dominique Gilliard, who pastors New Hope Covenant Church in Oakland, California. He points to what activists call the “school to prison pipeline.” It begins when children—a disproportionate number of them black and Latino—begin getting suspended in elementary school. Such school punishments often escalate into arrests. “The ‘New Jim Crow’ lens helps us see the comprehensive reality of who is behind bars and how long they are behind bars, starting with elementary schools,” Gilliard said.

He argues that avoiding the question of race will only perpetuate a “consistent stalemate of distrust” between a community and the criminal justice system.

“I’m becoming more and more convinced that the problem is not just with law enforcement,” said Gilliard. “We limit the conversation when we stop it there. It’s not just law enforcement who have these racialized projections. . . . It also affects judges, district attorneys, and those involved with sentencing.”

Evangelicals tend to be disengaged from these broader structural issues, said Casselberry, who is white. Generally speaking, conservatives believe the most important change occurs at the individual rather than the systemic level.

“Conservative groups tend to emphasize personalized ministry forms such as one-on-one visitation, Angel Tree Christmas gifts, and conducting evangelistic worship services,” Casselberry said.

Prison Fellowship reported fewer than 3,000 messages sent to Congress in support of criminal justice reform efforts last year.

Volunteer numbers tell the same story: about 11,000 volunteers worked with Prison Fellowship inside correctional facilities last year, each one making a major commitment of time. But Prison Fellowship reported fewer than 3,000 messages sent to Congress in support of criminal justice reform efforts.

Casselberry would like to see evangelicals of all political affinities broaden their efforts. “Christians really need to be working in prisons, doing advocacy, and helping with reentry,” said Casselberry, who also directs Mission Year, a program in which young people live and serve in an under-resourced neighborhood for a year. “We’ve divided these areas based on political affiliation, but we really need to be involved in all three levels.”

A Promise to God

From the beginning, Miea Walker’s relationship with the church was strained. Her parents separated when she was two. Most of her childhood was spent with her mother, her grandmother, and her grandmother’s boyfriend.

While the boyfriend never attacked Walker, he verbally abused her mother and physically abused and berated her grandmother.

“Church was a pretense. It was very organizational, very bureaucratic,” Walker said. “It didn’t have the heart of what it means to serve God and serve his children. Even though people in the community knew [about the abuse], they maintained the secret and the lie.

“I just remember saying that when I got older, I would never go to church again in my life. We were told to hide our pain. We had to put our good faces on.”

The abuse took a toll. “I’m pretty sure depression entered my life when I was a kid, having witnessed abuse at least twice a week,” said Walker. “I hated my grandmother for allowing this to happen. I hated my mom because there weren’t any other choices that she had. I carried all of that into adulthood.”

After high school, she enrolled at University of North Carolina–Chapel Hill, a decision she now refers to as “one of the worst I could have made at the time.”

“It’s nothing against the school,” said Walker, a diehard Tar Heels fan. “But I was a young person suffering from chronic brokenness, shame, and despair.”

Over the next few years, Walker struggled with insecurities that made it difficult for her to build close or healthy relationships. “Lying became like second nature to me,” she said. Walker dropped out of school and was convicted of several financial crimes. After finding a job as a paralegal, Walker was arrested again, this time for embezzling money at her office. She was convicted in 2003.

“My boss at the time, she really loved me,” said Walker. “I broke her and I broke her heart.”

As Walker realized that her crime carried a hefty sentence, her depression worsened. She attempted suicide three times.

“There were attempts to have a relationship with Christ, but I could never trust who God was. My relationship with him was very superficial,” she said.

While she waited for her sentence, after a year and a half of intense, relentless migraines, Walker began praying, I’m so tired. I don’t know what else to do, and you won’t allow me to die. I’m done fighting.

Several days after her prayer, Walker’s migraines suddenly ended. And she made a promise to God: She’d get off her depression medication and start going to therapy consistently, be honest with her psychiatrist, and complete her education. God would take care of the rest.

Over the next nine years, Walker did all three.

“You’ve probably heard people say that prison saved their life,” said Walker. “This was the opportunity for God to remove everything else I had going in my life and for him to be the first, middle, and last of what I had going on all day, every day.”

The Long Way Home

Every year, more than half a million Americans leave prison. Little gets easier when they are released. In addition to trying to reestablish often strained relationships with family and friends, many struggle to secure housing and jobs. Some drug crimes also make a convicted person ineligible for public housing. In some states, those with felony convictions cannot apply for food stamps.

In North Carolina, people on parole can’t vote, apply for Medicare or Medicaid, or live in public housing, said Walker. “I know of two women who committed suicide when they came home. Some have died due to poor health care. And others are just trying to hang on.”

The process can seem so overwhelming, several advocates told CT, that some commit crimes so they can return to prison.

The process can seem so overwhelming, several advocates told CT, that some commit crimes so they can return to prison.

Yet engaging churches to step in at the point of re-entry is challenging. At a recent meeting of the Capitol Area Reentry Council, North Carolina state and nonprofit employees discussed how to galvanize churchgoers to build relationships and help those coming home. While more than 600 volunteers served inside correctional facilities, “only a handful” served the reentry process, according to council documents. One reason: working inside the prison allows volunteers to interact “safely” with the criminal justice system.

Attendees floated multiple reasons why churches weren’t on board, including misguided fear and inadequate teaching on forgiveness. For those on the inside, it’s hard not to be cynical about those who help only in prisons, without also serving those coming home.

“Here’s the thinking of the people who are in prison toward these volunteers,” said Gaddy. “They call the church fake.”

“There has to be a sacrifice within the Christian community. We have to look at our selfishness and our actions and show that we are more than about status,” said Sandi Velez, who runs Puentes, a bilingual prison ministry in Raleigh.

Finding volunteers is not the only problem. Not everyone is cut out to work with the previously incarcerated. Walker remembers one mentor who broke off her relationship with a previously incarcerated woman who had returned to her addiction.

It may be no surprise that Noell, one of Walker’s closest mentors, struggled herself. Noell was arrested and briefly incarcerated when she was in her 20s.

“The church is the answer,” she said. “But it is not equipped.”

One group seeking to resource the church is the Christian Community Development Association (CCDA) which, in recent years, has created a series of events and curriculum for leaders seeking to educate their congregations. Last year, it hosted four film events in churches around the country designed to educate about the criminal justice system while providing time for debrief and reflection. This February marked the CCDA’s third annual Locked in Solidarity event, a prayer and advocacy day designed to allow those directly impacted by mass incarceration to share their stories.

Urban Entry, a video series designed to spark conversation among Christians around topics like poverty and race relations, will feature Walker for its latest film about mass incarceration.

“I’m hoping that the way that [Walker] shares her story changes the way people perceive people that were incarcerated,” said director Scott Lundeen.

“The church is the answer,” she said. “But it is not equipped.”

Earlier this year, Prison Fellowship launched its Second Prison Project (SPP), named for the myriad legal and social obstacles confronting the majority of those returning home. The group has organized Second Chance 5K events to foster connections between those with criminal records and those outside this community.

“We want to raise awareness of the 65 million Americans trapped in the ‘second prison’ of collateral consequences from criminal conviction,” said Rice-Minus. “One of the key goals of the project in the coming year is to engage business owners (particularly Christians) in providing employment opportunities to those with criminal history.”

The SPP is also building a series of local chapters designed to amplify the voices of those with a criminal record, said director Jesse Wiese.

“Chapters will be dedicated to the values of service, advocacy, and leadership and will constantly challenge the cultural status quo perception of people with a criminal record,” said Wiese.

Jobs After Jail

Shortly after returning home, Walker got a job at Jobs for Life (JFL). For more than two decades, the organization has provided support and training to churches and nonprofits offering job skills training to unemployed people. The classes are open to anyone, regardless of background, but about a third of attendees were previously incarcerated. Eight of ten students graduate (they must miss three or fewer classes to do so), and 60 percent of those find employment.

JFL’s model depends strongly on relationships between students and their mentors, who are asked to leverage their professional network, and the church’s at large, to help the student find employment. It judges its success on the number of participating churches and organizations, how equipped they are, how equipped JFL students are, and the post-class outcomes for JFL students, says CEO David Spickard.

“We could sum up everything we do as relationships,” said Spickard. “It’s not about jobs. We’re simply trying to put the church in a place where it’s building meaningful relationships with people in need, and then issues [like housing] begin to get taken care of because of mending those broken relationships. If we just think about transactions, like giving people things, we haven’t solved the relationship problem, which really is at the root of all of this.”

Like many evangelical groups that serve previously incarcerated people, JFL does not directly advocate for broader systemic change. Instead, JFL sees personal transformation as key.

“We would be more inclined to get to the root issue,” said Spickard. “You can ‘ban the box,’ ”—a legislative proposal that would forbid employers from asking about prior convictions on job applications—“but you may not have solved the problem yet.”

A more effective strategy, Spickard believes, is training someone who was formerly incarcerated to bring up their record head-on when meeting with a potential employer.

“We teach them that whoever gets to that question first wins,” he said.

Dominique Gilliard’s 140-person church has tried another approach. New Hope Covenant rents space from the Young Employment Partnership (YEP), a secular organization that helps young people with criminal records obtain their GED and land jobs.

In addition to serving as volunteers in YEP’s GED and education programming, church attendees offer pastoral care for emotionally hurting youth and their families.

“If people can be conversant in these realities and engage that pain, they will come to explore God through your presence in their life,” said Gilliard.

“We’re explicit about who we are,” said Gilliard about his church’s involvement. “We’re not there to be directly proselytizing to people, but we never have to hide the lamp under a bushel.”

Christian Stronghold, a church in Philadelphia, began ministering to prisoners because of the number of church attendees with loved ones in the system, said district pastor Larry James. The church soon realized that in order to fight recidivism rates, it would need to continue the relationships it built in the correctional facilities once these individuals returned home.

Two years ago, Christian Stronghold launched the West Philadelphia Coalition, a network of 15 churches in the area, to help returnees find jobs, housing, and education. (In fact, the churches begin preparing for an inmate’s upcoming reentry prior to his or her release.) Each previously incarcerated person also gets a mentor. The network has a close relationship with companies like Lowes, Home Depot, and Comcast, and often writes a letter to these potential employers on behalf of the person returning home, vouching for him or her.

All but two of the churches are predominantly African American, but “I don’t know anyone among the congregations that doesn’t know someone who is incarcerated,” said James.

Thriving Without Forgetting

With her growing role as an instructor and advocate, Miea Walker is unusual in one more respect: Although millions of Americans have been incarcerated, few have had opportunities to speak about their experiences and shape the prison system to which they belonged.

That’s changing, says Gaddy, well known in the Raleigh area for his advocacy for formerly incarcerated people.

“After all, if you think about it, the people who have led on the front lines of every major movement were those who were impacted,” he said, pointing to the civil rights movement.

Since coming home, Walker has spoken at conferences, joined committees, and enrolled in courses to study addiction. (Gaddy calls her criminal justice reform’s “biggest rising star.”)

But Walker hasn’t forgotten about prison. And she’s determined the church won’t either.

“I wake up and my prayer is always, ‘God, break my heart and help me to be a better sister to my brothers and sisters. Help to me find a way to bridge that gap, to help them know that they are created in your image, and that you love them dearly.’ ”

Morgan Lee is assistant editor of CT.