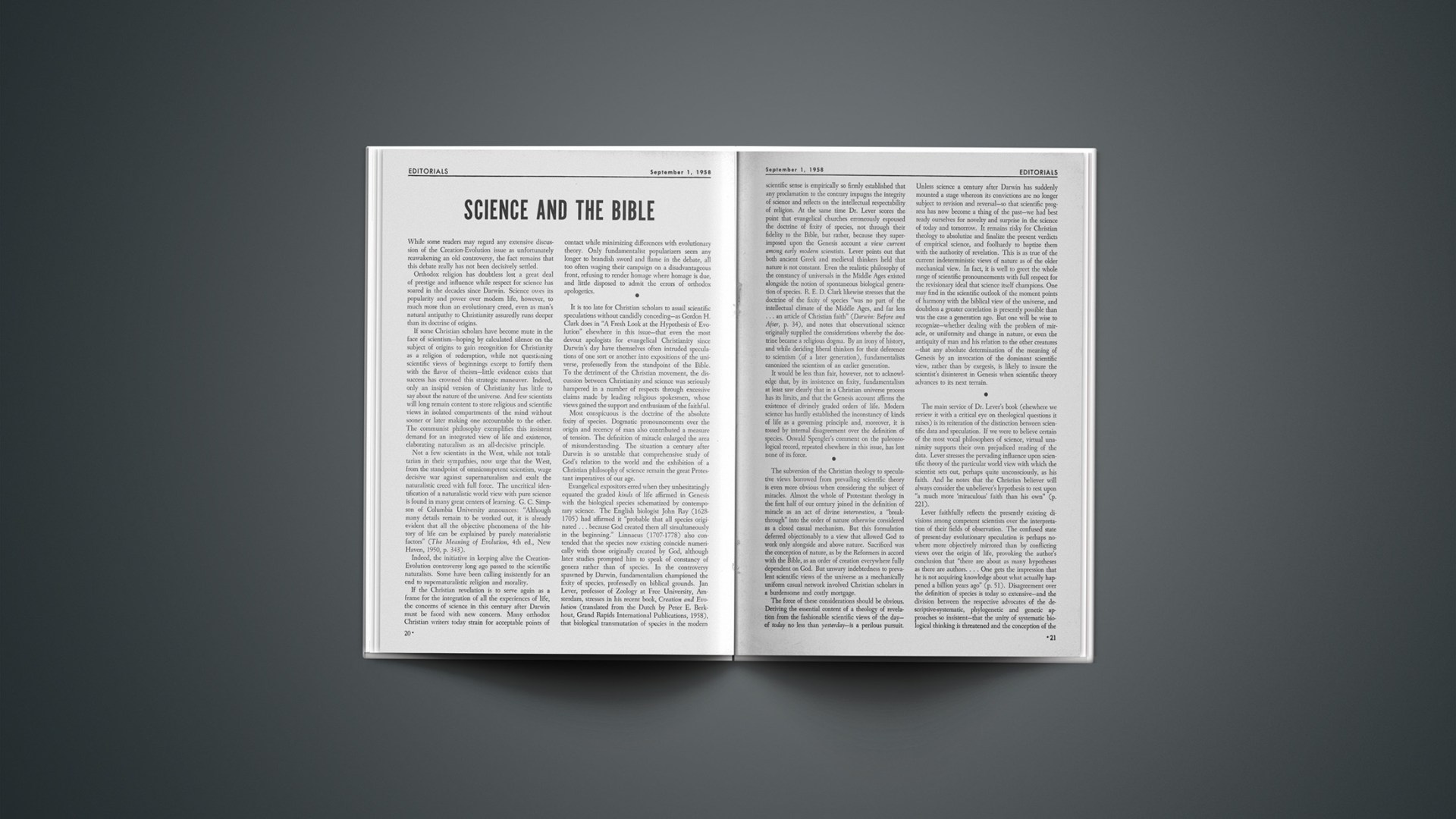

While some readers may regard any extensive discussion of the Creation-Evolution issue as unfortunately reawakening an old controversy, the fact remains that this debate really has not been decisively settled.

Orthodox religion has doubtless lost a great deal of prestige and influence while respect for science has soared in the decades since Darwin. Science owes its popularity and power over modern life, however, to much more than an evolutionary creed, even as man’s natural antipathy to Christianity assuredly runs deeper than its doctrine of origins.

If some Christian scholars have become mute in the face of scientism—hoping by calculated silence on the subject of origins to gain recognition for Christianity as a religion of redemption, while not questioning scientific views of beginnings except to fortify them with the flavor of theism—little evidence exists that success has crowned this strategic maneuver. Indeed, only an insipid version of Christianity has little to say about the nature of the universe. And few scientists will long remain content to store religious and scientific views in isolated compartments of the mind without sooner or later making one accountable to the other. The communist philosophy exemplifies this insistent demand for an integrated view of life and existence, elaborating naturalism as an all-decisive principle.

Not a few scientists in the West, while not totalitarian in their sympathies, now urge that the West, from the standpoint of omnicompetent scientism, wage decisive war against supernaturalism and exalt the naturalistic creed with full force. The uncritical identification of a naturalistic world view with pure science is found in many great centers of learning. G. C. Simpson of Columbia University announces: “Although many details remain to be worked out, it is already evident that all the objective phenomena of the history of life can be explained by purely materialistic factors” (The Meaning of Evolution, 4th ed., New Haven, 1950, p. 343).

Indeed, the initiative in keeping alive the Creation-Evolution controversy long ago passed to the scientific naturalists. Some have been calling insistently for an end to supernaturalistic religion and morality.

If the Christian revelation is to serve again as a frame for the integration of all the experiences of life, the concerns of science in this century after Darwin must be faced with new concern. Many orthodox Christian writers today strain for acceptable points of contact while minimizing differences with evolutionary theory. Only fundamentalist popularizers seem any longer to brandish sword and flame in the debate, all too often waging their campaign on a disadvantageous front, refusing to render homage where homage is due, and little disposed to admit the errors of orthodox apologetics.

It is too late for Christian scholars to assail scientific speculations without candidly conceding—as Gordon H. Clark does in “A Fresh Look at the Hypothesis of Evolution” elsewhere in this issue—that even the most devout apologists for evangelical Christianity since Darwin’s day have themselves often intruded speculations of one sort or another into expositions of the universe, professedly from the standpoint of the Bible. To the detriment of the Christian movement, the discussion between Christianity and science was seriously hampered in a number of respects through excessive claims made by leading religious spokesmen, whose views gained the support and enthusiasm of the faithful.

Most conspicuous is the doctrine of the absolute fixity of species. Dogmatic pronouncements over the origin and recency of man also contributed a measure of tension. The definition of miracle enlarged the area of misunderstanding. The situation a century after Darwin is so unstable that comprehensive study of God’s relation to the world and the exhibition of a Christian philosophy of science remain the great Protestant imperatives of our age.

Evangelical expositors erred when they unhesitatingly equated the graded kinds of life affirmed in Genesis with the biological species schematized by contemporary science. The English biologist John Ray (1628–1705) had affirmed it “probable that all species originated … because God created them all simultaneously in the beginning.” Linnaeus (1707–1778) also contended that the species now existing coincide numerically with those originally created by God, although later studies prompted him to speak of constancy of genera rather than of species. In the controversy spawned by Darwin, fundamentalism championed the fixity of species, professedly on biblical grounds. Jan Lever, professor of Zoology at Free University, Amsterdam, stresses in his recent book, Creation and Evolution (translated from the Dutch by Peter E. Berkhout, Grand Rapids International Publications, 1958), that biological transmutation of species in the modern scientific sense is empirically so firmly established that any proclamation to the contrary impugns the integrity of science and reflects on the intellectual respectability of religion. At the same time Dr. Lever scores the point that evangelical churches erroneously espoused the doctrine of fixity of species, not through their fidelity to the Bible, but rather, because they superimposed upon the Genesis account a view current among early modern scientists. Lever points out that both ancient Greek and medieval thinkers held that nature is not constant. Even the realistic philosophy of the constancy of universals in the Middle Ages existed alongside the notion of spontaneous biological generation of species. R. E. D. Clark likewise stresses that the doctrine of the fixity of species “was no part of the intellectual climate of the Middle Ages, and far less … an article of Christian faith” (Darwin: Before and After, p. 34), and notes that observational science originally supplied the considerations whereby the doctrine became a religious dogma. By an irony of history, and while deriding liberal thinkers for their deference to scientism (of a later generation), fundamentalists canonized the scientism of an earlier generation.

It would be less than fair, however, not to acknowledge that, by its insistence on fixity, fundamentalism at least saw clearly that in a Christian universe process has its limits, and that the Genesis account affirms the existence of divinely graded orders of life. Modern science has hardly established the inconstancy of kinds of life as a governing principle and, moreover, it is tossed by internal disagreement over the definition of species. Oswald Spengler’s comment on the paleontological record, repeated elsewhere in this issue, has lost none of its force.

The subversion of the Christian theology to speculative views borrowed from prevailing scientific theory is even more obvious when considering the subject of miracles. Almost the whole of Protestant theology in the first half of our century joined in the definition of miracle as an act of divine intervention, a “breakthrough” into the order of nature otherwise considered as a closed casual mechanism. But this formulation deferred objectionably to a view that allowed God to work only alongside and above nature. Sacrificed was the conception of nature, as by the Reformers in accord with the Bible, as an order of creation everywhere fully dependent on God. But unwary indebtedness to prevalent scientific views of the universe as a mechanically uniform casual network involved Christian scholars in a burdensome and costly mortgage.

The force of these considerations should be obvious. Deriving the essential content of a theology of revelation from the fashionable scientific views of the day—of today no less than yesterday—is a perilous pursuit. Unless science a century after Darwin has suddenly mounted a stage whereon its convictions are no longer subject to revision and reversal—so that scientific progress has now become a thing of the past—we had best ready ourselves for novelty and surprise in the science of today and tomorrow. It remains risky for Christian theology to absolutize and finalize the present verdicts of empirical science, and foolhardy to baptize them with the authority of revelation. This is as true of the current indeterministic views of nature as of the older mechanical view. In fact, it is well to greet the whole range of scientific pronouncements with full respect for the revisionary ideal that science itself champions. One may find in the scientific outlook of the moment points of harmony with the biblical view of the universe, and doubtless a greater correlation is presently possible than was the case a generation ago. But one will be wise to recognize—whether dealing with the problem of miracle, or uniformity and change in nature, or even the antiquity of man and his relation to the other creatures—that any absolute determination of the meaning of Genesis by an invocation of the dominant scientific view, rather than by exegesis, is likely to insure the scientist’s disinterest in Genesis when scientific theory advances to its next terrain.

The main service of Dr. Lever’s book (elsewhere we review it with a critical eye on theological questions it raises) is its reiteration of the distinction between scientific data and speculation. If we were to believe certain of the most vocal philosophers of science, virtual unanimity supports their own prejudiced reading of the data. Lever stresses the pervading influence upon scientific theory of the particular world view with which the scientist sets out, perhaps quite unconsciously, as his faith. And he notes that the Christian believer will always consider the unbeliever’s hypothesis to rest upon “a much more ‘miraculous’ faith than his own” (p. 221).

Lever faithfully reflects the presently existing divisions among competent scientists over the interpretation of their fields of observation. The confused state of present-day evolutionary speculation is perhaps nowhere more objectively mirrored than by conflicting views over the origin of life, provoking the author’s conclusion that “there are about as many hypotheses as there are authors.… One gets the impression that he is not acquiring knowledge about what actually happened a billion years ago” (p. 51). Disagreement over the definition of species is today so extensive—and the division between the respective advocates of the descriptive-systematic, phylogenetic and genetic approaches so insistent—that the unity of systematic biological thinking is threatened and the conception of the essence of living organic structures unsure (pp. 125 f.). The question of the antiquity of man is also shadowed by conflict. The debate turns on whether the relation between present-day man and animate forerunners is to be explored simply on an anatomical basis, or also on a functional and cultural basis (pp. 158 ff.). Lever’s personal opinion is that, despite the cardinal gaps still existing in scientific knowledge, the Christian need not have any objection to “the general hypothesis of a genetic continuity of all living organisms, man not excluded” (p. 203), and he thinks man already existed upon the earth in the Pleistocene epoch 500,000 years ago. But he asserts also that “the opinion expressed at times, that it has been proved that man descended from anthropoids, lacks a scientific basis” (p. 157), and that not enough attention has been paid to the respects in which they differ (pp. 182 f.).

Lever summarizes the data adduced by science in the century since Darwin as follows:

It can be considered as definite that initially there were no living beings present on the earth, and that today no really new life originates.… Life must have made its appearance … at a definite moment or … period of time in the history of the earth. Records about this are entirely unknown to us.… Equally unknown to us is the first appearance of the phyla to be differentiated in the flora and fauna, as well as the mutual relation of these phyla. As far as the origin of the classes and other higher categories are concerned we are still largely in the dark, although here, in some instances, the indications are not entirely absent. Finally, the origin of man appears to be a much more complicated problem than was anticipated initially. The relation of the fossil hominid forms is strongly disputed. The criteria to determine what is a human being do not appear to lie in the sphere of the fossils. The only thing about which we are sure is that the species are not fixed, and that in the past they have changed to an important extent. Some mechanisms that play a part in these changes are known to us … (pp. 201 f.).

We are tempted only to comment that if Genesis tells us little about origins, modern science appears to tell us even less.

That is not to deny the magnificent contribution of science to our knowledge of the intricate behavior of the universe. Whoever closes his eyes to that contribution does so, of course, by the denial of his own modernity. But the fact remains that the great truths of the biblical creation narrative retain their validity for our scientific era, and that the twentieth century is in dire moral and spiritual straits for having neglected them. If we may borrow words from the chapter on “Science and Religion” in the volume Contemporary Evangelical Thought (Channel Press, 1957), some of the relevant truths of the Genesis account are: “that a sovereign, personal, ethical God is the voluntary creator of the space-time universe; that God created ex nihilo by divine fiat; that the stages of creation reflect an orderly rational sequence; that there are divinely graded levels of life; that man is distinguished from the animals by a superior origin and dignity; that the human race is a unity in Adam; that man was divinely assigned the vocation of conforming the created world to the service of the will of God; that the whole creation is a providential and teleological order.…” The larger New Testament disclosure reveals “that the word of creation is no mere instrumental word, but rather a personal Word, the Logos, who is the divine agent in creation; that this Logos permanently assumed human nature in Jesus Christ; that the God of creation and of revelation and of redemption and of sanctification and of judgment is one and the same God.…” If ever our discordant culture is to recover a unified outlook on all life’s experiences, it will be in the framework of this ideology.

College Classrooms And The Great Issues

Throngs of students are readying baggage for another year of collegiate and university study. Many will be pressed—in classroom and chapel—to recognize that human destinies may be swiftly changed by some significant scientific breakthrough in our age of invention. How many, we wonder, will be driven to decision over the deeper ideological issue, the struggle of Christianity against the secular tide which threatens to inundate both East and West?

In a recent chapel address on “Reason and Evangelical Faith,” Dr. Tunis Romein, professor of philosophy at Erskine College, recalled that “higher education sponsored by one evangelical denomination or another has often been criticized for its easygoing scholarship.” He contrasts this with the Greek rational tradition of excellence in scholarship, and its emphasis that learning can be pleasure only when it is preceded by some amount of pain. And he stresses that evangelically sponsored academic effort, which ought to surpass worldly standards of intellectual excellence, will be ignored if it does not meet those high standards.

Erskine Review quotes Professor Romein’s pointed words:

Now if the world rejects our academic activity because it is angry or disturbed, we can possibly consider such a reaction an indirect acknowledgment of an acceptable standard. But if the world simply ignores evangelical scholarship because of its lack of bite and challenge, we have reason to be disturbed about our Christian testimony in the field of learning.

This observation applicable to the specific relationship of evangelical faith to the academic world may have a meaningful application to the wider relationship of evangelical faith to the world at large. The disturbing question is not whether the world rejects the evangelical message, but whether the world ignores it, because if this be so we are failing the evangelical tradition at the point where it ought to be strongest, namely in its power to challenge the world.