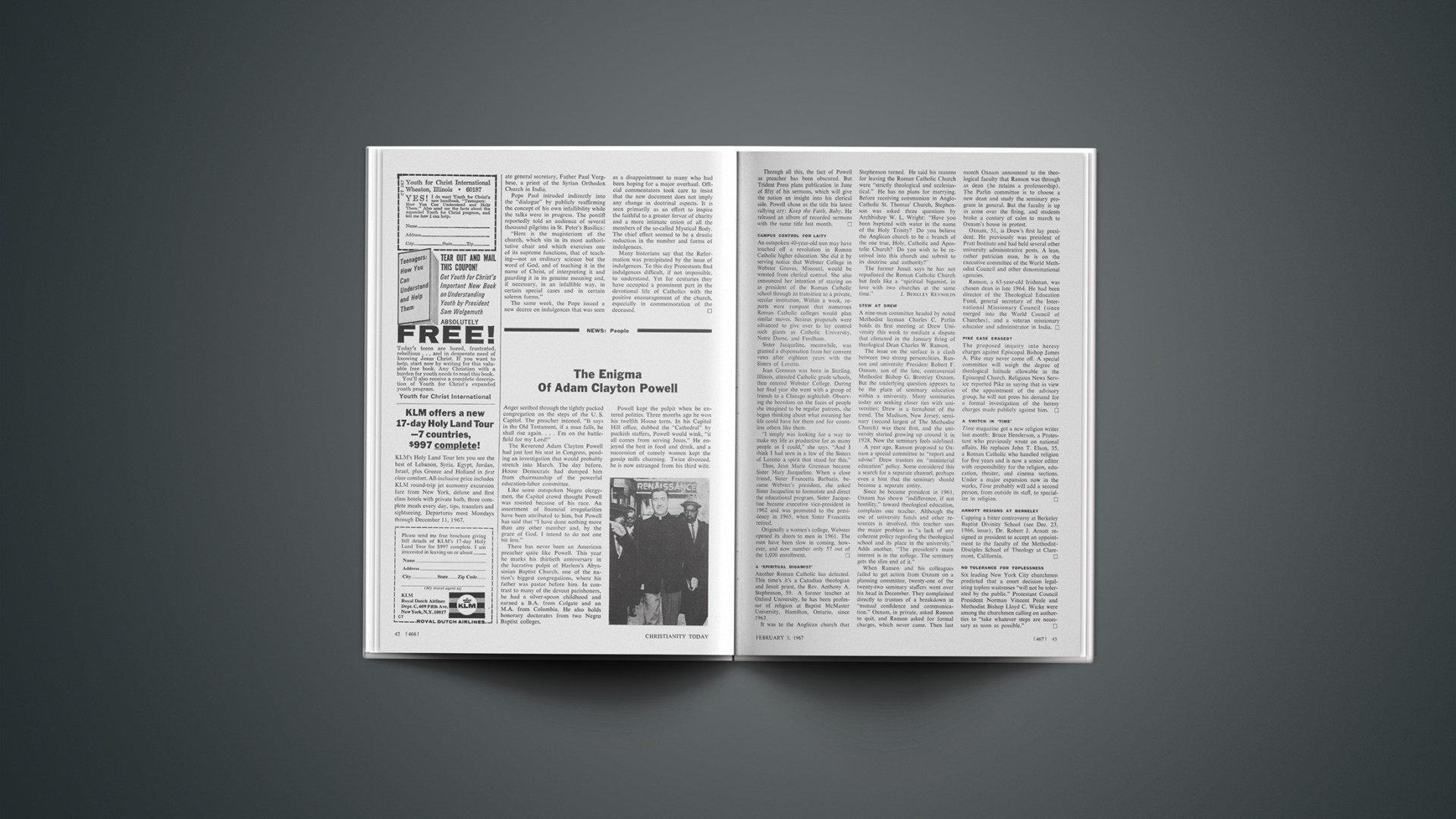

Anger seethed through the tightly packed congregation on the steps of the U. S. Capitol. The preacher intoned, “It says in the Old Testament, if a man falls, he shall rise again.… I’m on the battlefield for my Lord!”

The Reverend Adam Clayton Powell had just lost his seat in Congress, pending an investigation that would probably stretch into March. The day before, House Democrats had dumped him from chairmanship of the powerful education-labor committee.

Like some outspoken Negro clergymen, the Capitol crowd thought Powell was roasted because of his race. An assortment of financial irregularities have been attributed to him, but Powell has said that “I have done nothing more than any other member and, by the grace of God, I intend to do not one bit less.”

There has never been an American preacher quite like Powell. This year he marks his thirtieth anniversary in the lucrative pulpit of Harlem’s Abyssinian Baptist Church, one of the nation’s biggest congregations, where his father was pastor before him. In contrast to many of the devout parishoners, he had a silver-spoon childhood and earned a B.A. from Colgate and an M.A. from Columbia. He also holds honorary doctorates from two Negro Baptist colleges.

Powell kept the pulpit when he entered politics. Three months ago he won his twelfth House term. In his Capitol Hill office, dubbed the “Cathedral” by puckish staffers, Powell would wink, “it all comes from serving Jesus.” He enjoyed the best in food and drink, and a succession of comely women kept the gossip mills churning. Twice divorced, he is now estranged from his third wife.

Through all this, the fact of Powell as preacher has been obscured. But Trident Press plans publication in June of fifty of his sermons, which will give the nation an insight into his clerical side. Powell chose as the title his latest rallying cry: Keep the Faith, Baby. He released an album of recorded sermons with the same title last month.

Campus Control For Laity

An outspoken 40-year-old nun may have touched off a revolution in Roman Catholic higher education. She did it by serving notice that Webster College in Webster Groves, Missouri, would be wrested from clerical control. She also announced her intention of staying on as president of the Roman Catholic school through its transition to a private, secular institution. Within a week, reports were rampant that numerous Roman Catholic colleges would plan similar moves. Serious proposals were advanced to give over to lay control such giants as Catholic University, Notre Dame, and Fordham.

Sister Jacqueline, meanwhile, was granted a dispensation from her convent vows after eighteen years with the Sisters of Loretto.

Jean Grennan was born in Sterling, Illinois, attended Catholic grade schools, then entered Webster College. During her final year she went with a group of friends to a Chicago nightclub. Observing the boredom on the faces of people she imagined to be regular patrons, she began thinking about what meaning her life could have for them and for countless others like them.

“I simply was looking for a way to make my life as productive for as many people as I could,” she says. “And I think I had seen in a few of the Sisters of Loretto a spirit that stood for this.”

Thus, Jean Marie Grennan became Sister Mary Jacqueline. When a close friend, Sister Francetta Barbaris, became Webster’s president, she asked Sister Jacqueline to formulate and direct the educational program. Sister Jacqueline became executive vice-president in 1962 and was promoted to the presidency in 1965, when Sister Francetta retired.

Originally a women’s college, Webster opened its doors to men in 1961. The men have been slow in coming, however, and now number only 57 out of the 1,000 enrollment.

A ‘Spiritual Bigamist’

Another Roman Catholic has defected. This time’s it’s a Canadian theologian and Jesuit priest, the Rev. Anthony A. Stephenson, 59. A former teacher at Oxford University, he has been professor of religion at Baptist McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, since 1963.

It was to the Anglican church that Stephenson turned. He said his reasons for leaving the Roman Catholic Church were “strictly theological and ecclesiastical.” He has no plans for marrying. Before receiving communion in Anglo-Catholic St. Thomas’ Church, Stephenson was asked three questions by Archbishop W. L. Wright: “Have you been baptized with water in the name of the Holy Trinity? Do you believe the Anglican church to be a branch of the one true, Holy, Catholic and Apostolic Church? Do you wish to be received into this church and submit to its doctrine and authority?”

The former Jesuit says he has not repudiated the Roman Catholic Church but feels like a “spiritual bigamist, in love with two churches at the same time.”

J. BERKLEY REYNOLDS

Stew At Drew

A nine-man committee headed by noted Methodist layman Charles C. Parlin holds its first meeting at Drew University this week to mediate a dispute that climaxed in the January firing of theological Dean Charles W. Ranson.

The issue on the surface is a clash between two strong personalities, Ranson and university President Robert F. Oxnam, son of the late, controversial Methodist Bishop G. Bromley Oxnam. But the underlying question appears to be the place of seminary education within a university. Many seminaries today are seeking closer ties with universities; Drew is a turnabout of the trend. The Madison, New Jersey, seminary (second largest of The Methodist Church) was there first, and the university started growing up around it in 1928. Now the seminary feels sidelined.

A year ago, Ranson proposed to Oxnam a special committee to “report and advise” Drew trustees on “ministerial education” policy. Some considered this a search for a separate channel, perhaps even a hint that the seminary’ should become a separate entity.

Since he became president in 1961, Oxnam has shown “indifference, if not hostility,” toward theological education, complains one teacher. Although the use of university funds and other resources is involved, this teacher sees the major problem as “a lack of any coherent policy regarding the theological school and its place in the university.” Adds another, “The president’s main interest is in the college. The seminary gets the slim end of it.”

When Ranson and his colleagues failed to get action from Oxnam on a planning committee, twenty-one of the twenty-two seminary staffers went over his head in December. They complained directly to trustees of a breakdown in “mutual confidence and communication.” Oxnam, in private, asked Ranson to quit, and Ranson asked for formal charges, which never came. Then last month Oxnam announced to the theological faculty that Ranson was through as dean (he retains a professorship). The Parlin committee is to choose a new dean and study the seminary program in general. But the faculty is up in arms over the firing, and students broke a century of calm to march to Oxnam’s house in protest.

Oxnam, 51, is Drew’s first lay president. He previously was president of Pratt Institute and had held several other university administrative posts. A lean, rather patrician man, he is on the executive committee of the World Methodist Council and other denominational agencies.

Ranson, a 63-year-old Irishman, was chosen dean in late 1964. He had been director of the Theological Education Fund, general secretary of the International Missionary Council (since merged into the World Council of Churches), and a veteran missionary educator and administrator in India.

Pike Case Erased?

The proposed inquiry into heresy charges against Episcopal Bishop James A. Pike may never come off. A special committee will weigh the degree of theological latitude allowable in the Episcopal Church. Religious News Service reported Pike as saying that in view of the appointment of the advisory group, he will not press his demand for a formal investigation of the heresy charges made publicly against him.

A Switch In ‘Time’

Time magazine got a new religion writer last month: Bruce Henderson, a Protestant who previously wrote on national affairs. He replaces John T. Elson, 35, a Roman Catholic who handled religion for five years and is now a senior editor with responsibility for the religion, education, theater, and cinema sections. Under a major expansion now in the works, Time probably will add a second person, from outside its staff, to specialize in religion.

Arnott Resigns At Berkeley

Capping a bitter controversy at Berkeley Baptist Divinity School (see Dec. 23, 1966, issue), Dr. Robert J. Arnott resigned as president to accept an appointment to the faculty of the Methodist-Disciples School of Theology at Claremont, California.

No Tolerance For Toplessness

Six leading New York City churchmen predicted that a court decision legalizing topless waitresses “will not be tolerated by the public.” Protestant Council President Norman Vincent Peale and Methodist Bishop Lloyd C. Wicke were among the churchmen calling on authorties to “take whatever steps are necessary as soon as possible.”