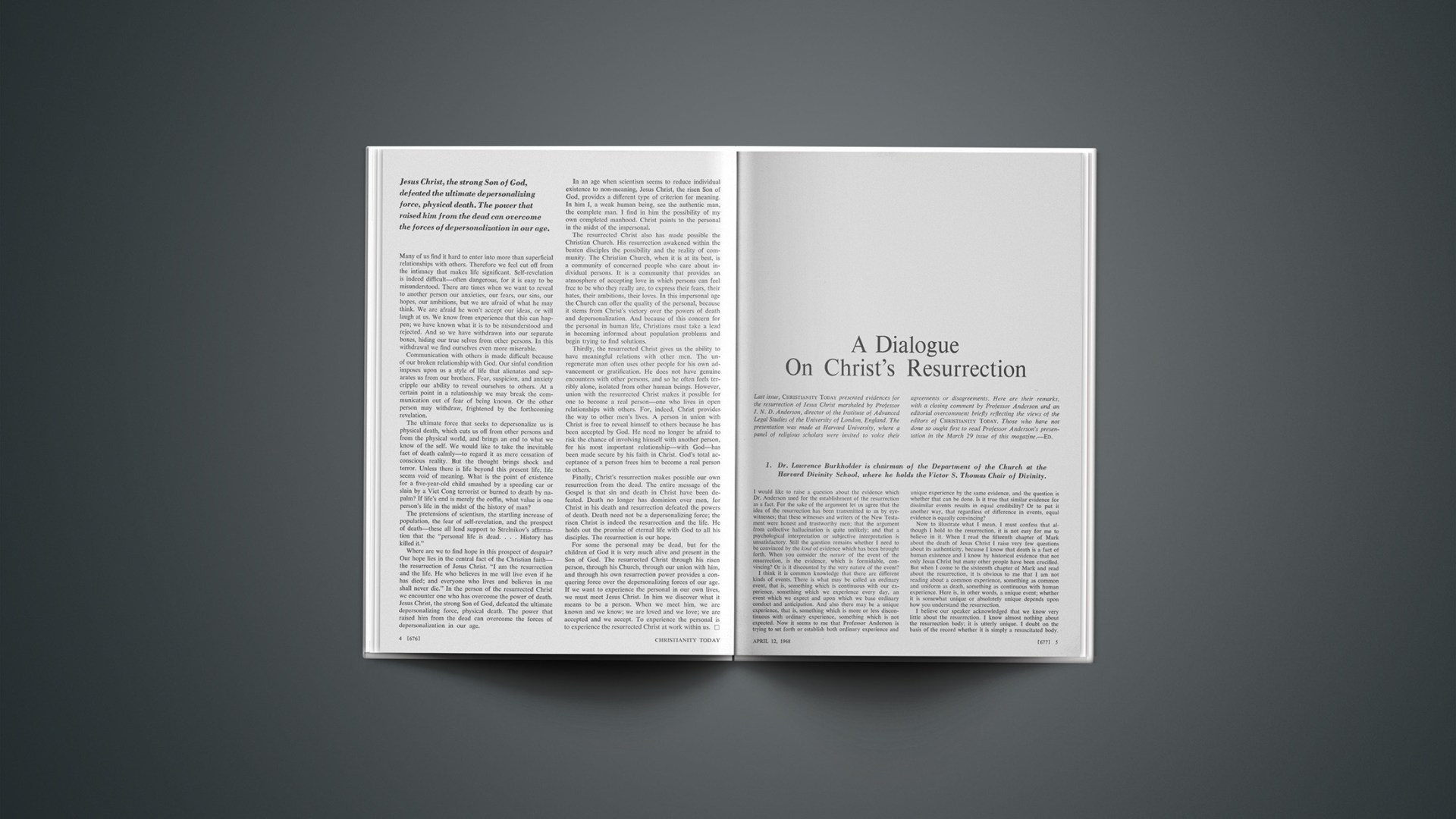

Last issue,CHRISTIANITY TODAYpresented evidences for the resurrection of Jesus Christ marshaled by Professor J. N. D. Anderson, director of the Institute of Advanced Legal Studies of the University of London, England. The presentation was made at Harvard University, where a panel of religious scholars were invited to voice their agreements or disagreements. Here are their remarks, with a closing comment by Professor Anderson and an editorial overcomment briefly reflecting the views of the editors ofCHRISTIANITY TODAY.Those who have not done so ought first to read Professor Anderson’s presentation in the March 29 issue of this magazine.—ED.

1. Dr. Lawrence Burkholder is chairman of the Department of the Church at the Harvard Divinity School, where he holds the Victor S. Thomas Chair of Divinity.

I would like to raise a question about the evidence which Dr. Anderson used for the establishment of the resurrection as a fact. For the sake of the argument let us agree that the idea of the resurrection has been transmitted to us by eyewitnesses; that these witnesses and writers of the New Testament were honest and trustworthy men; that the argument from collective hallucination is quite unlikely; and that a psychological interpretation or subjective interpretation is unsatisfactory. Still the question remains whether I need to be convinced by the kind of evidence which has been brought forth. When you consider the nature of the event of the resurrection, is the evidence, which is formidable, convincing? Or is it discounted by the very nature of the event?

I think it is common knowledge that there are different kinds of events. There is what may be called an ordinary event, that is, something which is continuous with our experience, something which we experience every day, an event which we expect and upon which we base ordinary conduct and anticipation. And also there may be a unique experience, that is, something which is more or less discontinuous with ordinary experience, something which is not expected. Now it seems to me that Professor Anderson is trying to set forth or establish both ordinary experience and unique experience by the same evidence, and the question is whether that can be done. Is it true that similar evidence for dissimilar events results in equal credibility? Or to put it another way, that regardless of difference in events, equal evidence is equally convincing?

Now to illustrate what I mean, I must confess that although I hold to the resurrection, it is not easy for me to believe in it. When I read the fifteenth chapter of Mark about the death of Jesus Christ I raise very few questions about its authenticity, because I know that death is a fact of human existence and I know by historical evidence that not only Jesus Christ but many other people have been crucified. But when I come to the sixteenth chapter of Mark and read about the resurrection, it is obvious to me that I am not reading about a common experience, something as common and uniform as death, something as continuous with human experience. Here is, in other words, a unique event; whether it is somewhat unique or absolutely unique depends upon how you understand the resurrection.

I believe our speaker acknowledged that we know very little about the resurrection. I know almost nothing about the resurrection body; it is utterly unique. I doubt on the basis of the record whether it is simply a resuscitated body. Rather, I would be inclined to accept the Apostle Paul’s view that it is a spiritual body as a result of a transformation. But what transformation really means I don’t understand; all I can say is that something is changed and changed drastically. I must confess that the resurrection is enigmatic to me. Now the question is, can I believe in something which is utterly unique, which is so different from ordinary experience? I can believe in the Battle of Waterloo; I can believe in the death of Caesar; I can believe a lot of other things on the basis of historical evidence. But can we use similar evidence to establish a unique event such as the resurrection?

I suppose what lies behind this question is really the argument which was set forth by Hume, that awful man, many years ago, which I have pondered and have been wrestling with all these years, and to which I haven’t really been able to reply satisfactorily. He says that no testimony is sufficient to establish a miracle unless it is of such a kind that its falsehood would be as miraculous as, or more miraculous than, the fact it endeavors to establish. What he is really saying is that belief is justified by probability, and that probability is based upon or synonymous with uniformity in nature. We are justified, in other words, in believing that which is uniform to our experience of nature; but when it comes to something which is so utterly unique, so discontinuous with ordinary human experience as a miracle—not only the miracle of the resurrection but any other miracle—we just have no right to accept it, to believe it. Another way of putting it is this: Which is more likely to have happened, that Jesus was raised from the dead or that the disciples just made a mistake? Which is more likely?

Now I think that in all candor and honesty, those of us who are Christians will have to admit that a lot of people are under the pressure of this argument, I myself am. It is another way of presenting what is sometimes referred to as the modern scientific attitude, based upon the uniformity of nature: miracles just don’t happen. I think it is only fair to say that a good many New Testament scholars do not go through all the exercise which we have had tonight because they don’t see that it is necessary. It just didn’t happen. It couldn’t have happened! And so therefore they are likely to take a mythical or psychological interpretation in view of the philosophical impossibility of an event of this kind.

I must confess that I have been influenced by this line of argument and I have wrestled with it for a long time. But another line of thinking is beginning to assert itself in my own experience, and that is the fact of uniqueness. Not so much the fact of uniqueness in nature, which I’m not even enough of a scientist to understand, though I hear that there is something like the indeterminate in nature. Rather I am referring to the uniqueness of historical events. Every historical event is to some extent or in some way unique. There are some historical events which are very unique, so much so that the first time we hear about it we are inclined, as good Humeans—as many of us are—not to believe it. But I must say that I’m beginning to feel the limitations of Hume. He seems to be imposing something on me which runs counter to a certain area of experience, that is, my experience with the unique. He is limiting the possibility of accepting what in later times and events I find to have been a fact. He is telling me I really can’t believe anything unless it corresponds to past experience. But I find myself increasingly refusing to predict the future. I find myself becoming much more modest when it comes to saying what is possible and what is not possible, what may happen in the future and what may not happen. And this same modesty is beginning to take the form of a reluctance on my part to say what could have happened in the past and what could not have happened. In other words, just as I have been forced at a certain stage of my thinking to come to terms with uniformity, with Hume, I am now becoming much more conscious of the unique in history. I am looking for some kind of a philosophical way by which to understand, to accept, and to believe the unique, particularly the historical unique.

Now, if I can think, then, that the resurrection not only was an event in nature but also pertains to the realm of history, and if I may at the same time conclude that the uniformity of nature is not absolute, and that the uniqueness of history including the resurrection is not absolutely unique—and if it were absolutely unique you couldn’t know anything about it at all—then it seems to me I have some right at least to be open to the possibility that something may have happened which by analogy we call the resurrection. So this leaves it a possibility. But I must confess that this is where I begin as a Christian and as a theologian. I find in this the possibility of thinking in terms of the resurrection and building up some kind of a theology in which the resurrection is very important. This is not the occasion to spell it out, but I feel I have the philosophical freedom to countenance the possibility of the resurrection and to build a theology and a faith in which it is a starting point.

2. Dr. Harvey Cox is associate professor of church and society, Harvard Divinity School; previously he was professor of theology and culture at Andover Newton, and chairman of the Boston chapter of the Americans for Democratic Action.

A person whose field it is to examine the credentials of the New Testament documents, their dating and their significance, might raise one or two questions about the presentation we heard. I think one might argue that it is possible, contrary to Dr. Anderson’s perspective, to separate the issue of the empty tomb from the issue of the reality of the resurrection. If one would examine each of the witnesses that he introduced early in his talk—Paul, Mark, and Luke—one would find that the latest of these witnesses, namely Luke, does mention the empty tomb. One would find that the early witness, Paul, does not mention it at all, and that there is some question in the mind of critical scholars whether Mark mentions it. The Gospel of Mark has two endings, one of which is later. The second ending does go into the empty-tomb story; the first does not. So that of these three witnesses there is at least some question. And I must indicate my difference of opinion with Dr. Anderson about why the Apostle Paul does not mention the empty tomb. I find it very unconvincing that he doesn’t mention it because it was simply common knowledge. I would believe rather that he doesn’t mention it because he didn’t know about it; that this was an interpretation of the resurrection which grew up much later and that at the time Paul wrote his epistles the stories about the empty tomb were not yet being circulated. Now there is no way to settle that dispute between Dr. Anderson and myself, and his opinion about why the Apostle Paul doesn’t mention it is probably as good as mine. I want to emphasize, however, that the reality of the resurrection, which I believe in, to me can be separated from the historical evidence about the empty tomb, which I find rather unconvincing at certain points.

You notice also that the heavy reliance that Dr. Anderson placed on the Gospel according to John later on in his talk. The description of the position of the grave clothes and the napkin and so on comes from a witness who is very, very late indeed; in fact, there are some scholars who believe that the Gospel of John was written in the second century A.D., a dozen decades after the events in question. Here we would have to raise the whole issue, I suppose, of hearsay evidence, about which a lawyer would know more than I do. In other words, the witnesses used here are of very mixed credibility, and while Dr. Anderson did establish the credentials of the first three witnesses early in his talk, he made no effort to establish the credentials of other witnesses he called upon later. As far as the empty-tomb stories are concerned, I would want to stick rather closely to the earliest testimonies, and here they simply are not mentioned.

The whole attempt to establish the reality of the resurrection in this way is a little disturbing to me. It smacks a bit of the uncanny, of the detective-novel approach to something which to me is neither establishable or destroyable on that basis. And, in fact, at the end of his talk Dr. Anderson himself said that the real evidence for the resurrection is somehow the experience of the person who meets or encounters the living God known through the revelation of Jesus Christ. I would want to say that in my own experience this is where I would begin to talk about the reality of the resurrection. I don’t think we’re talking here about a resuscitated corpse, and I’m glad that Dr. Anderson pointed out that this was a body described even in these sources as one that came through doors and had other characteristics not attributable to ordinary bodies. I do not believe we’re talking about an individual or social hallucination. Rather, I believe that the reality of the resurrection has to do with the beginning of a whole new era in human history and human experience, an era which is still open and has not yet finished.

All of us know that when we try to think about the resurrection of Jesus we often come to an impasse, and I would predict that at the end of this evening most of us will still probably be at that impasse. We also know that when we try to think about the very beginning of all things, the creation, or whatever it was, we come to the edge of our capacity to think or even to imagine; and when we try to think about the end of all things, after we’re gone and all that we know or can think about is gone, we also come to a kind of edge. I think what the Christian faith is saying is that this deep mystery which is at the beginning and at the end of all human existence is the mystery which was present in the life of Jesus of Nazareth, and that this mystery tells us that history is a place which is deeply mysterious, and yet that the mystery which surrounds all of us is a mystery which expresses itself through love and concern about man and about man’s place in this great mysterious cosmos.

It is not an accident and it is not unimportant that what we’re talking about at the center of the Christian Gospel is the life and death and resurrection of a man—not of an animal, not of a whole people, but of a particular human being whom Christians hold to be just as ordinary and just as human as you and I are. This signifies to me that the whole universe with the deep mystery in which it is imbedded focuses on and has something to do with the mystery of human existence itself. Jesus was an ordinary man, and to deny that is heresy; yet Jesus was the one in whom a whole new eon of human history began. And I do not believe that we can really understand or appreciate the meaning of the resurrection until we enter into this history ourselves. I don’t believe that we can simply be persuaded, even by as eloquent a presentation as we have heard this evening, of the reality of the resurrection unless we are willing ourselves to participate in that reality as it works itself out in the human history around us. And this means that to meet the same mysterious presence who was present in Christ and who was at the beginning and at the end is to know something about his life as well as his death and resurrection. To me it is very important that that life was spent identified with and in company with the poor, the rejected, the despised, the sick and the hurt people of his time I personally do not believe that we will have any personal experience of the deep mystery we’re discussing this evening until we are ready to identify our lives with these people in our time. Then and only then I think do we have the kind of experience on the basis of which we can talk about the reality of the resurrection.

I’m grateful, let me say again, for Dr. Anderson’s presentation. I found it about as persuasive as any presentation I have ever heard on the evidence of the resurrection. But I’ve read many books on one side and many on the other, and it rather seems to me at this point that arguments of this type about the resurrection are a little like arguments for the existence of God. They are very persuasive to people who already believe in God, but they rarely persuade anyone to believe in God who didn’t believe in him before reading the arguments. I think what we can say, and say for sure, is that for those who believe in the resurrection there is certainly no good historical evidence that it didn’t occur. But I believe that as those who are stuck forever, perhaps, or at least for our time, with the kind of Humean mark on our brow described by Professor Burkholder, we will have to live the rest of our lives both with the affirmation that in some way the Christ lives among us and with the gnawing doubt that this really isn’t possible. If we want to escape this kind of ambiguity, we are looking for a perfection which will not be available to us in this life. So I suppose my contribution would be the contribution of that young man in one of the Gospels who when he was confronted with Jesus said, “I believe, O Lord; help thou my unbelief!”

3. Dr. Wolfhart Pannenberg, professor of systematic theology at the University of Munich, Germany, studied under Barth and Jaspers, and has been concerned primarily with questions of the relation between faith and history. With a small group of dynamic theologians at Heidelberg, he has been forging a theology that considers its primary task the scrutiny of the historical data of the origins of Christianity.

I first have to admit that I find myself in basic agreement with the main points of what Dr. Anderson pointed out in his lecture. It’s not easy for theologians today to admit such a position. That may seem somewhat queer, but it is really the situation. One is much better received if he takes an extremely critical attitude toward the New Testament texts and toward Christian tradition. This is a psychological element in contemporary theological discussion. It is an extreme temptation for a theologian today to take an exaggeratedly critical position over against certain points in the history and the tradition of the Christian faith. If one does not do so, one is very easily identified with a group of fundamentalists and of uncritical thinkers, and nobody, I think—or at least not the majority of men in the academic community—would like to be identified with uncritical thinkers. Nevertheless, I admit that I agree with the basic points of Dr. Anderson’s presentation, though not wholly with the form of his argument, as will be shown by what I have to say.

I think the most sophisticated point a student has to learn at the university is that he has to be critical, but critical even over against the critics, you see. That must not mean that he has to return to a precritical attitude, but it’s a very difficult thing to be critical over against all sides.

Let me first number certain points of agreement. First, I agree with Dr. Anderson’s statement that the Easter story is of the utmost importance for the Christian faith. Paul says in First Corinthians 15 that the Christian proclamation would be empty if Jesus were not risen from the dead. That seems to be very obvious; yet there are many attempts to evade this point today. And these attempts have very obvious reasons—it does fit so badly, perhaps not so much into the twentieth-century scientific outlook, but into the traditional scientific outlook that developed from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. How could this event be possible at all? The argument of Hume is a very important example for this line of argument. So it is very understandable that theologians try to bracket the question of the resurrection of Jesus in understanding the reliability of the Christian faith. But intellectual honesty requires one to say that from the perspective of early Christianity, the question of the resurrection of Jesus is indeed the basic question of the Christian faith. It is hard to see what justification could be given for one to remain a Christian if he felt that the resurrection simply didn’t take place.

Further, I agree with Dr. Anderson that whether the resurrection of Jesus took place or not is a historical question, and the historical question at this point is inescapable. And so the question has to be decided on the level of historical argument. How hard this may be, and how dearly we would like to get to another level—especially to the level of personal experience, because this seems to be so much closer. Now, that personal experience has a share in the discussion of that question is undeniable, and in this point I can agree with Dr. Cox and in another sense with Dr. Burkholder. It is very important for the way historical questions are treated whether one agrees with Hume that, because of the uniformity of nature, such extremely unique events simply couldn’t take place, given any amount of evidence, or whether one has a general understanding of reality as marked by historical uniqueness, as we heard from Dr. Burkholder, or as marked by the character of the mysterious. The general attitude toward an understanding of reality is indeed very influential in assessing historical questions of all kinds, and so of course of this kind too. But this attitude toward reality does not settle the historical question. It is a presupposition, and one must try to keep the presupposition as open as possible, and not to make a dogmatic prejudgment. The question as such whether something happened or not at a given time some thousand years ago can be settled only by historical argument, even if we must admit that historical argumentation is often rather weak and can attain only some degree of probability.

Now to go into the particularities, I first agree that the appearances to the apostles are to be regarded as historical, and I think it is widely accepted among contemporary New Testament scholars that appearances to the disciples and Paul indeed took place. We are not dealing with later legend which would have no connection with the people to whom those experiences were attributed. But, of course, the real question is: In those appearances what happened to the disciples and to Paul? And this remains an open question, even if one admits that there were appearances.

The next point I must agree with concerns the tradition of the empty tomb. On this point, of course, prejudgments have been most influential even among theologians in the discussions of whether the tomb of Jesus was empty or not. And—not only because of those prejudgments, but because of the literary character of the key text, Mark 16—it is widely denied today among New Testament scholars that the story we read in Mark 16 of the finding of the empty tomb of Jesus is historical. It has widely been denied because the text is a Hellenistic text: not only is it written in Greek language, but a number of the conceptions in this text are of a Hellenistic character too. And that means that at least the final form of the tradition we have in Mark 16 was formulated a good while after those events that took place maybe in Palestine. So the whole Bultmannian school regards Mark 16, and all the accounts of the empty tomb that follow in the other Gospels, as later Hellenistic legends. I disagree with this, but thereby I disagree with the predominant judgment of contemporary exegetical research.

For my contrary understanding I have two main reasons. First, no early proclamation of the resurrection of Jesus in Jerusalem would be conceivable without safe evidence of the empty tomb on both sides, Christian and Jewish. The whole tradition, everything we know about the first situation of Christianity in Jerusalem, the place of Jesus’ death, would have to have been different had there been a disagreement among Christians and non-believers in the Jerusalem Jewry regarding the emptiness of the tomb. The resurrection of Jesus was imaginable in Jewish thought of that time only in a bodily form connected with the emptying of the tomb. The early proclamation of the resurrection of Jesus would hardly be conceivable if this proclamation could be countered, could be opposed, by showing the tomb of Jesus still untouched, or by arguing where the body was placed, or by arguing that nobody knew about the tomb of Jesus.

My second reason is that we know of no protest in the early Jewish polemics against the assertion of the empty tomb in the Christian proclamation. I think the Jewish anti-Christian polemics of early times had every reason to preserve information about the tomb of Jesus if this had been left intact. But the fact is that the Jewish anti-Christian polemics agree with the Christians that the tomb was empty; only the explanation of the emptiness is very different. I think this argument is very strong.

Now as a corollary I come to the silence of Paul. The silence of Paul concerning the empty tomb is really a very strong opposing argument, because Paul is the earliest witness we have in the New Testament. But one then has to show that in contemporary Jewish thought there existed a possible understanding of a resurrection without an emptying of the tomb, before one can interpret Paul as asserting belief in the resurrection but not implying self-evidently that the tomb was empty. And one also has to establish that Paul in his thought stood in relation to those Jewish circles that had a conception of the resurrection that does not require an empty tomb. But these two requirements have not been met. And as long as they are not, I think we will have to stay with the assumption that Paul, in speaking of the resurrection as a Jew of his time, implied that the tomb was empty. At this point I see no way out.

Now there are a number of points at which I disagree with Dr. Anderson, and about them I must be brief. First, I do not think that the evidence for the resurrection of Jesus primarily rests on the gospel accounts; I think it rests rather on First Corinthians 15—actually that was the first witness of Dr. Anderson, too, and this is valid concerning the appearances of Jesus. In the gospel texts we have to realize a heavy influence of apologetic motivation, and of at least legendary elements—not that whole stories in the Gospels are inventions, but that there are a good number of legendary elements, and those texts cannot be taken at face value. For example, there is an increasing emphasis—the later the text—on the bodily, almost miraculous character of the resurrected one. Luke speaks of Jesus preparing and eating fishes to demonstrate the bodily character of his appearance. This is completely against our first and oldest witness, namely Paul, who says that flesh and blood cannot inherit the kingdom of God because of the transformation that is involved in the resurrection, and who certainly understood the resurrection hope of the Christian as parallel to what he experienced as the reality of the resurrected Lord. And another legendary element: the disciples increasingly are connected with the tomb, while in the first account in Mark 16 the disciples are not connected with the tomb. The later the text, the more it tries to bring the disciples in greater relation to the tomb of Jesus. These are the main critical reservations I have about Dr. Anderson’s way of argumentation. Nevertheless I agree with his main points.

DR. ANDERSON’S RESPONSE

I am very grateful to the commentators for the kind things they said about my presentation. I don’t altogether agree with their attitude toward the evidence, even as they don’t altogether agree with mine. To begin with, I have a different view about the records. Take what Professor Cox said about the Gospel according to St. John. Since I am no theologian, I am being very bold, but I would say that the evidence that this was written by the end of the first century is extremely strong. I refer you to the writings of the late Archbishop William Temple; still more, perhaps, to the massive commentary of Professor Dodd, which shows—I should have thought conclusively, whatever one’s view may be on other points he makes—that a great deal at least of the Fourth Gospel goes back to a Palestinian source as early as the Synoptic sources. And as for the testimony of Peter, I rely in part on the commentary of Dean Selwyn.

With regard to Professor Pannenberg’s comment about the fish eaten by the risen Christ, I interpret that differently. I would say that this was not intended in any sense as a proof that he had an ordinary resuscitated human body. I don’t believe anything of the sort. I certainly do not believe that the transformed body of the risen Christ required food. I would suggest that he ate a piece of fish simply because the disciples might easily have concluded after his disappearance that they had seen a mere apparition, but to see before them the leftovers of the fish would be the most convincing proof that the experience was of an objective fact. I was grateful for Professor Pannenberg’s extremely interesting remarks about the empty tomb. This was probably because I don’t like to separate different parts of the evidence for the resurrection. If part can, perhaps, be explained on rationalistic grounds, this is unconvincing to the lawyer, at least unless that explanation fits all the evidence.

Professor Cox suggested that those who believe will, of course, go on believing, and that those who don’t believe will be left in a fog as they were before. That is not my experience. I have seen men and women who didn’t believe come to faith—many of them; I could introduce you to them tonight. I simply do not believe this gulf between belief and unbelief is impassable. Professor Cox suggested—though I think he misinterpreted me here—that I myself had said that personal experience was the basic proof. With respect I say that I didn’t. If the basic proof were personal experience, we might be deluded. I agree with Professor Pannenberg that the basic proof is historical. But I believe that the historical evidence is confirmed in the experience of believers. We have heard a good deal about a unique event, and certainly I believe it was a unique event; but I believe it concerned a unique person. I believe he was human indeed, but also divine.

May I end with one other point? In a certain university city in England one of the local clergy was in the habit of calling together, once a month, a discussion group of senior members of the university after evening service on Sunday, to talk in a completely uninhibited way about the pros and cons and the evidence for Christianity. Once when I happened to be in the city he asked me to go and talk to this group about the evidence for the resurrection; this would be followed by their usual kind of uninhibited discussion. In the course of this discussion, our host turned to a professor of philosophy who was not a Christian and said, “Well, Professor so-and-so, will you tell us quite frankly what you thought about Anderson’s treatment of the evidence for the resurrection?” He said, “Yes. When Anderson was dealing with the alternative views which have been put forward by one and another to try and explain away or give some rationalistic interpretation of the Easter story of the tomb and the resurrection appearances, I would agree with him that none of these is convincing, that none is persuasive. But all I can say is [and this comes back to Hume, I suppose] that if someone feels that he cannot believe in the resurrection, he will shrug his shoulders and say, ‘Well, I can’t square this with the evidence, but it cannot have happened like that.’ ” And I said to him, “Professor, may I paraphrase what you have just said? Surely what you have just said is this, that if a man or a woman doesn’t want to believe in the resurrection, and insists on some a priori ground that he cannot believe in the resurrection, then he won’t. I entirely agree with you. But it will not be because of the evidence; it will be in spite of the evidence. In other words, it won’t be on exclusively intellectual grounds; it will also represent, in some degree, a moral decision.” And he said, “I think that may be true.”