No one connected with the North American overseas missionary ministry of the churches can afford to overlook the statistical evidence that continues to pile up indicating that ecumenical agencies and church-unionized groups suffer from missionary attrition. The data runs directly counter to the often heard claim that ecumenism makes witness more effective.

In 1938 the Interpretative Statistical Survey of the World Mission of the Christian Church appeared. Now, thirty years later, the Missionary Research Library has published its eighth edition of North American Protestant Ministries Overseas. The comparisons are very revealing.

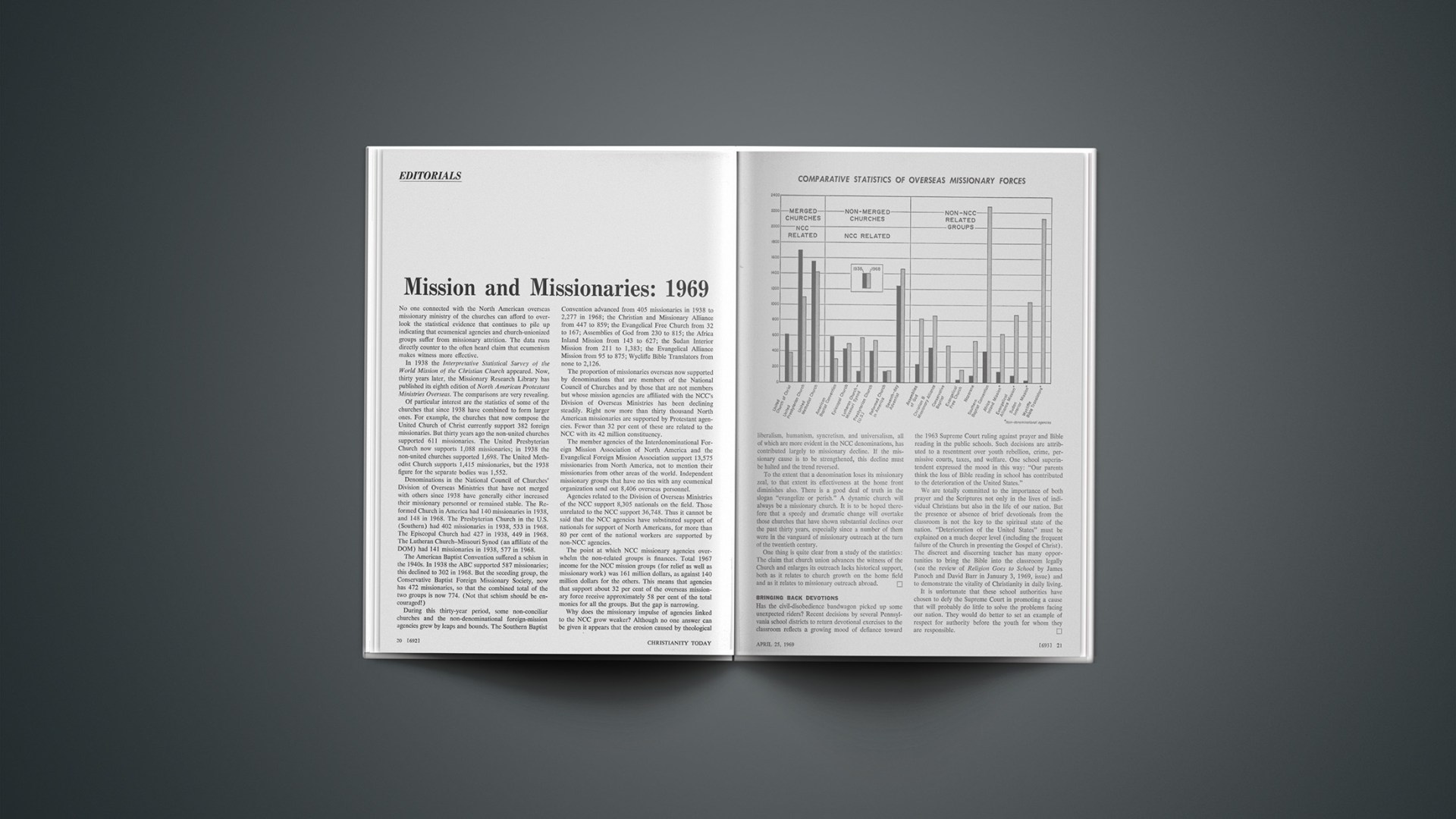

Of particular interest are the statistics of some of the churches that since 1938 have combined to form larger ones. For example, the churches that now compose the United Church of Christ currently support 382 foreign missionaries. But thirty years ago the non-united churches supported 611 missionaries. The United Presbyterian Church now supports 1,088 missionaries; in 1938 the non-united churches supported 1,698. The United Methodist Church supports 1,415 missionaries, but the 1938 figure for the separate bodies was 1,552.

Denominations in the National Council of Churches’ Division of Overseas Ministries that have not merged with others since 1938 have generally either increased their missionary personnel or remained stable. The Reformed Church in America had 140 missionaries in 1938, and 148 in 1968. The Presbyterian Church in the U.S. (Southern) had 402 missionaries in 1938, 533 in 1968. The Episcopal Church had 427 in 1938, 449 in 1968. The Lutheran Church-Missouri Synod (an affiliate of the DOM) had 141 missionaries in 1938, 577 in 1968.

The American Baptist Convention suffered a schism in the 1940s. In 1938 the ABC supported 587 missionaries; this declined to 302 in 1968. But the seceding group, the Conservative Baptist Foreign Missionary Society, now has 472 missionaries, so that the combined total of the two groups is now 774. (Not that schism should be encouraged!)

During this thirty-year period, some non-conciliar churches and the non-denominational foreign-mission agencies grew by leaps and bounds. The Southern Baptist

Convention advanced from 405 missionaries in 1938 to 2,277 in 1968; the Christian and Missionary Alliance from 447 to 859; the Evangelical Free Church from 32 to 167; Assemblies of God from 230 to 815; the Africa Inland Mission from 143 to 627; the Sudan Interior Mission from 211 to 1,383; the Evangelical Alliance Mission from 95 to 875; Wycliffe Bible Translators from none to 2,126.

The proportion of missionaries overseas now supported by denominations that are members of the National Council of Churches and by those that are not members but whose mission agencies are affiliated with the NCC’s Division of Overseas Ministries has been declining steadily. Right now more than thirty thousand North American missionaries are supported by Protestant agencies. Fewer than 32 per cent of these are related to the NCC with its 42 million constituency.

The member agencies of the Interdenominational Foreign Mission Association of North America and the Evangelical Foreign Mission Association support 13,575 missionaries from North America, not to mention their missionaries from other areas of the world. Independent missionary groups that have no ties with any ecumenical organization send out 8,406 overseas personnel.

Agencies related to the Division of Overseas Ministries of the NCC support 8,305 nationals on the field. Those unrelated to the NCC support 36,748. Thus it cannot be said that the NCC agencies have substituted support of nationals for support of North Americans, for more than 80 per cent of the national workers are supported by non-NCC agencies.

The point at which NCC missionary agencies overwhelm the non-related groups is finances. Total 1967 income for the NCC mission groups (for relief as well as missionary work) was 161 million dollars, as against 140 million dollars for the others. This means that agencies that support about 32 per cent of the overseas missionary force receive approximately 58 per cent of the total monies for all the groups. But the gap is narrowing.

Why does the missionary impulse of agencies linked to the NCC grow weaker? Although no one answer can be given it appears that the erosion caused by theological liberalism, humanism, syncretism, and universalism, all of which are more evident in the NCC denominations, has contributed largely to missionary decline. If the missionary cause is to be strengthened, this decline must be halted and the trend reversed.

To the extent that a denomination loses its missionary zeal, to that extent its effectiveness at the home front diminishes also. There is a good deal of truth in the slogan “evangelize or perish.” A dynamic church will always be a missionary church. It is to be hoped therefore that a speedy and dramatic change will overtake those churches that have shown substantial declines over the past thirty years, especially since a number of them were in the vanguard of missionary outreach at the turn of the twentieth century.

One thing is quite clear from a study of the statistics: The claim that church union advances the witness of the Church and enlarges its outreach lacks historical support, both as it relates to church growth on the home field and as it relates to missionary outreach abroad.

Bringing Back Devotions

Has the civil-disobedience bandwagon picked up some unexpected riders? Recent decisions by several Pennsylvania school districts to return devotional exercises to the classroom reflects a growing mood of defiance toward the 1963 Supreme Court ruling against prayer and Bible reading in the public schools. Such decisions are attributed to a resentment over youth rebellion, crime, permissive courts, taxes, and welfare. One school superintendent expressed the mood in this way: “Our parents think the loss of Bible reading in school has contributed to the deterioration of the United States.”

We are totally committed to the importance of both prayer and the Scriptures not only in the lives of individual Christians but also in the life of our nation. But the presence or absence of brief devotionals from the classroom is not the key to the spiritual state of the nation. “Deterioration of the United States” must be explained on a much deeper level (including the frequent failure of the Church in presenting the Gospel of Christ). The discreet and discerning teacher has many opportunities to bring the Bible into the classroom legally (see the review of Religion Goes to School by James Panoch and David Barr in January 3, 1969, issue) and to demonstrate the vitality of Christianity in daily living.

It is unfortunate that these school authorities have chosen to defy the Supreme Court in promoting a cause that will probably do little to solve the problems facing our nation. They would do better to set an example of respect for authority before the youth for whom they are responsible.

Goodness, Truth, And Popcorn

A slot seen round the world swallowed a penny in a Broadway Kinetescope parlor on April 14, 1894, and permitted a patron a fifteen-second peep at pictures that moved. The experience itself was moving, and it was only the first of its kind. Soon a projector threw the motion onto a screen, and the experience—shared now—grew richer and more intense.

And still there was more to come—this time not from an inventor but from an artist, D. W. Griffith, who discovered the close-up. By featuring specific gestures, reactions, and even objects, the director controlled the development of the story and elicited the viewer’s laughter or tears. Audience involvement in filmed emotion peaked dramatically when Griffith’s Civil War story, The Birth of a Nation, provoked race riots.

But even Griffith’s artistry was not the apex of movies’ emotional intensity. A Russian director, Sergei M. Eisenstein, edited feeling into his movies; when he spliced into one scene several objects or gestures with symbolic value, the emotional impact—the suspense or shock, for example—of the whole was greater than that of any part. Eisenstein also edited time; when he prolonged tension or skimmed happiness fleetingly, viewers saw their own feelings made specific.

When sound and color and wide screens came to the movies, they too helped the viewer see a little more vividly and feel a little more intimately.

The movies’ successful achievement of vivid intimacy in the post-World War I era nearly spoiled them. Their newly rich stars, directors, and producers could afford divorces, drugs, and bootleg liquor, and shouted the fact on movie screens. Aspiring starlets who had been captivated by vicarious thrills in their hometown theaters deluged scandal-saturated Hollywood. There scores of them drowned in the high tide of debauchery. An outraged nation, trying to patch the hole in its moral fiber, demanded censorship, and the industry responded with its own regulatory board headed by Will H. Hays, a Republican who was also a Presbyterian elder. Under the Hays Office, movies did become “moral”—at least at the end of the seventh reel after the fun (read sin) had ended. When the depression deflated Hollywood’s high living, realism—often crudely explicit—took over the leading role. Something more like genuine reform came, finally, in 1934, when the Roman Catholic Legion of Decency, supported by many Protestants, proposed a Production Code that the industry accepted as financially expedient.

Throughout the industry’s seventy-five-year history, Christians have objected to the “wine, women, and wrong” of Hollywood and its product—often with good reason. Life pictured on the commercial movie screen is still rarely (if ever) the abundant life Christ promised, and many Christians believe they can live more fully in Christ by staying out of theaters. But movies appear firmly installed on the twentieth-century landscape—even on the living-room TV screens of devout believers.

The persuasive power of movies deserves healthy respect, not fear of seeing depraved deeds shown in living color with all the emotional intensity of the artist’s ability. Depravity, after all, is a state of being; it precedes and produces the sinful act. Long before Thomas Edison made moving pictures technically feasible, John Milton wrote in Areopagitica:

They are not skillful considerers of human things, who imagine to remove sin, by removing the matter of sin.… Though ye take from a covetous man all his treasures, he has yet one jewel left, ye cannot bereave him of his covetousness. Banish all objects of lust, shut up all youth into the severest discipline that can be exercised in any hermitage, ye cannot make them chaste, that came not thither so.

And he was only echoing words spoken centuries earlier by Christ himself:

Do you not see that whatever goes into a man from outside cannot defile him?… What comes out of a man is what defiles a man. For from within, out of the heart of man, come evil thoughts, fornication, theft, murder, adultery, coveting, wickedness, deceit, licentiousness, envy, slander, pride, foolishness. All these evil things come from within, and they defile a man [Mark 7:18, 20–23].

That, of course, is no license to wallow in muddy obscenity. Rather it is a challenge to discern between good and evil, between truth and error. Milton recognized the difficulty and the value of wholeheartedly embracing good and truth:

Good and evil we know in the field of this world grow up together almost inseparably.… He that can apprehend and consider vice with all her baits and seeming pleasures, and yet abstain, and yet distinguish, and yet prefer that which is truly better, he is the true warfaring Christian.

Goodness and truth are discernible in movies as love and sincere concern for others, as joy, as the beauty of creation, as justice, as honesty about man’s alienation and search for meaning in life. But the Christian will have to battle for truth and goodness at the movies (and at the bowling alley, the supermarket, the office). If he prepares properly for the fight—if he girds himself with truth, thinks about “whatever is true,” surrenders his emotions and will to the One who said, “I am the truth”—the Christian can emerge victorious.

Discharging God From The Army

How does one instill a sense of moral responsibility in men without referring to God or to any religious philosophy? United States Army chaplains could be confronted with this absurd problem if the American Civil Liberties Union has its way and a proposed Army policy is eventually put into effect. In response to an ACLU complaint, the Army was prepared to eliminate all references to God and religious philosophy in character-guidance courses required as a part of military training. It has always been understood that these compulsory courses, in accordance with the First Amendment, were to avoid teaching any particular religious tenets or doctrines, but the proposed prohibition of any references to religion or to God has touched off considerable controversy.

Such a policy would raise at least three serious questions. First, is there any meaningful basis for moral responsibility when God has been pushed out of the picture? To ask a chaplain to advocate the building of a strong moral character apart from any mention of God is like asking a contractor to construct a sturdy building while forbidding him to lay any foundation. Even if such training were to be taken out of the hands of the chaplains (which would be the only logical move if God is eliminated), the fact remains that no one can teach moral responsibility without some set of basic presuppositions that could be called religious. To ban God is to ban any justification for such instruction.

Secondly, what justification can the ACLU offer for its defense of human liberty if it denies the validity of any kind of religious philosophy as a part of the national life? Ironically, the very freedom so passionately espoused by the ACLU is rooted in the principle, clearly stated by the Founding Fathers, that man’s inalienable rights are derived from his being a creature of God. As Walter Lippmann has pointed out, “The liberties we talk about defending today were established by men who took their conception of man from the great central religious tradition of Western civilization, and the liberties we inherit can almost certainly not survive the abandonment of that tradition.…”

Thirdly, since the political life and spirit of this country were based on religious convictions, what legitimate basis is there for abandoning these convictions now under the pretense of upholding the Constitution? James Reston has put the question this way: “If religion was so important in the building of the Republic, how could it be irrelevant to the maintenance of the Republic? And if it is irrelevant for the unbelievers, what will they put in its place?”

This incident is only one of many attempts to remove God from our national life. Such a course leads not to liberty but to slavery. For proof, ask the man who lives in an atheistic society.

Original Sin And Roman Catholic Theology

Since Vatican II, Roman Catholic theology and theologians have been moving forward, backward, sideways, and up and down, not to say upside down. The recent publication of Herbert Haag’s book (translated from the 1966 German edition) Is Original Sin in Scripture? adds notably to the present confusion and highlights the Pope’s increasingly difficult task of maintaining the traditional theology of his church.

Haag’s answer to his question is simple: No, original sin is not to be found in Scripture. And in the opinion of Hans Küng, Haag gives “a courageous, clear, and convincing answer.” In the book certain conclusions, stated or unstated, emerge clearly: (1) Catholic catechisms, theology textbooks, and conciliar decrees are in error—and of necessity this means the pope is fallible and the magisterium of the church questionable; (2) infant baptism, designed to take away original sin, makes no sense and is superfluous since all men are born into this world good; (3) the Scriptures must be understood and interpreted in the light of current historical criticism and cannot be regarded as wholly trustworthy (thus Haag’s own appeal to Scripture loses its force); (4) we must come to terms with Darwinian evolution, which “lies in the background of this book.”

Even those who may welcome Haag’s unsettling opinions will be confused by one evident anachronism that defies not only logic but the Scriptures that Haag is supposed to use for establishing his case. He says that the Virgin Mary “did not need rebirth or the remission of sins,” though he professes distaste for the term “Immaculate Conception.” Indeed, he must dislike the term, for the simple reason that since all people are born into this world without original sin, then Mary was born into the world in a way no different from all other people. Yet all others sin but she didn’t. Why all should be disposed to sin and actually sin Haag does not say. Nor does he explain why God gave Mary the grace to remain sinless that he denied to all others. If Haag isn’t careful, he will come up with an explanation that could easily resemble the doctrine of original sin.

This book does not have either the nihil obstat or the imprimatur of the church—which leads one to suppose that the teaching is not acceptable to the church. What the Pope will do with his heretical teachers will be interesting to see. But what he cannot do, it seems to us, is prevent further erosion in his church by dissidents intent on noisily tearing down a theological structure erected so painfully across the centuries. In time the holy father may find himself cloistered in the Vatican defending a theology nobody believes and trying to lead a church that denies to him all the attributes essential to his leadership. Pope Paul is in deep trouble.

Finding A Collar That Fits

Two controversial churchmen are giving up their appointments and their clerical status. Dr. Nathan Wright, a leading black church figure who has headed urban work for the Episcopal Diocese of Newark, said “inner tension” prompted his decision. Monsignor Ivan Illich, whose Mexican study center was disowned by the Vatican, said the charges brought against him had made him a “notorious churchman.” Both seemed to realize that their inner convictions were incompatible with their ecclesiastical loyalties.

Fine. Such decisions reflect an integrity that is commendable whether or not one approves of what the clergy have been doing. These churchmen are a welcome change from those who work at cross purposes with the Church, yet continue to enjoy its benefits.

Particularly deplorable is the kind of threat that recently came from New York’s “Interfaith Citywide Coordinating Committee Against Poverty.” A clergy spokesman for this group told newsmen that unless the state legislature approves more welfare funds “we will have to support the positive use of violence.” Thanks a lot. Perhaps the churches that endorse such “ministries” ought then to be billed for the damages.