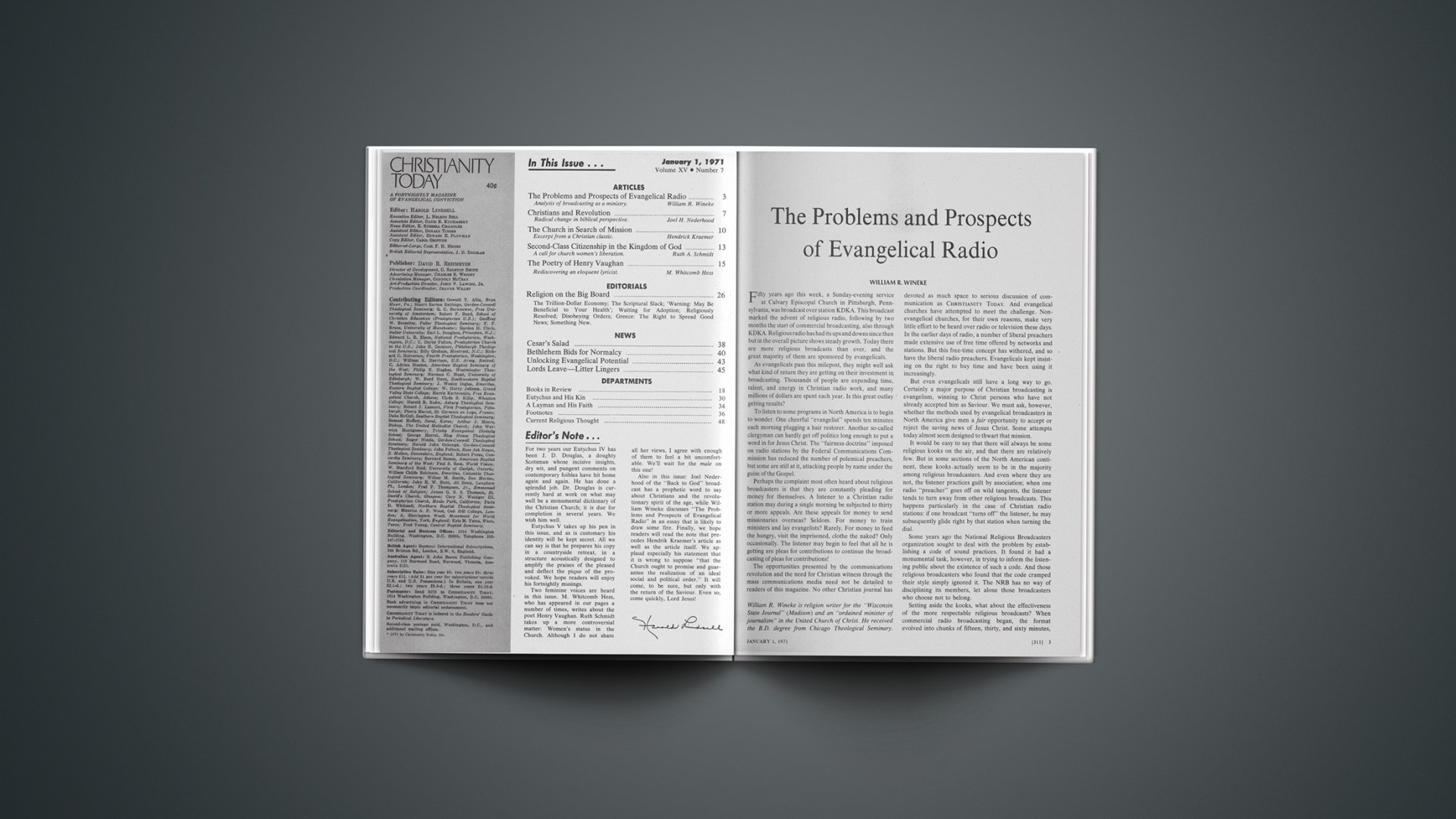

Fifty years ago this week, a Sunday-evening service at Calvary Episcopal Church in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, was broadcast over station KDKA. This broadcast marked the advent of religious radio, following by two months the start of commercial broadcasting, also through KDKA. Religious radio has had its ups and downs since then but in the overall picture shows steady growth. Today there are more religious broadcasts than ever, and the great majority of them are sponsored by evangelicals.

As evangelicals pass this milepost, they might well ask what kind of return they are getting on their investment in broadcasting. Thousands of people are expending time, talent, and energy in Christian radio work, and many millions of dollars are spent each year. Is this great outlay getting results?

To listen to some programs in North America is to begin to wonder. One cheerful “evangelist” spends ten minutes each morning plugging a hair restorer. Another so-called clergyman can hardly get off politics long enough to put a word in for Jesus Christ. The “fairness doctrine” imposed on radio stations by the Federal Communications Commission has reduced the number of polemical preachers, but some are still at it, attacking people by name under the guise of the Gospel.

Perhaps the complaint most often heard about religious broadcasters is that they are constantly pleading for money for themselves. A listener to a Christian radio station may during a single morning be subjected to thirty or more appeals. Are these appeals for money to send missionaries overseas? Seldom. For money to train ministers and lay evangelists? Rarely. For money to feed the hungry, visit the imprisoned, clothe the naked? Only occasionally. The listener may begin to feel that all he is getting are pleas for contributions to continue the broadcasting of pleas for contributions!

The opportunities presented by the communications revolution and the need for Christian witness through the mass communications media need not be detailed to readers of this magazine. No other Christian journal has devoted as much space to serious discussion of communication as CHRISTIANITY TODAY. And evangelical churches have attempted to meet the challenge. Non-evangelical churches, for their own reasons, make very little effort to be heard over radio or television these days. In the earlier days of radio, a number of liberal preachers made extensive use of free time offered by networks and stations. But this free-time concept has withered, and so have the liberal radio preachers. Evangelicals kept insisting on the right to buy time and have been using it increasingly.

But even evangelicals still have a long way to go. Certainly a major purpose of Christian broadcasting is evangelism, winning to Christ persons who have not already accepted him as Saviour. We must ask, however, whether the methods used by evangelical broadcasters in North America give men a fair opportunity to accept or reject the saving news of Jesus Christ. Some attempts today almost seem designed to thwart that mission.

It would be easy to say that there will always be some religious kooks on the air, and that there are relatively few. But in some sections of the North American continent, these kooks actually seem to be in the majority among religious broadcasters. And even where they are not, the listener practices guilt by association; when one radio “preacher” goes off on wild tangents, the listener tends to turn away from other religious broadcasts. This happens particularly in the case of Christian radio stations: if one broadcast “turns off” the listener, he may subsequently glide right by that station when turning the dial.

Some years ago the National Religious Broadcasters organization sought to deal with the problem by establishing a code of sound practices. It found it had a monumental task, however, in trying to inform the listening public about the existence of such a code. And those religious broadcasters who found that the code cramped their style simply ignored it. The NRB has no way of disciplining its members, let alone those broadcasters who choose not to belong.

Setting aside the kooks, what about the effectiveness of the more respectable religious broadcasts? When commercial radio broadcasting began, the format evolved into chunks of fifteen, thirty, and sixty minutes, and religious broadcasters adapted “services” to these lengths. For many years the radio was the center of home entertainment. Members of the family sat around the living room listening—for hours at a time. With the advent of television, radio had to find itself a new niche. Now people tend to listen to the radio only while doing something else, like driving, shaving, cooking dinner, or cleaning the house. They don’t stick close enough to the radio to follow long messages, so radio format developed into smaller chunks with little or no continuity between them.

But few gospel programs have kept pace. Their standard format is still the fourteen-minute sermon bracketed by hymns or gospel songs. That the continuation of this format drives away listeners is a theory apparently held by managers of secular stations, since many of them confine their religious broadcasting to the Sunday-morning ghetto—a time when they feel that only “religious” people will be listening anyway. Thus it may be argued that evangelical broadcasts are heard by those who have already responded to the Gospel, rather than by those who stand in need of its saving message, and their evangelistic impact is almost nil. But the theory is not altogether sound; non-churchgoers are likely to be home on Sunday mornings with time on their hands, and may tune in for lack of anything better to do.

The problem is compounded by owners of Christian radio stations who yield to the temptation to sell time to “medicine men,” far-out political types, and the like. Unfortunately, some of these radio speakers are bigoted and malicious, and their programs are little more than forums of obscurantism. Their effect is to nourish prejudices, comfort evil, and foster deceit. No doubt some preach a truncated Gospel sincerely, out of sheer ignorance. But whatever the cause, the effect is to repel intelligent people and mislead the unthinking.

What a tragedy—no, more than that, what blasphemy! As the commercials tell us, radio is with us everywhere. We hear it at the breakfast table, in the car, in the barber shop, and, since the appearance of transistor portables, increasingly on the streets. No medium has greater potential for communicating the Gospel to the man who does not attend church, does not read tracts, does not open the Bible.

Yet in response to some of what he hears paraded on the radio as Christian, he laughs! He does not laugh at the Gospel; he does not hear the Gospel. He laughs at the absurdity of people who think he can be persuaded by such a presentation. And it is sometimes well that he does, for what he has heard may be so far from the authentic Gospel that if he were to accept it he might tune out the real, overriding call of Christ that makes a man confront his entire existence and choose once and for all whether he will follow.

Probably little more can be done to eliminate obnoxious religious broadcasters. As long as they avoid outright slander and fraud, they have a right to be on the air. This is part of the price paid for a free society. (Some may be obliged to leave the air, however, if more quality programs are presented and supported.)

But what can responsible evangelical broadcasters do to enhance their own effectiveness?

One thing to keep in mind is that a great many people do listen to evangelical broadcasts as they are. They enjoy them and would complain if they were changed. Several hundred radio stations now carry evangelical programs for more than half their total air time, and most of these have begun operating within the past ten or fifteen years. That evangelical broadcasting is a big business is evidenced by the conventions of the National Religious Broadcasters, held each January in one of Washington’s big hotels. It is an influential industry that has the respect of many federal officials and communications experts.

One reason why evangelical broadcasting has as much appeal as it does is the current theological climate. Untold thousands of people, dismayed at the demise of biblical teaching in many mainline denominations, turn to radio for spiritual food. Dr. James M. Boice, voice of the “Bible Study Hour,” says mail analysis shows a surprising cross section of people being reached, many of whom have no other real contact with evangelical Christianity. “Often,” he says, “the people that the established church has failed—such as the shut-ins, the mid-city apartment dwellers, the inner-city poor, the geographically isolated—are the very ones who are ministered to by Christian radio.” Through radio there has been a continuing ministry to the lonely; many of them get very attached to the programs, so that radio preachers even get requests to conduct funerals.

Evangelical radio depends directly upon listener response. This makes it easy to determine whether people are listening. But it also makes change more difficult: if listeners do not like the change, they react immediately, and income promptly falls. Many evangelical broadcasters say they would be eager to try more imaginative programming if the constituency would go along.

On the other hand, the evangelical broadcaster must realize that a secular format is not necessarily the best means of communicating the Gospel. There are perhaps effective methods peculiar to the Christian message.

But what about the outsider who is accustomed to the secular format? How is he to be reached? Many evangelical broadcasters would admit they are not reaching people who are flatly hostile to the Christian faith. Most programs are not evangelistic in the pioneering sense. They do try to reach those on the periphery of the Church, those who know the Gospel but have not wholly committed themselves to it. But very few are trying to attract the attention of the religiously illiterate. Some evangelical leaders feel that a coordinated approach is needed for effective evangelism, and there may be a growing willingness to pool resources to this end.

Mass evangelistic appeal over radio is hindered by the trend toward specialization among radio stations and their audiences. One station programs only country music, another is all news, another is educational. But this can also be an asset. Dr. Joel Nederhood of the “Back to God Hour” is one who feels that specialization can be capitalized upon. “Our target is thoughtful people,” he says, “and we feel our approach is working. We are not interested in a mass audience.” One thing going for Nederhood is that the day of the orator seems to be coming back; while many liberals were lamenting what they saw as a growing lack of interest in preaching during the sixties, Martin Luther King was proving anew the power of the spoken word. At the same time, Billy Graham was preaching to more people than any other man in history.

Still, some changes are in order in evangelical programming. “More would be made if the supporting public would go along with them,” says Dr. Boice. “Religious broadcasters have always been on the horns of a dilemma: they desire to reach into a fresh, noncommitted audience with their message, yet they realize the peril of losing the financial support of their committed Christian public that resists any change. Consequently, while there is continual change, it is seldom dramatic, lest it jar the constituency.”

What is desperately needed is for younger Christians to capture the vision of gospel broadcasting and to learn to support innovation as sacrificially as their parents have supported traditional formats. The impact of those earlier programs is beyond question. To cite one outstanding example, many men are in the Christian ministry today as a result of the “Old Fashioned Revival Hour.”

There is a measure of innovative Christian broadcasting today, but few Christians in the West are aware of it. This is being done over short wave and beamed into countries where radio plays a much bigger part in people’s lives than it does in the United States and Canada. Many Christian radio programs overseas are having dramatic effects.

If new ground is to be broken on the domestic front, broadcasters will have to forge shorter and more subtle program formats. They will try to lead the listener to question his mode of living, rather than present him an answer to a question he is not yet asking. The listener may need to be shown Christianity not so much as something desirable but as something necessary. This kind of approach seems to be required for effective evangelism over the air waves today, and for the most part it will have to be made over secular stations.

The task of the Christian station is different. Except for a few uninitiated persons who happen upon the station, the audience of the Christian station already knows the purposes and biases of the broadcaster. This station’s job, then, is to build an audience, not just of those who already believe but of those who are willing to listen. The way to do that is to make the Christian station the most honest, the most reliable, and the most interesting sound on the broadcast band! How this is to be done is something that should inspire a great deal of thought and study and experimentation. But the goal of the Christian station should be to place “religion” into the total context of God’s sovereignty over human life.

If this high aim is widely adopted, the promise of Christian radio is great. With the advent of cable television and videotape cassettes (Electronic Video Recordings), the whole radio and television programming picture will probably begin to undergo drastic change within a year or two. The optimists among evangelical broadcasters see in the realignment new program opportunities and more time available, in both radio and television. Alert churches and Christian organizations should begin to explore the potential immediately.

Religious Radio 1921–1971

The first religious broadcast on a commercially licensed station took place on January 2, 1921, in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. It was the airing over station KDKA of the regular Sunday-evening church service from Calvary Episcopal Church. KDKA had begun broadcasting two months earlier with a program reporting the results of the election in which Warren G. Harding was chosen president of the United States.

Everything on the radio in those days was pioneering and experimental, and as KDKA staff members began to develop a program format they wondered what kinds of broadcasts might be appropriate for Sunday. One of them, Fletcher Hallock, was a member of the Calvary Church choir, and he suggested that perhaps his church might agree to broadcast its service. The station obtained the approval of the rector and the vestry and set up its apparatus in the chancel.

There seemed to be no great awareness in the church that history was being made. The sermon, the first ever preached on radio, was delivered not by the rector, the Reverend Dr. Edwin J. van Etten, but by his associate, the Reverend Lewis B. Whittemore. It had apparently been planned before the decision to broadcast was made that Whittemore was to preach that night. As he and the rector were waiting in the choir room just before the start of the service, Whittemore began wondering whether perhaps the service might prove to be a memorable one, and he suggested that van Etten should preach. Van Etten declined, however, and the service went on as previously arranged.

Not many people were equipped to listen to that service. And those who did have one of the first radio receiving sets with earphones were scattered far and wide. But the range of the station extended considerably beyond that of local stations today, so that listeners in distant places were able to hear. The Calvary Church bulletin noted that the service would be “flashed for a radius of more than a thousand miles through space.”

Immediately after the close of the broadcast, the church telephone began ringing as people from far and near called to express their appreciation. All that week the mail poured in. KDKA recognized the popularity of the church broadcast and added Calvary’s morning service to its regular Sunday programming.

Van Etten, though he had passed up the chance to become the first radio preacher, quickly sensed the potential of religious broadcasting and continued the radio ministry in the church. He left the church in 1940 to become the dean of St. Paul’s Cathedral in Boston. Whittemore went on to become bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Western Michigan. Both have since died. Now a bronze marker at the entrance to the church commemorates the first religious broadcast.

The idea of proclaiming the Gospel over the air waves spread quickly. Within a few years a number of evangelists had regular programs. Paul Rader in Chicago, R.R. Brown in Omaha, John Roach Straton in New York, and Donald Grey Barnhouse in Philadelphia were the best known of the pioneers. Moody Bible Institute began a radio station of its own in 1926. Liberal clergymen also began to be heard, but they gravitated toward cooperative efforts on time donated by stations and networks.

In the thirties a number of programs were started that are still being heard. These include the “Lutheran Hour,” which probably has a wider audience than any other regularly scheduled program in the world, the “Radio Bible Class,” the “Back to the Bible Broadcast,” and the “Back to God Hour” of the Christian Reformed Church.

Not all Christians were immediately enthusiastic about the use of radio. The Good News Broadcaster, in a two-part article on gospel radio, said that some saw it doomed to failure “because it operates in the very realm in which Satan is supreme. Is he not the prince of the power of the air?” A better-founded concern was that people were staying home from church because they said it was enough to hear the service on the radio. Van Etten, the rector of the church where it all began, expressed this anxiety in writing about radio in 1939. He compared the temptation to that presented to Israel by King Jeroboam:

Outside of Jerusalem Jeroboam instituted other centers for worship, one in Bethel and one in Dan. He invited people to go to these more accessible shrines, saying it was needlessly long and difficult for them to make the journey up to Jerusalem. This, I think, is the grave temptation made to many people in connection with radio religion. I believe that the next twenty years will see a swing of the pendulum in this matter. I believe we shall come to understand that listening to the radio cannot be a substitute for common worship.

Religious broadcasts probably did have an effect upon church attendance but secular programming took a higher toll. Some say it was the main reason for the decline of the Sunday-evening service. Television has made even more inroads.

The offsetting factor is that Christian broadcasting is having an impact of its own. Evangelical radio today is bigger than ever and shows no sign of any letup. Its “trade association” is the National Religious Broadcasters organization, which represents about 75 per cent of religious broadcasting. The Reverend Ben Armstrong, NRB executive secretary, estimates that half a million programs are aired each year over some 250 stations. More than twenty religious stations and program-producing organizations have annual budgets of at least $1 million. The annual NRB convention in Washington each year is the biggest evangelical media conclave and attracts hundreds each January.

What of the future? Communications satellites promise to bring the vision of a global village to reality. The scheduled launch this year of Intelstat IV will make available 6,000 voice circuits and twelve TV channels. The evangelistic potential should be obvious to alert believers.

On the ground, cassettes, which are revolutionizing home entertainment, will soon be providing not only sound but also pictures. Called EVR (for Electronic Video Recording), these cartridges will be played through a piece of hardware, already available, that is easily attached to a TV set. Europeans are promoting a plastic disc to rival the cassette. Either way, TV viewing will become more selective in the next few years, and if Christians are on the job, biblical options will become much more visible.

THE CATEGORICAL IMPERATIVE OPTION

Summons comes; awesome paradox:

Loud and clear, softly still;

Intuitive, extraneous suggestion,

Demanding compliance.

Lift the shoulders, shedding it;

Go out to play, in restive disregard;

Or react a little way, and with

A conscience quelled, taper off. Or make

Response as in responsible. The cause

Is always love, the current

Turning people on. Thus

The Kingdom quickens.

HELEN S. CLARKSON

William R. Wineke is religion writer for the “Wisconsin State Journal” (Madison) and an “ordained minister of journalism” in the United Church of Christ. He received the B.D. degree from Chicago Theological Seminary.