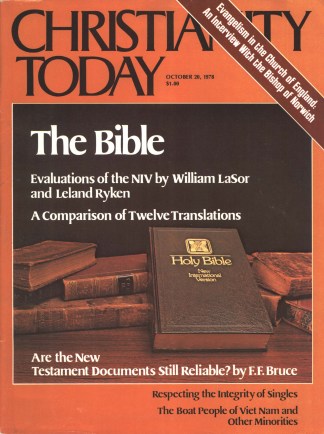

With all the publicity attending the completion of the New International Version, it is time to evaluate the wide range of English translations that we now have available. We give here some information about a dozen of them (only translations of both testaments are included, hence the omission of such New Testaments as Phillips). Every Bible-believer should be familiar with the following translations and should have copies of most if not all of them.

We still recommend “How To Choose a Bible” (December 5, 1975, issue, p. 7), by Gerald Hawthorne, a Greek professor and able preacher. Also see a major comparative review of three of the translations mentioned below (LB, MLB, NASB) in our October 8, 1971, issue, p. 16.

For further information on the translations we mention (plus many more) we highly recommend The History of the Bible in English: Third Edition by F. F. Bruce (Oxford), available in either cloth or paper binding. This new edition adds information on the translations issued since the 1961 and 1970 editions (which were confusingly titled The English Bible). Also worthwhile is So Many Versions? by Sakae Kubo and Walter Specht (1975, Zondervan pb). For a good collection of articles expressing various views on principles of translation see The New Testament Student and Bible Translation edited by John Skilton (1978, Baker or Presbyterian and Reformed pb).

The dates for each translation are for the first release of the whole Bible, which usually followed the New Testament by several years. Keep in mind that many translations are regularly revised so as to incorporate suggestions that were made for improving them.

KING JAMES VERSION (KJV, 1611, many publishers). This classic came at a British monarch’s approval of a resolution “that a translation be made of the whole Bible, as consonant as can be to the original Hebrew and Greek.” Most leading scholars of the day were involved. The original KJV, also known as the “Authorized Version,” included the Apocrypha and marginal notes reflecting uncertainties and variant readings in the manuscript. Its elegant prose was ideal for public reading. Updatings in spelling and renderings were made regularly into the 1800s, so the copies we have today are not identical with the 1611 edition. Despite intervening centuries and advances in linguistic and textual knowledge, the KJV retains a unique place in Christian hearts. Attempts to replace it by three authoritative translations, the Revised Version (1885), the American Standard Version (1901), and the Revised Standard Version (1952), proved futile. Annual sales of the KJV remain higher than any one of the recent translations. It is unlikely that any modern translation will ever dominate the field as the KJV has done for more than three centuries.

THE AMPLIFIED BIBLE (AB, 1964, Zondervan). This version was prepared under the auspices of the Lockman Foundation and Zondervan. Special notice goes to Frances Siewert who was researcher for the translation committee. The title comes from the alternative renderings and additional words supplied in the text itself (usually in parentheses or brackets) rather than in the margin or as footnotes. It is awkward to read the AB aloud and many critics feel that it loses both the readability of a freer translation and the precision of a stricter one.

GOOD NEWS BIBLE (GNB, 1976, American Bible Society, Collins, Nelson). The American Bible Society sponsored this runaway best seller (also known as Today’s English Version). The emphasis is on colloquial language, spoken rather than written. Some poetical passages do not fare well with such treatment, but many scholars agree with Walter Abbott that this translation is “not only clear and accurate, but also a masterpiece of modern linguistic study.” Many people think it combines the best attributes of readability while remaining close to the originals. A special advantage of this translation is the inexpensiveness of many of its bindings.

THE HOLY BIBLE IN THE LANGUAGE OF TODAY (Beck, 1976, Holman). The late William F. Beck was a Missouri Lutheran scholar who, proficient in Hebrew and Greek, spent much of his professional life translating the Bible, working through manuscripts and papyri to get the exact meaning of the original texts. The translation is simple and precise. Beck’s avowed goal was “to have God talk to the hearts of people in their language.” His work has been hailed as both faithful and readable. Beck died in 1966, just after completing his translation; fellow scholars edited the work through to publication.

THE JERUSALEM BIBLE (JB, 1966, Doubleday). This respected translation is a product of Catholic scholarship under the leadership of a British priest, Alexander Jones. The name comes because the annotations are translated from a French version prepared at a Dominican center for biblical studies in Jerusalem. Unlike previous English Catholic ventures, this translation was made from Hebrew and Greek rather than Latin. Naturally the Apocrypha is included. The style is quite readable and freeflowing.

No modern translation will ever dominate the field as the King James Version has.

THE LIVING BIBLE (LB, 1971, Tyndale). Although called a paraphrase, this work of Kenneth Taylor is bound and marketed like a translation. Indeed, a strong case can be made that there is no essential distinction between paraphrase and translation, but rather a continuum between more literal and looser translations. The preface says that “its purpose is to say as exactly as possible what the writers of the Scriptures meant, and to say it simply, expanding where necessary for a clear understanding by the modern reader.” This is essentially the goal of any translation, although the KJV, for example, usually italicized what it considered necessary expansions. Many evangelical scholars have felt that too many passages are interpreted too freely or imaginatively. But the phenomenal worldwide success of this volume testifies that its idiomatic use of language has made the Bible lively for multitudes of people.

THE MODERN LANGUAGE BIBLE (MLB, 1959, Zondervan). This was long known as the Berkeley Version for the California residence of the translator of the New Testament, Gerrit Verkuyl. A committee of twenty evangelicals, under Verkuyl’s chairmanship, produced the Old Testament. In general, reviewers have found more to commend this translation than has the buying public. The many explanatory footnotes sometimes become pious observations.

THE NEW AMERICAN BIBLE (NAB, 1970, several publishers). The Catholic Biblical Association of America used the original language instead of the traditional Latin in this translation. (While being prepared it was usually called the “confraternity” version.) The fifty-member team includes a few “separated brothers” and thus “fulfills the directive” of Vatican II. The NAB naturally includes the Apocrypha and appears to be the standard translation for Catholics who prefer not to use translations prepared by Protestants. Don’t confuse it with the NASB.

NEW AMERICAN STANDARD BIBLE (NASB, 1971, several publishers). Sponsored by the Lockman Foundation, this translation aims at adhering as closely as possible to the original language of Scripture, and doing so in a fluent and readable style. It was undertaken in the conviction that the American Standard Version of 1901 “retains its acceptability for pulpit reading and personal memorization.” Nonetheless, the staunchly evangelical translation team found it necessary to depart from the ASV policy of word-for-word literalness. The approach remains conservative, however, following Hebrew and Greek rather than English patterns. Marginal notes and cross-references are a prominent feature.

NEW ENGLISH BIBLE (NEB, 1970, Cambridge, Collins, Oxford). This British translation was intended to be used alongside the King James. It aimed at conveying a “timeless” English, at being accurate yet not pedantic, and at removing “a real barrier between a large proportion of our fellow-countrymen and the truth.” It was prepared under the auspices of all of the large denominations in Great Britain. The translators held that faithfulness does not always demand a word-for-word rendering, and that the chief criterion of translation is intelligibility.

NEW INTERNATIONAL VERSION (NIV, 1978, Zondervan). Work began in earnest on this translation in 1967 when the New York International Bible Society backed the project. “Few translations since the King James,” it is claimed, “have been as carefully done as this one. At each stage of the process there has been a wrestling of various minds with the sacred text and an honest attempt to say in simple, clear English what the Bible writers express in the originals.” The translators were concerned with its literary quality. The NIV team was evangelical, international, and from a wide range of denominations.

REVISED STANDARD VERSION (RSV, 1952, several publishers). A revision of the 1901 American Standard Version, its aim was to “embody the best results of modern scholarship as to the meaning of the Scriptures, and express this meaning in English diction which is designed for use in public and private worship and preserves those qualities which have given to the King James Version a supreme place in English literature.” Although produced under the auspices of most of the larger American Protestant denominations, this translation has won acceptance also in many Catholic and evangelical circles. Many biblical commentaries have used the RSV as their basic text.

Consider a Study Bible

Annotated study editions are available for the NASB, an advantage over the NIV, which right now has no concordance and has relatively few footnotes (which give alternate renderings and sources of Old Testament quotes in the New Testament). By contrast all NASB editions have extensive marginal cross-references to related passages and almost all of them have concordances. The KJV and RSV have long had study editions.

In addition, there are at least three NASB study editions to choose from. The Ryrie Study Bible, newly released by Moody Press, was prepared by Charles Ryrie of Dallas seminary. (The New Testament has been out since 1976 and the same study helps are also available with the KJV.) The Open Bible, with notes from twenty-eight scholars, has been available from Thomas Nelson for three years using the KJV and will soon be available with the NASB also. For two years A. J. Holman has had a “study edition” of the NASB, with helps from fourteen scholars. These helps were transferred mostly from an earlier edition of the RSV.

All three NASB study editions not only have concordances but equally useful topical indexes to the themes of Scripture. They also have several general articles on Bible study, plus introductions and outlines for each book of the Bible. The Open Bible in a few instances and Ryrie also have explanatory and doctrinal footnotes on the same page as the text. There are advantages to this procedure (which is familiar to users of the Scofield Reference Bible with which Ryrie is in doctrinal accord), but there is a drawback if a reader does not sufficiently distinguish between the inspired Word of God and the uninspired comments on it. In general, Ryrie’s notes reflect a scholarly, evangelical consensus. He indicates in places that there are differing interpretations among believers, but on other matters, especially with respect to predictions of future events, Ryrie gives no hint of widespread differences among devout Bible students.