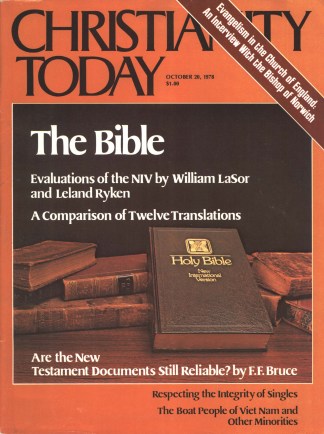

Many Christians seem confused by the availability of so many different translations of the Bible. Older Christians did not face so many choices. They had to learn the language of the King James, and if they could do it, why can’t others? God has indeed marvelously blessed the King James translation over the centuries. But language changes; it does not remain static; and new translations are needed.

CHRISTIANITY TODAY recommends that no version should be the “standard,” neither the King James nor any other translation. You can memorize Scripture from a variety of translations. It’s more important to understand a verse than to know how it is worded in a certain version. Preachers, aware of the variety of translations used by their audiences, can use them together in sermons to expound Scripture. A Bible study group may wish everyone to have a common translation, but why not rotate which translation you use? You can get more out of the Bible when you read different translations of the same passage. (You can also get the same benefit by studying Scripture in a foreign language.)

We must never forget that the principal purpose of words is communication. Jesus Christ who is the incarnate Word of God looked and acted like a man of his time. In the same way, the written Word of God was inspired in the everyday languages of the people who first received it.

Since the Greek of the New Testament differed from the older Greek of the classical Athenian writers, scholars long thought it a special “Holy Ghost” dialect. With the discoveries of ancient documents, we now realize that New Testament Greek differs from the classical because it was the common, somewhat simplified, dialect spread by the conquering Alexander the Great.

We welcome the appearance and increased use of translations that more clearly communicate the meaning of the original Hebrew and Greek to readers today. And there is evidence that understanding of God’s Word is significantly enhanced by modern versions.

For example, the principal of a major Christian school in Maryland carefully tested more than 300 students in grades four through eight in schools in three states. He compared the King James (modified by paragraphing, repunctuations, and modernization of the most blatant archaisms), the New American Standard, and the New International. In every school, at every grade level, and on each of the four kinds of tests, the New International proved to communicate the best, the King James least so, and the New American Standard half-way between. And that despite the regular usage of the King James in home and school by most of the students. Those without such a background could be expected to fare worse.

For example, researchers at Georgia State University compared the readability of the Good News Bible, the Revised Standard, and the King James. The Good News came out notably better than either of the more traditional versions. Indeed, researchers found the RSV and KJV in key respects to resemble the instructions for Federal Income Tax forms.

We understand the written Word of God best when we read and hear it in our own language—in the vernacular of the day. The gap between what we read in the Bible and what we face in secular culture is wide enough without confronting the reader with an unfamiliar vocabulary and archaic grammar.

The presence of many good alternatives to the King James will keep any one of them from becoming dominant. That should ensure that Bible translating will continue. We want to clearly communicate to contemporary men what God revealed to the ancient readers of Hebrew and Greek millenia ago. We need to hear, to understand, and to obey his Word every bit as much now as people did then.

The Root Of All Evil

There is much wistful talk in evangelical circles about the need for revival in the American church, but few offer any serious diagnosis or propose a realistic cure for the church’s lethargy. Many explanations have been advanced but the best one may have been largely ignored by evangelicals—and it’s found in First Timothy 6:10. It says, “Loving money leads to all kinds of evil, and some men in the struggle to be rich have lost their faith and caused themselves untold agonies of mind” (Phillips). Perhaps the reason for the maladies that beset America is that the Christians who live in the richest nation in history have their biblical financial priorities askew.

Before you reject this with a “That’s not me, brother,” consider this warning from Moses: “Take heed … lest, when you have eaten and are full and have built goodly houses and lived in them, and when your herds and flocks multiply, and your silver and gold is multiplied, then your heart be lifted up, and you forget the LORD your God, … and you say in your heart. ‘My power and the might of my hand have gotten me this wealth.’ You shall remember the LORD your God, for it is he who gives you power to get wealth” (Deut. 8:11–14, 17–18).

An antidote to this spiritual poison would, of course, be Christian giving. The Preacher in Ecclesiastes comments that “there is a grievous evil which I have seen under the sun: riches were kept by their owner to his hurt” (Eccles. 5:13). From Abraham and Melchizedek (Gen. 14), to Malachi and the nation of Israel (Mal. 3), to Paul and the collection for Jerusalem (2 Cor. 9), Scripture is clear that God expects all Christians to hold “their” possessions with an open hand, freely offering them to those in need at his direction. Just as day-old manna spoiled, hoarded property loses its power to satisfy our needs.

But giving per se is no remedy for the Deuteronomy 8 disease. Giving must be done with the proper attitude and in the proper manner to please God. Malachi gets right to the heart of the issue when he decries Israel for their unworthy gifts (Mal. 1:7–14). The Israelites sacrificed to the Lord the blind, the lame, and the sick from their flocks and even railed at having to fulfill this duty. In response to this, God says “I have no pleasure in you, and I will not accept an offering from your hand.”

How often do we as Christians give our Lord the left-overs? We live to the limit of our desires and then give the scraps off our table to him. Like the children of Israel, we bring to him that for which we had no use. The Israelites wanted to dispose of the worst of their flocks. This was good animal husbandry, yet the Lord demanded the best, the spotless, the unblemished. Our actions often proclaim that we feel that the Creator and Sustainer of the universe is only worthy of the tattered residue of our lives and possessions.

The New Testament erects a positive standard with respect to material possessions that provides an alternative to the attitudes evident in Malachi 1. Our Lord gave freely from his earthly poverty to meet the needs of others and he expected others to do so, whatever their state. The stories of the widow’s mite (Mark 12:42 ff.) and of Lazarus and Dives (Luke 16:19 ff.) show that the biblical imperative of giving crosses the whole economic spectrum.

First John 3:16–18 sets down the general principles for the Christian use of wealth. The Apostle says, “we ought to lay down our lives for the brethren. But if any one has the world’s goods and sees his brother in need, yet closes his heart against him, how does God’s love abide in Him? Little children, let us not love with word, or with tongue, but in deed and in truth.” Paul tells us not to seek our own advantage, but rather let “every man seek another’s wealth” (1 Cor. 10:24). It is this spirit of servanthood, of sensitivity to the needs of others, that is so dramatically lacking in the American church. Most Christians are so concerned with the accretion of material goods that they have no vision for the needy world around them.

Where is the spirit that Paul exhorted Timothy to exhibit when he wrote, “if we have food and clothing, with these we shall be content” (1 Tim. 6:8)? Quite in opposition to that attitude, evangelical circles are increasingly pervaded by a theology of worldly success. We are told, or at least encouraged to infer, that the godly man will be a material success, that prosperity is concomitant to spirituality. Some evangelical leaders even proclaim that God is glorified by a lavish life style. We are children of the King and should live as befits royalty.

There is no denying that God can and does provide material prosperity, but it is a crucial misunderstanding of Scripture to claim that financial success is part of our guaranteed earthly birthright. Paul warns us to “withdraw from those who suppose that gain is godliness” (1 Tim. 6:5). Moreover, many people assume that the blessing of God on our financial lives must be flaunted ostentatiously to prove that “God always goes first class.” This, too, is a tragic misapprehension of the scriptural injunction: “all of you, clothe yourselves with humility toward one another for God is opposed to the proud, but gives grace to the humble” (1 Pet. 5:5).

God does not demand an other-worldly asceticism of us. Paul denigrates this as mere “will-worship” (Col. 2:23) and affirms the fact that God “richly furnishes everything to enjoy” (1 Tim. 6:17). America’s prosperity can be a great source of pleasure to Christians, but we must not seek that enjoyment as an end in itself. Rather, we ought to receive it as an incidental by-product of following God (Matt. 6:33). Paul concludes his instruction to Timothy concerning proper financial priorities by saying, “As for the rich in this world, charge them not to be haughty, nor to set their hopes on uncertain riches, but on God.… They are to do good, to be rich in good deeds, liberal and generous, thus laying up for themselves a good foundation for the future, so that they may take hold of the life which is life indeed” (1 Tim. 6:17–19).

The denial of this standard by the church could well be the source of its present impotence and ennui, for Christ said, “If you are not fit to be trusted to deal with the material wealth of this world, who will trust you with the true riches” (Luke 16:11, Phillips)? Revival in our midst and renewal of our crumbling society can come only as we individually and corporately eschew the love of money in favor of more lasting and truly profitable values.—DOUGLAS H. KIESEWETTER, JR., Christian Stewardship Assistance, Dallas, Texas.

Cosmomorphism

About twenty years ago Elton Trueblood suggested in his Philosophy of Religion that we should construct a big word, composed of several Greek derivatives, to counter the word anthropomorphism. Pantheists, believers in an impersonal God, have used that word to frighten people who believe in a personal God.

I have finally come up with such a word—cosmomorphism. It roughly translates “having the form of the world,” just as anthropomorphism means “having the form of man”—and both of them are dangerous.

The Scripture warns that, even though man is made in the image of God, we must be cautious in our comparisons. “God is not man, that he should lie, or a son of man, that he should repent” (Num. 23:19). “For my thoughts are not your thoughts, neither are your ways my ways, says the LORD” (Isa. 55:8).

The Bible also warns against comparing God with nature. When God prohibited idolatry he said, “You shall not make yourself a graven image, or any likeness of anything that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth” (Exod. 20:4). In short, you can’t capture the essence of God completely by either human or natural comparisons.

But now that I’ve coined cosmomorphism I’m beginning to think that it may be worse than anthropomorphism. Here’s why: The Scripture says that God made only one creature in his image—man. That means that God is more like man than he is a rock or a tiger. Further, if God revealed himself uniquely in the person of Jesus that makes pantheism look pretty weak when it says that God is just an impersonal being. Why did it require a person to fully reveal God?

As C. S. Lewis has so aptly observed maybe God’s difference from man isn’t the way white differs from black, but more similar to the way that a perfect circle differs from a child’s first attempt to draw one. Anthropomorphism, then, isn’t quite as dangerous as we’ve been told and cosmomorphism may mislead more than it would help.

Could this mean that the biblical literalist is closer to the truth than the sophisticated demythologizer?

Can John Doe be smarter than Rudolph Bultmann?

What a thought.—ARLIE J. HOOVER, dean, Columbia Christian College, Portland. Oregon.