The CHRISTIANITY TODAY—Gallup Poll shows the Bible is highly revered but seldom used.

If future church historians choose to describe the last half of this century as a “crisis,” they might well choose to say there was a crisis of authority. Such a crisis exists both inside and outside the church. It may be seen outside in the collapse of society, the resort to violence, the selfish disregard of others, and the desire for instant gratification. Inside the church it appears in such matters as changing attitudes toward sex, redefinitions of worldliness, and the increasing success of the cults, but particularly in attitudes toward the Bible.

To discover the prevailing view of the Bible in the general public and specifically among Protestants and Catholics, the CHRISTIANITY TODAY-Gallup Poll asked questions in four areas. First, where do Americans stand with respect to religious authority. Second, how do they view the reliability of the Bible? Third, how often do they read the Bible, and how much do they know of it? Fourth, what effect does Bible reading have on their beliefs and lives? The answers were then given to a group of America’s leading experts on religious life for evaluation.

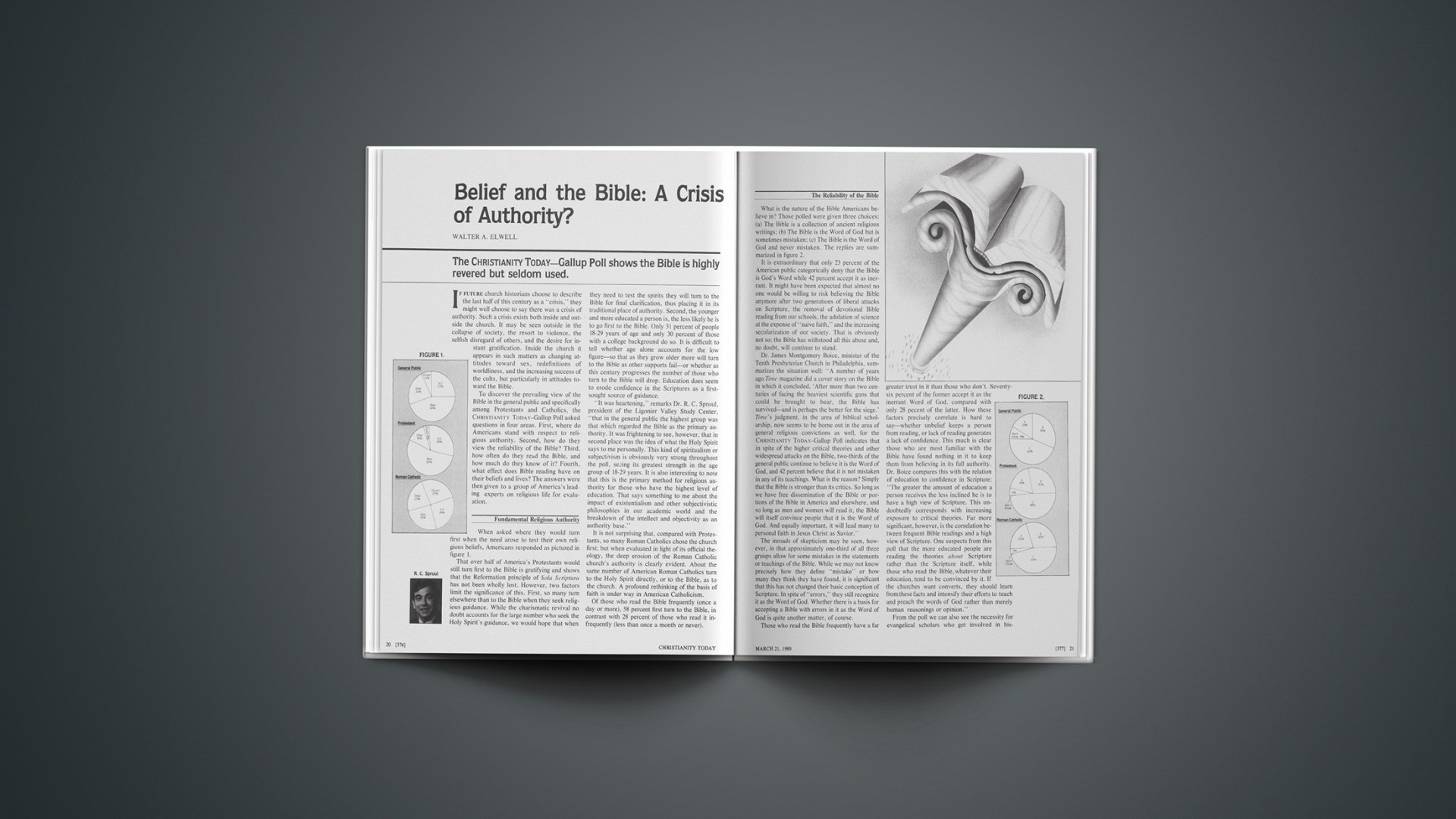

Fundamental Religious Authority

When asked where they would turn first when the need arose to test their own religious beliefs, Americans responded as pictured in figure 1.

That over half of America’s Protestants would still turn first to the Bible is gratifying and shows that the Reformation principle of Sola Scriptura has not been wholly lost. However, two factors limit the significance of this. First, so many turn elsewhere than to the Bible when they seek religious guidance. While the charismatic revival no doubt accounts for the large number who seek the Holy Spirit’s guidance, we would hope that when they need to test the spirits they will turn to the Bible for final clarification, thus placing it in its traditional place of authority. Second, the younger and more educated a person is, the less likely he is to go first to the Bible. Only 31 percent of people 18–29 years of age and only 30 percent of those with a college background do so. It is difficult to tell whether age alone accounts for the low figure—so that as they grow older more will turn to the Bible as other supports fail—or whether as this century progresses the number of those who turn to the Bible will drop. Education does seem to erode confidence in the Scriptures as a first-sought source of guidance.

“It was heartening,” remarks Dr. R. C. Sproul, president of the Ligonier Valley Study Center, “that in the general public the highest group was that which regarded the Bible as the primary authority. It was frightening to see, however, that in second place was the idea of what the Holy Spirit says to me personally. This kind of spiritualism or subjectivism is obviously very strong throughout the poll, seeing its greatest strength in the age group of 18–29 years. It is also interesting to note that this is the primary method for religious authority for those who have the highest level of education. That says something to me about the impact of existentialism and other subjectivistic philosophies in our academic world and the breakdown of the intellect and objectivity as an authority base.”

It is not surprising that, compared with Protestants, so many Roman Catholics chose the church first; but when evaluated in light of its official theology, the deep erosion of the Roman Catholic church’s authority is clearly evident. About the same number of American Roman Catholics turn to the Holy Spirit directly, or to the Bible, as to the church. A profound rethinking of the basis of faith is under way in American Catholicism.

Of those who read the Bible frequently (once a day or more), 58 percent first turn to the Bible, in contrast with 28 percent of those who read it infrequently (less than once a month or never).

The Reliability of the Bible

What is the nature of the Bible Americans believe in? Those polled were given three choices: (a) The Bible is a collection of ancient religious writings; (b) The Bible is the Word of God but is sometimes mistaken; (c) The Bible is the Word of God and never mistaken. The replies are summarized in figure 2.

It is extraordinary that only 23 percent of the American public categorically deny that the Bible is God’s Word while 42 percent accept it as inerrant. It might have been expected that almost no one would be willing to risk believing the Bible anymore after two generations of liberal attacks on Scripture, the removal of devotional Bible reading from our schools, the adulation of science at the expense of “naive faith,” and the increasing secularization of our society. That is obviously not so; the Bible has withstood all this abuse and, no doubt, will continue to stand.

Dr. James Montgomery Boice, minister of the Tenth Presbyterian Church in Philadelphia, summarizes the situation well: “A number of years ago Time magazine did a cover story on the Bible in which it concluded, ‘After more than two centuries of facing the heaviest scientific guns that could be brought to bear, the Bible has survived—and is perhaps the better for the siege.’ Time’s judgment, in the area of biblical scholarship, now seems to be borne out in the area of general religious convictions as well, for the CHRISTIANITY TODAY-Gallup Poll indicates that in spite of the higher critical theories and other widespread attacks on the Bible, two-thirds of the general public continue to believe it is the Word of God, and 42 percent believe that it is not mistaken in any of its teachings. What is the reason? Simply that the Bible is stronger than its critics. So long as we have free dissemination of the Bible or portions of the Bible in America and elsewhere, and so long as men and women will read it, the Bible will itself convince people that it is the Word of God. And equally important, it will lead many to personal faith in Jesus Christ as Savior.”

The inroads of skepticism may be seen, however, in that approximately one-third of all three groups allow for some mistakes in the statements or teachings of the Bible. While we may not know precisely how they define “mistake” or how many they think they have found, it is significant that this has not changed their basic conception of Scripture. In spite of “errors,” they still recognize it as the Word of God. Whether there is a basis for accepting a Bible with errors in it as the Word of God is quite another matter, of course.

Those who read the Bible frequently have a far greater trust in it than those who don’t. Seventy-six percent of the former accept it as the inerrant Word of God, compared with only 28 pecent of the latter. How these factors precisely correlate is hard to say—whether unbelief keeps a person from reading, or lack of reading generates a lack of confidence. This much is clear those who are most familiar with the Bible have found nothing in it to keep them from believing in its full authority. Dr. Boice compares this with the relation of education to confidence in Scripture: “The greater the amount of education a person receives the less inclined he is to have a high view of Scripture. This undoubtedly corresponds with increasing exposure to critical theories. Far more significant, however, is the correlation between frequent Bible readings and a high view of Scripture. One suspects from this poll that the more educated people are reading the theories about Scripture rather than the Scripture itself, while those who read the Bible, whatever their education, tend to be convinced by it. If the churches want converts, they should learn from these facts and intensify their efforts to teach and preach the words of God rather than merely human reasonings or opinion.”

From the poll we can also see the necessity for evangelical scholars who get involved in historical criticism of the Bible and matters of biblical introduction. They must set forth clearly and convincingly views consistent with evangelical faith.

Bible Reading and Bible Knowledge

We are encouraged to learn that America’s beliefs about the Bible have managed to stay significantly on track in spite of all the attempts to discredit it. But we are discouraged to see how few actually turn to the Bible (as opposed to what they hypothetically would do “if” they wanted a question answered), and how little they know of it. It is apparently one thing to believe that the Bible is God’s Word and quite another to read it.

These facts reflect dismally upon the reading habits of the American people. We have to reject the explanation that people are not reading much these days. Retail book selling has been growing year by year for the last 25 years. A standard reference work lists over 8,000 publishers in America, an increase of 40 percent over five years ago. It is not that we aren’t reading very much; it is rather that we are not reading the Bible very much.

We are also troubled that both those who are younger and those who are more educated tend not to read the Bible very frequently. Only 14 percent of those with a college background and 6 percent of the 18-to 29-year-olds reported reading the Bible daily or more. It is also troubling that 56 percent of the college-educated and 58 percent of the 18-to 29-year-olds read it less than once a month or never.

FIGURE 3.

The same unhappy situation exists in the area of factual Bible knowledge. When people fail to read the Bible it is unlikely they will know much about it. CHRISTIANITY TODAY chose one of the best-known chapters in the New Testament (John 3) and one of its most frequently heard references (“ye must be born again”) to test the public’s biblical literacy. Responses to the question “Which of the statements is what the Bible says Jesus told Nicodemus?” are indicated in figure 4 (the choices were supplied by the questionnaire).

When asked how many of the Ten Commandments they could name, 45 percent of the general public could name only tour or fewer, as compared with 49 percent of the Protestants, and 44 percent of the Roman Catholics.

When asked how many of the Ten Commandments they could name, 45 percent of the general public could name only four or fewer, as compared with 49 percent of the Protestants, and 44 percent of the Roman Catholics.

These two tests reveal the dismally low state of American biblical knowledge. Over 40 percent of any group did not know what Jesus said to Nicodemus, even when supplied with the answer, and could not name even five of the Ten Commandments. It is no surprise that the cults and aggressive people who claim religious authority, sometimes even biblical authority, are making such gains today. It would appear that most people simply would not know the difference between theological truth and error. When a person does not know even the simplest biblical facts, is he likely to understand more complex doctrines? It is similar to the situation of a man whose car wouldn’t start during a sub-zero period. When someone suggested that the trouble might be with the carburetor, he replied, “What’s a carburetor?” Little wonder he couldn’t solve the problem! Little wonder our churches are often weak and easy prey for religious hucksters.

Dr. Colin Brown, professor of systematic theology at Fuller Theological Seminary, aptly observes: “These facts about Bible reading and knowledge suggest that all the churches have a long way to go in Christian education and building up their members in regular Bible study. Comparison of the 72 percent who believe the Bible to be the Word of God in one fashion or other with the 12 percent who read it once or more daily suggests that the Bible is venerated as a sacred object. But in practice it is evidently not considered at all profitable for teaching, for reproof, and for training in righteousness.”

FIGURE 4.

That so few people know the Ten Commandments was particularly distressing to Dr. R. C. Sproul, because it indicates “a dismal ignorance of the ethical content of Scripture. We seem to be at a low ebb in the educating of our people into the Christian faith as a value system and an ethical system.”

Effects on Actions and Theology

Christianity Today probed beyond simply what people believed, because it is also necessary to examine what effect those beliefs and the relative frequency of bible reading have on their lives. What emerged was that a cluster of activities—reading the Bible frequently, attending church, talking about one’s faith, contributing financially to the church, and doing volunteer religious work—all corresponded rather closely, indicating that no one activity alone could fully account for a person’s action or belief; more likely, some combination of them did.

While we are mindful of this, we have singled out frequency of Bible reading for discussion, defining “frequent reading” as once a day or more and “infrequent reading” as less than once a month, or never.

Belief in God is not much affected by how often people read the Bible. While all believe in God who read it frequently, so do 92 percent of those who read it only infrequently. However, the first group have a clearer perception of who God is and draw much more consolation from knowing God. Of those who read the Bible frequently, 92 percent say they derive “a lot” of consolation from their beliefs about God, but only 40 percent of infrequent readers testify to such consolation. No doubt this is because those who read their Bible frequently have a more accurate understanding of God than those who do not; when they need consolation, they turn to the Bible for help and find it.

Dr. Millard Erickson, professor of theology at Bethel Theological Seminary, observes that it is no surprise that those who “have had a conversion, read their Bible frequently, attend church frequently, talk often about their faith, and tithe, derive a great deal of consolation and help from their beliefs. Christianity works for those who practice it.”

There is a striking contrast between those who say they have had a religious experience and those who haven’t when it comes to reading the Bible: 74 percent of the former read the Bible frequently, and 79 percent of the latter read the Bible infrequently. Obviously, a personal experience with God fills a person with a love for Scripture, whereas little desire for it exists where such experience is absent. Ninety-eight percent of frequent readers said their experience involved Jesus Christ, whereas only 64 percent of infrequent readers said this. Bible reading clearly gave specific Christian definition to such experience.

Both frequent and infrequent Bible readers were asked, “Are you a Pentecostal or charismatic Christian?” Figure 5 records the results.

That twice as many frequent readers of the Bible are noncharismatic as charismatic seems to indicate that people immersed in Scripture feel less need for ecstatic immediacy. The reading of Scripture provides a sense of security and nearness of God that is sufficient to meet their spiritual needs.

Conclusion

Where does all this leave us? Obviously, the results are a mixed bag. R. C. Sproul draws this conclusion: “The bottom line is that we have a populace who, for the most part, are uneducated about the content of the Scriptures, and particularly with respect to the ethical mandates of Scripture. There is a broad nebulous understanding of certain principles of right and wrong, and certain concepts of God, but the real information and content of Scripture is at a low ebb, and I think that, more than anything else, is reflected in the failure of the church to make an impact on secular culture. In spite of this, we have extremely high numbers of professed conversion experiences. The impact is not being made because of a significant lack of follow-up in which our understanding is affected by the Word of God.”

He continues, “In other words, we are having a revival of feeling but not of knowledge of God. The church’s most serious problem is that people both outside and inside the church do not really know who God is and what he requires of us.”

Colin Brown raises these final points for discussion: “Is the church today more guided by feelings than by convictions? Do we value enthusiasm more than informed commitment? Is there a credibility gap between veneration of the Bible and knowledge of its contents? It would seem so from the figures represented in the poll.”

FIGURE 5.

We can draw certain conclusions about the ministry of the church. First, Americans are strongly committed to the Bible as their religious authority, but have a great need to clarify what that means. Second, subjectivism is creeping into our religious life so that we need a resounding reaffirmation of the Bible’s objective authority. Third, there is pitiful ignorance of the content of Scripture, so the churches must gear their educational programs to the task of teaching their people. Fourth, the importance of reading the Bible is evident, so the churches must increase their efforts to get people to spend time with it. Fifth, we must find ways to help people turn their religious beliefs into actions. The world needs to see faith in action.

Carl F. H. Henry, first editor of Christianity Today, is lecturer at large for World Vision International. An author of many books, he lives in Arlington, Virginia.