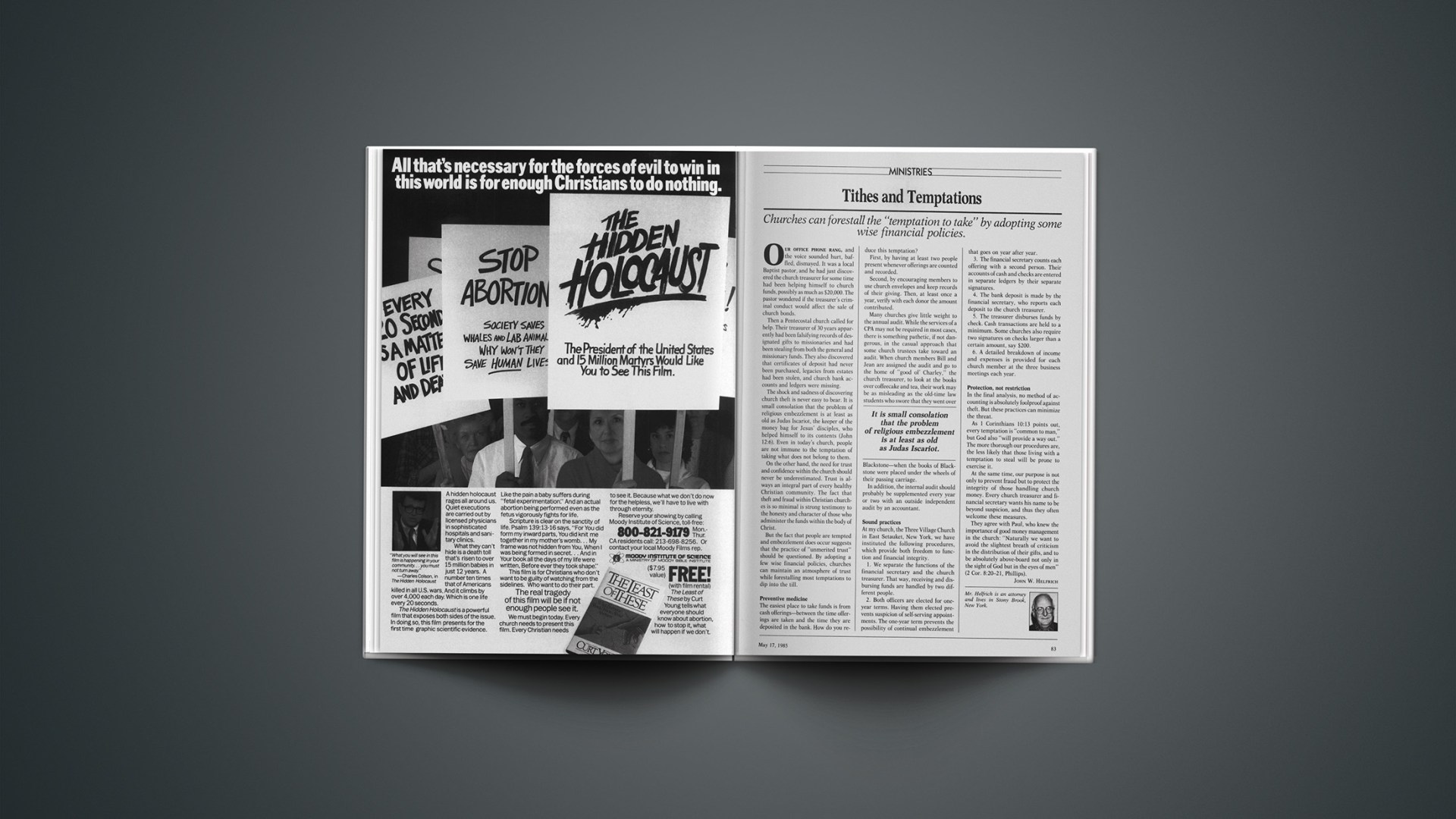

Churches can forestall the “temptation to take” by adopting some wise financial policies.

Our office phone rang, and the voice sounded hurt, baffled, dismayed. It was a local Baptist pastor, and he had just discovered the church treasurer for some time had been helping himself to church funds, possibly as much as $20,000. The pastor wondered if the treasurer’s criminal conduct would affect the sale of church bonds.

Then a Pentecostal church called for help. Their treasurer of 30 years apparently had been falsifying records of designated gifts to missionaries and had been stealing from both the general and missionary funds. They also discovered that certificates of deposit had never been purchased, legacies from estates had been stolen, and church bank accounts and ledgers were missing.

The shock and sadness of discovering church theft is never easy to bear. It is small consolation that the problem of religious embezzlement is at least as old as Judas Iscariot, the keeper of the money bag for Jesus’ disciples, who helped himself to its contents (John 12:6). Even in today’s church, people are not immune to the temptation of taking what does not belong to them.

On the other hand, the need for trust and confidence within the church should never be underestimated. Trust is always an integral part of every healthy Christian community. The fact that theft and fraud within Christian churches is so minimal is strong testimony to the honesty and character of those who administer the funds within the body of Christ.

But the fact that people are tempted and embezzlement does occur suggests that the practice of “unmerited trust” should be questioned. By adopting a few wise financial policies, churches can maintain an atmosphere of trust while forestalling most temptations to dip into the till.

Preventive Medicine

The easiest place to take funds is from cash offerings—between the time offerings are taken and the time they are deposited in the bank. How do you reduce this temptation?

First, by having at least two people present whenever offerings are counted and recorded.

Second, by encouraging members to use church envelopes and keep records of their giving. Then, at least once a year, verify with each donor the amount contributed.

Many churches give little weight to the annual audit. While the services of a CPA may not be required in most cases, there is something pathetic, if not dangerous, in the casual approach that some church trustees take toward an audit. When church members Bill and Jean are assigned the audit and go to the home of “good ol’ Charley,” the church treasurer, to look at the books over coffeecake and tea, their work may be as misleading as the old-time law students who swore that they went over Blackstone—when the books of Blackstone were placed under the wheels of their passing carriage.

In addition, the internal audit should probably be supplemented every year or two with an outside independent audit by an accountant.

Sound Practices

At my church, the Three Village Church in East Setauket, New York, we have instituted the following procedures, which provide both freedom to function and financial integrity.

1. We separate the functions of the financial secretary and the church treasurer. That way, receiving and disbursing funds are handled by two different people.

2. Both officers are elected for one-year terms. Having them elected prevents suspicion of self-serving appointments. The one-year term prevents the possibility of continual embezzlement that goes on year after year.

3. The financial secretary counts each offering with a second person. Their accounts of cash and checks are entered in separate ledgers by their separate signatures.

4. The bank deposit is made by the financial secretary, who reports each deposit to the church treasurer.

5. The treasurer disburses funds by check. Cash transactions are held to a minimum. Some churches also require two signatures on checks larger than a certain amount, say $200.

6. A detailed breakdown of income and expenses is provided for each church member at the three business meetings each year.

Protection, Not Restriction

In the final analysis, no method of accounting is absolutely foolproof against theft. But these practices can minimize the threat.

As 1 Corinthians 10:13 points out, every temptation is “common to man,” but God also “will provide a way out.” The more thorough our procedures are, the less likely that those living with a temptation to steal will be prone to exercise it.

At the same time, our purpose is not only to prevent fraud but to protect the integrity of those handling church money. Every church treasurer and financial secretary wants his name to be beyond suspicion, and thus they often welcome these measures.

They agree with Paul, who knew the importance of good money management in the church: “Naturally we want to avoid the slightest breath of criticism in the distribution of their gifts, and to be absolutely above-board not only in the sight of God but in the eyes of men” (2 Cor. 8:20–21, Phillips).

Mr. Helfrich is an attorney and lives in Stony Brook, New York.