Outside mainstream evangelicalism and fundamentalism, the Bible-college movement is little known. And even in these circles, it is often little understood. Bible colleges tend to suffer from an image problem. Many perceive them as extended Bible conferences—or, at best, “junior” Christian liberal-arts colleges. Neither is true.

Bible colleges are similar to seminaries in that they are professional schools whose primary purpose is to train students for vocations in Christian ministry. This focus of purpose influences all aspects of these institutions. Training is provided for a number of roles, including the pastorate, Christian education, youth work, music, missions, and other church-related vocations. Christian liberal-arts colleges have a valuable role to play, but it is a much less-focused one than for Bible colleges.

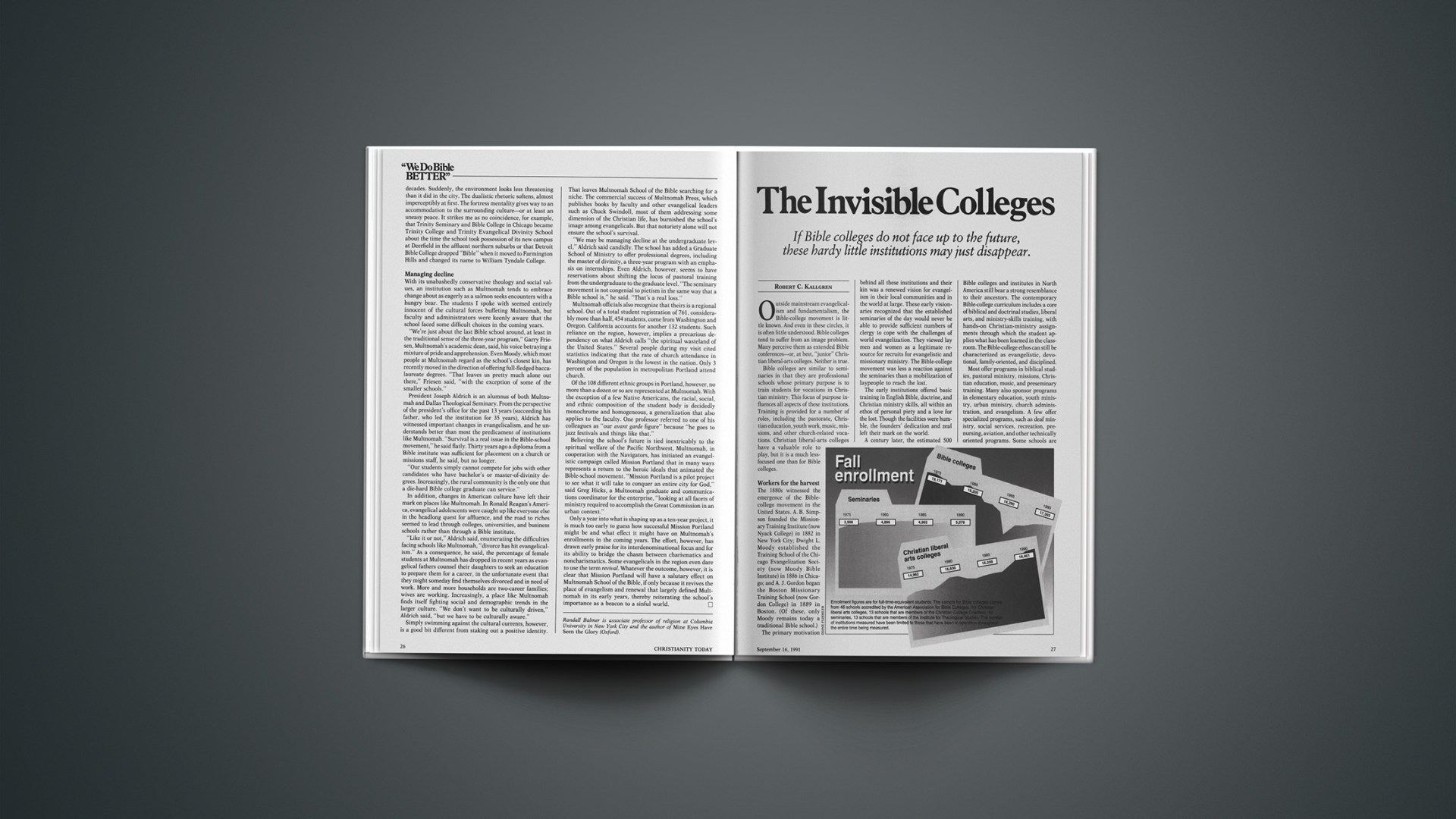

Workers For The Harvest

The 1880s witnessed the emergence of the Bible-college movement in the United States. A. B. Simpson founded the Missionary Training Institute (now Nyack College) in 1882 in New York City; Dwight L. Moody established the Training School of the Chicago Evangelization Society (now Moody Bible Institute) in 1886 in Chicago; and A. J. Gordon began the Boston Missionary Training School (now Gordon College) in 1889 in Boston. (Of these, only Moody remains today a traditional Bible school.)

The primary motivation behind all these institutions and their kin was a renewed vision for evangelism in their local communities and in the world at large. These early visionaries recognized that the established seminaries of the day would never be able to provide sufficient numbers of clergy to cope with the challenges of world evangelization. They viewed lay men and women as a legitimate resource for recruits for evangelistic and missionary ministry. The Bible-college movement was less a reaction against the seminaries than a mobilization of laypeople to reach the lost.

The early institutions offered basic training in English Bible, doctrine, and Christian ministry skills, all within an ethos of personal piety and a love for the lost. Though the facilities were humble, the founders’ dedication and zeal left their mark on the world.

A century later, the estimated 500 Bible colleges and institutes in North America still bear a strong resemblance to their ancestors. The contemporary Bible-college curriculum includes a core of biblical and doctrinal studies, liberal arts, and ministry-skills training, with hands-on Christian-ministry assignments through which the student applies what has been learned in the classroom. The Bible-college ethos can still be characterized as evangelistic, devotional, family-oriented, and disciplined.

Most offer programs in biblical studies, pastoral ministry, missions, Christian education, music, and preseminary training. Many also sponsor programs in elementary education, youth ministry, urban ministry, church administration, and evangelism. A few offer specialized programs, such as deaf ministry, social services, recreation, pre-nursing, aviation, and other technically oriented programs. Some schools are strictly undergraduate institutions, while others offer seminary or graduate programs, or even operate publishing houses, radio stations, and other enterprises.

Bible colleges are distributed throughout North America, with stronger concentrations in the Southeast and Midwest. They are located in urban, suburban, and rural settings, with campuses that range from basic to beautiful. Twenty percent are nondenominational, and the balance represent various denominations, particularly the Church of Christ/Christian Church, Baptist fellowships, Wesleyan groups, and the Assemblies of God. Enrollments range from 50 to 1,500, with a mean of 300. Annual tuition and fees average $3,500 (less than half the average tuition and fees for independent liberal-arts colleges).

Bible-college student bodies tend to be more male, Caucasian, and have a much larger portion of older and married students than most colleges. Bible-college students demonstrate an unusual service orientation. Through Christian-ministry assignments and personal initiative, many hospitals, retirement homes, prisons, and rehabilitation centers have been brightened by these students’ ministry.

One illustration: After Hurricane Hugo smashed through South Carolina in September 1989, the Columbia Bible College student body voluntarily formed itself into dozens of independent teams and, with the guidance of the governor’s office, fanned out across the state to help citizens clean up the devastation.

An Ambiguous Future

Bible colleges rarely travel the “easy street.” With the exception of the period following World War II and the baby-boom market of the sixties and early seventies, recruiting students has been a challenge. My doctoral study, which included 42 Bible colleges, indicates significant current pressure in both student enrollment and institutional finances. This sample of established, mature Bible colleges experienced an aggregate 15 percent decline in enrollment between 1979 and 1986 (though this has turned around somewhat in the last few years). In contrast, a sample of Christian liberal arts colleges (the members of the Christian College Consortium) experienced an aggregate enrollment increase of 16 percent during this same period.

The study also indicated that, according to American Association of Bible Colleges standards, half of the institutions suffer financial stress.

So what of the future of the Bible-college movement? A survey involving 42 Bible-college presidents reveals some ambivalence. While they are convinced that Bible colleges should not become “Christian liberal arts colleges,” they “anticipate decreasing enrollments” and “increased competition from local churches and other providers of biblical/theological instruction.” (Indeed, among some larger churches there is a trend toward establishing programs for ministry training within the confines of the local congregation.) These presidents view the declining commitment to biblical priorities among evangelicals and the changing moral values in North America as contributing to the problem.

Surveys of the traditional employers of Bible-college graduates also provide insight for the future. Mission agencies look to Bible colleges as a significant source of recruits for such traditional hands-on ministries as evangelism, discipleship, church planting, and urban ministry. Survey responses from the chief executives of 113 agencies indicate that while Bible colleges will continue to be a major source of missionary recruits, graduate or seminary credentials are growing in importance.

A survey responded to by the administrators of 151 Christian day schools indicates significant opportunities for Bible-college graduates in Christian-school ministry. These administrators express a strong preference for teachers who are committed to a biblical world view. They are cool toward prospective teachers who are Christians but essentially secular in their education and outlook. They do, however, prefer that Bible-college programs be professionally approved or state certified.

Today the minimal credential for entering many vocations is the college degree, rather than the high-school diploma. Likewise, fewer pulpits are open to the inexperienced, aspiring Bible-college graduate. A seminary degree is becoming the credential of choice. This development will require the Bible-college movement to assess its market with a view toward finding those educational niches that they are uniquely qualified to serve. For many, the process will be difficult and painful. To fit those niches may involve a great deal of change.

Bible colleges are accurately characterized as being conservative institutions. The concept of a liberal Bible college is an oxymoron. This conservatism is essential as it pertains to doctrine, the treatment of the Word of God, and personal ethics and behavior. In some ways, however, this conservative stance also sometimes serves to hinder necessary changes in traditions of an extra-biblical nature.

The Bible-college movement needs to expand its constituency among minorities. The very nature of a Bible college should make it attractive and beneficial to minorities, especially African-Americans and Hispanics. While some Bible colleges have specific ethnic constituencies, all Bible colleges need to provide for ethnic and cultural diversity. Bible colleges will achieve progress in this area only by persistent hard work and sacrifice.

The Bible-college movement has provided trained workers for Christian service for more than a century. Its graduates are a major force in world evangelization. Facing a period of contraction, these institutions must re-evaluate and reassert themselves, perhaps in a modified role, in the future of theological education. The spiritual needs of the world are greater now in depth and scope than they were a century ago. The issue is not whether there is need for training God’s people for service, but rather, how will that enormous need be met? Bible colleges, along with evangelical seminaries, have the primary responsibility for this critical ministry of the church.

Eugene H. Peterson is pastor of Christ Our King Presbyterian Church, Bel Air, Maryland, and author of A Long Obedience in the Same Direction (InterVarsity) and Answering God (Harper & Row), both of which are about the Psalms.