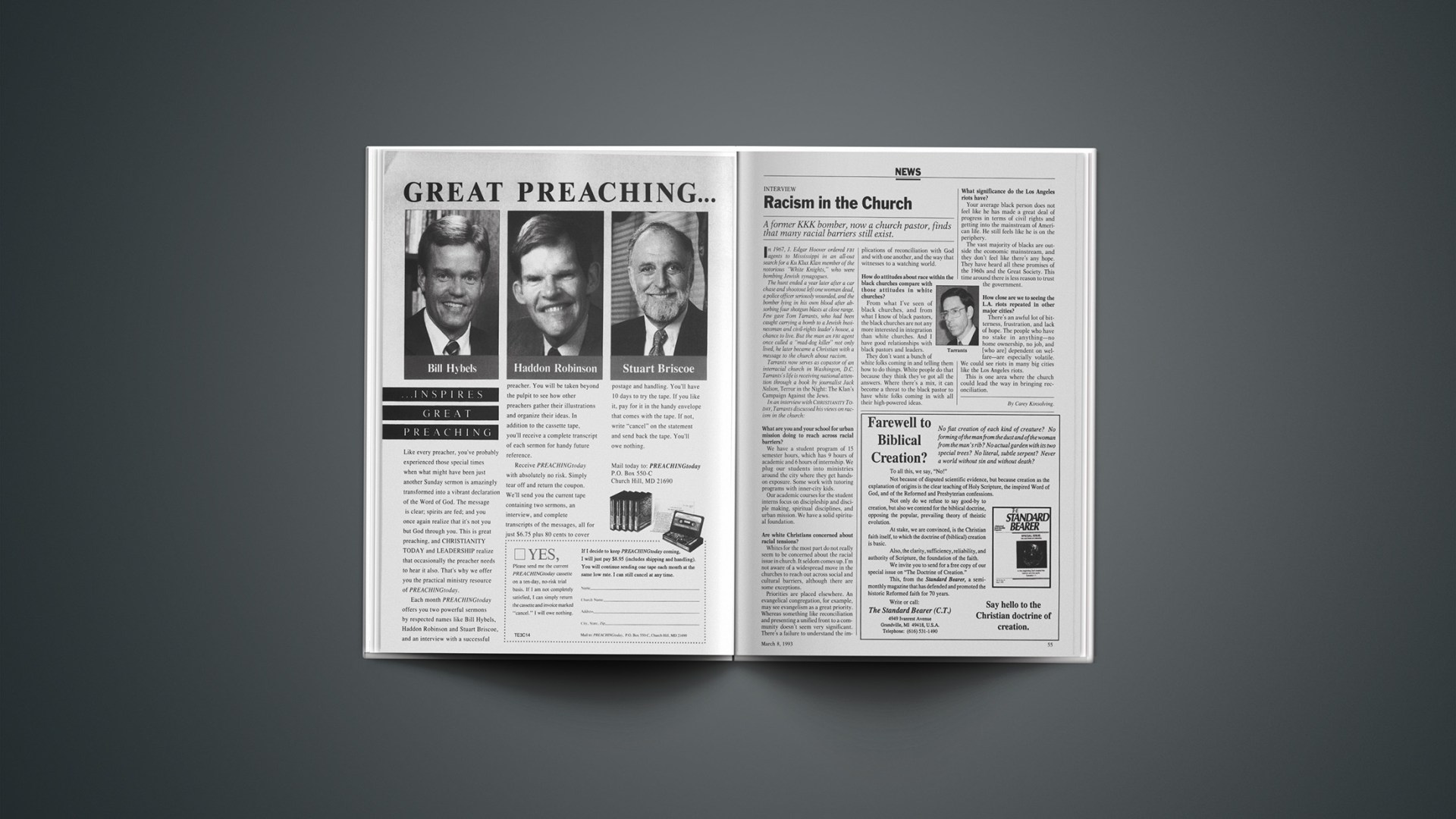

A former KKK bomber, now a church pastor, finds that many racial barriers still exist.

In 1967, J. Edgar Hoover ordered FBI agents to Mississippi in an all-out search for a Ku Klux Klan member of the notorious “White Knights,” who were bombing Jewish synagogues.

The hunt ended a year later after a car chase and shootout left one woman dead, a police officer seriously wounded, and the bomber lying in his own blood after absorbing four shotgun blasts at close range. Few gave Tom Tarrants, who had been caught carrying a bomb to a Jewish businessman and civil-rights leader’s house, a chance to live. But the man an FBI agent once called a “mad-dog killer” not only lived, he later became a Christian with a message to the church about racism.

Tarrants now serves as copastor of an interracial church in Washingon, D.C. Tarrants’s life is receiving national attention through a book by journalist Jack Nelson, Terror in the Night: The Klan’s Campaign Against the Jews.

In an interview with CHRISTIANITY TODAY, Tarrants discussed his views on racism in the church:

What are you and your school for urban mission doing to reach across racial barriers?

We have a student program of 15 semester hours, which has 9 hours of academic and 6 hours of internship. We plug our students into ministries around the city where they get hands-on exposure. Some work with tutoring programs with inner-city kids.

Our academic courses for the student interns focus on discipleship and disciple making, spiritual disciplines, and urban mission. We have a solid spiritual foundation.

Are white Christians concerned about racial tensions?

Whites for the most part do not really seem to be concerned about the racial issue in church. It seldom comes up. I’m not aware of a widespread move in the churches to reach out across social and cultural barriers, although there are some exceptions.

Priorities are placed elsewhere. An evangelical congregation, for example, may see evangelism as a great priority. Whereas something like reconciliation and presenting a unified front to a community doesn’t seem very significant. There’s a failure to understand the implications of reconciliation with God and with one another, and the way that witnesses to a watching world.

How do attitudes about race within the black churches compare with those attitudes in white churches?

From what I’ve seen of black churches, and from what I know of black pastors, the black churches are not any more interested in integration than white churches. And I have good relationships with black pastors and leaders.

They don’t want a bunch of white folks coming in and telling them how to do things. White people do that because they think they’ve got all the answers. Where there’s a mix, it can become a threat to the black pastor to have white folks coming in with all their high-powered ideas.

What significance do the Los Angeles riots have?

Your average black person does not feel like he has made a great deal of progress in terms of civil rights and getting into the mainstream of American life. He still feels like he is on the periphery.

The vast majority of blacks are outside the economic mainstream, and they don’t feel like there’s any hope. They have heard all these promises of the 1960s and the Great Society. This time around there is less reason to trust the government.

How close are we to seeing the L.A. riots repeated in other major cities?

There’s an awful lot of bitterness, frustration, and lack of hope. The people who have no stake in anything—no home ownership, no job, and [who are] dependent on welfare—are especially volatile. We could see riots in many big cities like the Los Angeles riots.

This is one area where the church could lead the way in bringing reconciliation.

By Carey Kinsolving.