Violence, political compromise, and Clinton’s policies trigger a split among abortion opponents over goals and strategy.

More than two decades after Roe v. Wade became the law of the land, the pro-life movement is itself grappling with viability. The movement has divided into three streams, each trying to cut a different channel, but none of them about to become a rushing torrent.

“It has become commonplace to say that the prolife movement is at a crossroads,” says C. Everett Koop, former U.S. surgeon general. “It is more serious than that. The prolife movement took a wrong turn or two. We must start down the right road all over again.”

Pro-lifers can perhaps be described as falling into three broad categories: hardliners, negotiators, and alternative-service providers.

The hardliners, including many in the rescue movement, have carved out the clearest policy position—that abortion is unequivocally wrong—but there is disagreement over the role of violence. A small but growing number of extreme hardliners have condoned—even advocated—shooting abortionists as “justifiable homicide.”

The negotiators have had some successes by making political deals, but they allow for abortion in exceptional cases, a view that hardliners consider expedient and logically questionable. Critics charge they risk losing the fight by compromising too much.

Alternative-service providers, for the most part, agree with hardliners on abortion, but they prefer to focus on crisis pregnancy and adoption services—keeping babies alive on a practical level. They have little political clout and are tiny in comparison to well-funded abortion-rights groups.

The election of Bill Clinton a year ago has galvanized pro-lifers. Yet, the existence of a recognizable foe has not translated into a unified front. Some pro-lifers have been rethinking their positions, while others have moved from one camp to another. Meanwhile, the majority of pro-life leaders are working feverishly to forestall restrictive new legislation. (See “Menacing FACE-Off for Pro-lifers,” p. 42.)

What Price unity?

The strife within the movement is best symbolized by Texans United for Life president Bill Price, who criticized Operation Rescue National (ORN) for its Dallas Cities of Refuge campaign in July. He believes the rescue movement has become fanatical in stalking children of abortionists, vandalizing clinics, and interrupting worship services attended by abortionists.

“Any organization or movement that shows disdain for the law will attract individuals who actually want and enjoy lawlessness,” says Price. “If the pro-life movement does not police itself, the government will.”

ORN executive director Keith Tucci of Melbourne, Florida, counters, “We have had 72,000 arrests and not once has anyone been convicted of hurting anybody or damaging property. We always make people sign a pledge of nonviolence in word and deed.” Tucci says the Cities of Refuge campaign in seven locations was ORN’s most successful campaign because three-fourths of the 10,000 involved were first-time participants.

“There is a place for Operation Rescue on the bus,” Price says. “But if they are allowed behind the wheel, the movement will end up in a ditch.”

Operation Rescue founder Randall Terry, now president of the Christian Defense Coalition in Washington, D.C., says, “Bill [Price] is a misguided man, and frankly a great asset to the abortion industry. The most tragic thing is the content of what he is saying: ‘Don’t rescue; let the babies die.’ Anyone who opposes Operation Rescue is clearly betraying the supremacy of God’s law.”

Rutherford Institute founder John Whitehead notes that the annual number of abortions in America—1.6 million—has not dropped because of the rescue movement. “The goals of some of the leadership of the pro-life movement have become, or at least appear to be, somewhat distracted from the goal of ending abortion,” Whitehead says in his new booklet, A Pro-Life Manifesto.

Concession stand

Koop, who is touring the country this fall to promote Clinton’s health-care reform plan, says practical concession is not the same as abandoning beliefs. He says extremists with an all-or-nothing mindset pose as great a threat to the movement as vigilantes.

He says there is a difference between “ethical compromise and a political compromise.” Koop, in the 1984 Baby Doe case, wrote a compromise, broadening the definition of child abuse to include medical neglect of handicapped infants. He says that if he had pushed to safeguard all infants in every possible medical circumstance, there never would have been an agreement. “By insisting on everything, many times we end up with nothing.”

Koop regards the Roe decision as a failed effort at conciliation: If pro-life advocates had allowed for abortion in cases of rape and incest rather than demanding a ban on all abortions, a sweeping court ruling such as Roe would have been avoided, or at least delayed. “A compromise could have averted millions upon millions of abortions.”

Yet, Terry puts the blame for abortion squarely on “lazy and powerless” church leaders who refuse to teach self-denial and are eager for acceptance by the world. “Apathy of the Christian community has paved the way for the success of the child-killing movement.”

Political realities

This fall, in what many pro-lifers view as a major political victory, Congress renewed the Hyde Amendment, but only after adding exemptions in rape and incest cases.

In light of Clinton’s election and a Democratic Congress, many predicted the repeal of Hyde, which has prevented use of Medicaid funds for abortion—except to save the mother’s life—since 1976.

“We were convinced we couldn’t win without including rape and incest [exceptions],” says Rep. Henry Hyde (R.—Ill.). “We had resisted all these years, but we felt to save the 99 percent we had to compromise, so we did.”

Wanda Franz, president of the National Right to Life Committee in Washington, D.C., says pro-lifers must be more flexible in realizing certain goals are no longer achievable because White House access has been lost.

But to Judie Brown, president of American Life League (ALL) in Stafford, Virginia, political compromise on the Hyde Amendment remains unacceptable. “You can’t provide a list of babies that it’s okay to kill.” ALL has emphasized the building of grassroots support rather than legislative action since Clinton’s election. ALL membership has risen to 300,000, an increase of 50,000, in the past year.

The pro-life movement’s morale may have reached its nadir on Clinton’s third day in office—and the twentieth anniversary of Roe v. Wade—when he issued executive orders to end restrictions on fetal-tissue research, abortion counseling at federally assisted family-planning clinics, and study of the abortion pill RU 486.

In spite of the President’s actions, abortion-rights advocates themselves are far from unified. Early this year, many predicted quick passage of the Freedom of Choice Act (FOCA). When a House panel advanced FOCA in May, it added provisions allowing the 39 states with abortion restrictions to keep some of those in place. FOCA fell apart because some lawmakers and abortion-industry principals insisted on a no-exceptions victory, showing that they, too, have difficulty accepting compromise.

A recent Gallup Poll commissioned by the Chicago-based Americans United for Life (AUL) shows how divided Americans are about abortion: more than three-fourths believe abortion is murder, yet a majority also believe abortion should be a woman’s right, unfettered by government.

Pro-life strategies splinter

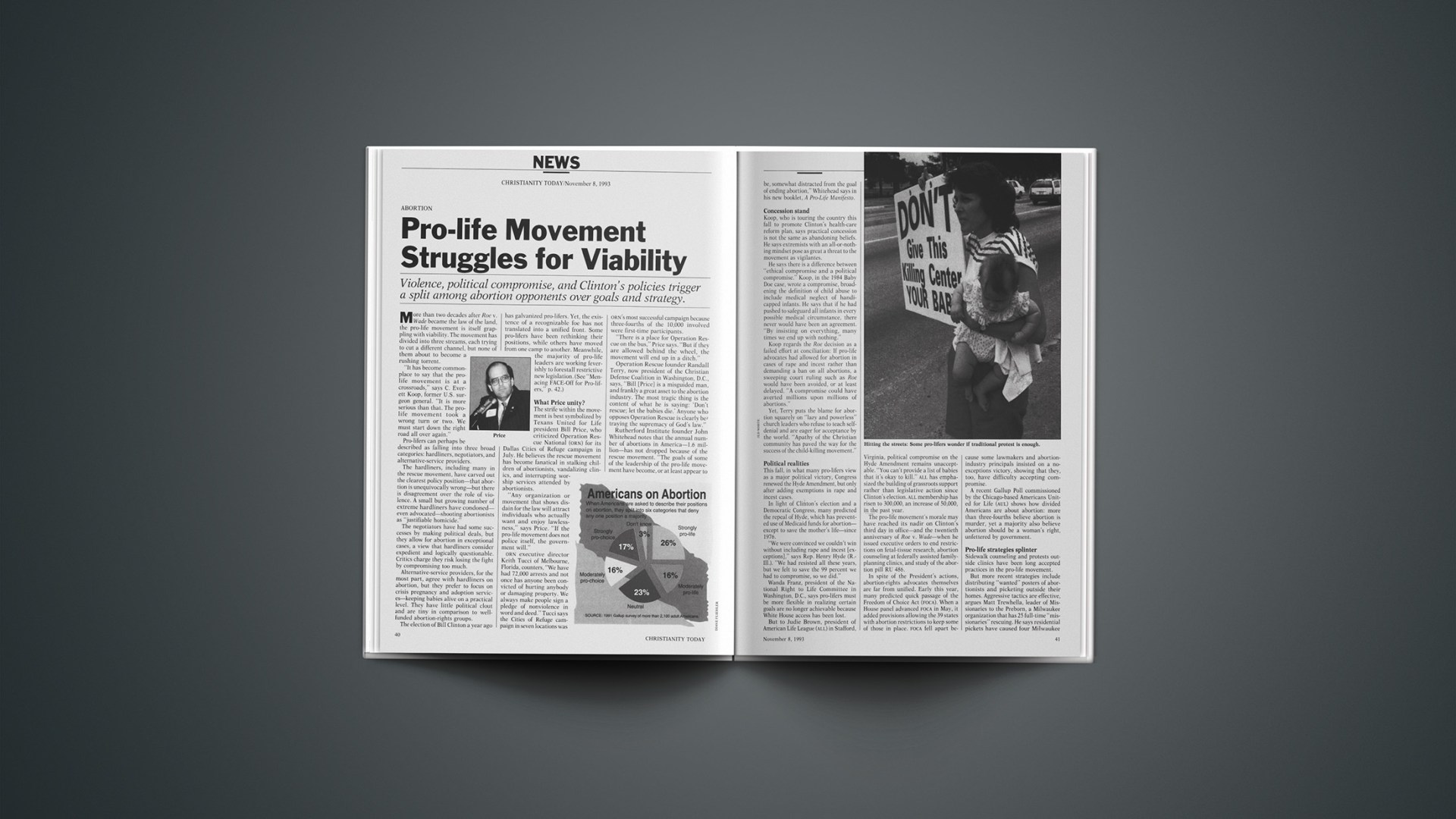

Sidewalk counseling and protests outside clinics have been long accepted practices in the pro-life movement.

But more recent strategies include distributing “wanted” posters of abortionists and picketing outside their homes. Aggressive tactics are effective, argues Matt Trewhella, leader of Missionaries to the Preborn, a Milwaukee organization that has 25 full-time “missionaries” rescuing. He says residential pickets have caused four Milwaukee abortionists to quit the business.

Bombings and arsons at abortion centers have become the calling card of pro-life extremists. But this year’s shooting of abortionists was unprecedented. The murder in March of abortionist David Gunn in Pensacola, Florida, and the shooting in August of George Tiller in Wichita, Kansas, more than anything else has splintered the pro-life movement.

Shelley Shannon, scheduled to go on trial this month for the attempted murder of Tiller, had participated in Advocates for Life rescues in Portland, Oregon, along with founder Andrew Burnett. She also had been part of the 1991 Summer of Mercy campaign in Wichita by Operation Rescue, which targeted Tiller’s abortion center. “Children who are dying in abortion clinics are real people,” says Burnett. “What Shelley did is consistent with that thinking.”

AUL president Paige Comstock Cunningham says, “Civil disobedience is a part of our national heritage, but where I draw the line is violence and intimidation.”

While Cunningham speaks for most pro-life leaders, Burnett traces his beliefs to the sixth commandment and Mosaic laws. “We see in Scripture that there can be a use of lethal force in defending another life. There is such a thing as justifiable homicide in this country.”

Paul Hill, who founded Defensive Action in Pensacola shortly after what he calls “the alleged murder” of Gunn, cites Jesus’ command to love your neighbor as yourself. “Unborn children are our neighbors,” says Hill. “Preventing murder is clearly prescribed.”

Menacing Face-Off For Pro-Lifers

For all the division in the right-to-life movement, pro-lifers are universally condemning one threat: the Freedom of Access to Clinic Entrances Act (FACE), which is pending in Congress. Pro-life groups staged a lobbying effort last month in Washington, D.C., to protest the proposed legislation.

The bill would make it a federal crime to “prevent or discourage” abortion by impeding clinic “ingress or egress.” The law would allow women to sue for damages, and first-time offenders could be imprisoned for up to a year, ORN executive director Keith Tucci says, “Grandma attempting to talk on a sidewalk will be guilty of a federal crime.”

FACE gained steam after the killing of abortionist David Gunn, but prolife leaders say violent rhetoric is a red herring. They say activism outside clinics has disrupted the income of abortionists inside, both causing the number of appointments to drop and resulting in more medical complications.

Pro-lifers say the bill is draconian because it punishes only one form of dissent—that against abortion. Picketers in labor disputes, homosexual-rights rallies, or save-the-environment marches would not be affected. “We are being singled out for our politically incorrect speech and actions,” says Operation Rescue founder Randall Terry. “Why is the false ‘constitutional right’ of child killing suddenly more sacred than all other constitutional rights?”

Pro-life leaders admit FACE would cause the number of rescuers and picketers to decline, but warn it could backfire on the abortion industry. Tucci says, “When you crush nonviolent people, violent people are waiting in the wings.”

NOW v. Scheidler

Violence is not limited to the pro-life movement. Joseph Scheidler, founder of the Pro-Life Action League in Chicago, has been beaten by a crowd, had office windows shot out, and door locks at home glued shut.

Scheidler says the shootings of abortionists have hurt the image of the prolife movement. Converting abortionists to the pro-life cause is more effective, he says, noting that 17 have crossed over.

Scheidler is the defendant in a case to be argued before the U.S. Supreme Court this fall, NOW v. Scheidler. Even though he won in two lower courts, the Justice Department has revived a Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organization (RICO) suit, dating back to 1986. “They say I conspired to use intimidation and extortion in keeping women from their most basic right—killing their baby.” NOW must prove Scheidler has profited economically. If he loses, Scheidler conceivably would be forced to pay triple damages to every abortion facility in the country for losses they might have incurred because of his activism.

A call to compassion

Koop says the pro-life movement erred in treating abortion as just another legal issue rather than a moral one. “As we have seen with tobacco and alcohol, moral suasion can work better than prohibition,” Koop says.

Cunningham says the perception of pro-lifers as being self-righteous, uncompassionate, and intolerant must change. “Women who have aborted do not feel accepted by the pro-life movement,” Cunningham says. “What a tragedy that the church is the last place a woman who has aborted would come to.”

Former AUL president Guy Condon, now president of Care Net in Falls Church, Virginia, says abortion on demand is a result of a crisis in the church. He cites an Alan Guttmacher Institute survey showing nearly three-fourths of women obtaining abortions belong to a “community of faith,” with one out of six describing herself as evangelical.

Care Net, formerly the Christian Action Council, has helped establish 450 crisis pregnancy centers in North America. In the United States, there are nearly 4,000 crisis pregnancy centers, most operating independently. However, many are little more than hotline counseling and referral services.

Condon says, “What’s needed is a word of healing. If we are effective in loving a woman in a crisis, she will love her baby.” While such organizations try to win the hearts of pregnant women, pro-life hardliners and negotiators plug away in the political realm.

A coordinated effort to battle abortion seems far off. Negotiators fret that the behavior of the hardliners will only hasten the passage of laws outlawing any restriction on abortion. Hardliners think the negotiators have lost touch. If they are limited legislatively in trying to stop abortion, those who are frustrated may resort to doing what women seeking an abortion did before 1973—break the law.

By John W. Kennedy.