“When local merchants wanted to meet Saint Paul, they asked the Christians where to find him,” recounted our tour guide during a recent trip to Turkey. “The Christians said, ‘Go out on the way to Lystra and look for a man of short stature, with a crooked nose, hollow eyes, and a face like an angel.’ “

We were also “on the way” to see Paul. Not to Lystra, but to modern-day Konya (formerly Iconium, near Lystra)—another of the apostle’s haunts. And the Christians on our tour, like those first-century merchants, wanted a glimpse of Paul’s world. That’s not easily done in this country where minarets pierce the skyline in places where Paul’s footprints have long since disappeared.

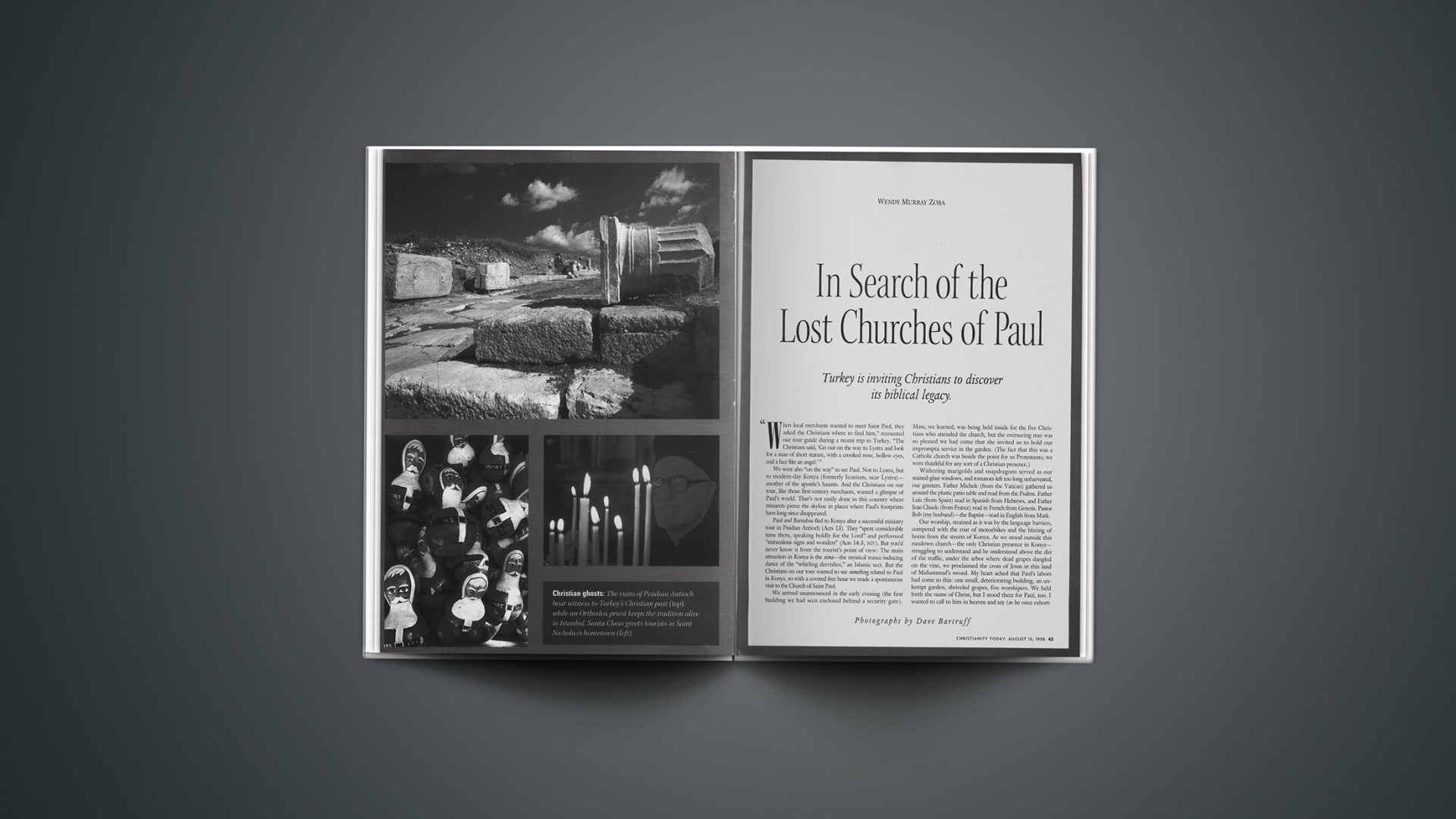

Paul and Barnabas fled to Konya after a successful ministry tour in Pisidian Antioch (Acts 13). They “spent considerable time there, speaking boldly for the Lord” and performed “miraculous signs and wonders” (Acts 14:3, niv). But you’d never know it from the tourist’s point of view: The main attraction in Konya is the sema—the mystical trance-inducing dance of the “whirling dervishes,” an Islamic sect. But the Christians on our tour wanted to see something related to Paul in Konya, so with a coveted free hour we made a spontaneous visit to the Church of Saint Paul.

We arrived unannounced in the early evening (the first building we had seen enclosed behind a security gate). Mass, we learned, was being held inside for the five Christians who attended the church, but the overseeing nun was so pleased we had come that she invited us to hold our impromptu service in the garden. (The fact that this was a Catholic church was beside the point for us Protestants; we were thankful for any sort of a Christian presence.)

Withering marigolds and snapdragons served as our stained-glass windows, and tomatoes left too long unharvested, our greeters. Father Michele (from the Vatican) gathered us around the plastic patio table and read from the Psalms. Father Luis (from Spain) read in Spanish from Hebrews, and Father Jean Claude (from France) read in French from Genesis. Pastor Bob (my husband)—the Baptist—read in English from Mark.

Our worship, strained as it was by the language barriers, competed with the roar of motorbikes and the blaring of horns from the streets of Konya. As we stood outside this rundown church—the only Christian presence in Konya—struggling to understand and be understood above the din of the traffic, under the arbor where dead grapes dangled on the vine, we proclaimed the cross of Jesus in this land of Muhammad’s sword. My heart ached that Paul’s labors had come to this: one small, deteriorating building, an unkempt garden, shriveled grapes, five worshipers. We held forth the name of Christ, but I stood there for Paul, too. I wanted to call to him in heaven and say (as he once exhorted the Corinthians): “Your labors were not in vain!”

How could so rich a Christian heritage be so strikingly disenfranchised? Turkey is second only to Israel in the number of biblical sites it offers to Christian pilgrims. Noah’s ark landed here! (Mount Ararat commands pride of place in the mountains of eastern Turkey.) Turkey was once the land of the Hittites, which the Lord promised to Joshua (1:4). Many who gathered in Jerusalem for Pentecost when the Spirit gave birth to the church had traveled from what is today Turkey (“Cappadocia, Pontus, and Asia, Phyrgia and Pamphylia,” Acts 2:9-10). Peter’s first epistle—addressing the suffering Christians “scattered throughout Pontus, Galatia, Cappadocia, Asia, and Bithynia”—went to Turkey. Paul was born here; he spent the majority of his active ministry here. The apostle John lived the latter part of his life here and, tradition says, buried Jesus’ mother here in Ephesus. When the Lord gave him the vision in Revelation, with a message for the “seven churches” (Rev. 1:11) exhorting them to “overcome,” all of these congregations were located in what is now Turkey.

Beyond the biblical heritage, the early church fathers bequeathed a rich Christian legacy to Turkey. Polycarp, a direct link to the apostle John, became bishop of Smyrna (modern Ismir) in the early second century; Irenaeus, probably a native of Smyrna, sat under Polycarp and emigrated to Lyons where he became bishop in the late second century. In the third century, Gregory the Wonder Worker was appointed bishop of Pontus (northern Turkey); in A.D. 325 the Nicene Creed was fashioned in Nicea (present-day Iznik); in A.D. 330 Constantine moved the seat of the empire to Constantinople (Istanbul); in the late fourth century Basil of Caesarea, his brother Gregory of Nyssa, and friend Gregory of Nazianzus (a.k.a. “the Cappadocian fathers”) brought final shape to the doctrine of the Trinity (helping to overthrow the Arian heresy); in A.D. 398 John Chrysostom was reluctantly consecrated archbishop of Constantinople; and the original “Santa Claus”—Bishop Nicholas of Myra—made his home on Turkey’s southern Mediterranean coast, also during the fourth century.

Christians fleeing persecution in these early centuries found shelter in the rugged Cappadocian “fairy chimneys” in central Turkey. Inside these bizarre jutting rock formations—eroded tufa and volcanic ash enveloped in basalt that look like something out of Star Wars—magical frescoes, carved archways, baptismal pools, dining tables, and living quarters have been cut out of the rock. Christians also set up house in “the underground city” elsewhere in Cappadocia, a seven-story inverted “skyscraper” where they lived during some of the worst seasons of persecution.

But the present-day abundance of Turkish carpets, minarets, and Qur’anic calligraphy that I saw everywhere compelled me to conclude painfully that Paul’s congregations, the seven churches in Revelation, and the suffering Christians in hiding evidently did not “overcome.”

Secular versus religious The Turkish government is offering Paul’s lost legacy a chance for resurrection. It has been posturing itself for admission into the European Union (EU) and trying to win acceptance in the West generally. Turkey’s leaders recognized the importance of projecting their society as fully democratic, tolerant, and embracing of all forms of belief—particularly those identified with the West, which includes Christianity. Their hopes were dashed last December when the EU blocked Turkey’s admittance, citing (among other things) its inability “to overcome serious human rights problems.”

Despite rejection by the EU, Turkey is still a virtual gold mine for tourist dollars. Europeans have long indulged themselves vacationing along the country’s still pristine Mediterranean coastline. But the Turkish government has only recently tapped the tourist potential their biblical sites promise. As the Israel Government Tourist Office will attest, Christians make great tourists in the land of the Bible. And as Turkey’s ministry of tourism is waking up to that fact, Christians are being beckoned to come to Turkey and recover their lost legacy. Ertug-rul Dokuzog-lu, the governor of Isparta, where the ruins of Pisidian Antioch are found, asked us as we left the ruins of the synagogue where Paul preached: “What do you feel, being here where Saint Paul was?”

One woman had been so overcome with emotion when my husband read from Acts amidst the ruins of the synagogue that she burst into tears. Father Michele expressed frustration that, after being so overtaken by emotion, Christians had no place to go where they could respond in worship.

The governor seemed genuinely affected. “We agree that there is no building for the Christians to pray. That is because no Christians live here. But there are two churches [nearby] waiting to be rebuilt. I want them to be rebuilt and used and visited.” (He then invited and challenged us to come back to do so.) Ibrahim Gurdal, the Turkish government’s minister of tourism, echoed the governor’s sentiment: “We want you [Christians] to see your past. You are our brothers and sisters.”

But this is where Turkey’s ideological war with itself asserts itself and betrays its contradictions. Prospective Christian tourists are assured, says Gurdal, that people of faith are welcome and have complete freedom. They are “brothers and sisters.” Yet Christianity still makes many squirm. The government’s aggressive commitment to secularization has resulted in policies outlawing “propaganda” and “missionary” activity of a religious nature. Christians (and fundamentalist Muslims) have acutely felt this pressure. The government has resisted the pleas of the Ecumenical Patriarch (Bartholomew I, archbishop of Constantinople, New Rome) to reopen the only Orthodox seminary (closed in 1971). In January, a second violent assault against Eastern Orthodox holy sites occurred in Istanbul, this time involving the murder of a custodian. Since then, some Orthodox Christians, including the archbishop, are questioning the government’s commitment to protect their presence. And beyond this, save for a single administration in Turkey’s modern history, that of Damad Ferit Pasha, the government has yet to acknowledge the Armenian genocide (1915-16), which remains a bitter point of hostility between them and their Armenian Christian “brothers and sisters.”

Turkey’s premier historical monument, Hagia Sophia, serves as a metaphor for this country’s conflicted identity. The 1,460-year-old “crowning glory”—at one time the central church in the Byzantine empire and later a great mosque where the Ottoman sultans were crowned—is now listed by the World Monument Watch on the list of “the world’s most endangered heritage sites.” Its dome and pillars and priceless mosaics remain in a state of steady deterioration, due either to a lack of funds or a lack of will to restore it (admission fees go straight to Turkey’s capital, Ankara, for general expenses). Says Stephen Kinzer in the New York Times, the Hagia Sophia “is at the heart of battle that … still burns in the minds of many people in the eastern Mediterranean: Who owns Istanbul, Christians or Muslims?”

The road to secularization This cultural schizophrenia has arisen, as noted, out of the country’s wrenching history. A museum on Turkey’s southern Mediterranean coast offers a visible lesson in this conflicted history. The first room yields rustic pots and jars, pins and coins from the Old Stone Age and the Hittite period. This quickly gives way to expansive galleries of armless, sometimes headless, marble ghosts of Greece and Rome. Beyond this, and off to the side, there is a small darkened room where the relics of Saint Nicholas, from nearby Myra, are housed along with Byzantine icons and ornate Bibles. Then everything changes when the visitor enters room upon room of carpets, Qur’anic calligraphy, sultans’ gowns, and swords. (You could almost hear the hoofbeats of the Seljuk and Ottoman Turks.)

The defeat of the Ottoman Empire at the end of World War I meant that the proud, fierce Ottomans were forced to relinquish portions of their territory (including Istanbul) to the British, French, Italians, and Greeks. This excited the dormant nationalist impulse in Turkey, which military hero Mustafa Kemal (“the only hero the Turks had left”) seized upon. General Kemal, recognizing his country’s weakened and demeaned position, gathered a cohort of like-minded thinkers, aroused nationalistic sentiment, consolidated military support, and renounced rank and titles to set up his makeshift government in Ankara. He was determined to secularize the nation and break Islam’s stranglehold on the culture.

He convened the first meeting of the Grand National Assembly (GNA) in April 1920. After solidifying his standing as the new leader (sending the last of the sultans into exile) and eventually wresting the territories from their foreign occupants, Kemal secured Turkey’s sovereignty in a peace treaty signed in Lausanne in July 1923. (The event was covered by a Toronto Star journalist named Ernest Hemingway.)

A few months later the GNA unanimously endorsed the proclamation for the Republic of Turkey, and Kemal began the herculean task of dismantling the Umma (the strict Muslim identity) and building a new, secular nation.

This required a “new interpretation” of Islam. Kemal abolished the caliphate (the sultans) and banished all males of the royal family; secularized education, banning convents run by religious sects (including “the whirling dervishes”); discarded the Arabic script for the Roman alphabet; banned the turban and the fez (the headgear of officials); encouraged women to enter the professional class; and made the adoption of surnames obligatory. The GNA gave him the surname “Ataturk” (father of Turks).

Turkey has followed the trajectory toward modernization ever since, though Ataturk’s methods have been modified over time. (His one-party government made strides toward a more democratic system in the 1950s when a multiparty system was introduced.) But they are still experiencing “growing pains.” In elections in 1996, the extreme right-wing Muslim Welfare party candidate, Necmettin Erbakan, won with only a 21.3 percent plurality. Fearing a resurgence of Islamic fundamentalism, the military quickly forced him from office, and Mesut Yilmaz of the Motherland party now serves as prime minister.

Traveling in Turkey

Hos, geldiniz! (“Welcome to Turkey”)—”the dividing line between the Orient and Occident.” Since the dawn of civilization, this land mass of mountains, plateaus, and river valleys has been integral to the rise and fall of many nations. The scope of touring possibilities in this mysterious and multifaceted landscape is endless, especially for the Christian pilgrim. Below are some helpful travel tips.

—Language. Thanks to Ataturk’s reforms, the Turkish language uses the Roman alphabet (with an abundance of Ks, Zs, and curious additional markings), so reading signs and navigating roadways can be managed with the help of a phrasebook or dictionary. Many Turks have undertaken an independent study of English, but an English-speaking guide is a must.

—Money. Exchanging American dollars for Turkish lira (TL) can be a formidable challenge. The exchange rate (at the time of publication) is 270,000TL to the dollar. You can’t get by without a calculator—and even then your head will spin at the first several attempts at purchasing.

—Size. Turkey encompasses 300,000 square miles, 3 percent in Europe and 97 percent in Asia. The Black Sea lies to the north, with the Mediterranean to the south. Greece and Bulgaria border Turkey to the northwest, Georgia and Armenia to the northeast, Iran to the east, and Iraq and Syria to the southeast.

—Biblical and historical sites. Istanbul (still called Constantinople by the Orthodox Christians) once stood as the center for Christendom under Constantine. The seven churches of Revelation (in the western and central portions) include modern-day Bergama (Pergamum), Akhisar (Thyatira), Alasehir (Philadelphia); Sart (Sardis); Pamukkale (Hierapolis, which is near Laodicea); Efes (Ephesus); and Izmir (Smyrna). Mount Ararat is in the east, Paul’s birthplace of Tarsus, along with Myra and Patara (the birthplace and home of Saint Nicholas), are on the Mediterranean coast. Pisidian Antioch and Iconium, two haunts of Paul’s, are found in central Turkey (Yalvac and Konya, respectively), and the Cappadocian fairy chimneys, also in central Turkey, offer a glimpse into the life and struggles of the early church.

—Be warned. The cliche “He smokes like a Turk” is well-deserved. “No Smoking” sections seem not to exist in Turkey—or on Turkish Airlines.

This intentional secularization has resulted in a strange concoction of moderate Islam mingled with fierce Islamic nationalism (not to be confused with “fundamentalism”). From a religious vantage point, the more developed areas of the country embrace Islam nominally—more culturally than religiously. Our guide said (to my shock), “Islam means nothing.” And in its effort to keep modernization on track, the government encourages this nominalism and, in fact, limits certain religious expressions. Last March the government proposed legislation that would curb radical Islam by limiting the building of mosques and creating harsher penalties for violating the secular dress code.

This has resulted in a surprising show of force and solidarity by progressive Islamic women, many of whom are professionals and would be considered “modern,” but who are demanding the right to wear—of all things—their headcoverings (presently forbidden in many public places, like the university). “Instead of a symbol of subservience to men, many Islamic feminists view the scarf or the veil as a guard against the intruding eyes of men and as a sign that their first allegiance is to God—not to their husbands or fathers,” writes Philip Smucker in U.S. News & World Report.

The first principle of the Turkish government is to maintain internal stability at all costs. This has meant that there remains a fierce unwillingness to allow any “extreme” religious expressions to flourish for fear of introducing political instability. In that sense, “the Kurds, the communists, the Islamic fundamentalists, and the Christians are often all lumped together,” notes Andy Jackson, founder of the International Turkey Network of Phoenix, Arizona. All threaten internal stability.

The lukewarm religiosity has also incited the fervor of the traditional, or “extreme,” Muslims, who compose 5 to 6 percent of the population (another source puts them closer to 10 or 20 percent). As the 1996 elections demonstrated, they are a force to be reckoned with.

All of this has conspired to keep the Christian population negligible. The Greek, Armenian, Syrian, and Arab Christian populations together make up less than 1 percent of the population (maybe 50,000 out of more than 65 million people). The number of “evangelical” Christians is even harder to calculate. Roger Maldsted, who has worked in Turkey since 1961, estimates that there have been about 750 Turkish converts to Christ in the 30-plus years he has been there, with 500 of those conversions occurring within the last five or six years. Andy Jackson estimates that the number of Turkish believers who belong to some form of regular indigenous fellowship (where Turks with Muslim backgrounds, not missionaries, are the leaders) hovers around 600. He estimates there are approximately 14 indigenous Turkish fellowships, with 50 to 60 members each. The “secretive” believers who have not publicly affiliated themselves with a church number anywhere from 1,000 to 3,000.

Small as these numbers are, it is a vast improvement over the number of converts 30 years ago when there was only a handful of evangelical Christians (some estimates put it between 10 and 50). The first Protestant church was registered in 1988, and in 1995 the government officially recognized evangelical churches. So the gospel is making inroads, even if at a torturously slow pace.

At the same time, many younger, more modernized Turks are looking for spiritual answers. One young Turk told me: “Nominal Islam is pervasive because Arabic is used in the mosques and most young people can’t read it. Our Qur’an is in Arabic, but young people want to learn it in Turkish.” Nevertheless, many of the younger Turks who want to learn the Qur’an in Turkish are not interested in a strict interpretation of Islam: “We don’t have this kind of Islamic concept,” he said. “I believe in God, but I do not have much sympathy for Islam.”

Western ideas are also infiltrating the culture (for better or worse), which is similarly eroding Islamic allegiances. Our guide told us about his sister, who was studying at Bryn Mawr College in Pennsylvania. He lamented (shaking his head): “All that women’s liberation stuff has made her very tough.”

The disillusionment with nominal Islam, the encroaching Western ideas, and general spiritual hunger have given the up-and-coming generation of Turks new ears with which to hear the good news of the gospel. The religious orientation they have been reared in, nominal though it may be, has aroused, but not satisfied, their search for spiritual answers.

Where from here? Christian tourism will not provide answers to all their questions. In fact, as Turkey awakens to the economic gold mine that Christian pilgrims can generate, there is the potential for harm to the efforts of some long-termers. Andy Jackson says that “tourism will draw in a lot of Christian crackpots who will not be incarnating the gospel” and who could adversely affect those Christians already in Turkey who are struggling to plant churches and nurture spiritual maturity in these young believers. Our guide told me he was baptized during one tour simply to allay the zealous Christians’ unrelenting badgering.

But encouraging Christian tourism, says Jackson, will ultimately help the struggling church in Turkey. It will create a less hostile, more welcoming environment to Christians generally and will put the government on the record as celebrating Christians as “brothers and sisters” (such as Minister Gurdal did before our group). In addition, it will mean more and more tour guides will have to study the New Testament in order to know the history their guests are interested in, and the Turkish government will have to produce Christian materials for pilgrims. So, on that level, Christian tourism can be God’s tool to break up the hardened ground of Turkey’s anti-Christian ethos and to prepare for seeds of the gospel to be planted and nourished by indigenous believers.

Paul reborn The Reconciliation Walk project, sponsored by Youth with a Mission, has inaugurated a four-year international effort to seek forgiveness for atrocities committed in the name of Christ during the Crusades. Representatives have been surprisingly well received in Turkey. Says Matthew Hand in Charisma, who drafted the written apology that is read to any who will listen: “We accept the blame for something we didn’t do, just like Jesus did.” Many Turks find that hard to fathom.

One person recounts that, after speaking for 45 minutes with a Turk named Rafad and reading him the document of confession, he said, “Please don’t touch my heart. It is very thin, and it will break. I want to go cry in the mosque.”

The Walk is an example of the Turkish government’s willingness to welcome Christians as part of their larger desire to become a welcomed partner in the West. Perhaps, too, it could serve as a model to help them overcome aspects of their history that have inhibited their acceptance by the West—like their less-than-sparkling human-rights record (particularly with regard to Kurds in the east) and the lingering cloud of the Armenian genocide.

Christian worker George Bellas, who has ministered to the Turkish Kurds for nine years, thinks that a public confession and corporate repentance for past sins such as has been exhibited in the Reconciliation Walk may be beyond the scope of possibility at this stage of Turkey’s evolution as a modern nation. “The Muslims do not have the basic Judeo-Christian concept of making restitution,” says Bellas. The Turks do not understand the notion of accepting blame for something they themselves didn’t do and certainly not based on doing something “just like Jesus did.”

That is because they are only just beginning to hear about what Jesus did—an irony, since so many of the New Testament churches were born here and so much of the theological foundation of the faith was established here.

But hearing it all over again for the very first time is better than not hearing it at all. Regardless of their profit motive, the Turkish government wants Christians to come. And for all its potential complications and theological hazards, Christian tourism is helping to create an environment for this country—with its checkered history and fragmented identity—to rediscover its Christian heritage.

I thought of Paul another time when I was in Konya as I talked with a young Turk in a spot not far from where Paul himself stood when he “preached boldly about the grace of the Lord” (Acts 14:3). The young man was assailing me with a battery of questions about Christianity.

“Do Christians believe in reincarnation?” he asked.

I told him about the Christian belief in resurrection.

“How is this possible?” he asked.

I explained how Jesus made it possible for everyone.

“How did he do this?” he asked.

“Well,” I said, “after he was executed his friends buried him in a cave, but they had to rush because the Sabbath was about to start. So they waited another day, and then went back to the grave on the third day, to finish the burial preparations.

“When they approached, they noticed that the grave entrance was open. So they went in and saw that the body was gone.”

“Where was it?” he asked.

“He came back to life,” I said. “He wanted everyone to understand that he, alone, was sent by God. He appeared to hundreds of people.”

The young man’s eyes burned with astonishment.

“Did this really happen?” he said.

Copyright © 1998 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.