In the history of modern evangelical enthusiasms, Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ seems to be joining WWJD bracelets and Promise Keepers’ conferences as cultural markers. At first it seemed like it might just be a quirky art film: a film about Jesus’ passion using only Aramaic and Latin—and with no subtitles.

But what started out as news of the weird has turned into a powerful and popular film that is likely to be a major milestone in cinematic history. Gibson has filmed the Passion with his trademark force—and for those whose ancient language skills are a bit rusty, he has added subtitles. In January, Gibson told CHRISTIANITY TODAY that the film had already been scheduled to open on close to 3,500 screens—that places it squarely between Finding Nemo and Return of the King at their peak distribution last year. When the film opened on February 25, it was showing on 4,643 screens in 3,006 theaters.

Promoters have produced a Passion lapel pin and witnessing card. Endorsements have poured in from evangelical leaders like Focus on the Family president Donald Hodel and Harvest Crusades evangelist Greg Laurie. Public figures as diverse as Willow Creek Community Church’s pastor Bill Hybels and bluegrass musician Ricky Skaggs have hosted special screenings for pastors. Moving responses from ordinary believers and Christian celebrities have circulated widely on the Internet, urging believers to see the movie. And Tyndale House has reinforced the movie’s influence by publishing The Passion, a coffee table book that integrates still photos from the filming with a harmony of the Passion accounts drawn from the New Living Translation. (Many illustrations for the March 2004 issue of CT came from that book.)

This evangelical enthusiasm for The Passion of the Christ may seem a little surprising, in that the movie was shaped from start to finish by a devout Roman Catholic and by an almost medieval Catholic vision. But evangelicals have not found that a problem because, overall, the theology of the film articulates very powerful themes that have been important to all classical Christians.

The vision thing

Mel Gibson is in many ways a pre-Vatican II Roman Catholic. He prefers the Tridentine Latin Mass and calls Mary co-redemptrix. Early in the filming of The Passion, he gave a long interview to Raymond Arroyo on the conservative Catholic network EWTN. In that interview, Gibson told how actor Jim Caviezel, the film’s Jesus, insisted on beginning each day of filming with the celebration of the Mass on the set. He also recounted a series of divine coincidences that led him to read the works of Anne Catherine Emmerich, a late-18th, early-19th-century Westphalian nun who had visions of the events of the Passion. Many of the details needed to fill out the Gospel accounts he drew from her book, Dolorous Passion of Our Lord.

Here is one such detail from Emmerich:

“[A]fter the flagellation, I saw Claudia Procles, the wife of Pilate, send some large pieces of linen to the Mother of God. I know not whether she thought that Jesus would be set free, and that his Mother would then require linen to dress his wounds, or whether this compassionate lady was aware of the use which would be made of her present. … I soon after saw Mary and Magdalen approach the pillar where Jesus had been scourged; … they knelt down on the ground near the pillar, and wiped up the sacred blood with the linen which Claudia Procles had sent.”

Gibson does not follow Dolorous Passion slavishly, and at many points he chooses details that conflict with Emmerich’s account. But the sight of Pilate’s wife handing a stack of linen cloths to Jesus’ mother allows Gibson to capture a moment of sympathy and compassion between the two women, and the act of the two Marys wiping up Jesus’ blood gives Gibson the opportunity to pull back for a dramatic shot of the bloody pavement.

Evil unmasked

Another detail picked up from Dolorous Passion is just as dramatically powerful, but much more significant theologically. Emmerich writes that during Jesus’ agony in the garden, Satan presented Jesus with a vision of all the sins of the human race. “Satan brought forward innumerable temptations, as he had formerly done in the desert, even daring to adduce various accusations against him.” Satan, writes Emmerich, addressed Jesus “in words such as these: ‘Takest thou even this sin upon thyself? Art thou willing to bear its penalty? Art thou prepared to satisfy for all these sins?'”

Gibson shows Jesus being tempted by a pale, hooded female figure, who whispers to him just such words, suggesting that bearing the sins of the world is too much for Jesus, that he should turn back. And from under the tempter’s robe there slithers a snake. In a moment of metaphorical violence drawn straight from Genesis 3:15, Jesus crushes the serpent’s head beneath his sandaled heel.

These details from the film’s opening sequence announce Gibson’s acute consciousness of the cosmic battle between good and evil—between God and the devil—that is played out behind earthly scenes of violence against the innocent Jesus. Gibson’s approach to evil impressed at least one expert: The Washington Post reported last July that The Exorcist author William Peter Blatty called the movie “a tremendous depiction of evil.”

At the January pastors’ screening at Willow Creek in Illinois, Gibson explained why he used this veiled female figure to portray evil. Evil “takes on the form of beauty,” Gibson said. “It is almost beautiful. It is the great aper of God. But the mask is askew; there is always something wrong. Evil masquerades, but if your antennae are up, you’ll detect it.”

The Apostle Paul hinted at this fact in 2 Corinthians where he wrote that “Satan himself masquerades as an angel of light.” Paul said we shouldn’t be surprised then “if his servants masquerade as servants of righteousness.” C. S. Lewis had a similar insight, expressed in a letter to Arthur Greeves: “Evil usually contains or imitates some good, which accounts for its potency.”

After the screening, I asked Gibson about his belief in spiritual warfare. “That’s the big picture, isn’t it?” Gibson replied. “The big realms are slugging it out. We’re just the meat in the sandwich. And for some reason, we’re worth it. I don’t know why, but we are.”

Gibson sensed spiritual battle on the set, as well. “Complications happened to block certain things,” he said. “And the closer you are to a breakthrough point, the more vigorous it gets, so that you know when the opposition is at its greatest, you’re close and you have to keep pressing on.”

“That happened a number of times [in production], and it’s happened a number of times since.… Production was tough. Post-production has been brutal. You name it, it’s happened.… Whoa, the world goes into revolt!”

Getting personal

The world in revolt? That is, of course, the premise of the entire biblical story. Mel Gibson belongs to that group of Christians who believe we each need to personalize that fact. Not only is the world in revolt, but every human being—including Mel Gibson and David Neff—resists God and good. The visionary Emmerich wrote: “Among the sins of the world which Jesus took upon himself, I saw also my own; and a stream, in which I distinctly beheld each of my faults, appeared to flow towards me from out of the temptations with which he was encircled.”

When Gibson is accused of making an anti-Semitic film (see Michael Medved’s “The Passion and Prejudice”), he stresses that each of us is responsible for Christ’s crucifixion. “For culpability,” Gibson told a group of Chicago religious leaders last July, “look to yourself. I look to myself.”

That response hasn’t mollified certain Jewish critics, but it does reveal a lot about Gibson. In an action deeply symbolic of his sense of culpability, Mel Gibson the director grabbed the mallet and spikes from the actor who was supposed to be nailing Jesus to the cross. The cameras kept rolling as Gibson wielded the hammer to show how he wanted the nails driven. The close-up cameo of Gibson’s hands became part of The Passion.

Gibson also has a strong sense of personal salvation. He has a focused feeling, such as John Wesley possessed when he wrote in 1738 that “an assurance was given me, that he had taken away my sins, even mine, and saved me from the law of sin and death.”

One reason for Gibson’s personal sense of salvation is the way this project rescued him from himself. In his foreword to the Tyndale House book The Passion, Gibson says the film “had its genesis during a time in which [he] found [him]self trapped with feelings of terrible, isolated emptiness.” He told the pastors at Willow Creek of his “emptiness … regret, despair, pain.” At the time, a little over a decade ago, he had been neglecting his faith since he was 17—a hiatus of about 18 years. Gibson said that he had “always believed,” but that he had only prayed when he found himself “in trouble.” When you neglect prayer, he said, “you fall into chaos.” And so he turned once again to God in prayer.

Contemplating God’s wounds

When Protestants talk about prayer, they usually mean talking to God about what is on their heart and asking him to deal with life’s difficulties. When Catholics talk about prayer, they mean those same things, but they tend to include as well certain practices of contemplation and meditation.

In “The Fountain Fill’d with Blood,” Historian Chris Armstrong describes the medieval origins of Cross-centered devotion, which invited the believer to meditate on each separate event of Jesus’ passion and each individual wound on his body. Long before evangelicals like Richard Foster began to experiment with guided imagery in prayer, those devotional practices also invited believers to place themselves in their imaginations into the biblical stories. These practices became the foundation for such widely practiced traditions as meditating on the Five Sorrowful Mysteries when saying the Rosary. The structure of Gibson’s film conforms exactly to the list of the Five Sorrowful Mysteries: The Agony of Jesus in the Garden, the Scourging of Jesus at the Pillar, the Crowning with Thorns, the Carrying the Cross, and the Crucifixion and Death of Jesus. And it reveals the way that this film is for Gibson a kind of prayer.

In the foreword to The Passion, he writes that the film “is not meant as a historical documentary. … I think of it as contemplative in the sense that one is compelled to remember … in a spiritual way, which cannot be articulated, only experienced.” This contemplative devotion has been intensified during the filming of The Passion of the Christ. “This work has turned up the heat” on his prayer life, Gibson told the pastors at Willow Creek. “The past three years forced me to focus heavily on the Passion.”

“I went to the wounds of Christ in order to cure my wounds,” he told TODAY’S CHRISTIAN WOMAN, a CT sister publication, by e-mail. “And when I did that, through reading and studying and meditating and praying, I began to see in my own mind what he really went through. … It was like giving birth: the story, the way I envisioned the suffering of Christ, got inside me and started to grow, and it reached a point where I just had to tell it, to get it out.”

At the Willow Creek event, Hybels asked Gibson why so many religious films are, by comparison, not very good. “I didn’t try to make a religious film,” Gibson said by way of response. “I tried to make something that was real to me.”

All of this—the sense of one’s own sins being responsible for the Crucifixion, the sense of the enormous weight of the world’s sins on the Savior’s shoulders, the horror of the suffering that Christ endured, the way the story grew inside Gibson—accounts in part for the film’s bruising bloodiness. The extremes of brutality are not simply a translation of Gibson’s secular visual vocabulary from Lethal Weapon and We Were Soldiers into the sacred sphere.

“The enormity of blood sacrifice,” as he put it, is important to Gibson. Unlike liberal Christians (both Catholic and Protestant) who deny the importance of the shedding of blood in the Atonement, Gibson grasps firmly the sacred symbol of blood and spatters the audience’s sensibilities with it. Never one to run from a compelling symbol, Gibson presents the truth of Leviticus 17:11 in all its power: “The life of the flesh is in the blood; and I have given it for you upon the altar to make atonement for your souls; for it is the blood that makes atonement, by reason of the life.”

Some will feel simply overwhelmed by the display, but many traditional Christians (both Catholic and Protestant) will see this film and feel Gibson has sprinkled them with the saving blood just as the Israelite priests sprinkled the atoning blood on the altar. For, as Gibson puts it, “In the Old Covenant, blood was required. In the New Covenant, blood was required. Jesus could have pricked his finger, but he didn’t; he went all the way.”

What impresses Mel Gibson is the total surrender of Jesus to the Father’s will in order to be an atoning sacrifice for the sins of the human race. What rewards Mel Gibson is the silence, the introspection, the realization, and the remembering that people do. (Gibson pointed out that the Greek word for truth literally means “un-forgetting.”) After seeing the movie, one person simply said, “I’m sorry. I forgot.”

David Neff is editor of CHRISTIANITY TODAY and editorial vice president of Christianity Today International.

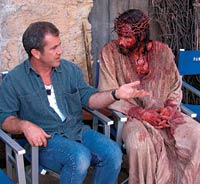

Photos by Ken Duncan. Used by permission of Tyndale House Publishers. © Icon Distribution. All rights reserved.

Copyright © 2004 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere:

A ready-to-download Bible Study on this article is available at ChristianBibleStudies.com. These unique Bible studies use articles from current issues of Christianity Today to prompt thought-provoking discussions in adult Sunday school classes or small groups.