When a pastor falls sexually, his church responds like a wife betrayed by her husband, experts say. The news of his pastor’s infidelity slammed into Jim Brown, spurring “every issue that I’ve ever seen.”

The pastor who baptized Brown’s children, preached God’s Word, and served Communion had deceived him. Months after the news, the Starkville, Mississippi, pca (Presbyterian Church in America) congregation that Brown attends stills holds late night counseling sessions to process the event, a must-do according to experts.

“People have to struggle with the fact that here was somebody who had been the mouthpiece of Christ, standing up in the pulpit as the representative of Christ,” says Brown, a medical doctor. “Members keep saying, ‘He did my marriage counseling,’ or, ‘He buried my brother.’ He had been intimately involved with all the important aspects of my life.”

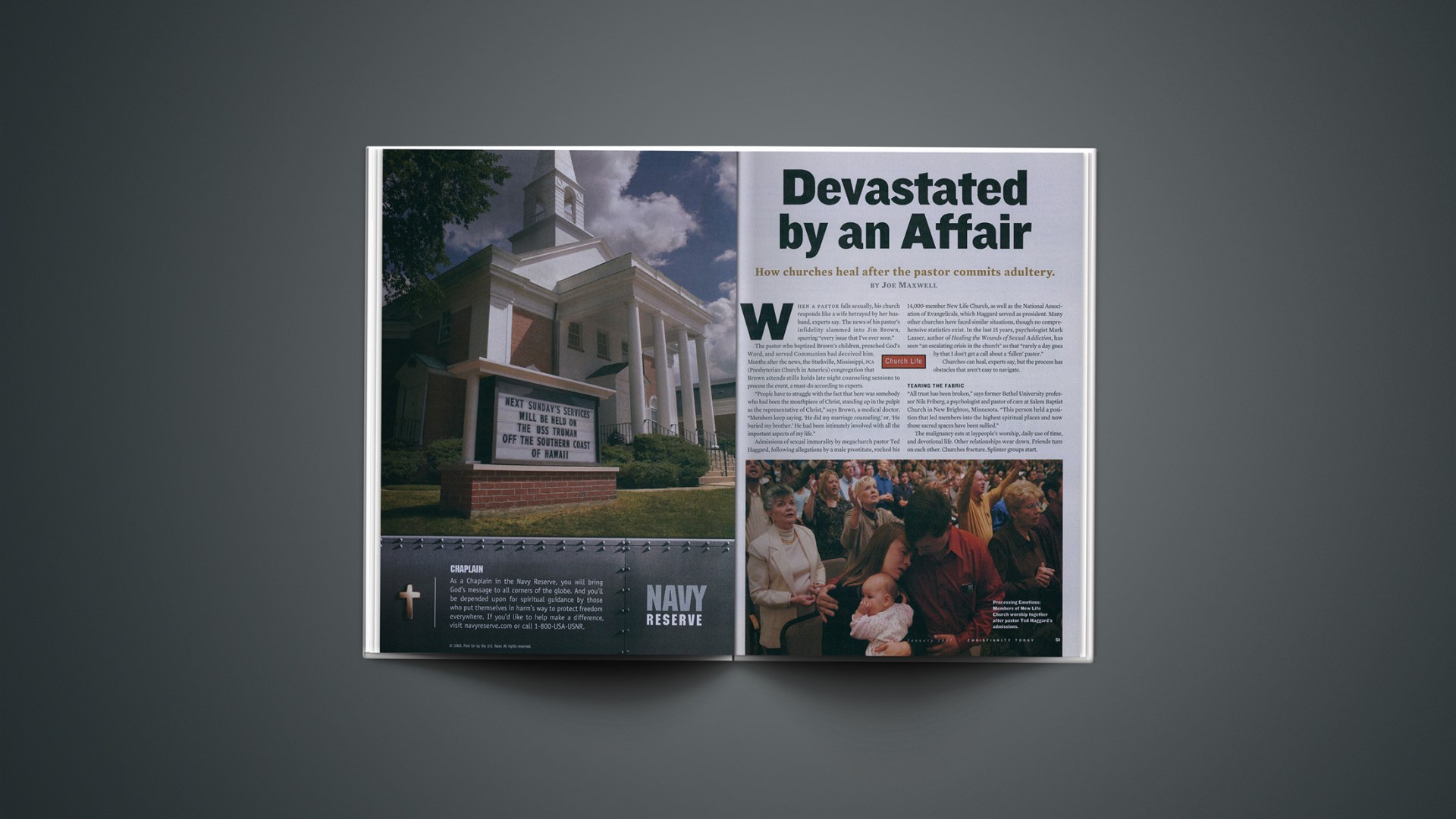

Admissions of sexual immorality by megachurch pastor Ted Haggard, following allegations by a male prostitute, rocked his 14,000-member New Life Church, as well as the National Association of Evangelicals, which Haggard served as president. Many other churches have faced similar situations, though no comprehensive statistics exist. In the last 15 years, psychologist Mark Laaser, author of Healing the Wounds of Sexual Addiction, has seen “an escalating crisis in the church” so that “rarely a day goes by that I don’t get a call about a ‘fallen’ pastor.”

Churches can heal, experts say, but the process has obstacles that aren’t easy to navigate.

Tearing the Fabric

“All trust has been broken,” says former Bethel University professor Nils Friberg, a psychologist and pastor of care at Salem Baptist Church in New Brighton, Minnesota. “This person held a position that led members into the highest spiritual places and now those sacred spaces have been sullied.”

The malignancy eats at laypeople’s worship, daily use of time, and devotional life. Other relationships wear down. Friends turn on each other. Churches fracture. Splinter groups start.

“The basic fabric of life gets torn,” says Friberg. “God seems to have let us down, since God was perceived as palpably absent during those negative events of life. In the battle between good and evil, evil seems at the moment to be winning.”

Some bodies, however, stay together and grow stronger with time, says Nancy Hopkins, an early researcher in the field and author or coauthor of several books, including Restoring the Soul of a Church.

“You are presented with a dangerous opportunity when this kind of thing happens. It is possible, if the congregation really engages and works through it, that they can emerge on the other end spiritually stronger than they were.”

After the initial shock and feelings of betrayal, other predictable initial and long-term reactions to a fallen pastor include:

• Anger and depression among most church members.

• Difficulty letting go of the fallen pastor or believing the truth of his tryst.

• Suspicion toward new leaders charged to clean up the mess.

• Irrational sympathy or antipathy for the fallen pastor.

• Blaming the predicament on support staff or on oneself for not seeing it sooner.

• Burnout among leadership or members over-invested in the event.

• Resentment and backlash toward a newly called pastor.

• Questioning personal faith or one’s faith in the church.

Laaser says at least three groups can emerge: those who want their fallen pastor back, those so angry they would never have him back, and those hoping to replace their pastor with a quick-fix, similar persona.

“They might pick somebody who is just as vulnerable to a similar problem,” Laaser says. That can be a dangerous proposition. Often, if the pastor held control of the church’s guiding board, that group cannot navigate his fall or can allow him or someone like him back into the pastorate.

Big churches often seek another charismatic leader, compounding their problem. Such leaders, says Laaser, can be “loners” who “pick out people for their elder [or accountability] boards who are themselves codependent.” This tendency may have been part of the problem in the first place.

Calling an interim pastor is a good option, says Laaser. “This gives the congregation enough time to grieve and deal with their emotions.”

However, history shows that whoever follows a fallen pastor usually is attacked, Friberg notes. He cites one church that was still lashing out at new pastors 25 years after a pastor’s fall. “There is stuff coming out from the woodwork at me and my family!” the new pastor lamented to Friberg.

Healing Steps

Meanwhile, church staff and lay leaders must keep church programs going amid the unraveling crisis. Membership usually declines, so church revenues drop. Exciting building plans and mission programs cave in, since their main promoter is now absent. Another layer of depression can result. Formerly timid opposition to novel programs suddenly grows louder, without a point man to quell it.

“If some other issue was already causing upset feelings in the congregation at the time of the revelation, the simultaneous resolution of two streams of conflict will probably be very difficult,” Friberg writes in “Secondary Victims,” a chapter in Restoring the Soul of a Church.

The best path to restoration is long-term, full disclosure.

Do not sweep the event under the rug, says Hopkins. Deal openly and thoroughly with arising issues. Let everyone speak in some way. Different people react and process differently, so don’t put a two-month or one-year time limit on the healing phase. “You’ve got one group of people who are not all feeling the same thing at the same time,” he says, “or responding the same way at the same time.”

Hopkins suggests holding congregational meetings—probably many hours at a time—where members can safely talk. Small groups with fixed rules also draw out toxic feelings. Follow-up education on grief and emotions should be set in place.

Try to get members to “broaden or to some extent ‘complexify’ the issue and not have it so focused on the sexual sin,” Hopkins says. Usually other factors are involved. Says Hopkins: It is a wonderful opportunity to deepen and enrich their spiritual life by using the event to talk about “the challenges that they are facing in their lives, the ethical and moral challenges. How does their faith impact the way they live their life and how does their faith impact the way they are going to recover from this devastating event?”

Do not proclaim forgiveness too quickly, experts caution. Often, evangelicals know to forgive but have not processed all there is to forgive. An inner frustration builds up as a result. People want “to put it all behind them,” says Hopkins, but “sometimes people will say too quickly, ‘I forgive this person.’ It is a way of staying in denial.”

Jim Brown’s Mississippi church recently called a new young pastor who was fully apprised of the challenge ahead. Months have been devoted to processing the event. Church members met recently with the pastor and a church counselor.

Bitterness. Stale orthodoxy. Broken friendships. All of those require something more than mere patches to find healing. That will be the case for New Life Church, for Brown’s church, and for others experiencing the betrayal of profound vows.

Having been through the wringer, Brown says: “You put these people on this pedestal and you put orthodoxy on a pedestal, and [then] you realize that you can speak in the tongues of men and angels, but if you lose love and grace, you lose everything.”

Joe Maxwell is a former CT assistant news editor and currently journalist-in-residence at Belhaven College in Jackson, Mississippi.

Copyright © 2007 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere:

“The Pain at New Life,” also from the January issue of Christianity Today, follows a New Life family as they deal with Haggard’s fall.

Christianity Today‘s full coverage of the Ted Haggard scandal is available on our site.

News articles on New Life’s and Ted Haggard’s recovery processes can be found on weblogs from December 1, November 21, 17, 16, 15, 13, and 6. Recent articles include:

Church looks to find its next life | Like many megachurches that have lost founders, New Life Church is in uncharted waters (The Denver Post)

New Life begins pastor hunt | With brisk efficiency, New Life Church in Colorado Springs has taken the first step toward finding a successor to disgraced Pastor Ted Haggard (Rocky Mountain News, Denver)

Shelving Ted Haggard’s marital advice | What’s in From This Day Forward, Making Your Vows Count a Lifetime (Jennifer Hunter, Chicago Sun-Times)

Arizona may figure into Haggard renewal | Exact plans for counseling are unclear (The Gazette, Colorado Springs)

Their demons make them do it | On the scale of despicableness, the hypocrite is king (Robyn Blumner, St. Petersburg Times, Fla.)

Healing the Wounds of Sexual Addiction and Restoring the Soul of a Church are available from ChristianBook.com and other retailers.