|

|

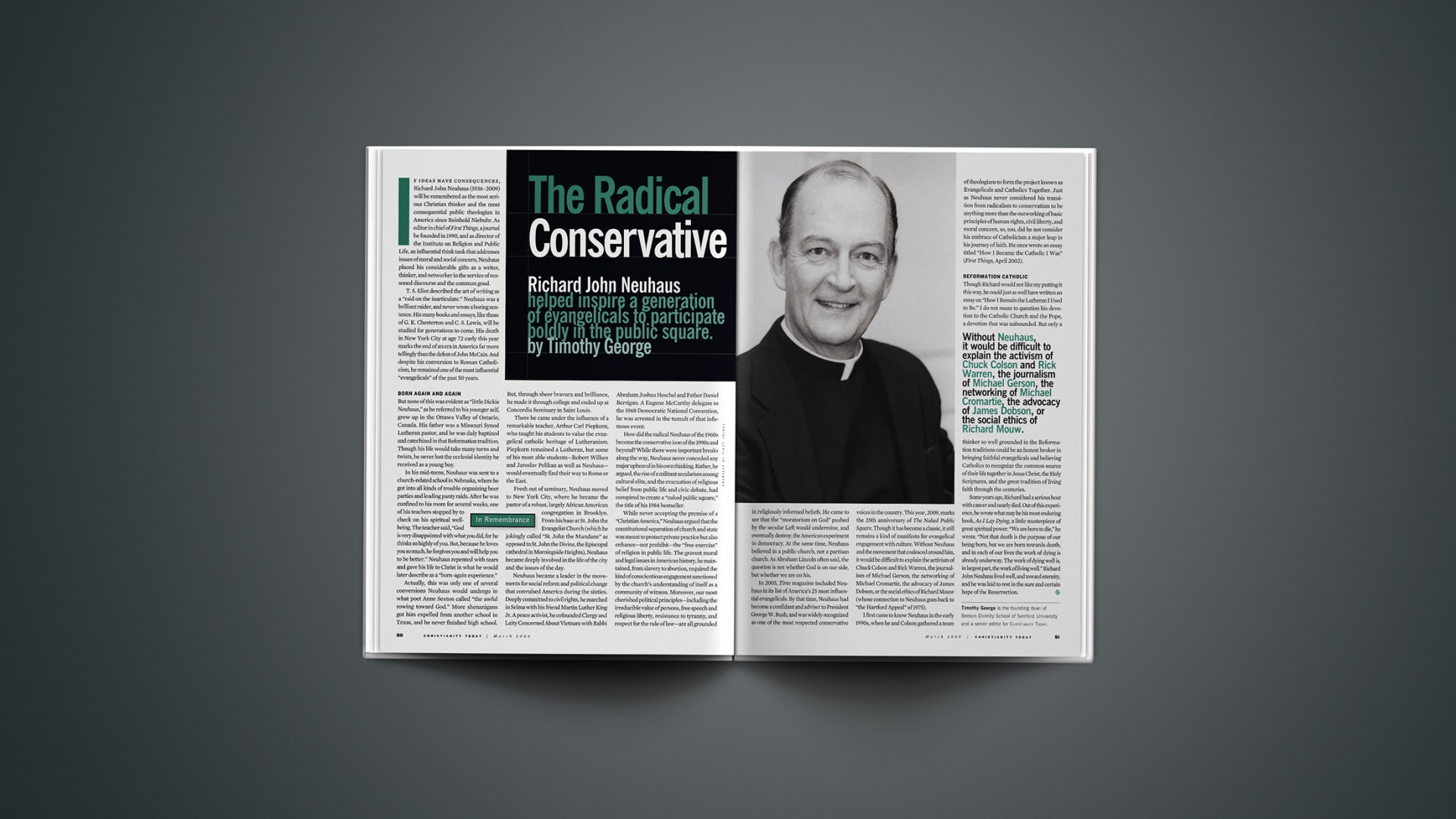

T. S. Eliot described the art of writing as a “raid on the inarticulate.” Neuhaus was a brilliant raider, and never wrote a boring sentence. His many books and essays, like those of G. K. Chesterton and C. S. Lewis, will be studied for generations to come. His death in New York City at age 72 early this year marks the end of an era in America far more tellingly than the defeat of John McCain. And despite his conversion to Roman Catholicism, he remained one of the most influential “evangelicals” of the past 50 years.

Born Again and Again

But none of this was evident as “little Dickie Neuhaus,” as he referred to his younger self, grew up in the Ottawa Valley of Ontario, Canada. His father was a Missouri Synod Lutheran pastor, and he was duly baptized and catechized in that Reformation tradition. Though his life would take many turns and twists, he never lost the ecclesial identity he received as a young boy.

In his mid-teens, Neuhaus was sent to a church-related school in Nebraska, where he got into all kinds of trouble organizing beer parties and leading panty raids. After he was confined to his room for several weeks, one of his teachers stopped by to check on his spiritual well-being. The teacher said, “God is very disappointed with what you did, for he thinks so highly of you. But, because he loves you so much, he forgives you and will help you to be better.” Neuhaus repented with tears and gave his life to Christ in what he would later describe as a “born-again experience.”

Actually, this was only one of several conversions Neuhaus would undergo in what poet Anne Sexton called “the awful rowing toward God.” More shenanigans got him expelled from another school in Texas, and he never finished high school. But, through sheer bravura and brilliance, he made it through college and ended up at Concordia Seminary in Saint Louis.

There he came under the influence of a remarkable teacher, Arthur Carl Piepkorn, who taught his students to value the evangelical catholic heritage of Lutheranism. Piepkorn remained a Lutheran, but some of his most able students—Robert Wilken and Jaroslav Pelikan as well as Neuhaus—would eventually find their way to Rome or the East.

Fresh out of seminary, Neuhaus moved to New York City, where he became the pastor of a robust, largely African American congregation in Brooklyn. From his base at St. John the Evangelist Church (which he jokingly called “St. John the Mundane” as opposed to St. John the Divine, the Episcopal cathedral in Morningside Heights), Neuhaus became deeply involved in the life of the city and the issues of the day.

Neuhaus became a leader in the movements for social reform and political change that convulsed America during the sixties. Deeply committed to civil rights, he marched in Selma with his friend Martin Luther King Jr. A peace activist, he cofounded Clergy and Laity Concerned About Vietnam with Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel and Father Daniel Berrigan. A Eugene McCarthy delegate to the 1968 Democratic National Convention, he was arrested in the tumult of that infamous event.

How did the radical Neuhaus of the 1960s become the conservative icon of the 1990s and beyond? While there were important breaks along the way, Neuhaus never conceded any major upheaval in his own thinking. Rather, he argued, the rise of a militant secularism among cultural elite, and the evacuation of religious belief from public life and civic debate, had conspired to create a “naked public square,” the title of his 1984 bestseller.

While never accepting the premise of a “Christian America,” Neuhaus argued that the constitutional separation of church and state was meant to protect private practice but also enhance—not prohibit—the “free exercise” of religion in public life. The gravest moral and legal issues in American history, he maintained, from slavery to abortion, required the kind of conscientious engagement sanctioned by the church’s understanding of itself as a community of witness. Moreover, our most cherished political principles—including the irreducible value of persons, free speech and religious liberty, resistance to tyranny, and respect for the rule of law—are all grounded in religiously informed beliefs. He came to see that the “moratorium on God” pushed by the secular Left would undermine, and eventually destroy, the American experiment in democracy. At the same time, Neuhaus believed in a public church, not a partisan church. As Abraham Lincoln often said, the question is not whether God is on our side, but whether we are on his.

In 2005, Time magazine included Neuhaus in its list of America’s 25 most influential evangelicals. By that time, Neuhaus had become a confidant and adviser to President George W. Bush, and was widely recognized as one of the most respected conservative voices in the country. This year, 2009, marks the 25th anniversary of The Naked Public Square. Though it has become a classic, it still remains a kind of manifesto for evangelical engagement with culture. Without Neuhaus and the movement that coalesced around him, it would be difficult to explain the activism of Chuck Colson and Rick Warren, the journalism of Michael Gerson, the networking of Michael Cromartie, the advocacy of James Dobson, or the social ethics of Richard Mouw (whose connection to Neuhaus goes back to “the Hartford Appeal” of 1975).

I first came to know Neuhaus in the early 1990s, when he and Colson gathered a team of theologians to form the project known as Evangelicals and Catholics Together. Just as Neuhaus never considered his transition from radicalism to conservatism to be anything more than the outworking of basic principles of human rights, civil liberty, and moral concern, so, too, did he not consider his embrace of Catholicism a major leap in his journey of faith. He once wrote an essay titled “How I Became the Catholic I Was” (First Things, April 2002).

Reformation Catholic

Though Richard would not like my putting it this way, he could just as well have written an essay on “How I Remain the Lutheran I Used to Be.” I do not mean to question his devotion to the Catholic Church and the Pope, a devotion that was unbounded. But only a thinker so well grounded in the Reformation traditions could be an honest broker in bringing faithful evangelicals and believing Catholics to recognize the common source of their life together in Jesus Christ, the Holy Scriptures, and the great tradition of living faith through the centuries.

Some years ago, Richard had a serious bout with cancer and nearly died. Out of this experience, he wrote what may be his most enduring book, As I Lay Dying, a little masterpiece of great spiritual power. “We are born to die,” he wrote. “Not that death is the purpose of our being born, but we are born towards death, and in each of our lives the work of dying is already underway. The work of dying well is, in largest part, the work of living well.” Richard John Neuhaus lived well, and toward eternity, and he was laid to rest in the sure and certain hope of the Resurrection.

Timothy George is the founding dean of Beeson Divinity School of Samford University and a senior editor for

Christianity Today

.Copyright © 2009 Christianity Today. Click for reprint information.

Related Elsewhere:

Christianity Today published a liveblog post and news article that compiled reactions from others on Neuhaus’ death.

Previous CT articles on and by Neuhaus include:

A Voice in the Relativistic Wilderness | The Pope crusaded for “moral truth.” We should welcome his help. (April 4, 2005)

A Modest Step Toward Unity | Richard John Neuhaus on the Catholic bishops’ decision to join Christian Churches Together. (November 11, 2004)

Books: Inside the Vatican | The pope’s chief doctrinal officer has always been in dialogue with the Reformation traditions. Now he reveals his vision for Christianity in the new millennium. (May 18, 1998)