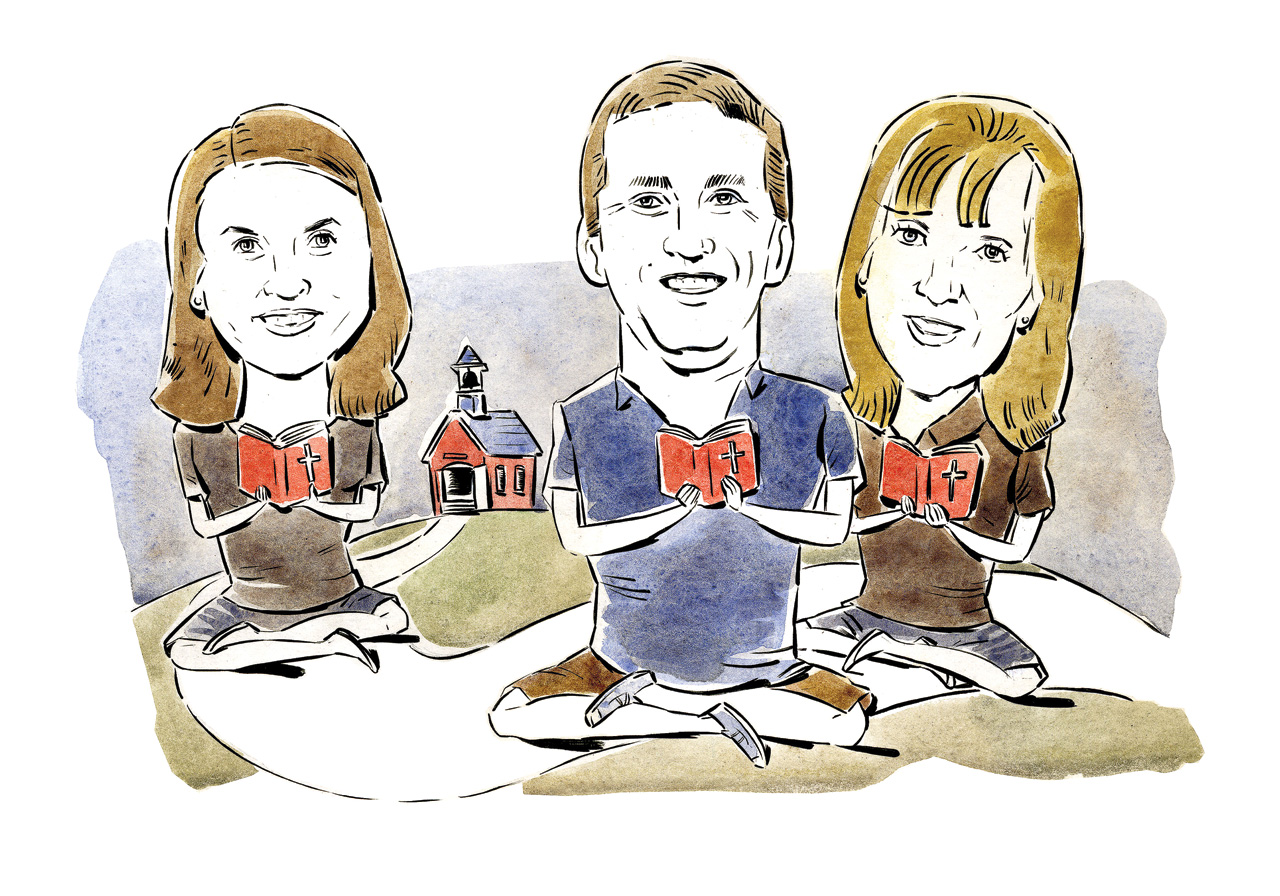

Earlier this summer, a California judge ruled that Encinitas Union School District's yoga program can continue because it is not religious in nature. The sponsors of the yoga program want to roll it out to other public school districts. Should schools allow it? We asked three Christians who have written on yoga and Christian views of the body to weigh in.

Set Limits, Not a Ban

Amy Julia Becker blogs for Her.meneutics and is the author of several books, including Why I Am Both Spiritual and Religious.

My children began to learn yoga through our local public preschool a few years ago. They came home eager to show me "butterfly," "snake," and "dog" poses. At the school's Mother's Day celebration, they showed off their skills with a mixture of stretches, creative movement, and feeble attempts to sit still and breathe calmly.

Although I attended a regular yoga class myself, I was somewhat concerned that my children were learning yoga in school. I knew about its Buddhist and Hindu roots. I didn't want my kids to be indoctrinated. And it felt almost like an affront that they might be taught yoga in school, but wouldn't learn about Christmas or Easter there.

Once I thought it through, I realized that my kids were benefitting from the same aspects of yoga I experienced in my local studio. My kids weren't being asked to raise their hands in prayer or to chant, "Om." There were no statues of the Buddha. Rather, they were learning strength, balance, and flexibility. They were learning how to quiet their minds and bodies. They were learning that physical challenges can happen beyond the athletic fields and competition.

Yoga in public schools is appropriate as long as it is practiced within parameters that separate church and state. As far as I can see, two possibilities exist. One follows the model of my children's school. If yoga is a school-wide aspect of physical education or other classes, then it should be permitted only within proper and appropriate boundaries.

Yoga can be practiced in a purely physical manner as a way to provide students access to strength training, flexibility, and balance, as it was for my children. But just as a physical-education teacher shouldn't quote the apostle Paul before asking students to run a lap, the spiritual aspects of yoga have no place in a public school.

But yoga could also be practiced, even in a spiritual way, if done through a student-initiated voluntary group. Although public schools need to protect the separation of religion and state when it comes to any mandatory activity or curriculum, schools also should allow students freedom of religious expression.

Just as student-initiated Christian prayer groups should be allowed on public school campuses, voluntary student-sponsored yoga that draws on Buddhist or Hindu practices should likewise be permitted.

If my kids continue practicing yoga, inside or outside school, I will teach them that yoga has its roots in a spiritual tradition. And I will teach them that the Christian tradition also seeks to connect the mind, body, and spirit. I will explain to them how yoga has become one way for the Holy Spirit to work in me to begin to integrate these parts of my being. And I will be grateful that they learned the physical benefits of yoga at a very young age.

Context Is Everything

Matthew Lee Anderson is author of Earthen Vessels: Why Our Bodies Matter to Our Faith and lead writer at MereOrthodoxy.com.

Should yoga be banned from public schools? The answer is short and complicated: It depends. Whether yoga should be banned in public schools depends entirely upon the range of activities we include beneath the umbrella terms at stake, namely yoga and religious activity.

To see how contested the meaning of yoga is, try telling any Christian who practices yoga that it can't be extracted from its ostensibly Hindu roots. They will likely point to the physical benefits of posture, breathing, and so on, while denying that there has to be any spiritual content to it.

Then go tell a Hindu apologist that, in fact, yoga has roots in early-20th-century British "physical culture" and was an Indian reaction to the YMCA's attempt to Christianize India through importing Swedish stretching (as Mark Singleton argues in his excellent book, Yoga Body). They will not like that story much.

The fact is, though, that whether yoga is a religious practice has a good deal to do with who is leading the particular event and what it involves. Some people approach it as an aggressive form of calisthenics. If that is the context, there is no reason to ban it from schools. In that case, in fact, such an exercise wouldn't qualify as a religious practice at all. There would be good reason to drop the term yoga altogether and perhaps replace it with a new label, to make the point clear.

But others are intent on keeping the physical exercise tied to its alleged Hindu roots. In such a case, incorporating yoga into the schools should be subject to standard rules regulating religious activities in public schools.

I should note, though, that I'm not arguing for incorporating yoga simply by changing the name. To treat these two forms as identical, we would have to argue that there is something inherent in the particular poses and forms that draws people away from knowing the real God.

That sort of argument could have merit—I see no viable possibility, for instance, that Christians should ever take up "pole dancing" as a meaningful athletic activity. Pole dancing is clearly and inherently tied to objectifying and sexualizing women and is an activity Christians should avoid. But given yoga's similarity to other, Western, purely athletic forms of exercise, decrying the poses and contortions that in part make it up is considerably harder.

It's Disguised Hinduism

Laurette Willis is a Christian fitness expert and founder of PraiseMoves, a Christian alternative to yoga (PraiseMoves.com).

If religious activities like Christian, Muslim, and Jewish prayers are banned from public schools, then yoga should also be banned.

"But yoga is just exercise!" many exclaim. Hindus, however, view yoga as part of their religion. Professor Subhas Tiwari of the Hindu University of America acknowledges that yoga originated in Hindu Vedic culture. He says it is impossible to separate yoga as a physical practice from yoga as a spiritual practice.

I consider yoga a missionary arm of Hinduism and the New Age movement. I was involved in yoga and the New Age movement for 22 years, from age 7 to 29. I know firsthand that yoga offers much more than physical exercise. Before I became a Christian, I was a student of Hatha Yoga and Kundalini Yoga and an instructor of Hatha Yoga, as was my mother.

My mother and I became involved in yoga through a daily television program. She found that the exercises relieved her stress. She became a yoga instructor, and I followed in her footsteps. Little by little, we began to favor visiting the ashram in upstate New York over church activities. As we became more involved, it also opened the door to numerous other New Age interests and practices.

Yoga postures represent offerings to millions of Hindu gods. In fact, there is a dedicated "Lord of Yoga." His name is Shiva, a supreme divinity. Yoga in Sanskrit means yoke or union, and famous yogis teach that "yoga unites the individual self to the universal self." Thus, yoga practitioners are, however unintentionally, attempting to unite themselves to Hindu divinity.

This is antithetical to the Christian faith. We are told to "abstain from things offered to idols" (Acts 15:29, nkjv). Jesus tells us to take his yoke upon us and follow him to find rest, "for my yoke is easy and my burden is light" (Matt. 11:30).

But surely a public school's yoga class would be completely devoid of all religious aspects. Some promise this. But years later, when your child as an adult is visiting a bookstore and passes by the Eastern religion section and sees books on yoga, he or she may very well equate it with the warm fuzzies felt during those supposedly religion-free yoga sessions in third grade.

One option for schools is to use our PowerMoves Kids curriculum. It focuses on character education and fitness, not religion.

Christians realize there is a spiritual realm we cannot see. Paul warned that "we do not wrestle against flesh and blood, but against principalities, against powers, against the rulers of the darkness of this age, against spiritual hosts of wickedness in the heavenly places" (Eph. 6:12, NKJV). These spiritual forces have power, and they do influence us. They have a way of subtly and deceptively pulling us away from the one true God, our Lord Jesus Christ.