What's the nature of human consciousness? What if, instead of determining our actions for ourselves, we merely feel like we decide what to do? If the U.S. has the power to micromanage the affairs of other nations, should it? Do the rights of the individual continue even if he's like four-fifths robotic?

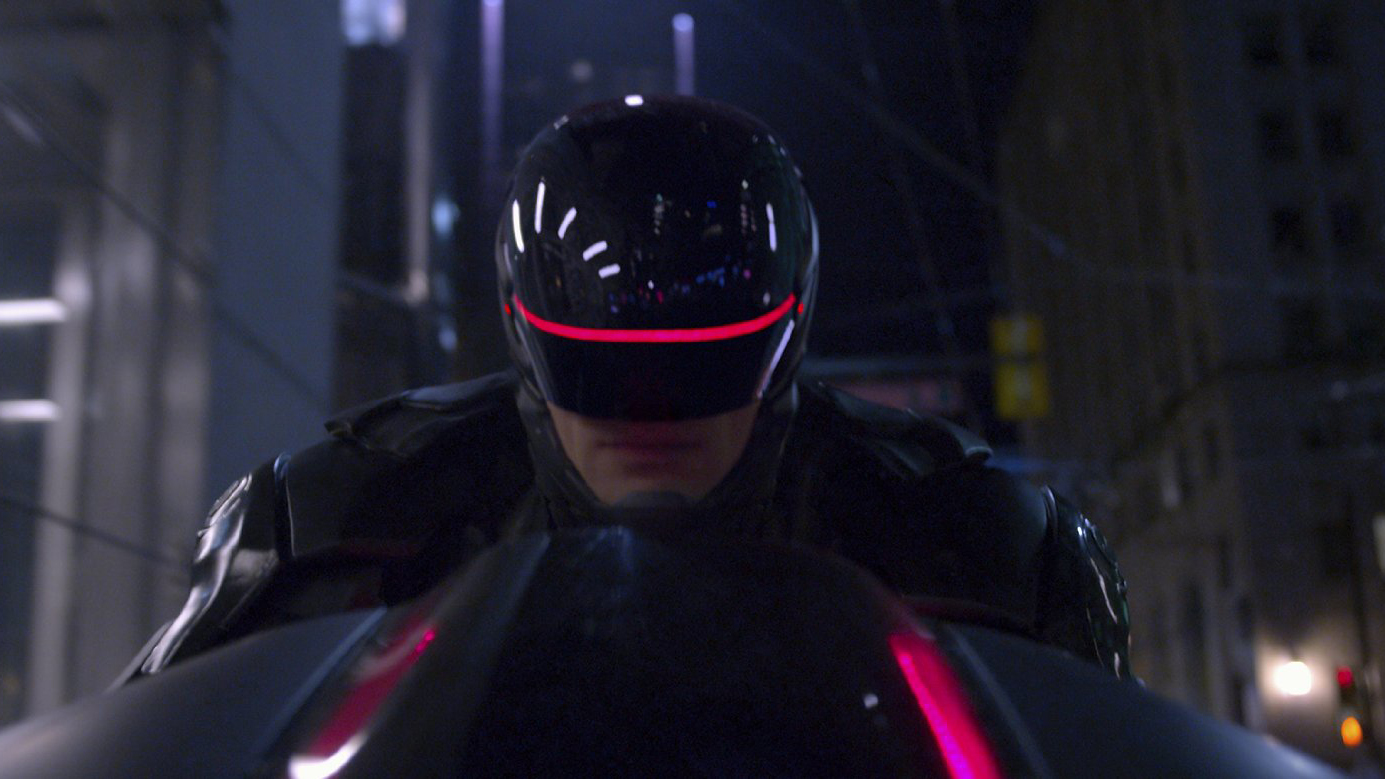

All these questions and more fail to be answered—but are at least entertainingly presented—in Jose Padilha's remake of RoboCop. A remake of the 1987 Paul Verhoeven film, this time around the movie stars Joel Kinnaman as Alex Murphy, Mr. Robocop himself.

Kerry Hayes / Columbia Pictures

Kerry Hayes / Columbia PicturesMurphy and his partner Jack, played by Michael K. Williams, are maybe the only cops in the Detroit precinct who aren't on a criminal's payroll—a problem just as present in the film's 2028 setting as in 2014. But Murphy's determination to bring down a local crime boss leads him to be the target of an explosive attack, one that blows off a bunch of his limbs and burns his skin off and stuff (the movie alleges "fourth degree burns," which a quick Google search confirms are a real thing).

At the same time, OmniCorp CEO Raymond Sellars (played by Michael Keaton, who dresses about twenty years too young for the role) is facing roadblocks in Congress that'll prevent him from getting robots on the street to replace cops—and for Sellars, robots on the street means billions in his pockets. So Sellars and his OmniCorp buddies concoct a plan to merge the human and robot elements, thus circumventing the congressional ban on purely robotic police officers. Murphy is picked for the program, and the rest is history—well, 1989's 2028 history.

The good thing about RoboCop is that it totally exceeded my expectations while I was watching it. It's actually a pretty rigorously engaging movie-watching experience. It's interesting and exciting without relying on too many plot clichés (though storytelling clichés abound). For instance, at no point does the film feel like a re-hash of 2008's Iron Man, despite how many notes Iron Man took from the 1989 RoboCop.

So the movie isn't predictable—a striking contrast with 2013's deeply mediocre remake of Total Recall, which took the original movie and recast it in the mold of a boring old Modern Action Thriller. It spends considerable time developing the relationship between Murphy and his family, as well as chronicling his own psychological distress; for the first third of the movie, I was incredulously hopeful that this could be good, personal, introspective sci-fi in the same way District 9 was.

But right around the middle third of the movie, disaster strikes, not with a bang but a whimper. RoboCop is a deeply confused movie, in which are embedded the seeds of maybe three of four much better movies. On the one hand, the opening fifteen minutes of the film show off a dystopian-like world in which modern U.S. drone protocol has been extended to combat robots on the ground with fingerprint scanning technology, all in the interest of "keeping the peace"—the kind of moving, searing critique Verhoeven embedded into RoboCop and Starship Troopers.

Kerry Hayes / Columbia Pictures

Kerry Hayes / Columbia PicturesBut then Samuel L. Jackson keeps showing up as a Hannityesque talk news anchor, arguing passionately in favor of OmniCorp's policies, a filmmaking choice totally in line with Verhoeven. Since the ground-level story of Alex and his family is very sweet—almost schmaltzy—this results in dissonance between the movie's micro-level (the earnest sincerity of Alex Murphy) and the macro-level (the cynicism of Jackson's character).

On the grand scale, Jackson's talk-show interjections only work as satire if they're more than just over-the-top depictions of what already exists. Sure, the character is just an overblown version of contemporary megapartisan television hosts. But what is the movie trying to say via these digressions? Jackson is both the first and final character we see on screen. He never interacts with Murphy or almost any of the main cast. So what's he doing here?

I only ask because the intense and maybe excessive use of irony in Jackson's segments—"Spoken like a true patriot," Jackson says at one point, and it's assumed that the audience would scoff at this. He closes the film with "America has always been, and will always continue to be, the greatest nation on earth," again, as if the audience would know to laugh at these segments. Are they just there to instill a deep sense of cynicism and irreverence in the audience?

It's so weird, because Murphy's segments are saccharine. But I was willing to accept it—all the movie's questionable neuroscience and tin-eared dialogue—"Something's causing problems in the system, but it's not just chemistry or brain signals." "What, like, a soul?"—for the same reason I was when I reviewed Thor 2 a few months ago. I really like movies that just are what they are, even if sometimes what they are is stupid. It's really not the worst thing in the world for a movie to be stupid.

However, RoboCop doesn't want its audience to think critically about how dumb-but-nicely-sweet the sentimental parts of the movie are, but then turns right back around with its possibly aimless critiques of—of what, America as a whole? Capitalism? The modern media?

In trying to have its cliché cake and eat it too, trying to be sentimental and cynical all at once, RoboCop does neither thing well.

Kerry Hayes / Columbia Pictures

Kerry Hayes / Columbia PicturesIt's not really as malignant as I make it out to be. These problems just add to the incoherence of a pretty confused movie. RoboCop overextends its reach, trying to touch on (deep breath): American foreign policy, suicide bombers, Tehran, capitalism, police corruption, individual psychological distress, family problems, all-out action sequences, epiphenomenalism, and androdigital interaction. (Note that Martin Scorsese has, in his entire career, successfully approached only five out of the above ten issues.)

So what we're left with is a movie that's actually pretty fun to watch, if you're into that kind of thing, but which falls apart within minutes of you leaving the theater. Why did they structure the plot that way? What was the point of those TV sequences? What is this movie about?

All movies fall apart under enough critical scrutiny, even genius ones. But when your film crumbles after just being grazed by critical thinking, then you've got a problem.

Some movies are genera-transcendingly good—for instance, The Lego Movie is incredible even if you don't particularly love kid's movies, and The Kings of Summer (reviewed alongside Man of Steel) is excellent even if you don't normally like coming-of-age stories (I know I don't).

And then some movies are just good at what they are—like the aforementioned Thor 2, which, as I said in my review: if you're cool with a movie that begins with an extended dissertation on "Night Elves," then you'll love it, and if you're not, then you'll think it's very dumb.

Well, there's no getting around the fact that, no matter what kind of movie you like, RoboCop is pretty dumb. It's also kind of exciting, and gripping, and makes for a pretty good movie-watching experience—especially on the big screen, especially if you want to like it. But by no means is this movie for everyone. In fact, it might not even be for the kinds of people who are trying to like it.

Caveat Spectator

RoboCop is rated PG-13 for violence and language, and true to form, there is both violence and language, though neither very intense nor extreme. A lone f-word peppers the script, but it's used in a comedic (rather than insulting or demeaning) context—as well as some bleeped swear words on Jackson's show, accompanying about a dozen un-bleeped s-words and maybe two-dozen little-league profanities. Murphy and his wife start to get intimate before they're interrupted—Mrs. Murphy is seen from behind in only her pants and a bra. It's pretty tame.

We see some extended shots of Alex Murphy's burnt body, but it's less disturbing than what was featured in Star Wars Episode III. In one kind of gross scene, Alex's robotic parts are removed to impress upon him the gravity of his situation; his esophagus is exposed, all that's left of him being a lone hand and his exposed upper thoracic region—we see his lungs pumping and hear his heartbeat. It's icky.

Jackson Cuidon is a writer in New York City. You can follow him on his semi-annually updated Twitter account: @jxscott.