Update (Feb. 10): Here's what Wheaton, Hawkins, and others said at their public reconciliation attempt.

—–

Two weeks ago, faculty leaders unanimously asked Wheaton College to drop its attempt to fire tenured professor Larycia Hawkins over whether her views on Islam fit the school's faith statement.

On Friday, 78 of the Illinois school’s 200-plus professors publicly vouched for the orthodoxy of Hawkins's theology and requested the same.

On Saturday, provost Stanton Jones told faculty that he had revoked his recommendation that started the termination process.

Hours later, the college and Hawkins jointly announced “a confidential agreement under which [we] will part ways.”

”[We] have come together and found a mutual place of resolution and reconciliation,” the two sides stated in a press release complimenting each other and stating they "wish the best for each other in their ongoing work."

In a Saturday evening email, Jones informed faculty that earlier in the week he had “communicated to Dr. Hawkins that I recognize her as a sister in Christ, and that it was never my intent to call the sincerity of her faith into question.

"I asked Dr. Hawkins for her forgiveness for the ways I contributed to the fracture of our relationship, and to the fracture of Dr. Hawkins’ relationship with the College," wrote the provost. "While I acted to exercise my position of oversight of the faculty within the bounds of Wheaton College employment policies and procedures, I apologized for my lack of wisdom and collegiality as I initially approached Dr. Hawkins, and for imposing an administrative leave more precipitously than was necessary.”

Jones says he also regretted not explaining the college’s public response, and for “introducing significant confusion regarding possible options for resolution.”

“I stand by my concerns that Dr. Hawkins’s theological statements raised important questions," he wrote. "However, in light of the deficiencies in my early responses, and recognizing that Dr. Hawkins’s Theological Response was a promising start toward answering satisfactorily some of the questions that I was raising at the time, I revoked the Notice … and turned resolution of the administrative leave over to President [Philip] Ryken.”*

That email was followed by an email from Ryken to students, faculty, and staff announcing the decision to part ways. The decision, Ryken said, came after Jones’s apology and withdrawal of the notice of termination.

“This is a time for prayer, lament, repentance, forgiveness, and reconciliation,” Ryken said, beginning with a private reconciliation service for faculty, staff, and students to be held Tuesday evening.

The president also noted: “Because concerns have been raised about many aspects of this complex situation—including concerns related to academic freedom, due process, the leaking of confidential information, possible violations of faculty governance, and gender and racial discrimination—I have asked the Board of Trustees to conduct a thorough review. One of the main purposes of this review will be to improve the way the College addresses faculty personnel issues in the future, especially when these issues relate to our Statement of Faith.”

Ryken concluded, "Over the last two months we have experienced an unprecedented outpouring of prayer from the wider Wheaton community and indeed from the worldwide church. This makes me hopeful that God is working out his good purposes, perhaps in unexpected ways, and that Wheaton College may ultimately be strengthened through this time of suffering."

The weekend announcements came shortly after about one-third of Wheaton’s full-time faculty jointly defended Hawkins’s theology and a leaked memo revealed discrimination concerns. Meanwhile, some students and alumni had embarked on a hunger fast until after the scheduled February 11 hearing, for the purpose of "lament, reconciliation, and shalom."

On Friday, almost 80 current faculty members asked Wheaton to drop its attempt to fire Hawkins and restore her to the classroom instead.

“We have carefully examined the written theological statement that Professor Larycia Hawkins submitted to the Wheaton College administration on December 17, 2015,” stated 78 professors in a group letter published by The Wheaton Record. “Our judgment is that Professor Hawkins has not failed to affirm or model the Wheaton College Statement of Faith or Community Covenant."

Some posed with signs supporting their colleague. Alumni expressed mixed reactions in the comments section of the student newspaper's exclusive post.

On Friday, the Record also published an interview with Hawkins (conducted on January 30) in which she explained, among other topics, her vision of a win-win scenario: reconciliation between herself and the college.

"It’s not overspiritualizing—win-win to me is that the world knows that we are Christians by our love. We would bless one another," Hawkins told the student newspaper. "Like I’ve said from the beginning, I will bless Wheaton College, I will not curse it. This isn’t me vs. Wheaton. What the world needs to know is that we’re Christians by our love, and that’s win-win for me."

According to Saturday's joint statement, the hoped-for reconciliation was achieved, but it will not result in the associate professor of political science remaining at the college after nine years of service. Wheaton and Hawkins will not share more information until a press conference on Wednesday, February 10, "in pursuit of further public reconciliation."

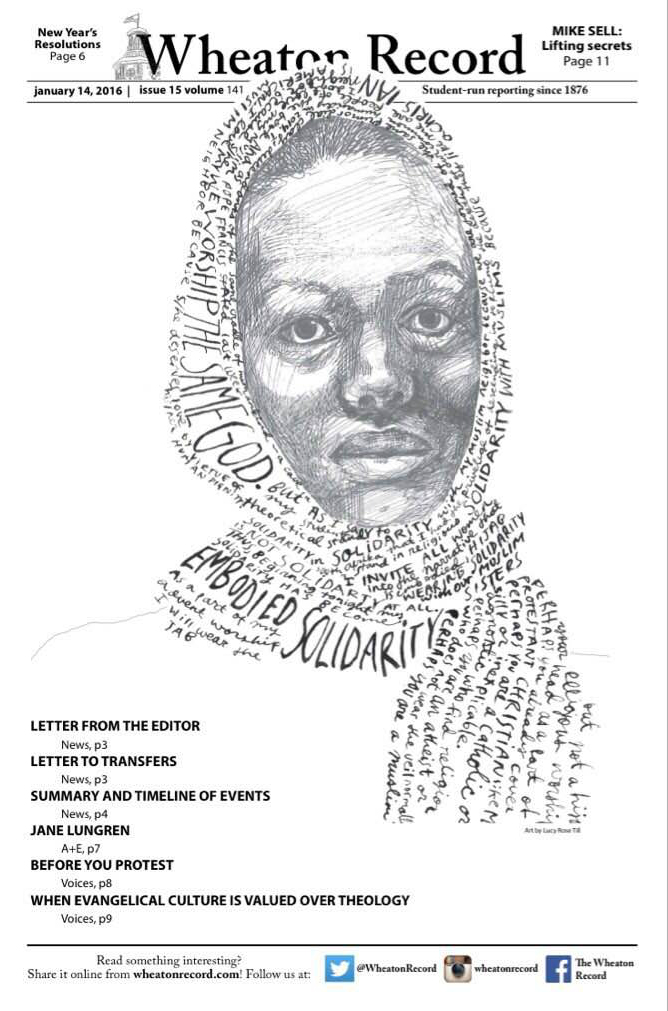

Hawkins had recently told CT that "for the sake of my students and colleagues, I continue to seek reconciliation with Wheaton College." Last month, she asked that her supporters pray for Jones specifically, as well as for the college at large. “Embodied Solidarity is not demonizing others in defense of me,” she said.

Hawkins recently explained to Sojourners why she wanted to stay at Wheaton, as well as why she has no regrets over the December act that precipitated her theological scrutiny: wearing a hijab during Advent as an expression of "embodied solidarity" with Muslim Americans in the wake of prominent figures such as Donald Trump and Franklin Graham calling for bans on Muslim immigration to the United States.

White evangelicals are divided on whether there is “a lot” of discrimination against Muslims in the US (44% say yes, 49% say no), but 75 percent do think discrimination against Muslims in the US is increasing, according to a new study by the Pew Research Center. Among black Protestants (two-thirds of whom identify as evangelicals), 68 percent say there is a lot of discrimination, and 75 percent say it is increasing.

When asked if they personally know a Muslim, 43 percent of white evangelicals and 58 percent of black Protestants said yes, while 56 percent of white evangelicals and 42 percent of black Protestants said no.

Hawkins's Advent activism drew the ire of Graham (in sum: "Shame on her!"), who has also been "surprised and disappointed" by her defenders at Wheaton. "How the faculty council can now support this professor being allowed to teach students is deeply concerning," he wrote on Facebook and Twitter last month.

In the wake of its December decision to place Hawkins on administrative leave, Wheaton explained that its concern was "in no way related to her race, gender or commitment to wear a hijab during Advent," but instead was related to her explanation of the act which "seemed inconsistent with Wheaton College’s doctrinal convictions."

The explanation in question: “I stand in religious solidarity with Muslims because they, like me, a Christian, are people of the book,” Hawkins wrote on Facebook on December 10. “And as Pope Francis stated last week, we worship the same God.” She invoked Yale theologian Miroslav Volf (among others) in her defense, and later explained her full theological stance to the college.

On Monday, Hawkins donned the headscarf again for World Hijab Day, tweeting, "I'm veiled today and I'm in good company with Muslim & non-Muslim sisters."

On Tuesday, a group of 20 Wheaton alumni who are now political scientists wrote an open letter to Wheaton's president and trustees "in hope of encouraging reconciliation." They expressed concern that the standoff was harming Wheaton's ability to attract "first-rate professors" as well as the ability of graduates to enter academia themselves.

On Thursday, Time magazine revealed that Wheaton's faculty diversity committee recently concluded that "the college has demonstrated a pattern of differential over-scrutiny about Dr. Hawkins’s beliefs in ways often tied to race, gender, and marital status." Hawkins is the college's first black, female professor to receive tenure.

"As a female and minority professor, I know that my views have been solicited by the administration in its quest for greater diversity," Hawkins told CT in response. "As an underrepresented voice at Wheaton, I’m asked to speak into a lot of different situations on a lot of different kinds of topics, and I do that willingly. I welcome those queries, and I see that as part of my institutional service. What that does is it puts me in the position of being a lightning rod on campus surrounding the most controversial issues.

"Much of the time, the administration is asking me to speak into these issues. I grew up in the black church tradition, and in the black church tradition, we talk about speaking truth to power in a prophetic voice. Power doesn’t always want to hear the things we have to say," she continued. "As someone who’s an outsider to evangelical institutions—I didn’t go to a Christian college, I went to Rice University—I think that sometimes the outside voices at Wheaton College are seen as too shrill or a clanging gong as opposed to being said in love."

CT previously noted what evangelical experts on missions and Muslims think of the "same God" debate, as well as the views of Arab evangelical leaders and Wheaton's provost.

CT also editorialized on how Wheaton and Hawkins should reason together.

The relationship between Islam and Christianity—and whether they worship the same God—has caused Wheaton headaches in the past. In 2008, former president Duane Litfin signed a Christian response letter to "A Common Word between Us and You," a statement from 138 Muslim scholars and clerics calling for interfaith cooperation. Jones, Wheaton’s provost, also signed the document. Both later dropped their endorsements.

The debate over whether Christians and Muslims worship the same God is a perennial one. The question topped CT's most-read stories of 2002 and top questions of 2014.

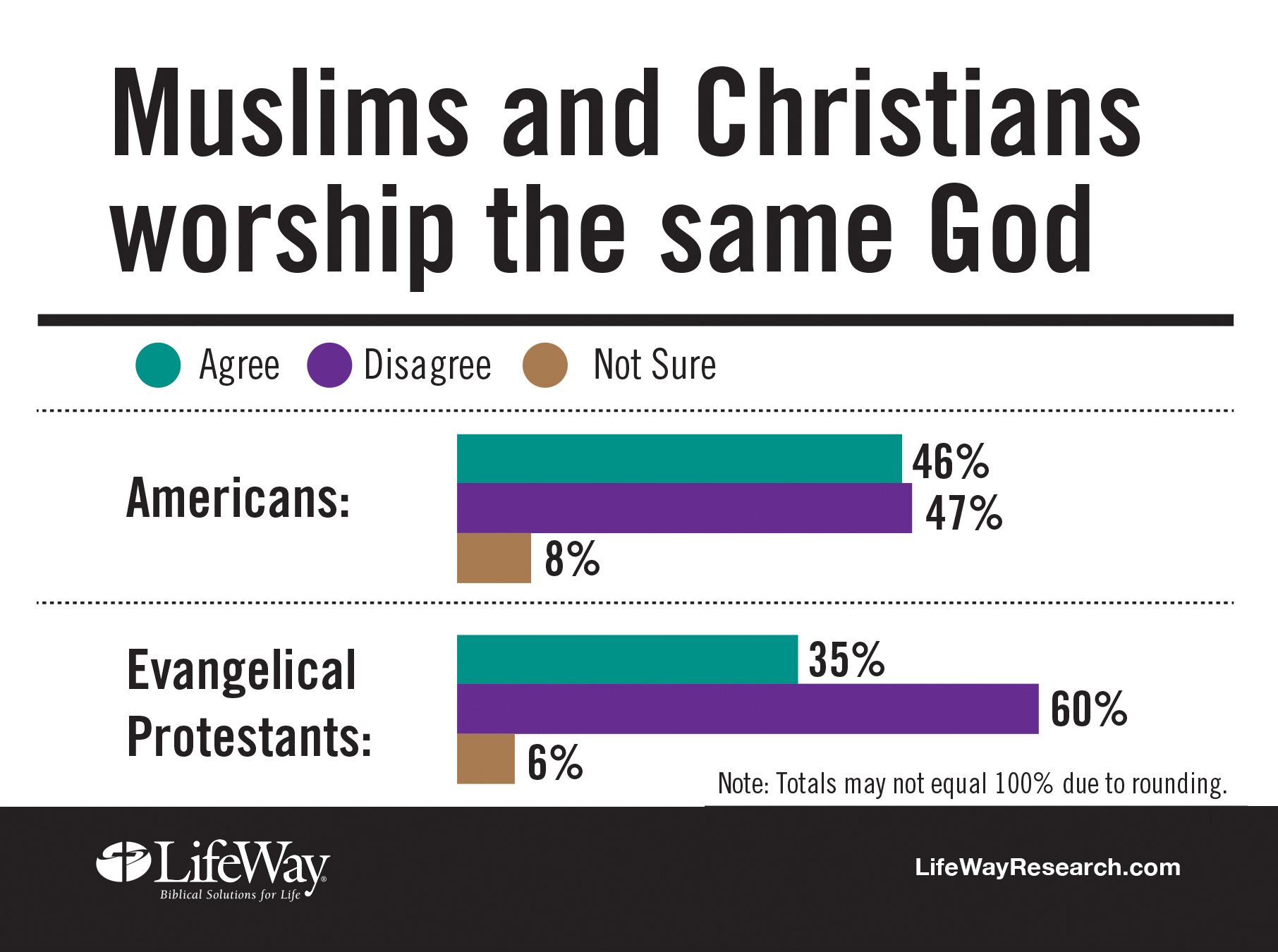

The larger evangelical community is divided. About 35 percent of evangelical Protestants believe that Muslims and Christians worship the same God, according to a recent LifeWay Research survey, while a majority of 60 percent disagree. Americans overall are evenly split: 46 percent believe that Muslims and Christians worship the same God, while 47 percent disagree.

Baptist theologian Timothy George considered the question in a 2002 CT cover story. In 2008, CT looked at whether shared monotheism is the best starting place for Muslim-Christian dialogue.

A Chicago Tribune editorial earlier praised both Hawkins and Wheaton for showing "remarkable tolerance" during the dispute. “Unravel this situation, which has left Hawkins suspended, and you find more expressions of tolerance than most disputes rooted in religious pluralism include,” wrote the paper. “If every disagreement in higher education had stakes this important and voices this thoughtful, then every college diploma would be worth even more than it is.”

[Hawkins cover drawing courtesy of The Wheaton Record ]

*Correction: An earlier headline on this article inaccurately said that Hawkins had been reinstated.

[Post updated on Monday, February 8, with joint faculty letter, Record interview, fuller Ryken statement, and minor edits for clarity.]