In this regular series, we share innovative practices from the world of stock photo ministry.

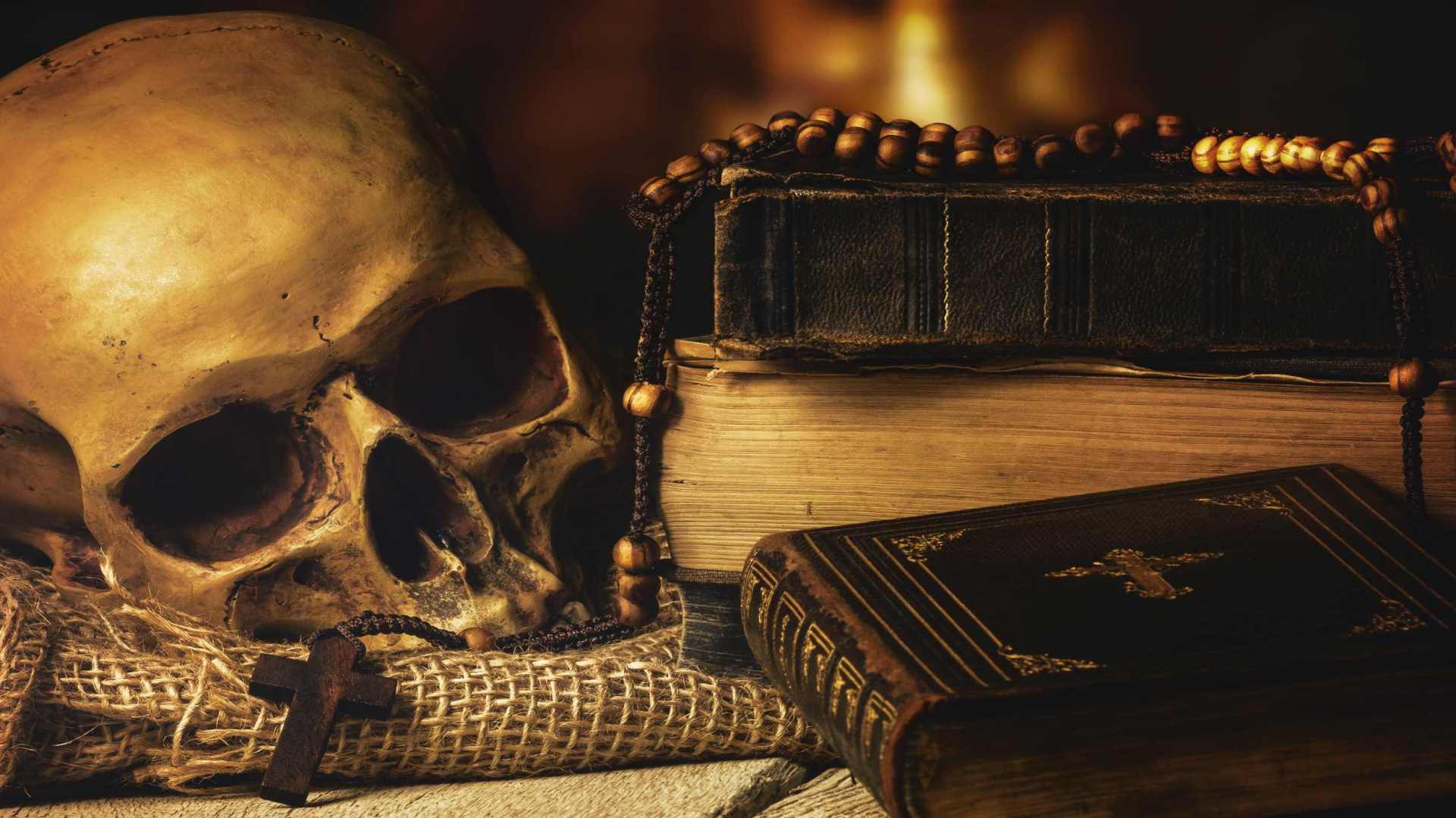

The thing about a truly great awkward stock photo is that, if it’s framed and lit well enough, you won’t even notice how little sense it makes—at least not for a while. When you first glance at this week’s image, for instance, you might simply think, “Hmm, that’s cozy and/or terrifying.” But if you look at it a bit longer, you’ll start to feel that something is deeply, darkly amiss.

A human skull, some rosary beads, a burlap sack, a Bible, another Bible (extra credit!), all casually sitting in front of a crackling fire—have we stumbled into the lair of a Zorro villain? Are we trying to conjure a curse on the local parish priest? Maybe we’re just cleaning out Rick Santorum’s attic? Who knows? (Probably not poor Yorick there.)

Of course, there have been generations of Christians for whom the juxtaposition of the skull and the Bible wouldn’t have been so strange. Many generations have lived when following Jesus could literally get you killed, and in times of persecution, the early church was rumored to have worshiped secretly in the catacombs, surrounded by decaying flesh. This macabre legacy can still be seen throughout Europe, where numerous churches, chapels, and shrines are decorated with the bones of the saints.

This décor, while unusual outside of the Hot Topic set, was easy to accomplish, considering the medieval church was basically drowning in dead bodies it didn’t know what to do with. For most of their history, Christians regarded cremation as essentially pagan, if not outright sinful—deliberate destruction of a body that God had created good, redeemed, and promised to resurrect. Burying the dead had been the practice of believers, and so it was what Christians did as well.

That seemed like a great idea—until vast swaths of the world began converting to Christianity, and then dying, and the cemeteries started literally overflowing.

It was kind of gross.

But not that gross. As Christians knew, death had been conquered and the body made holy along with the soul. The corpses erupting from the ground weren’t gross; they were holy. And as the Bible says, when you have something holy, you’re required to use it as a part of your decorating scheme. (That’s somewhere in there, right?)

And so, we ended up with bone-themed churches, chapels, and shrines dotting Europe—places like the Sedlec Ossuary in Czechia, which features a chandelier and a coat of arms constructed entirely from human bones, and the Capela dos Ossos in Portugal, which (in addition to walls bricked with skulls) features two complete dried corpses hanging near the altar, and whose transom reads, “We bones are here, waiting for yours.” It’s the perfect antidote to that overly-cheery CCM. (Modern America may have its heavy metal churches, but as we all know, Europe was metal before even metal was metal.)

Such churches are instructive not only to those of us looking for fun altar-decorating tips, but also to those of us pondering the nature of existence, worship, and even the church itself. One lesson here is obvious: that none of us are ever terribly far from the land of the dead.

But there’s also a second, more subtle lesson to be learned: that the dead aren’t far from us, either. They still live, worshiping day and night before the throne, and waiting for the day the risen God will cause flesh to grow once more on their dry bones.

And when that happens, we can finally ask them what it’s like to taste mortar for thousands of years, I guess.