Few events in modern history illustrated the corrosive impact of abortion culture like the Kermit Gosnell case of 2013. Gosnell ran the Women’s Medical Society Clinic in West Philadelphia and was convicted of a myriad of state and federal criminal charges, including first-degree murder of infants (delivered alive and then killed with scissors), involuntary manslaughter (a Nepalese refugee mother died in his clinic while undergoing an abortion in 2009), and numerous drug trafficking charges.

I once stood on the sidewalk in front of Gosnell’s clinic. From the outside, it looked like any “good Samaritan" community health center. Inside, however, it was a house of horrors. If you’ve read the official law enforcement reports or watched the chilling documentary 3801 Lancaster: American Tragedy, you know this description is not hyperbole.

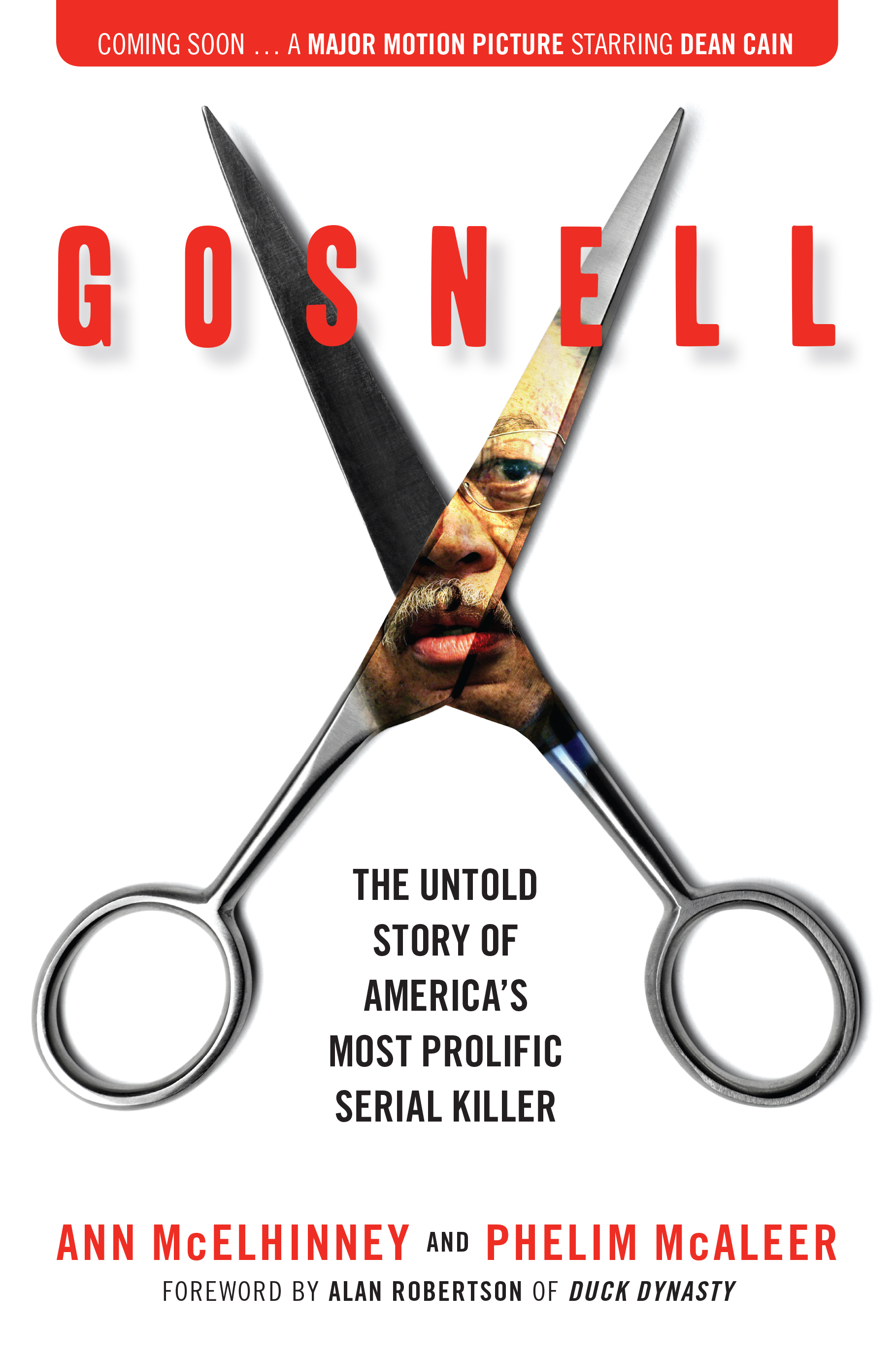

With the release of the Lancaster film, as well as Gosnell: The Untold Story of America's Most Prolific Serial Killer by Ann McElhinney and Phelim McAleer, the Gosnell case is back in the spotlight with everything it offered us the first time: a sobering reminder of the criminal aspects of the abortion industry and a reason to reinvigorate the pro-life movement.

The Gosnell story received national (albeit delayed) media attention in part because the crimes and atrocities committed at the Women’s Medical Society Clinic were described in detail throughout the course of the trial. The allegations against Gosnell could not be dismissed as unreliable hype from the biased anti-abortion crowd. No reasonable person—pro-life or pro-choice—could read the grand jury report and not feel ill and outraged.

“Gosnell’s contempt for the law and his patients cost Karnamaya Mongar [the Nepalese refugee mother] her life,” the grand jury reported. “Her death was the direct result of deliberate and dangerous conduct by Gosnell and his staff. They consciously disregarded the unjustifiable risk that their conduct would cause death.”

USA Today columnist Kirsten Powers covered the Gosnell case in depth and described two key reactions. The first was revulsion over the murderous horrors enacted upon women and children at the clinic, and the second was incredulity over the lack of any national news coverage of the story. “You don’t have to oppose abortion rights to find late-term abortion abhorrent or to find the Gosnell trial eminently newsworthy,” Powers wrote. “This is not about being ‘pro-choice’ or ‘pro-life.’ It’s about basic human rights. The deafening silence of too much of the media, once a force for justice in America, is a disgrace.”

Once the story gained traction—thanks in no small part to Powers’ investigative journalism— mainstream news outlets did something shocking: They not only covered the trial in detail but also began asking why Gosnell’s crimes had been ignored to that point. It was unlike anything I’ve seen before or since. Journalists asked substantive questions about late-term abortion and clinic regulations. New, transparent discussions—about abortion as public policy, and as a public health matter for women and babies—penetrated the mainstream news.

The story expanded beyond Gosnell and suddenly lifted a curtain to reveal larger systems that not only allowed but enabled Gosnell’s crimes to go unchecked for decades. His case demonstrated how abortion culture permeates the regulatory environment, the community health care environment, the media environment, and even the criminal justice system. It also showed, in a particularly grisly fashion that could not be ignored, how all of these failed systems collectively degraded the value of human life.

In Gosnell, McElhinney and McAleer quote former Pennsylvania governor Tom Corbett as saying, “This doesn’t even rise to the level of government run amok. It was government not running at all.” They go on to say that “Corbett called the failures at the Department of Health and Department of State ‘despicable.’ He flexed his executive muscle, sacked six managers, and started updating the state regulations that govern abortion clinics.”

As a lobbyist for almost 15 years, I saw up-close the impact of the abortion industry. I once sat in a meeting with the director of a state health department who argued unashamedly in front of a state senator that it didn’t matter if abortion providers didn’t comply with state reporting laws because, well, “abortion politics.” Never mind that his passion was improving public health—he wouldn’t enforce the law because of abortion politics.

This same argument is used often in other settings. I once argued with prosecutors and other law enforcement officials who cited “abortion politics” as their reason for opposing better legal protection for 14-year-olds who are made vulnerable to adult sexual exploitation. In sum, they didn’t want backlash from the pro-abortion community. I’ve also debated with reporters who won’t write about abortion because they’ve been given unreliable information from the pro-life community and don’t want to cross the abortion establishment in their communities.

The Gosnell case—and the Planned Parenthood videos that emerged two years later—exposed the entrenched, self-protective thinking that plagues these multi-faceted systems. And while laws will never prevent all criminal conduct, these systems can be improved to minimize harm to both born and preborn members of our communities.

As we reflect on the legacy of the Gosnell case, we in the pro-life community have the opportunity to learn several important lessons that will help us better achieve our goals of advancing dignity and protection for all human beings:

1. Be gracious and humble when the truth of our message is corroborated by external events.

When we’ve fought for decades for the life of innocent babies, a story like Gosnell can easily put us in a posture of “See, I told you so!” However, we need to resist this attitude at all costs. If we want to save lives, we need to gently convince those who disagree with our view. Gracious, humble speech born out of love is essential to effective persuasion.

After the Gosnell case, I encountered openness among some of my self-described pro-choice friends, who wanted to discuss where systems had failed and ensure that it never happens again. In those conversations, I witnessed changes of heart and mind. If these friends had been confronted by self-righteous superiority, they likely would have declared Gosnell an anomalous case and simply moved on.

2. Resist the urge to overreach; it poisons our cause.

We need to get our facts straight. As pro-life advocates, we have the truth on our side. We don’t need hyperbole and fear tactics. In the wake of Gosnell (and other comparable cases), nothing could be less effective than to suggest that every last pro-choice person is his equivalent. It’s untrue and unhelpful. We should be cautious and painstakingly accurate in the information we provide to constituents, social media followers, parishioners, and friends. Here again, those we need to persuade will never give us a hearing if we aren’t careful with our words.

3. Understand that many self-identified pro-choice advocates are motivated by compassion and believe they’re helping women.

A colleague once asked me how I know that many pro-choice advocates have benevolent motives. “Because I know them—lots of them,” I said, referring to my pro-choice friends and contacts, “and so should you.”

More often than not, we’re more comfortable spending time with people who think like we do, but isolating ourselves is not an effective method of child advocacy. We don’t need to deny the malevolent motives on the part of some pro-choice advocates, but we can’t paint all self-described pro-choice people with the same broad brush.

After Gosnell, many of my pro-choice friends were as horrified about the case as my pro-life friends, and many were eager to distinguish their principles from his. This led to productive conversations that moved their views just a bit—which is no small matter.

4. Get involved in all sectors of the community. Don’t self-segregate.

We need pro-life people working and volunteering in all the areas of influence highlighted by the Gosnell case: public health, community health care, state government, law enforcement, criminal justice, and public policy. And we need pro-life people in every political party and in every part of the community. We can’t change hearts and minds if we don’t show up.

5. Create strong and sincere relationships with people with whom you disagree.

At least one person in the Gosnell tragedy—the reporter who broke the story and made it national news—cited a relationship with a pro-life friend as a catalyst for why she pursued the story. Although she verified and sourced her facts independently, that personal relationship compelled her to investigate the case. As a result, the entire trajectory of our national conversation changed.

We know from Scripture that loving God and loving our neighbor are the greatest commandments, and that our love for others is an extension of our love for God. As Christ said to his disciples, “Truly I tell you, whatever you did for one of the least of these brothers and sisters of mine, you did for me” (Matt. 25:40). Nothing we do as pro-life advocates or as followers of Christ will count for much if it’s done without love—love for every human being made in the image of God. This love in action is essential to the pro-life movement, especially as we serve girls and women who feel abortion is their only choice.

The Gosnell case offers a glimpse into one of the greatest human rights struggles of our time, and the horrors that took place at 3801 Lancaster remind us to redouble our advocacy efforts. There are lives at stake, and those lives matter to God. As long as we allow his love to guide us as we advocate for the dignity and worth of all human life, then our cause has a future.

Kelly Rosati is the vice president of community outreach at Focus on the Family and serves as the ministry spokesperson on sanctity of human life and adoption and orphan care issues. She and her husband, John, live in Colorado Springs with their four children.