To the fathers of secularization theory, it was obvious. Max Weber, Emile Durkheim, and Karl Marx theorized that the more advanced and educated a society became, the less it would need that “opium of the masses”: religion.

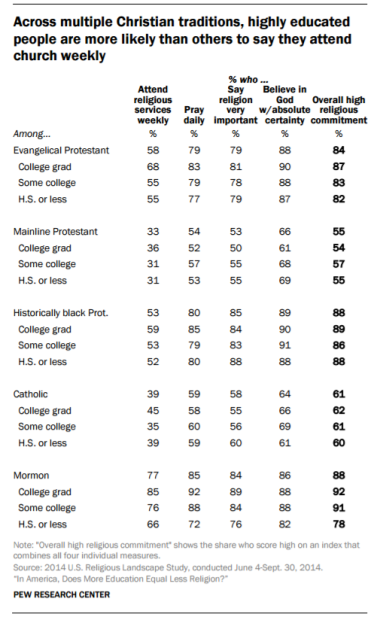

Not among US Christians, according to a new study from the Pew Research Center. In fact, among evangelicals, more education correlates with a higher religious commitment in every area that Pew researchers asked about.

Evangelicals who graduated from college are more likely than those who didn’t enroll to attend religious services at least weekly (68% vs. 55%), to pray daily (83% vs. 77%), and to believe in God with absolute certainty (90% vs. 87%). They’re also more likely to say religion is very important to them (81% vs. 79%).

Those numbers aren’t a fluke; when Pew broke the categories down further, the trend continued. Evangelicals who earned a graduate degree after college are the most committed to their faith; those who dropped out of high school are the least committed.

For example, 55 percent of evangelicals who didn’t finish high school now attend church at least once a week. Among evangelicals with a postgraduate degree, that number shoots up to 70 percent.

Evangelicals with a graduate degree are more likely to pray every day (83% vs. 77% of high school drop-outs), to believe with absolute certainty in God (90% vs. 81%), and to say religion is important in their lives (84% vs. 82%).

On Pew’s religious commitment index, 87 percent of postgraduates scored “high,” compared to 81 percent of those who didn’t graduate from high school.

The gap was smaller among historically black Protestants (two-thirds of whom are evangelicals, according to Pew). Even so, more black Protestants with a postgraduate degree reported attending religious services once a week (62% vs. 56% of high school drop-outs), praying at least once a day (83% vs. 78%), and believing firmly in God (91% vs. 89%).

The only category where those who went to graduate school lagged behind high school drop-outs was claiming that religion was very important in their lives (84% vs. 89%).

That trend is reflected in the larger Christian category—which includes mainline Protestants, Catholics, and Mormons along with evangelicals. The importance of religion was the only category where Christians in general saw a drop as education levels climbed.

About a third of Christian college graduates said religion was very important (64%), compared to 70 percent of those who topped out at high school.

But their actions—attending worship services, praying, and believing in God—held steady, regardless of educational attainment.

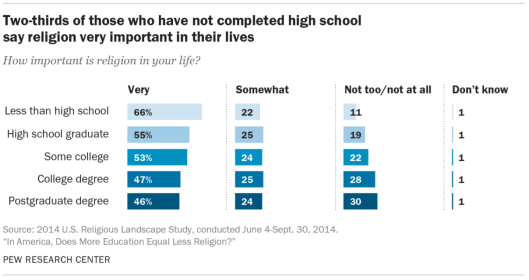

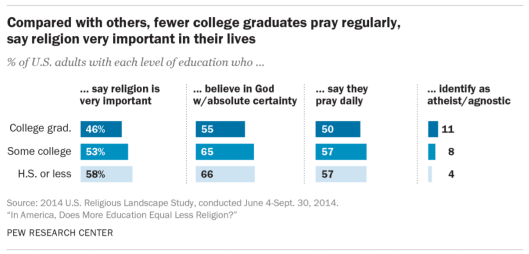

The numbers are baffling, because on the whole, Americans do report lower levels of religiosity as they gain more education. Those with a higher level of education are less likely to believe in God (55% of college graduates vs. 66% of those with a high school degree or less), to pray (50% vs. 57%), and to say religion is very important to them (46% vs. 58%)

Even Pew doesn’t have a theory, reminding readers that “there could be many possible reasons for these patterns, though such explanations are outside the scope of this report.”

“This analysis does not attempt to explain why, for example, Americans with more education are less likely to express belief in God,” the report stated. “Nor does it try to explain why college-educated Christians appear to go to church more often than less-educated Christians. The focus here is simply on describing the patterns found in recent [Pew] polling.”

But those patterns do shed some light. Pew broke down the Christian category, which included 71 percent of respondents. While evangelicals and Mormons grow across-the-board more religiously committed as they gain education, while other categories of Christians do not.

Mainline Protestants who have graduated from college are more likely to attend church once a week (36% vs. 31% with a high school diploma or less), but lag behind their lesser-educated counterparts in all other categories.

Catholics show the same pattern: Those with a college degree are more likely to attend mass at least weekly (45% vs. 39% of those who didn’t continue past high school), but fall slightly behind in other categories. Their overall scores are almost exactly the same: 62 percent of college graduates and 60 percent of those with who didn’t go to college have a high religious commitment overall.

Interestingly, Catholics with graduate degrees are the most likely to attend mass at least weekly (50%); overall, they had the highest percent of members with high religious commitment (65%).

Another factor is the low religious commitment levels of educated Jews and religious nones. These groups are among the most likely to pursue further education, and the most likely to lose religious practices along the way.

Nearly a third of American Jews reported having a graduate degree in 2014 (31%), compared to 16 percent of atheists and agnostics, 14 percent of mainline Christians, 10 percent of Catholics, and just 7 percent of evangelicals and 6 percent of historically black Protestants.

More gained a bachelor’s degree, though Jews (29%) and atheists/agnostics (about 25%) were still ahead of mainline Christians (19%), Catholics (16%), evangelicals (14%) and historically black Protestants (9%).

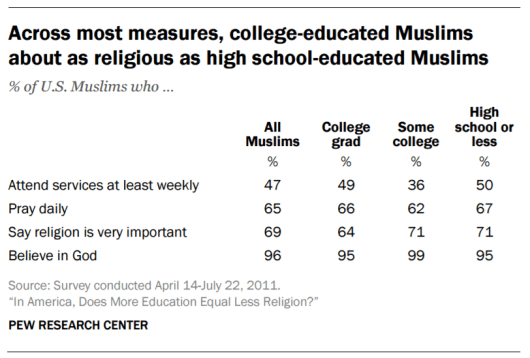

Muslims were about as likely as nones to continue their schooling (23% had bachelor’s degrees and 17% had graduate degrees in 2014), but their levels of religion were much less likely to change. The only noticeable difference was how important religion was to them: 71 percent of those who didn’t go to college said it was very important, compared with 64 percent who graduated from college.

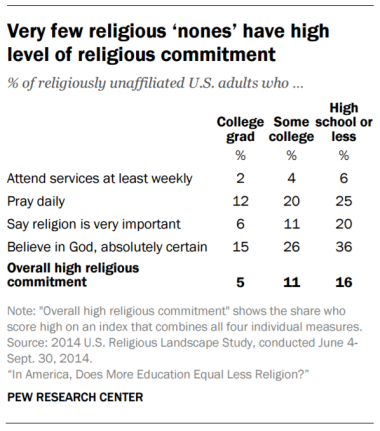

Religious nones, on the other hand, were twice as likely to show levels of religious commitment if their education didn’t extend past high school than if they graduated from college. (Though, it could also be argued that their commitment to atheism or agnosticism actually did increase with their level of education.)

Nones who graduated from college are significantly less likely than those who didn’t go at all to attend religious services weekly (2% vs. 6%), to pray daily (12% vs. 25%), to believe in God with certainty (15% vs. 36%), or to say religion is very important to them (6% vs. 20%).

The spread was even wider when Pew broke the categories down further. Nones who went to graduate school were far less likely than those who didn’t finish high school to attend worship services once a week or more (1% vs. 10%), to pray daily (12% vs. 36%), to believe in God (13% vs. 43%), and to say religion is important to them (3% vs. 31%).

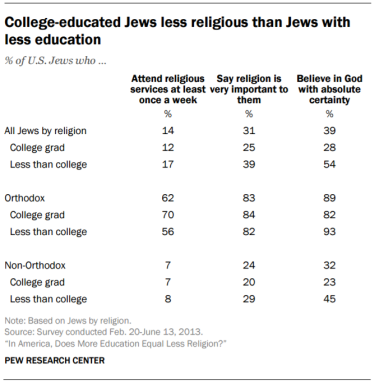

Jewish religious commitment dropped also, though not quite as far. This may be because Pew didn’t break out the high school graduates from those who didn’t finish high school.

Those who obtained a high school degree or less were twice as likely as those with graduate degrees to attend religious service at least once a week (23% vs. 11%), to believe in God (58% vs. 24%), and to say religion was very important to them (50% vs. 24%)—although the numbers among the Orthodox were more likely to look like evangelical numbers.

Orthodox Jews who graduated from college were more likely to attend religious services at least once a week and to say religion is very important to them, though fewer believe in God with absolute certainty.

“The idea that highly educated people are less religious, on average, than those with less education has been a part of the public discourse for decades,” the report stated.

Turns out “the relationship between religion and education in the United States is not so simple.”