Editor’s note: Due to a computational error made in the original April 30 posting, certain figures and charts have been updated as of May 3.

The 2016 presidential election heightened an ongoing discussion over the allegiance of American evangelicals to the Republican Party.

As countless articles and social media posts have observed, Donald Trump’s presidency has led many church leaders to warn against a too-warm embrace of politics and politicians, as well as led many Christians to rethink their involvement and identity as evangelicals.

Though these tense conversations may feel like new ground born out of this political moment, long before Trump’s election there was already strong evidence showing that Americans’ political identities and disagreements fuel their religious identities and practices.

In other words, what we’re seeing now comes as no surprise to political scientists.

Recent research from Paul Djupe, Jake Neiheisel, and Anand Sokhey shows that over the last 15 years, people who disagreed with the political leanings of their clergy and congregations were much more likely to start skipping services or stop attending altogether. Their research before and after the 2016 election found that disagreement over Trump in evangelical churches sent a number of members heading for the exits.

In her new book, From Politics to the Pews, University of Pennsylvania professor Michele Margolis argues that partisan identities become fixed in early adulthood, a time when people tend to take a break from religion. When they consider coming back later in their 20s and 30s, they align their religion with their political identity. Typically, Democrats will stay away, and Republicans will select a Republican-aligning church.

So is evangelicalism really losing members due to disagreements over presidential candidates?

Over the past seven years (in 2011, 2012, 2016, and 2017), the Democracy Fund’s Voter Study Group has repeatedly surveyed a panel of 5,000 Americans about a variety of subjects, including their faith. The latest results, released this month, reveal trends in evangelical identity and in church attendance that correspond with voting patterns for the 2016 election.

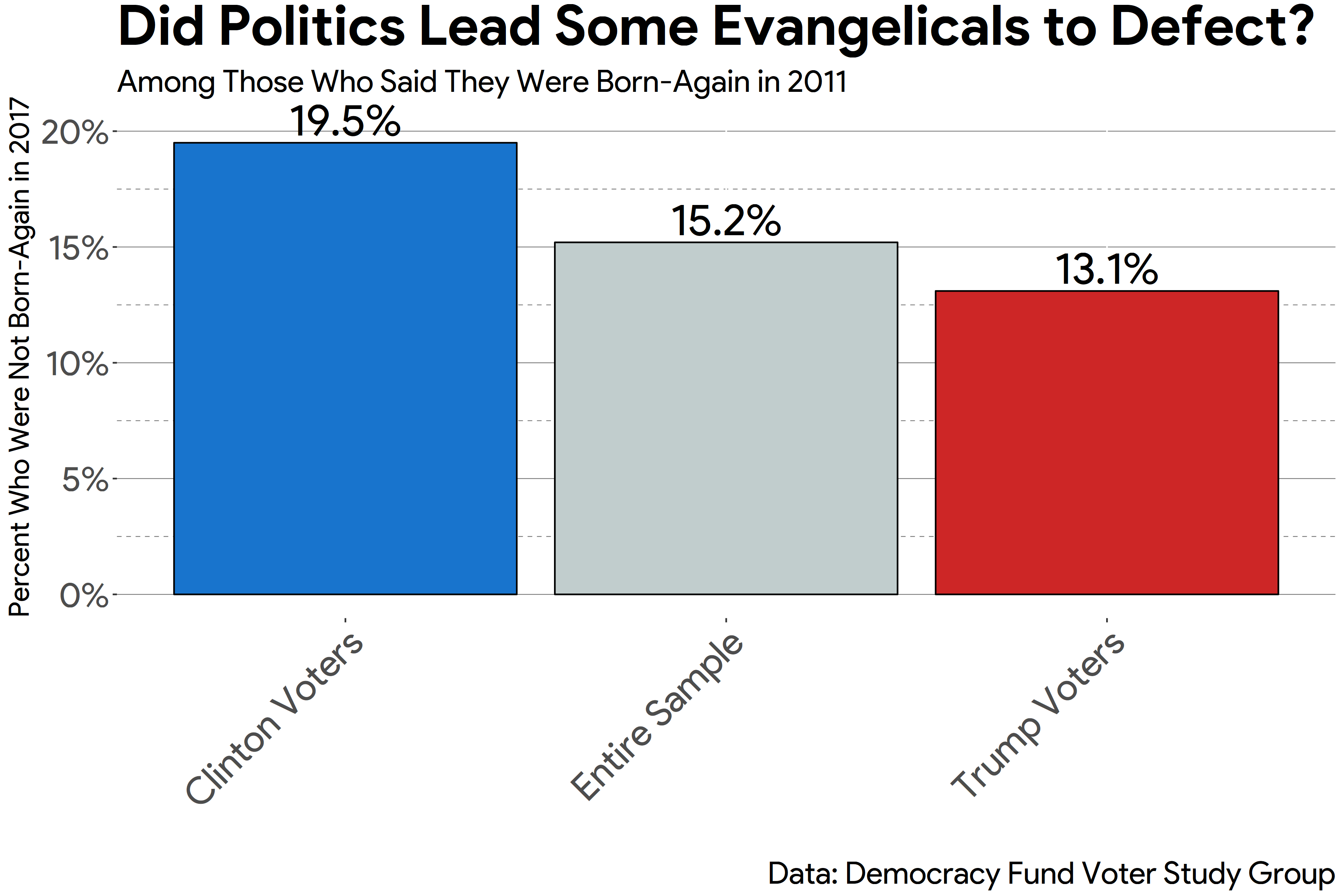

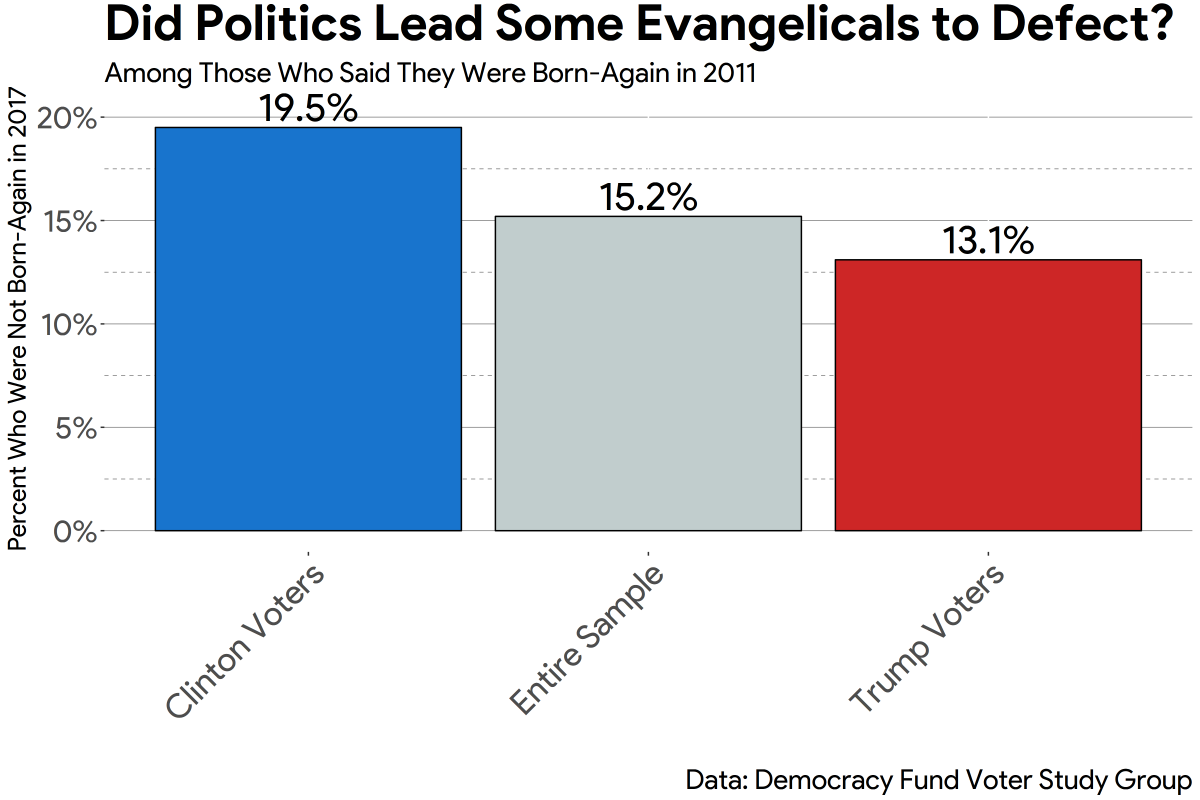

One in five Americans who voted for Hillary Clinton (19.5%) had self-identified as evangelical or born again at the beginning of the survey period but had dropped the labels (which overlap) by 2017. Clinton voters 50 percent more likely than Trump voters (9%) to stop identifying as evangelical or born-again Christians.

This trend indicates that Clinton voters did not see their choice as welcome among the evangelical community. Perhaps they felt marginalized among evangelicals to begin with, and the election provided additional motivation to find a new church home or none at all. In fact, among those who stopped identifying as evangelical or born again, 27 percent left religion altogether.

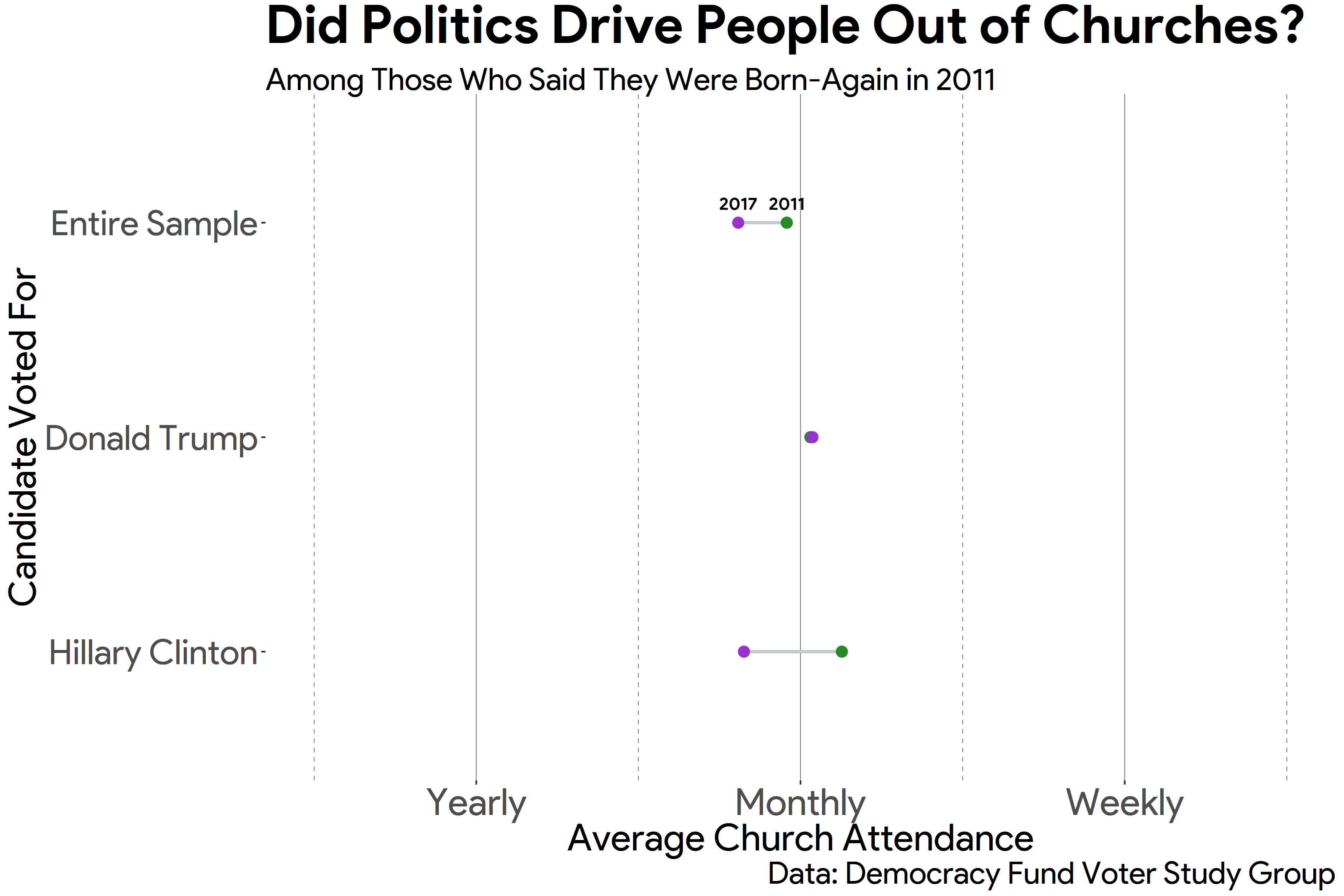

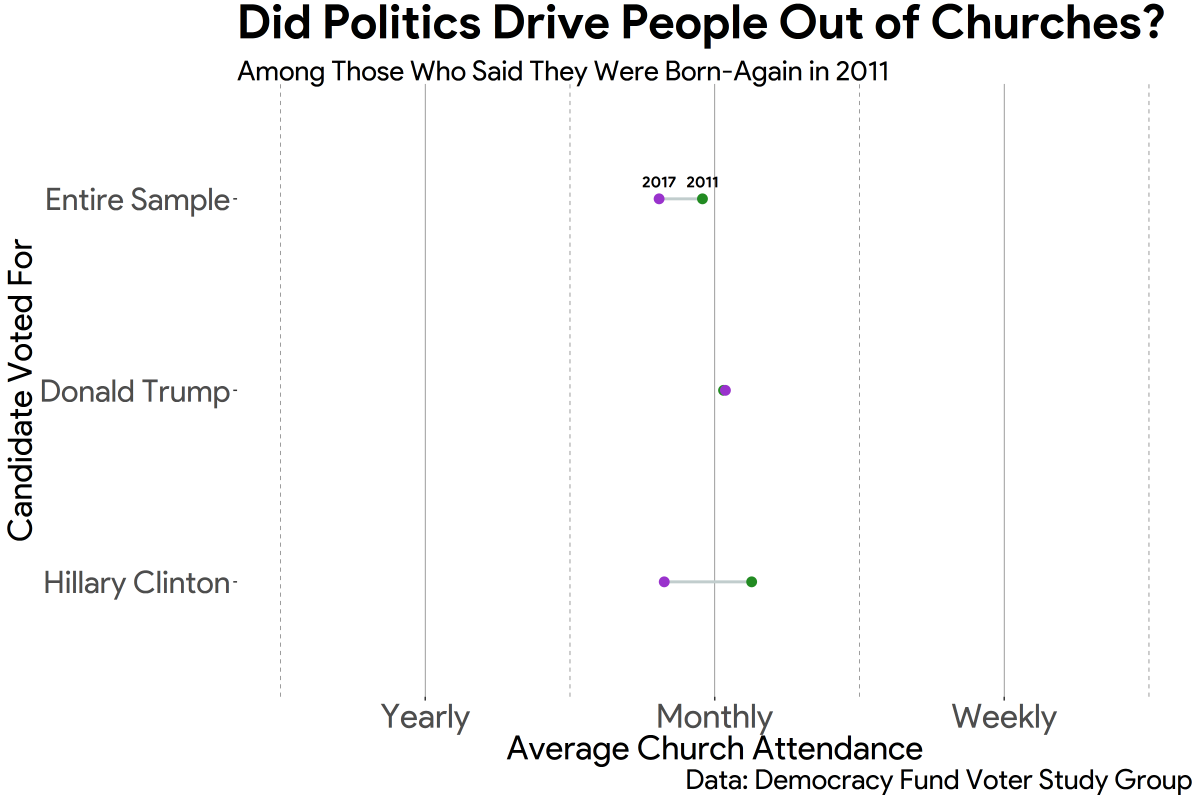

It is not surprising that there is a political pattern to worship attendance as well. Over the past several years, attendance fell among self-identified evangelical or born-again Christians, but the trend is particularly pronounced among those who voted for Clinton. Evangelical Trump voters saw no change at all in church attendance.

This evidence also confirms that such evangelicals may have been somewhat more marginal members to begin with; even at the start of the survey period, evangelicals and former evangelicals who voted for Clinton attended services less than once a month on average, while Trump evangelicals attended at least once a month.

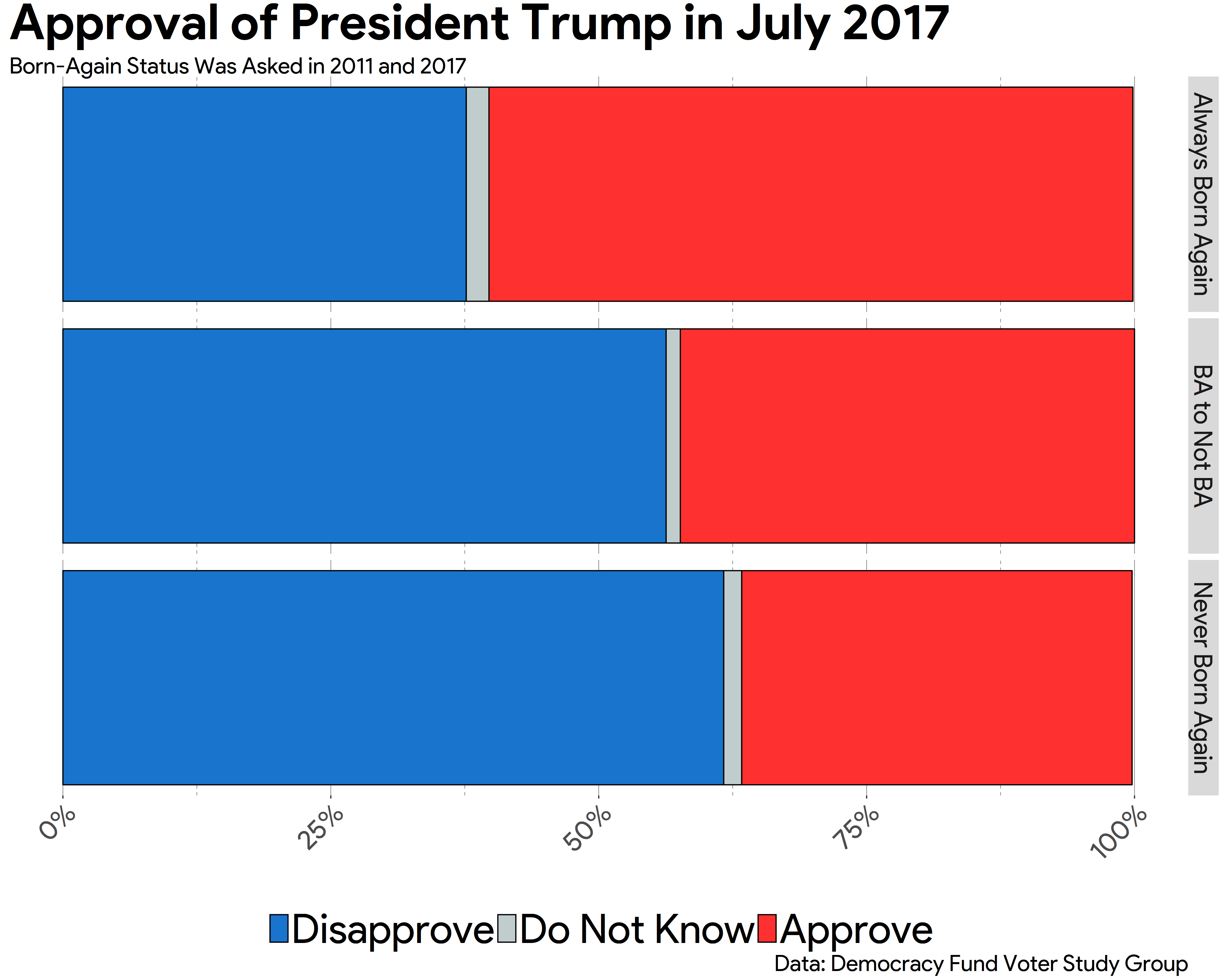

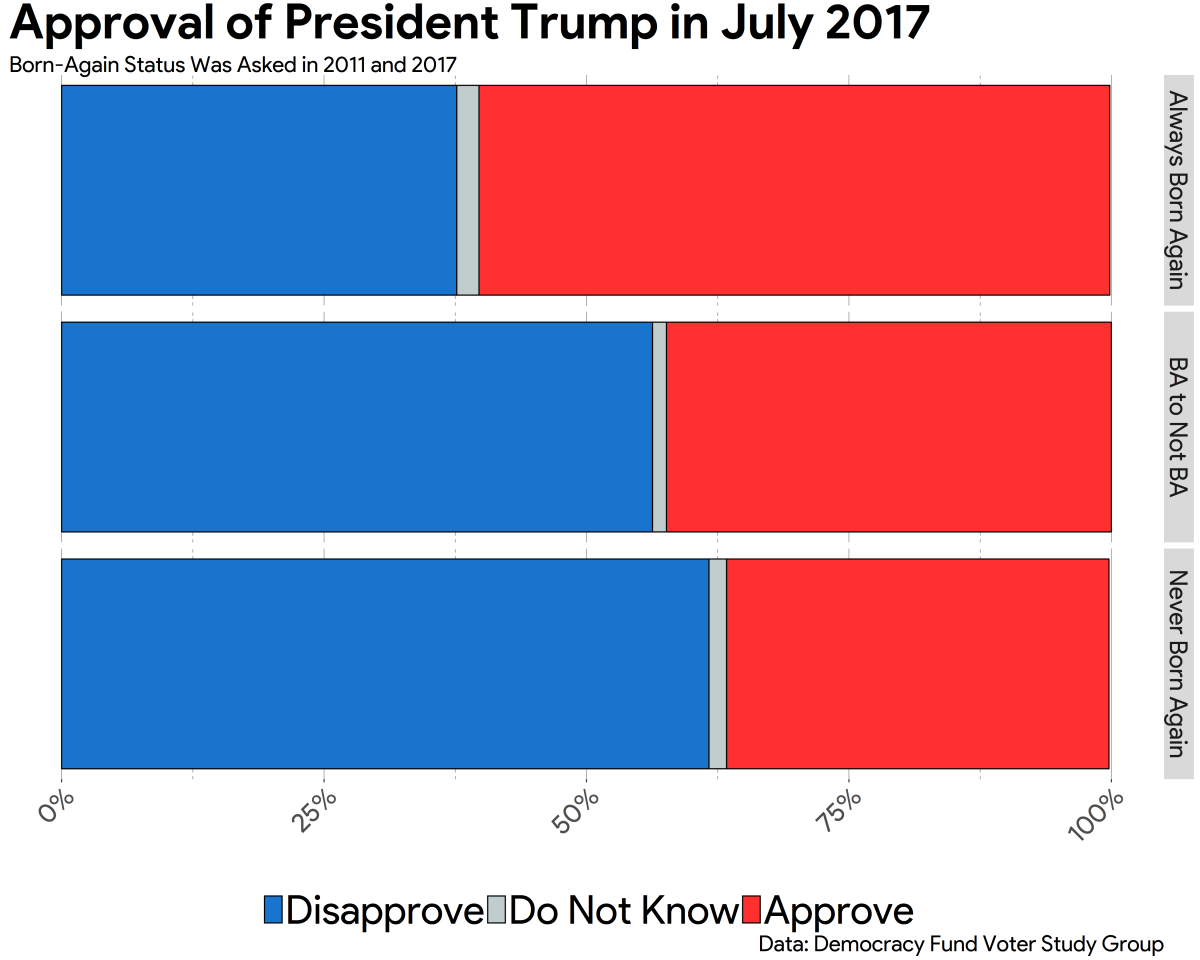

Voters who dropped their evangelical or born-again identity over the past six years were significantly less likely than those who kept the labels to approve of Trump as president.

While 54 percent of evangelicals approved of his job in 2017, voters who had previously identified as evangelical or born again more closely resembled the “never evangelical” crowd. The study found that 47 percent of former evangelicals approved of Trump, compared to 37 percent of voters who never identified as evangelical or born again.

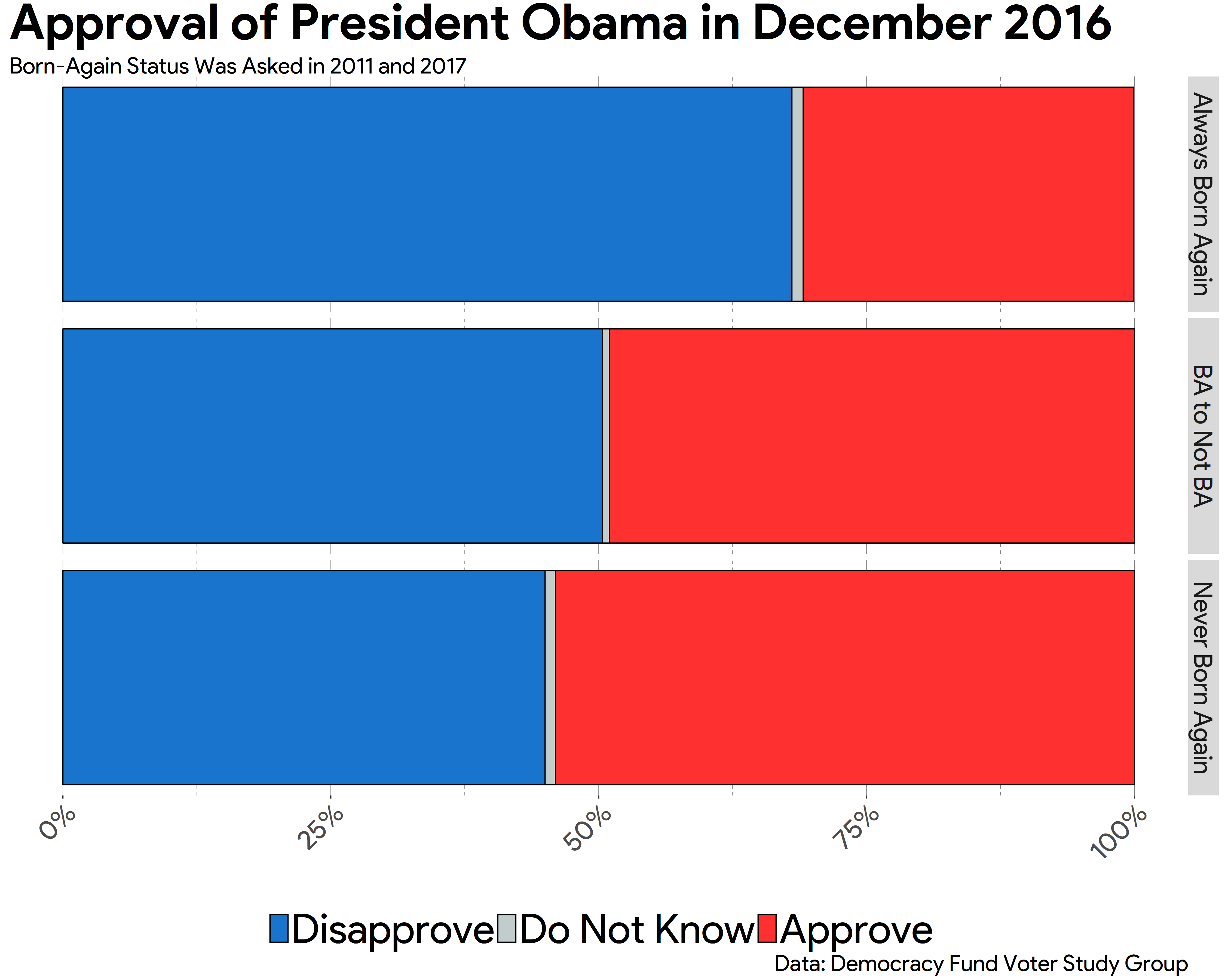

However, it’s worth noting that former evangelicals also resembled non-evangelicals when it came to approval for Barack Obama back in 2011. So it doesn’t appear that President Trump created these divisions within evangelicalism, but that his election brought them into new light. Divisions over Trump’s election became salient and confrontational enough that some dissenters opted to drop the label and/or step away from their churches.

It’s possible that one of the reasons that Trump did so well among evangelicals is because those who were averse to his candidacy renounced their religious affiliation to pollsters, leaving only evangelicals who strongly supported Trump. But the data does not confirm that narrative. Instead, voters who dropped the evangelical or born again labels between 2011 and 2016 were actually well split between Clinton and Trump: 52.5 percent vs. 47.5 percent—statistically a tie.

If evangelical disaffiliation was due to politics alone, Clinton would have fared much better than Trump. Even if this group of evangelical defectors were lumped back into the evangelical subgroup, Trump’s vote share would have dropped by only 2 to 3 percent. There were just not enough defectors to move the needle a significant amount.

The long-term fallout is not clear, but the consequences of the divide over Trump are bound to linger in America’s religious landscape. The continued rise of the religious nones has run in parallel to the involvement of the Christian Right in American politics. Marginal evangelicals, especially younger ones, have seen increasing numbers of their peers become unaffiliated in recent years, and their reasons to stay aligned with evangelicalism may be getting less and less persuasive.

Evangelicals may find that their affiliation’s alignment with Trump impacts their Christian witness if presidential scandals continue. As Washington Post columnist Michael Gerson recently argued, “If a militant atheist were to design a trap with the goal of discrediting evangelical Christians, could they do better than [Roy] Moore and [Stormy] Daniels?” In a 2016 survey of white Christians, we found that 31 percent thought support for Trump would hurt Christian witness, including 57 percent of Democrats but only 17 percent of Republicans.

The study results also indicate that American churches could benefit from being a place that welcomes, tolerates, or charitably engages voters of either party. As research has shown again and again, churches tend to be diverse places where people have the chance to work with others around a shared mission and shared faith. There are clearly Democrats in evangelical churches, given that Donald Trump did not win all the evangelical vote.

Communication scholars consistently refer to the “spiral of silence,” the idea that those who hold minority opinions intentionally remain silent in order to not alienate themselves from the group. The end result is that significant portions of the group often feel marginalized and detached. Churches would be well served to promote open dialogue and a focus on what binds a church together: a belief in Jesus Christ. This sense of unity is crucial at a time where society is continually stratifying and Americans are losing their tolerance for the political other.

These long-running patterns of disaffiliating and de-identifying because of political difference further weakens the connection of church work and democratic orientations.

Paul A. Djupe, a professor of political science at Denison University in Granville, Ohio, is an affiliated scholar with PRRI, the series editor of Religious Engagement in Democratic Politics (Temple), and co-creator of religioninpublic.blog (see his posts here). Further information about his work can be found at his website and on Twitter.

Ryan P. Burge teaches at Eastern Illinois University in Charleston, Illinois. He can be contacted via Twitter or his personal website. Full coding syntax for this analysis is available on his Github.