“It is actually reported that there is sexual immorality among you,” says Paul to the young church in Corinth. “And you are proud! Shouldn’t you rather have gone into mourning … ? Your boasting is not good,” he continues. “Don’t you know that a little yeast leavens the whole batch of dough? Get rid of the old yeast, so that you may be a new unleavened batch—as you really are. … ‘Expel the wicked person from among you.’”

One thing consistently strikes me whenever I read this passage from 1 Corinthians 5: While Paul is certainly concerned for the unrepentant man, he seems equally concerned for the sanctity of the community. “Don’t you know that a little yeast leavens the whole batch of dough?” he asks. The basis for Paul’s concern seems to be his understanding that God dwells not simply in the redeemed individual but among the whole community. “Don’t you know that you yourselves are God’s temple and that God’s Spirit dwells in your midst?” he asks (1 Cor. 3:16).

Throughout his letters, Paul teaches that the church currently enjoys the presence of the Spirit of God in anticipation of the day when God will flood the whole earth with his glory. Similarly, John’s closing vision in Revelation makes plain the hope of a renewed heaven and earth in which “God’s dwelling place is now among the people, and he will dwell with them. They will be his people, and God himself will be with them and be their God.” (Rev. 21:3). Consequently, these passages should remind us that holiness—the quality that makes creatures capable of inhabiting the same space as their Creator—is not just an individual concern but is also a corporate affair.

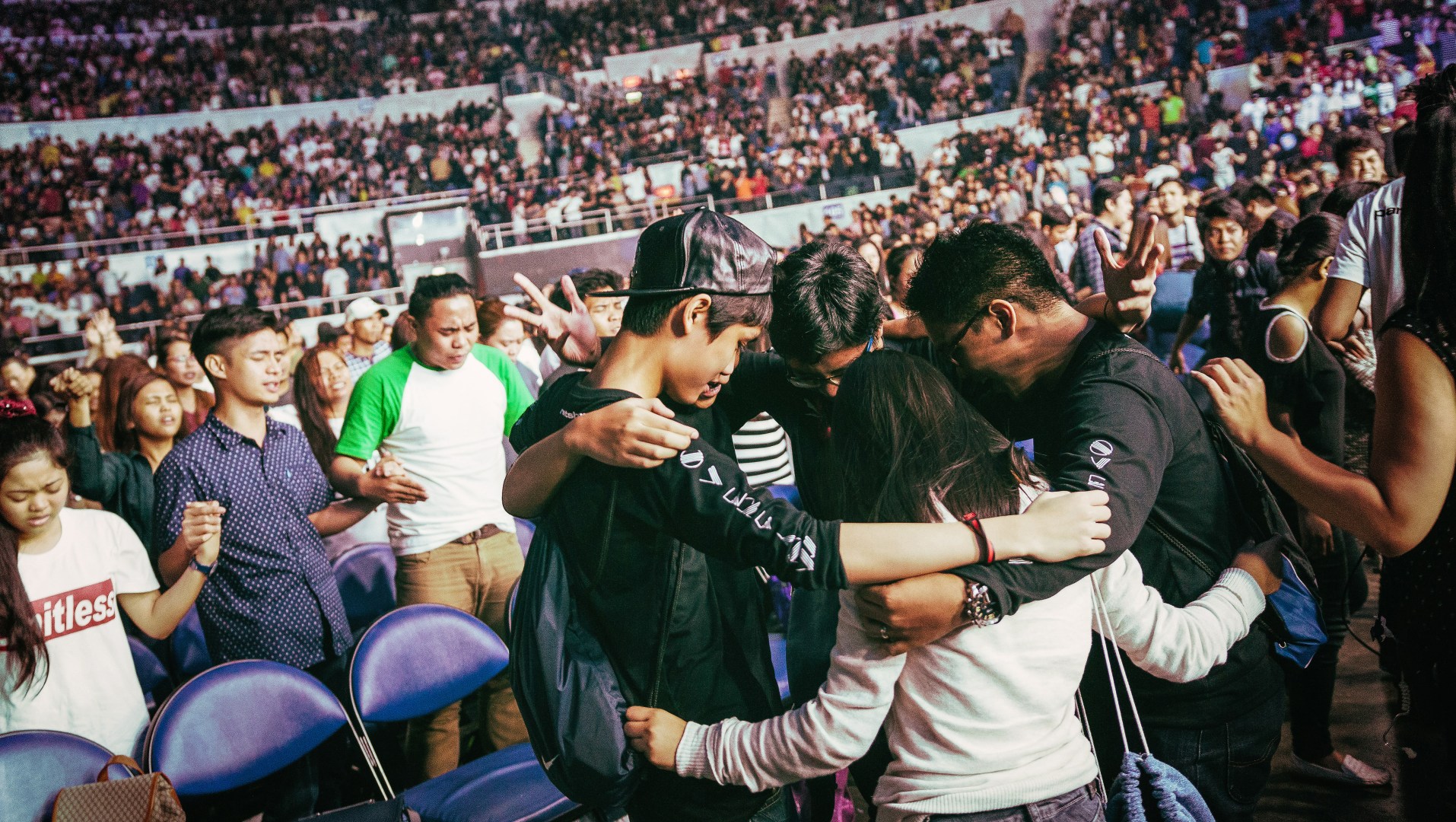

Certainly, individual sanctification matters greatly, but it gains its significance within the broader biblical vision of the Triune God making his dwelling among his rescued people. In other words, holiness should be a characteristic of the community, and an individual grows in his or her personal holiness by submitting to God’s Spirit who sanctifies the whole.

In this time between the times, recalling the biblical vision of the whole community as the restored, sanctified dwelling place of God will greatly empower our Spirit-led efforts toward communal and personal holiness, equip our churches to respond rightly to communal and individual shortcomings, and serve God’s mission in the world by reminding us that the corporate church should shine like lights in a watching world full of alternative portraits of what it means to be human (Phil. 2:15).

The Numinous Presence

God’s Spirit among us is the basis for the apostles’ exhortations to holiness: “Be holy because I am holy.” (Lev. 11:44–45, 19:2, 20:7; 1 Pet. 1:16) The often-unstated premise in this well-known refrain is “Because the Lord your God walks in the midst of your camp.” (Deut. 23:14, ESV). God’s presence is likened to a “consuming fire” (Heb. 12:29; Lev. 9:24), but here an interesting phenomenon occurs. Though his presence is like fire—a terrible good—we are not thereby warned to avoid him, as one would toddlers near an open flame. Rather, we are required to become pure steel rather than dry wood, capable of enduring the intense heat. Like the Pevensie children upon learning that Aslan is not a tame lion, our right response is not to run in the other direction but to approach him with awe. In other words, we are to be holy as he is holy.

Thus, the fact of God’s spiritual presence among us now, and the promise of his unveiled presence in the future, is what grounds New Testament exhortations to both individual and communal holiness. But it’s important to remember that holiness isn’t just a lack of impurity any more than fire is a lack of darkness. To be sure, holiness entails the avoidance of impurity, but it is more aptly described by its positive characteristics, by the fruit the Spirit bears: love, joy, peace, and the rest. While we easily comprehend exhortations to personal holiness, communal holiness can be an odd concept given the Western penchant for individualizing sanctification. So what would it look like for a whole community to be characterized by holiness?

The early church provides numerous examples. One such is the distinctive practice of adopting orphans. Ancient societies widely practiced “infant exposure,” the abandonment of unwanted children to the fate of death or slavery. Not only did Christians condemn the practice (see Epistle of Barnabas 19:5, 20:2; Epistle to Diognetus 5:6), but they were even known to rescue exposed infants and raise them as their own (see Augustine, Epistle to Boniface §6). Thus, in a culture that valued or defined a person by virtue of their perceived benefit to society, Christians exhibited their communal holiness by disregarding such cultural norms and consequently caring for unwanted children as a community at great cost to themselves.

Similarly, in imitation of Jesus’ vision that God’s dwelling place is a place of transformation for the sick and needy (inferred from Matt. 21:14) my church in Houston, Seven Mile Road, raised and dedicated over $60,000 to Houston’s Child Protective Services and the church’s own Adoption and Foster Care Fund, financially aiding folks in our community who foster and adopt. Time with these children and their caretakers continually awakens our church to the reality of Houston’s need, and as a result, numerous couples within the church have become foster parents and adopted children into their care. Thus the Spirit that indwells us as God’s people led the church to pursue love and goodness toward those around us, in and out of the household of faith (Gal. 6:10), such that in a city with staggering need, Seven Mile Road is known for its service to the least of these.

To be sure, at an observable level, holy endeavors like the ones described above are often initiated and completed by individuals. But it’s important to remember the basis for such individual acts. Members of the community are able to act accordingly not because of their personal holiness but because they belong to the sanctified body, whose head is Christ (Col. 1:18; 1 Cor. 12).

Even the term member implies a proper functioning only by virtue of one’s belonging to the whole. Members act rightly as “hands” and “feet” precisely because they belong to the holy “body.” Personal holiness, therefore, is a consequence, not a component, of communal holiness. Thus individuals pursue and express their sanctification only by submitting to the Spirit that already sanctifies the corporate church.

In the two examples above, from the early church and Seven Mile Road, members of the church were empowered and encouraged toward radical acts of love and faithfulness because their churches, as corporate bodies, committed to embodying the love of Christ in their communities.

Equipping the People of God

Importantly, this same Spirit who leads us into holiness also equips us to react rightly when faced with individual and communal failures. Indeed, in the example from 1 Corinthians 5 above, Paul is concerned for the immorality of the individual because of his conviction that the Spirit sanctifies the whole people. “Don’t you know that a little yeast leavens the whole batch of dough?” he asks (1 Cor. 5:6). “Are you not to judge those inside [the church]?” (1 Cor. 5:12).

The logic of Paul’s understanding is well-grounded both in Israel’s priestly literature and in our everyday experience. Basically, sin acts like a contagion; when left undealt with, it spreads and contaminates those who come into contact with it yet do nothing to set things right. Like a single pebble thrown into a pond, the ripple is much wider than the single point of impact.

We recognize this reality in the many #MeToo and #ChurchToo examples that have recently made news. What often began as a bent desire in the mind of say, a male leader in a church—a private moment indeed—spiraled out of control, sprouting tentacles that dragged others down into a dark, dark place. It is thus incumbent upon the church to right such wrongs, to work on behalf of the victims, and to protect the vulnerable from such abuses.

But thankfully not all examples have such sinister outcomes. Indeed, my hope is that this biblical vision of corporate holiness spurs our Christian communities to seek both the vindication of the harmed and the restoration of the one who falls short. A church from my childhood—one that focused on aiding recovering drug addicts—modeled this well.

Early one morning my pastor received a call. “We can’t find him,” said the voice on the other end. “And he hasn’t showed up for work in a while.”

Dale was a faithful member of the church, and he had come to know the Lord and attend services through the church’s outreach programs. The church had funded Dale’s rehabilitation, helped him attain a job, and provided accountability systems to help sustain his substance-free life. However, one week Dale didn’t check in and he was unreachable by phone. The pastor and some members eventually visited his home but could find no trace of him. Finally, he turned up at a friend’s house, and it was clear he had fallen back into some old, destructive habits.

But our church didn’t blink. Marked with gentleness and humility, the community sat with Dale and talked through what prompted his recent actions, reminding him of the church’s love for him. And Dale wept.

He was received by the community with open arms and prayed for publicly, and he continues to this day in joyful fellowship with the church. In this case, not only was Dale himself restored through repentance, but the potential negative communal effects of his momentary shortcoming, namely the temptation of the church’s many other addicts, were minimized from the beginning.

And this is the beauty of God in his temple, among his people: The Spirit who indwells us is also the Spirit who sanctifies us, empowering us to obey God’s commands and leading us to repentance when we do not. It is the only place that requires we become like Jesus, enables us to do so, and forgives us when we don’t. For God alone demands such holiness for those in his presence, and he alone provides the means of doing so.

Finally, this Spirit who indwells us also molds us into the people we were created to be, shaping our communities into Christ-like bodies and serving God’s mission by showing a watching world that there is another way to be human.

The Mission of God

“By this everyone will know that you are my disciples, if you love one another” (John 13:35). Love of one another is to be an unmistakable mark of our Christian communities, and though it is a good in itself, such love also beckons the rest of creation to be reconciled to God and join the community indwelt by the Spirit. For God’s Spirit shapes us into “little Christs,” to use C. S. Lewis’s phrase, sending us into the world as Christ was sent to us.

“‘Peace be with you! As the Father has sent me, I am sending you.” And with that he breathed on them and said, ‘Receive the Holy Spirit.’” (John 20:21–22).

This Spirit among us—the fire that burns away our impurities—also casts needed light on a world over which shadow spreads. Thus in an onlooking world rightly concerned for justice, the community functioning as God’s temple serves as a signpost of the new creation in which love, empowered by the Holy Spirit and expressed by sacrifice, patience, and forgiveness, marks the lives of our communities and invites the watching world to participate.

Our communities, then, should be characterized, however imperfectly in the present, by the kind of holiness that will pervade the new creation in which God will be all in all. To be God’s temple in the present is a terrifying good, certainly, but it is one that promises to transform us into Christ’s image until he finally makes all things new, when the tabernacle of God will be among humans, and he will be their God, and they will be his people, and God himself will be among them.

Paul Sloan is assistant professor of theology at Houston Baptist University. His most recent book is Mark 13 and the Return of the Shepherd: The Narrative Logic of Zechariah in Mark (T&T Clark: LNTS, forthcoming).