During his sabbatical at the end of last year, Chance the Rapper quit smoking while studying Scripture. “I feel really good right now, thank u Father,” he wrote on Instagram, where he shared passages of Scripture and counted days gone by without another cigarette.

The Chicago native, who has become outspoken about his walk with Christ in his music and public life, is one example of a trend researchers found among the faithful: Believers who are active in their faith tend to make healthier choices and live happier lives.

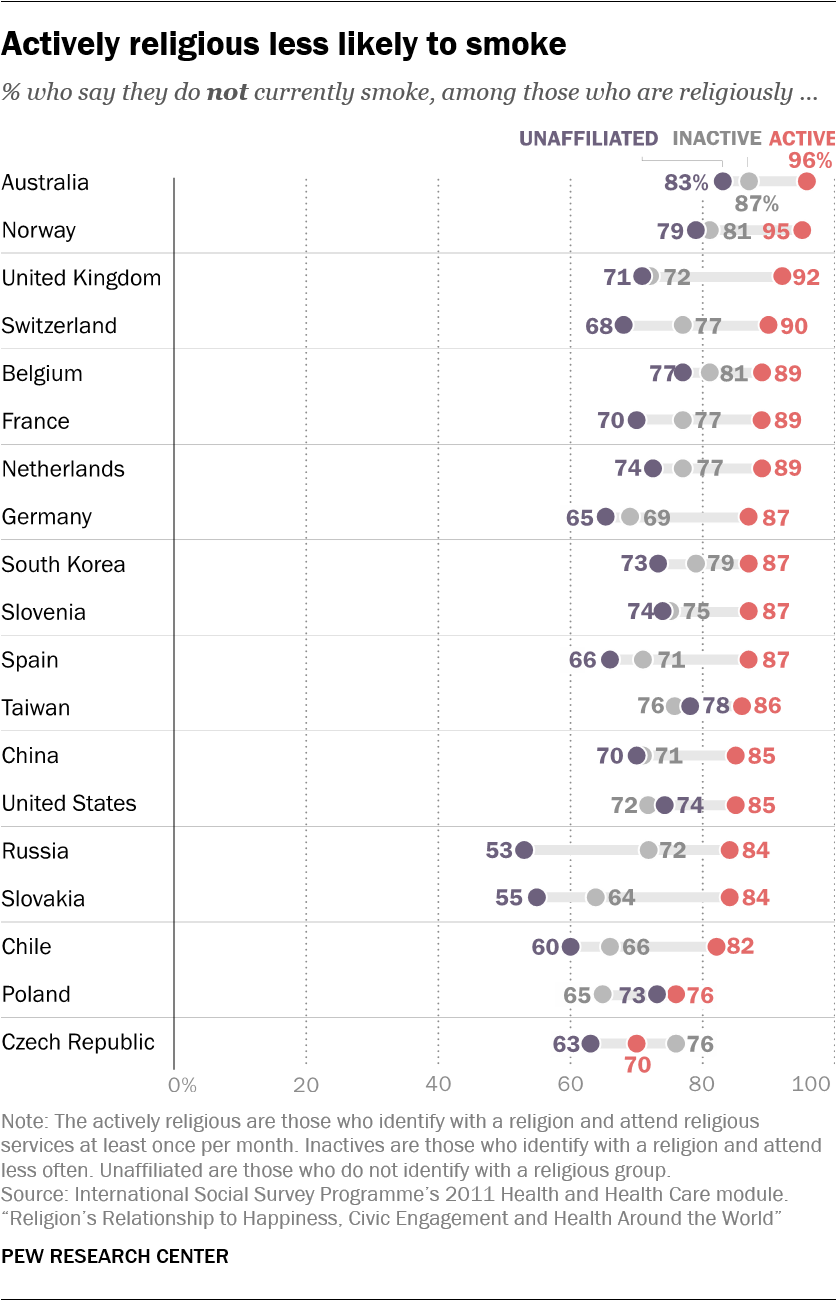

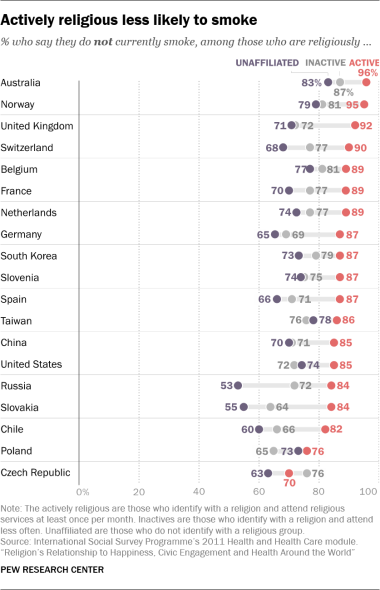

Religious habits make a major difference for smoking status in particular, according to a Pew Research Center report released today on religion and well-being.

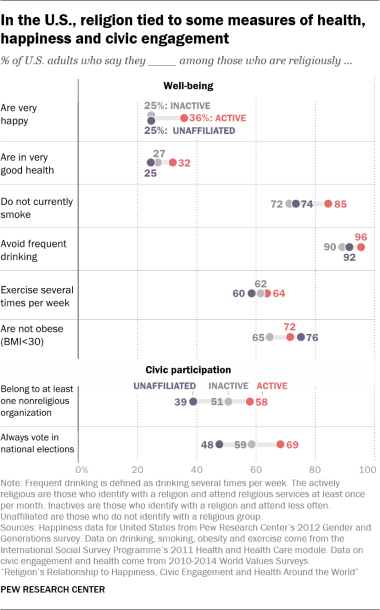

Among Americans who identify as Christian or another religious tradition and attend services at least once a month, 85 percent don’t smoke, compared to 74 percent of the religiously unaffiliated and 72 percent of those who attend services less often.

The trend holds up around the world, where regular worshipers are less likely to smoke by a significant margin in 16 of 19 countries surveyed. (In most of those places, the active religious also drank less, but not by as wide a margin.)

Smoking and drinking were among several measures of wellbeing analyzed in the new report, based on data from the World Values Survey (2010–2014), the International Social Survey Programme, and Pew surveys.

Religious attendance—rather than religious affiliation—consistently linked to higher levels of happiness than the growing population of people around the globe who claim no faith. The report said:

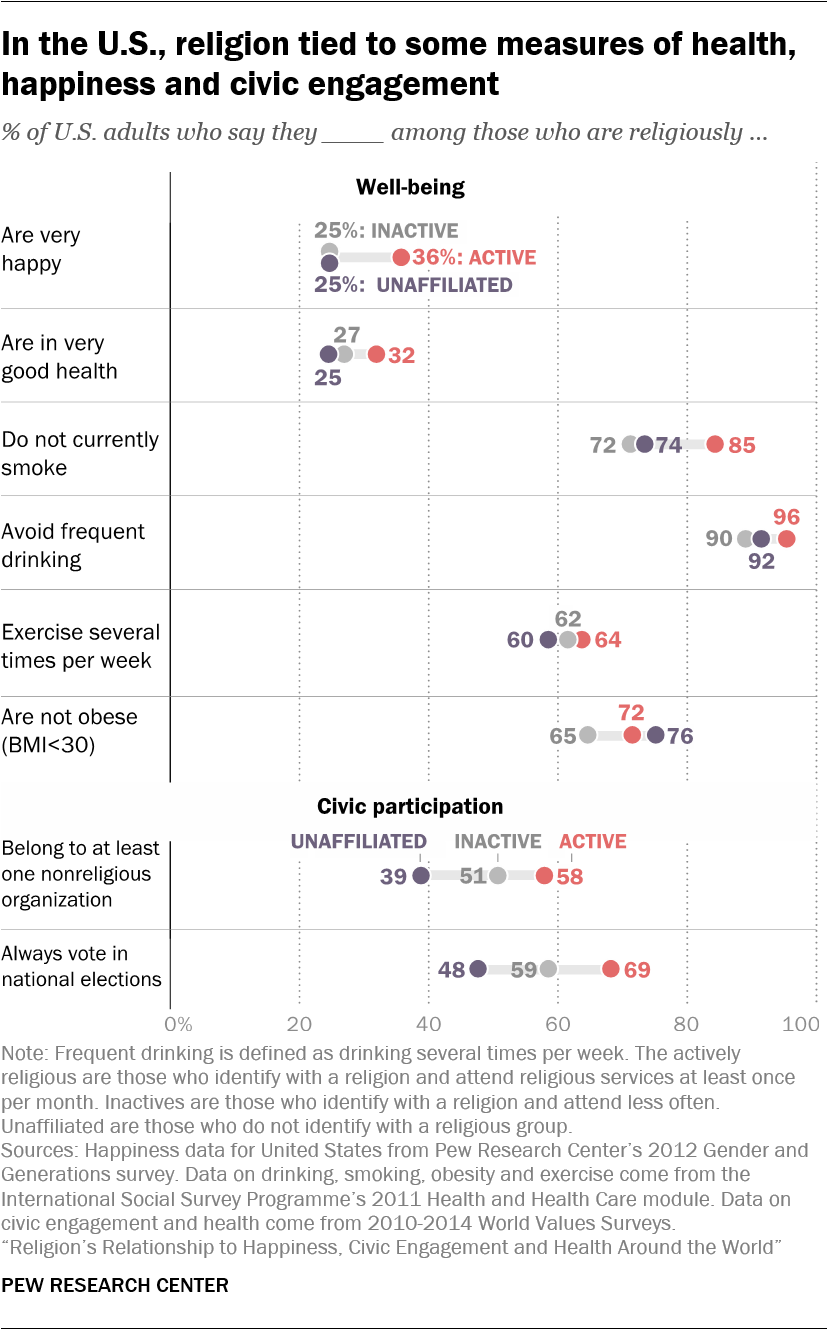

Whatever the explanation may be, more than one-third describe themselves as very happy, compared with just a quarter of both inactive and unaffiliated Americans.

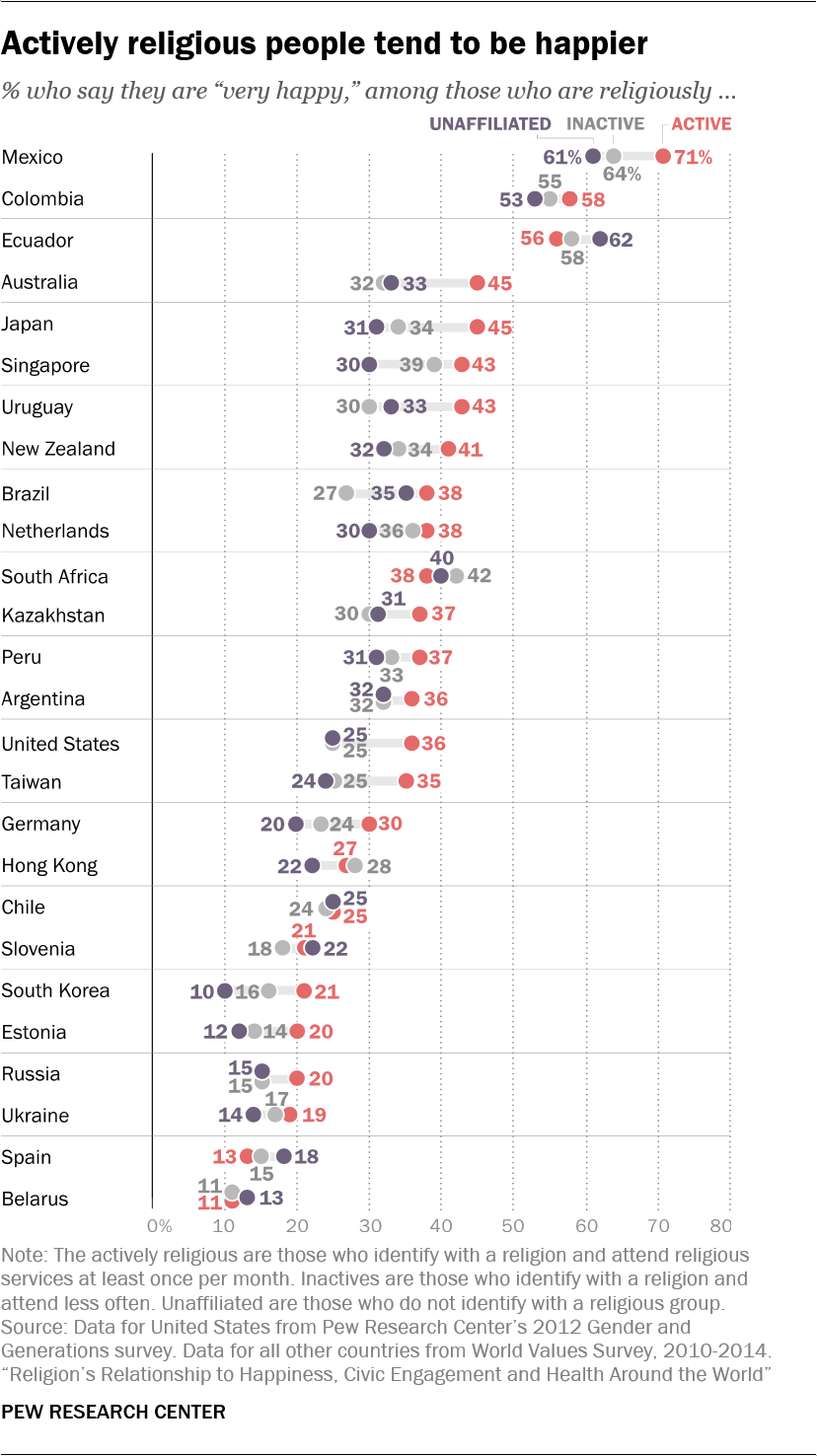

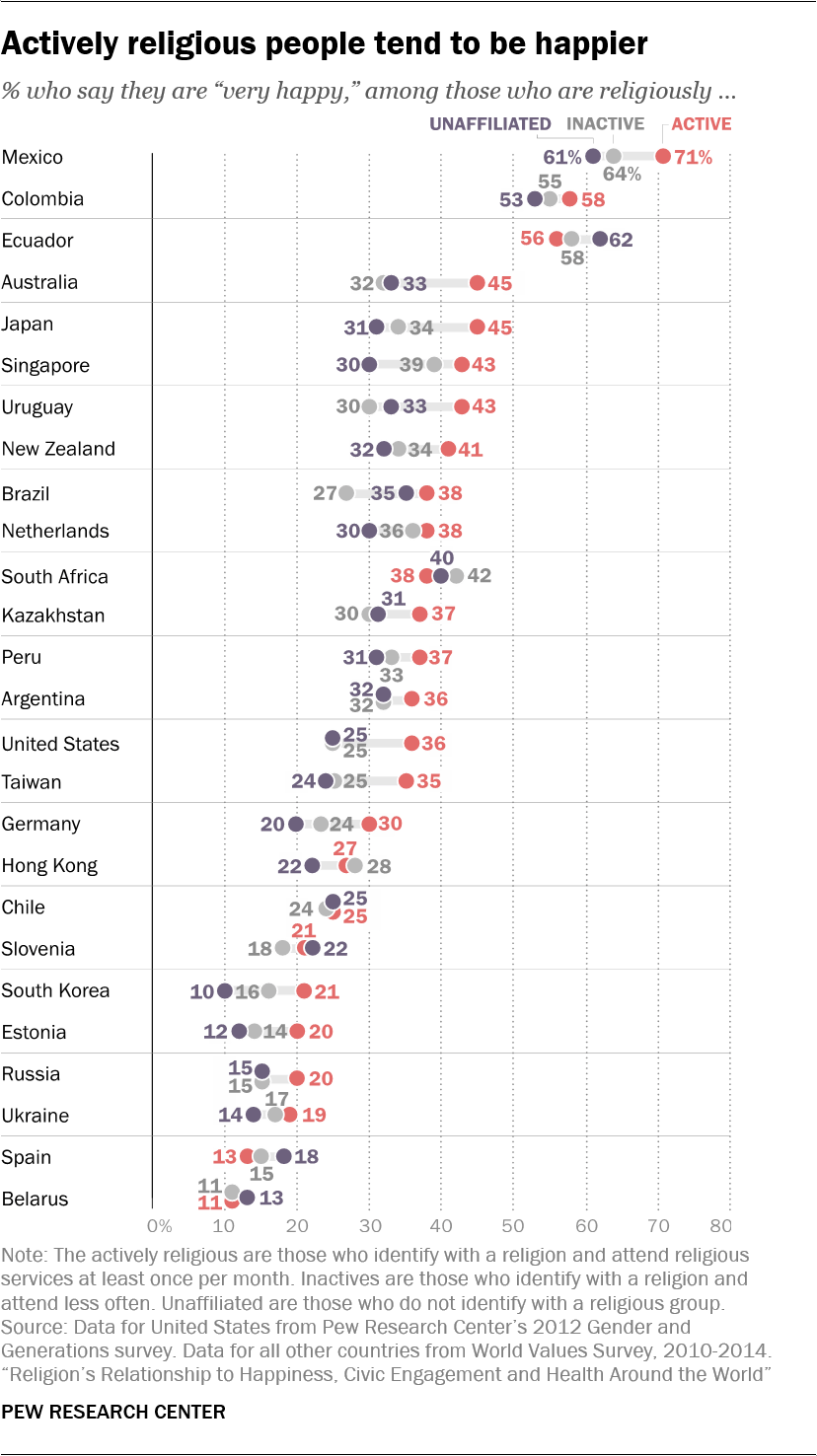

Across 25 other countries for which data are available, the actively religious report being happier than the unaffiliated by a statistically significant margin in almost half (12 countries) and happier than inactively religious adults in roughly one-third (nine) of the countries.

While believers can rely on God to help manage their suffering and endure hardship whether active members of congregations or not, those who regularly attend services have the added support of social connections. Earlier research, Pew pointed out, indicates that friendship is a key factor.

“Those who frequently attend a house of worship may have more people they can rely on for information and help during both good and bad times,” the report said, citing scholars Chaeyoon Lim of the University of Wisconsin-Madison and Robert Putnam of Harvard University. “Indeed, a range of social scientific research corroborates the idea that social support is pivotal to other aspects of well-being.”

More than a decade ago, Putnam looked to involved, churchgoing evangelicals in the US as a counter-narrative to his “bowling alone” trend.

But what about in countries where crime and corruption threaten social structures? Though Mexico, Colombia, and Ecuador have suffered political instability and violence for years, a majority of their residents still consider themselves “very happy”—especially those who attend church regularly.

The three Latin American countries ranked the most content among 24 nations surveyed in the Pew report. In Mexico, Colombia, and Ecuador, a majority of both churchgoers and religious nones identified as “very happy,” double as many as in the US or Germany and triple as many as Spain or Russia.

In the No. 1 country, Mexico, 71 percent of actively religious adults were very happy—the vast majority being Catholic—compared to 64 percent of those who weren’t active in their faith and 61 percent of the unaffiliated. Yet, Mexico has faced climbing murder rates, which reached a record-high last year as clashes with drug cartels grew more deadly.

In Colombia, 58 percent of actively religious adults were very happy, compared to 55 percent of inactive members and 53 percent of those with no religious affiliation. Even a few years after a peace agreement between the government and the FARC (Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia), the country continues to suffer gang violence, guerrilla attacks, drug trafficking, and corruption.

“Colombia is almost in chaos, in a moral state of emergency, and needs to get its values in order,” Viviane Morales, an evangelical politician who ran for president last year, told CT. Urging a position of forgiveness and reconciliation, she said, “We cannot allow political forces dividing the country to manipulate the church.”

Researchers suggested several factors contributing to the correlation between happiness and active faith; religious folks may be happier because they are more involved in their religious community, or they may be more willing to get involved since they’re happier already.

Religiously active adults were also more likely to be “joiners” in other areas of life—they dedicate more time to civic involvement.

In Colombia, where Protestants are more likely than the Catholic majority to attend services regularly, 42 percent of active worshipers said they participate in a community organization outside their church, compared to 39 percent of the religiously unaffiliated and 38 percent of inactive believers. Similarly, 41 percent of religiously active Mexicans belong to other organizations, compared to 36 percent of the religiously unaffiliated and 35 percent of inactives.

The gap is slightly larger in the US, where 58 percent of the actively religious are involved in charity, sports, or labor groups, versus 51 percent of inactive members and 39 percent of the unaffiliated.

The civic participation correlation also applies to voting.

Pew found that “a higher percentage of actively religious adults in the United States (69%) say they always vote in national elections than do either inactives (59%) or the unaffiliated (48%).” The same was true for the actively religious in 9 of the 24 countries polled on this measure.

Some sociologists have linked these voting patterns with the influence of “social capital” among church communities (members are more likely to know others who are voting, be encouraged or reminded to vote, etc.).

Voter turnout by certain groups can shape the outcome of individual races. Many cited the strong showing by black women and dampened turnout by white evangelicals as factors in Roy Moore’s defeat in a special election for Senate in 2017.

But folks who are less likely to show up on Sundays are less likely to show up on Election Day. According to the Pew analysis, the decline in religious affiliation isn’t having as big an effect on society as the decline of religious involvement.

“Regular participation in a religious community clearly is linked with higher levels of happiness and civic engagement (specifically, voting in elections and joining community groups or other voluntary organizations),” researchers wrote. “ This may suggest that societies with declining levels of religious engagement, like the U.S., could be at risk for declines in personal and societal well-being.”