In his early teens, Huang Jian began to withdraw into himself. (Huang and others throughout this piece have been given pseudonyms for their own safety.) A once-happy child, the Chinese middle-schooler gradually became silent. Jian’s father, Huang Yuzhou, blamed the behavioral shift on school “trauma,” a high-pressure environment that sapped his will to learn and engage. Uncertain how to help, the family made a drastic decision: They would homeschool their son, an educational choice currently illegal in China.

“Many Christians, by faith, have decided to give their children a Christian education,” said Huang, a house church pastor in northern China. “They do this in order to prevent their children from losing their faith, and to give them a better education that is in line with spiritual growth.”

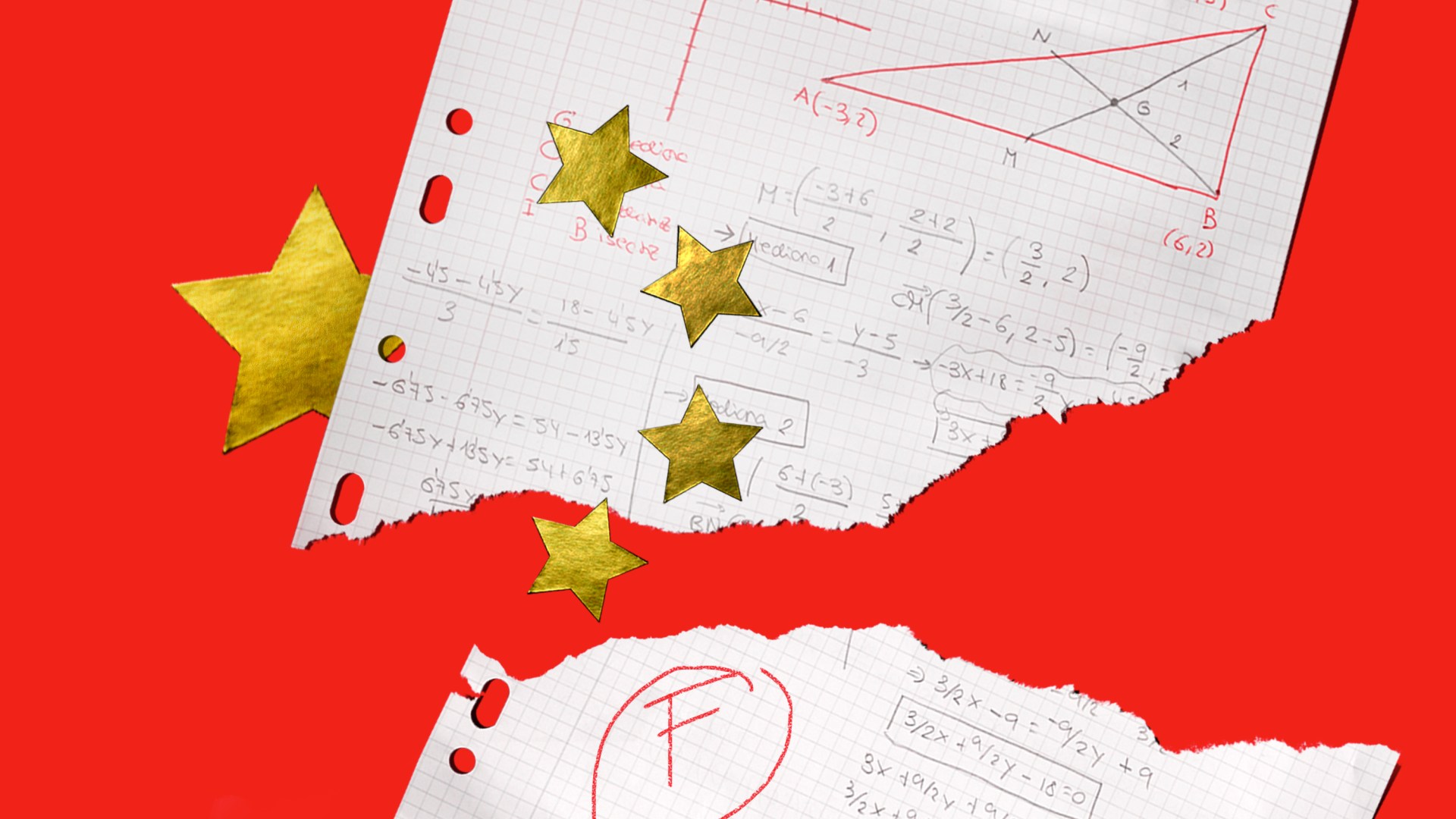

Chinese Christian parents raising their children to follow Christ in a society that opposes their beliefs must confront the question of how to educate and spiritually nurture the next generation without a blueprint. Chinese state school curriculum teaches that God does not exist and compares religious belief to foolish superstition. Many first-generation Chinese Christians struggle in discerning how to pass their faith to their children, especially as they face increasing religious restrictions.

Huang’s son has now graduated. His wife continues to homeschool their youngest child, who is in early elementary school. Huang himself is currently jailed on charges related to his own religious activities. He and his family were inspired to try homeschooling after they learned more about Christian education and hoped it could help their son through his mental health crisis.

“We were watching a child stuck in despair,” Huang said. “It was not until we went down the road of homeschooling that we were able to see a turnaround.”

Lu Jinxiong sent his teenage daughter to study in the United States after she had her own difficulties with an oppressive social environment at school.

“As Christian parents, we have a great burden for the education of our kids,” the Shanghai professional said. “[The government] forces them to go to state school, and homeschooling is illegal. … This is a very big challenge to many of our brothers and sisters.”

Through a series of what they describe as administrative and financial miracles, Lu and his wife were able to send their daughter abroad. While they are grateful for the opportunity, they do not see themselves as a model for other parents agonizing over how to raise their children in the Lord.

“There is really no one true answer on how to face the question of what to do with our children,” Lu said, “because every family is different. Pray that [Chinese] parents will have wisdom on how to face these issues.”

A struggle to educate their kids

Most Chinese families have only one officially sanctioned educational option: state schools. (International and private schools exist, but these are heavily restricted or inaccessible for most families.) Many Christian parents find it painful to place their children in an ardently atheistic system that belittles a life of faith.

The government has long banned evangelism, and religious instruction for minors under the age of 18 is illegal in China. Still, over the past few decades, many officials have looked the other way as Christians found ways to pass on their faith. Some believers have relied on their churches to continue Sunday school lessons. Others, like Huang, fretted that churches were not able to raise up enough pastoral care to assist in spiritual formation for families.

Beginning roughly around the turn of the millennium, more and more Christians across China began to start small church schools to give their children a Christian education. Other families chose to teach their children at home. Both options had become increasingly popular for house church believers, although the space for church schools has constricted in the past few years.

It is difficult to find official figures on homeschooling in China, but estimates placed the number at around 18,000 (a miniscule fraction of China’s 200 million school-age children) in 2013. Still, over the past few decades, homeschooling has grown in popularity as Chinese Christian families in house church circles have learned more about the option.

Opting out of the Chinese system is not easy: Families who educate outside the system through the upper grades are unable to test into universities within China. They must either send their children to college overseas (which is difficult due to both finances and language) or forgo higher education altogether.

These are harsh choices. While many Chinese families aspire to overseas higher education, it is prohibitively expensive. With no remaining domestic options, these decisions shut young people entirely out of higher education. For Chinese Christians, this is sadly nothing new—during the Cultural Revolution, many Christian families lost out on education completely because of their faith.

Last summer, the government announced new regulations governing education in China, further complicating the situation. Much publicity has surrounded the regulations, many of which are aimed at reducing the pressure put on Chinese families to spend extravagant sums on after-school enrichment classes and tutoring as they seek to give their child all the resources they need for future success. Although the expressed aim is reducing pressure on children, these heavy-handed regulations increase the likelihood local officials will deal harshly with out-of-the-box education—such as church schools—within their purview.

These recent regulations plus a general harshening of religious persecution across the country have all but dismantled the education infrastructure believers so painstakingly built across China. Only a few years ago, Christians involved in the education sector estimated the burgeoning movement had as many as 500 schools across China.

Today, believers say the Christian school movement has nearly been suffocated. Small, church-run schools have increasingly been unable to operate since the government turned its attention toward shutting down these schools in the past several years, and among themseles, Christians discuss their fear that homeschooling may be next.

As the public space for church schools continues to diminish, some have been shut down; others have moved completely online—not due to the pandemic, but because of persecution. (Schools across China closed for several months when the pandemic hit in early 2020, but almost all Chinese schoolchildren attended physical, in-person class beginning in fall 2020. Very recently, Chinese schoolchildren have again faced remote school as China again deals with lockdowns due to the advance of the omicron COVID-19 variant.)

Last spring, officials stormed and shut down a Christian school in Anhui Province, arresting four teachers. Two of those teachers remain in jail today; the others were only recently released. Many families from that school have now sent their children back to state schools, and some report their children have been discriminated against and publicly humiliated by their teachers. Parents from the school have also been harassed by the larger community and local officials. In October, police in Jiangsu Province seized a homeschool curriculum salesman and five others associated with him.

Like church schools, homeschooling is also illegal in China. However, homeschoolers have not yet faced the draconian crackdown that church schools have recently endured, although Christian communities are buzzing with concerns that homeschoolers may be the next to undergo systematic pressure.

In the past year, homeschooling parents across the country have been questioned or even detained for their educational endeavors. Last summer, Zhao Weikai, a homeschooling dad in Taiyuan, Shanxi Province, was arrested on charges related to homeschooling his three children. (Because his case has been publicized elsewhere, Zhao is the only name in this piece which is not a pseudonym.) He remains in jail even now. All this is nothing new in China: The change lies in the scope and reach of recent crackdowns, which appear less isolated and more comprehensive across the country, as opposed to a regional focus on a specific group or network.

One day at a time

Those who follow Jesus ought to expect persecution, says Huang, the pastor currently in prison.

“Of course, we, as house churches, are merely a minority in society. We may encounter persecution and are discriminated against and excluded from mainstream society,” he said. “Since God's people are in this fallen world, and since the Lord Jesus Christ is not accepted by fallen sinners, it is impossible for disciples to be exalted above their master.”

Last summer, a prayer update circulated in a group of house church leaders read: “The educational space in Chinese civil society is shrinking dramatically and is about to be reduced to the point of no return. … Christian education is a part of [this trend and] faces even greater difficulties and dilemmas. Lord, we lack wisdom and do not know how to proceed on the road ahead. Please help us!”

Despite the pressure, many Chinese families refuse to be a part of the public education system. Christians are not the only ones with issues with the education system; many non-Christian families also eschew the state school system because of the intense pressure and the lack of emphasis on creativity and original thought.

“The biggest reason I chose to homeschool is freedom,” said a mother of two who lives in Shanghai. Although she is a Christian, she is homeschooling primarily because of frustration with the rigid structure of state schools.

“I do not like the Chinese public education method,” she said. “It is too formulaic and lacks creativity, and it fills up the children’s entire day. There is no time to read, no time to exercise.”

Her husband’s reasons are more faith-based: He prefers homeschooling because it allows them to develop close relationships with and raise their children in a Christian environment.

This mother said she and her husband have not been questioned about their homeschooling, but they have concerns about the future. Still: “Worrying does not help with anything, so we will take it one day at a time. Sufficient to the day is its own trouble.”

Lu, the Shanghai dad whose daughter left China to study overseas, said he does not know how to help young families struggling with these issues in his own community.

His family’s experience is unrealistic for most, even if finances were not an issue; many teens would flounder if they moved overseas alone. And while overseas education may provide for some children, many of these children might choose to permanently immigrate instead of returning to China to build up the Christian community there.

Lu doesn’t doubt the intentions of other Chinese Christian parents who long for their children to know Christ—but he worries that many families seem to be making an idol of their children’s education.

“We do need to warn ourselves,” Lu said. “You may think you are depending on God, but you are really depending on yourself. You may think you are leading your child down a path where he will be influenced by Christ, but it may be a path of self- righteousness. … Bottom line, look to God. Is your child entrusted to you by the Lord?”

E. F. Gregory is the blog editor for China Partnership, which serves, trains, and resources the Chinese house church.