As a kid, I loved combing through the Christmas cards my family received each year. In the days before social media, those annual pictures in the mailbox helped me feel connected to long-distance friends and family.

After my father died, however, Christmas cards served as a reminder of what I’d lost. Photos of smiling, intact families and their cheerful greetings were like salt in a wound. Holidays are always hard for the bereaved. But for me, they added a layer of shame to the grief I carried year-round. As a hurting child, I intuited: My siblings and I were no longer Christmas card material, because our family was no longer whole. For that reason, we never sent another holiday greeting after my father’s death.

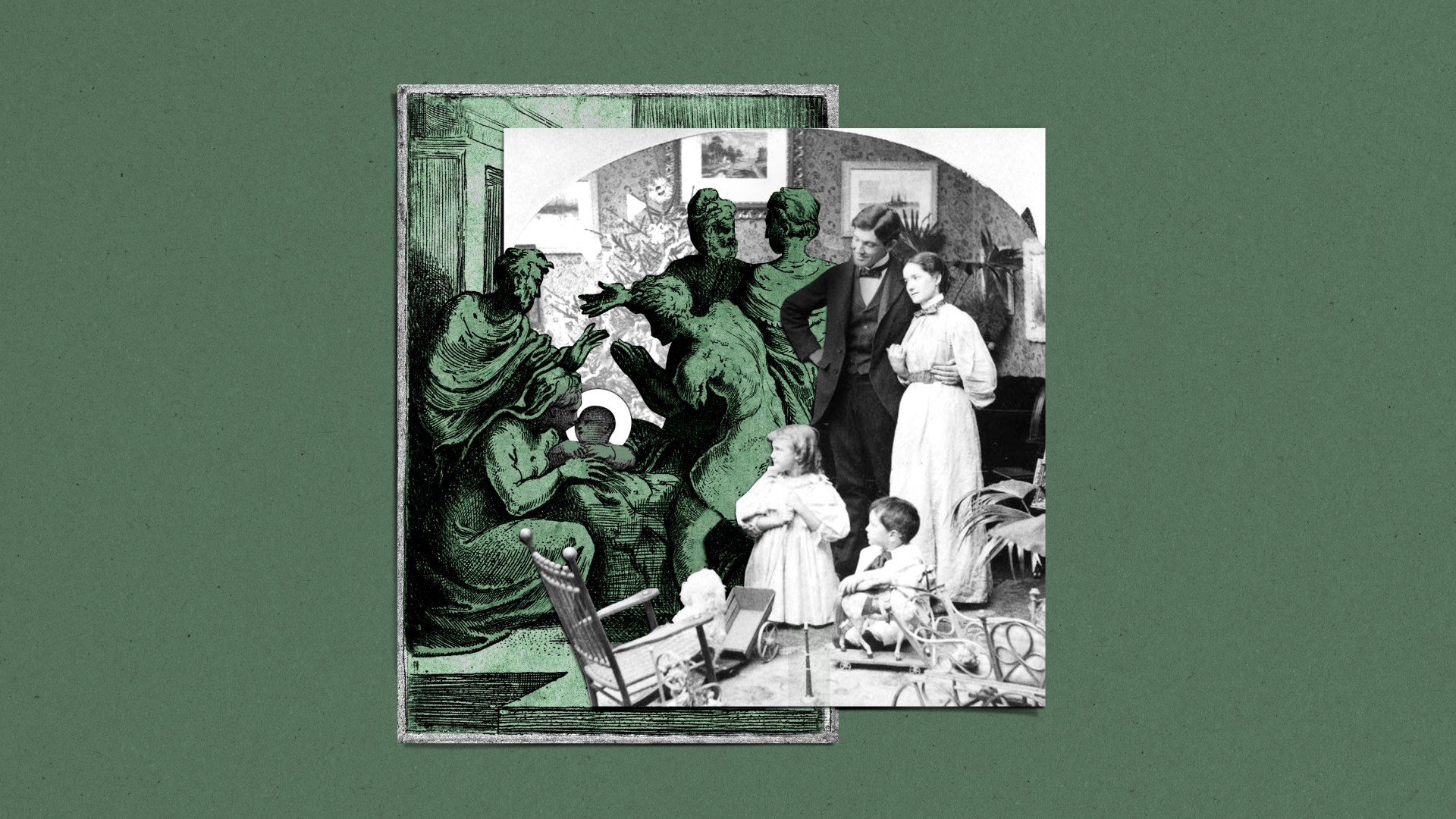

Our cultural fixation with the nuclear family takes on a religious tone around Christmas. We conflate Mary, Joseph, and Jesus nestled in the crèche with our own sentimental notions of family togetherness. We invite families up to light the Advent candles in church. We gather around extended family tables to celebrate. In all the hype, it’s easy to assume that “peace on earth” comes exclusively in the form of a whole and healthy family in front of a Christmas tree.

To be clear, family is a gift from God worth celebrating and supporting. God created the family in part to teach us how to love and be loved. The world needs to see families doing the hard and holy work of togetherness. But as New Testament scholar Esau McCaulley writes, “Our image of family at Christmas—well-decorated, wealthy, happy, and intact—actually sits uneasily beside the gospel of the first [Christmas].”

Jesus’ own family was not exactly Christmas card material. His first “Christmas” (his birth) was not spent in a cozy home with a traditional family but in an outhouse for animals with an unwed mother and an adoptive father. His childhood was marked by the social shame of his mother’s pregnancy (Matt. 1:18–19), the terror of his family’s displacement in Egypt (Matt. 2:13–15), and the realities of poverty (Luke 2:24).

Moreover, Jesus didn’t grow up to have a traditional family himself. He remained single and celibate until his death.

As someone who lost my dad when I was young, I’ve found great comfort in the fact that Jesus’ family story is so complex. From the moment of his conception, Emmanuel demonstrates that he is God with all of us—including the disenfranchised, the poor, the unwed, and the bereaved. The magic of Christmas, of Christ’s nearness, is that it belongs precisely to those who seem excluded from it. Jesus’ own family is proof of this truth.

But Jesus and his parents—named in church history as the holy family—also model for us a new, broader framework that Jesus himself inaugurated. When questioned about his familial loyalties, Jesus taught, “Whoever does the will of my Father in heaven is my brother and sister and mother” (Matt. 12:50). Jesus’ human parents were the first characters in the gospels to demonstrate this obedience.

Mary’s famous “yes” to Gabriel’s message is what made her Jesus’ mother. She consented to God’s will and welcomed him in the most personal, costly, and embodied way. This makes Mary a unique person in salvation history as well as an example for all Christians.

Similarly, Joseph obeyed the angelic command to take Mary as his wife and welcome her son as his heir (Matt. 1:18–25). Joseph’s profound humility and servanthood illustrate God’s countercultural kingdom and remain a prophetic witness for us today.

In their collaborative obedience to God, Mary and Joseph lived together the way that Adam and Eve were intended to. Their partnership represents the beginning of redeemed humanity—the family of God. In other words, the main characters in the Christmas story don’t just give us a model for the nuclear family. They give us a model for the church.

In my own childhood, during and after my father’s death from cancer, the church became to me a holy family—a community that fathered and mothered me in obedience to God. They surrounded and supported my mom as she learned how to raise six children as a widow. Christians fed, clothed, and—for a season—housed my siblings and me. In particular, a handful of men faithfully discipled us as spiritual fathers. Their sustained presence was life-changing for me.

These years later, the influence of those men makes me think of Joseph, a man whose fatherhood was not limited by biology. As Pope Francis writes of Joseph’s ministry, “Fathers are not born, but made. … Whenever a man accepts responsibility for the life of another, in some way he becomes a father to that person.”

Jesus did not come to abolish the family. But he did come to expand it. He came so that we could share in his sonship and sit at his family table. He came to turn strangers into siblings and childless men and women into spiritual fathers and mothers. This doesn’t erase the ache of familial estrangement, bereavement, or unwanted singleness. But it does reframe that ache. And it should reframe the way all Christian households understand the ministry of their common life.

In his book Habits of the Household, Justin Whitmel Earley challenges nuclear families to embrace hospitality as a form of mission.

“We don’t care for our household because our responsibility is to our bloodline and no one else—that is a cloaked form of tribalism,” he writes. “Rather, we care for the family because it is through the household that God’s blessing to us is extended to others.”

As Christmas approaches, we can reflect on the small, nontraditional household that extended God’s blessing to the world through the birth of Christ. And we can marvel at how that household expands to encompass each of us.

I marvel at that truth every time I look at an icon of the holy family that sits on my desk. It was given to me by a friend when I was pregnant, and it usually inspires me to pray for my own ministry as a mother to three children. But occasionally, I think of it as a family portrait in which I’m somehow mysteriously present, as well.

To be clear, Jesus’ human family was and is distinct. But his spiritual family includes those who are born “not of blood nor of the will of the flesh nor of the will of man, but of God” (John 1:12–13, ESV). This family is made from every tribe and language and nation, and its destiny is eternal fellowship with the Father (Rev. 7:9–10).

One particularly difficult Christmas a few years ago, when I was grieving the sudden loss of my brother, I discovered another image that features the holy family. In a drawing called “Mary and Eve,” Eve is naked, sorrowful, and entangled by the serpent at her feet. Mary is pregnant, dressed in white, and stepping on the head of the same serpent.

That image has become a personal sort of Christmas card. It reminds me not to look for ultimate fulfillment in any iteration of the nuclear family but to entrust myself and my loved ones to the Son who makes us all sons and daughters.

In the face of profound loss and enduring loneliness, this unbreakable family lineage sustains us. It teaches us how to live together as a community of brothers and sisters until the Lord comes. And it embeds our grief in a larger hope of the reunion—and resurrection—that awaits.

Hannah King is a priest and writer in the Anglican Church of North America. She serves as an associate pastor at Village Church in Greenville, South Carolina.