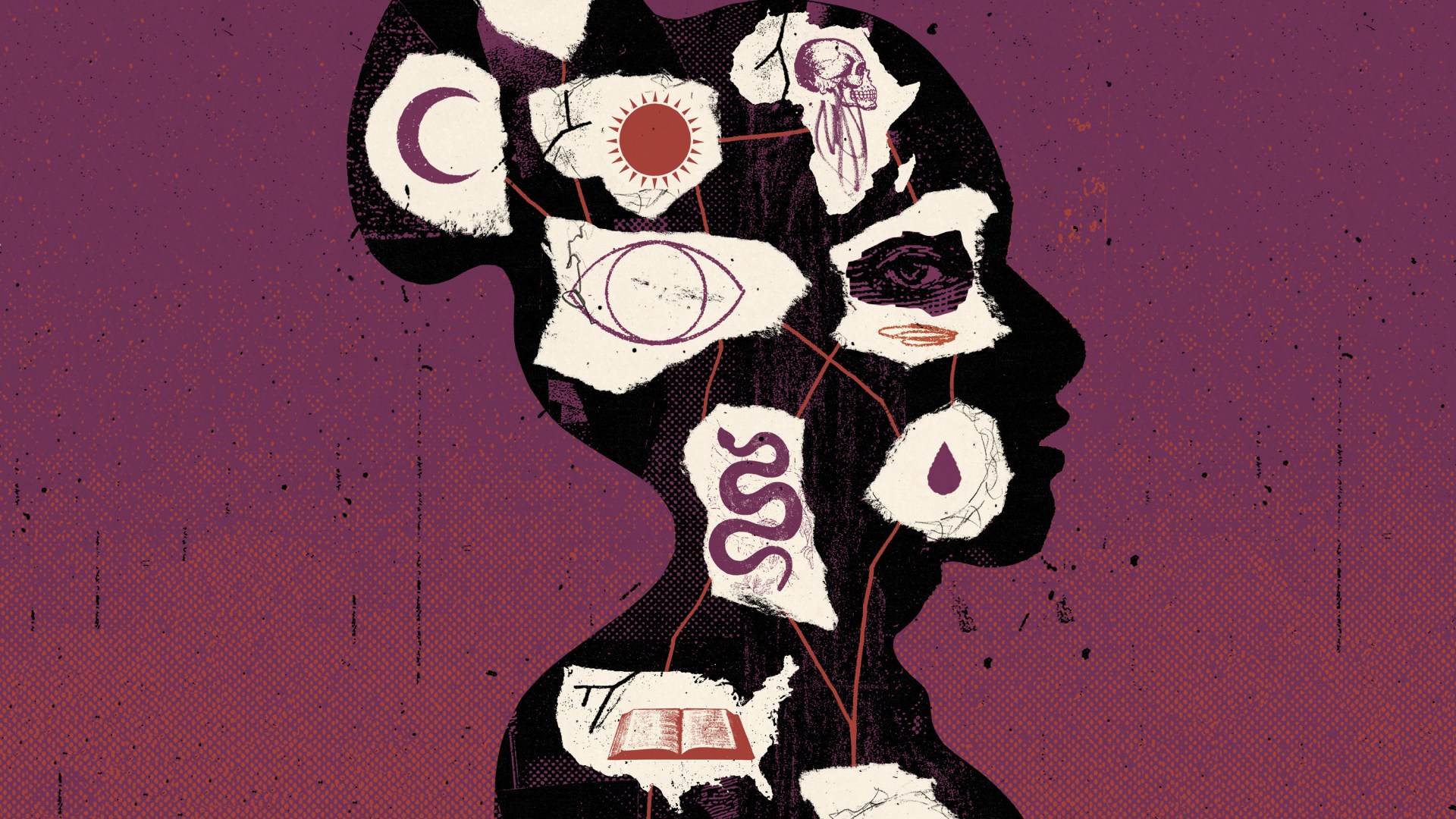

By the time Day Sibley decided to embrace Ifa, a divination practice from the Yoruba people of Nigeria, she had long been on a search for identity that she could never quite fulfill.

She grew up in a nominally Christian home in Las Vegas, where her family sometimes talked about God and went to church only on holidays. As a child, she could tell you that Christ died for our sins, but what exactly that meant was unclear to her.

As the years went by, Sibley faced bullying at school, a breast cancer diagnosis for her step-grandmother, and the perennial question about suffering: Why do bad things happen to good people? She inquired of those around her only to hear, essentially, “That’s how life is.” At the age of 12, Sibley became an agnostic, doing “what I want, when I want,” as she put it.

For more than a decade, life stayed that way. Christian friends came along during a brief period when Sibley was searching for God. But their fellowship quickly disintegrated when they became more devoted in their faith and she didn’t. She was wrestling with her identity on several fronts, including sexually and racially. After the killing of Trayvon Martin in 2012, Sibley became involved with the Black Lives Matter movement.

But despite her activism, she didn’t feel comfortable being Black. Some of her peers had labeled her cultural interests and the way she spoke as “white,” which left a lingering feeling that she needed to prove her identity. All of this pushed her closer to African spirituality. But the catalyst came in 2017 when she landed in the hospital after eating a marijuana-laced brownie (thereby discovering she was allergic to pot).

While in an unconscious, coma-like state for a day, Sibley said she heard a woman’s voice that resembled her grandmother’s say, “You only have one life.” It sparked curiosity. A few months later, she was driven by a desire to return to her roots to purchase a voodoo doll while traveling in New Orleans.

At home in Vegas, she found a local Ifa priestess and started the initiation into the West African religion. “I thought this would be the answer,” Sibley said. But soon enough, she came to find out that it wasn’t.

The quest to find a spiritual heritage that predates colonialism and the transatlantic slave trade has led many Black people to embrace traditional African religions such as Ifa or others from across the African diaspora including Cuban Santería, Brazilian Candomblé, and Haitian Vodou (which blends in Catholic imagery and is closely associated, but distinct from, Louisiana Voodoo).

The practices tend to be transactional, with adherents making offerings of libations, money, or other goods to appease spirits or to receive guidance and their hearts’ desires. Though the religions are not new, they have proliferated—particularly among Black women—in recent years. Social media has played an outstanding role, as has the growing political and racial polarization and the rise of religious deconstruction.

In the US, African spirituality is one of several Black conscious communities that range from the Nation of Islam and Black Hebrew Israelites to Kemetic spiritualists promoting ancient Egyptian religious practices. Proponents of these communities emphasize ethnocentric religious rituals and often tell half-truths about the Christian faith, leveraging the true harm done by white Christians against Black people throughout history while obscuring Christianity’s deep history in Africa.

I have encountered advocates of these movements in my personal life, particularly while doing evangelism in Atlanta and Brooklyn. My social media feeds—which have accurately detected that I’m a Black woman— periodically also serve me this kind of content.

These practices have a strong appeal because Black people have had their identity stripped and their dignity tarnished, most often by a twisted version of white European Christianity that lacked Christ.

Given the misuse of the Bible to justify slavery and the whitewashing of Christianity to portray a blue-eyed Jesus, it’s understandable why many initially have reservations. The problem has been compounded by centuries of racial injustice, recent killings of unarmed Black people, and evangelical support for President Donald Trump, who dabbles in racially inflammatory rhetoric.

While the Black church has functioned as a balm over racial pain for centuries, its theology has been contested by those who view Christianity as a religion “forced” upon Black people.

Many of these objections have been around for decades. But “the game has changed” with the rise of the internet and social media, which allow falsehoods about Christianity to have a longer lifespan, wrote author Eric Mason in Urban Apologetics: Restoring Black Dignity with the Gospel.

Adherents of Black conscious communities advertise their practices as a source of pride, evidence of an uncolonized mind, and a way to reclaim one’s roots. There’s not good data on how many Black people have embraced each practice, but one Pew Research Center survey conducted six years ago found that one in five Black adults pray at a home altar or shrine at least a few times a month.

Black Americans who have turned to these practices come from a variety of different spiritual backgrounds. Some, like Sibley, began as agnostic. Others left the Christian faith after experiencing church hurt, doubting what they believe, or having disagreements around sexual ethics. Some have left Black churches because they’ve seen hypocrisy there, said Lisa Fields, the president of an apologetics organization called the Jude 3 Project.

A similar trend is happening in the United Kingdom, where Fields has given talks about the topic. She told me most people aren’t devoted to one religion. They’re choosing a hodgepodge of spiritual practices, from Ifa to crystals to Kemetic science, to construct their own faith. “People don’t want to be tied down to any particular set of beliefs,” Fields said.

Still, there are general trends. Urban religions like the Nation of Islam or the Black Hebrew Israelite movement have always appealed more to men. Women, meanwhile, have tended to gravitate toward African traditional religions, where they’re often cast as divine.

In these communities, terms like queen and goddess often fly around, giving comfort and validation to Black women who feel undervalued in their communities and in broader Western culture. Some Christian women even fall into the practices out of a false belief that such things will provide answers to social ills in a way that’s compatible with Christianity.

In early 2020, Sibley decided to take charge of her spiritual practices after having a bad experience at the home of an Ifa priestess. The woman, Sibley said, was ripping off her clothes and yelling at other initiates who were attending a spiritual celebration.

Sibley went home and decided to conduct her own ancestral veneration, mixed with tarot and Neopaganism. She said she would ask for things during rituals like romantic relationships, friendships, or a new job. Sometimes she didn’t get what she wanted. Sometimes she did but it was short-lived. “I noticed they give you what you want but not what you need,” she said.

Sibley has since come to believe she was unknowingly communicating with demons. Over time, she asked for a higher-paying job and other things but noticed the spells she used were no longer working. She also began having nightmares every night and felt she was being attacked spiritually by her former priestess, whom she often saw in her dreams. Sibley then decided to retaliate with her own spells.

When things didn’t get better, she confided in a Christian friend, who took her to a local Pentecostal church. The pastor there prayed for her.

Then, she said, he conducted an exorcism on her. She accepted Christ into her life.

When she got home, she began throwing away everything she used for witchcraft. Sibley said she even teamed up with her friend to bury some of those items in the Las Vegas desert, but when the two were unexpectedly surrounded by a swarm of flies, they dropped everything and left.

She began praying to God about her life and her family. Bad things continued to happen: Two family members got into a car accident. Her insomnia affected her job, and she was fired from her role.

But she kept praying, and slowly things got better. Her newfound faith created distance between her and some old friends, and God opened the door for new Christian friends and fellowship. She found a new job as a substitute teacher. And her parents began warming up to the Christian faith. While her prayers don’t always get answered in the way she wants, she has discovered God’s path is better than her own desires.

“I am very blessed,” Sibley said. Some people die under those false practices, she added, but “it made me bolder in Christ.”

The glorification of African religious practices religious practices isn’t found only on social media. It’s also expressed at the pinnacles of pop culture.

Ryan Coogler’s hit movie Sinners, released in 2025, offered a warm depiction of Hoodoo, an African American folk religion related to Ifa. Some African spiritualists rejoiced last year when actor Michael B. Jordan seemingly revealed during a media interview that his middle name was given by a babalawo, or a priest in the Ifa religion. Pop star Beyoncé often incorporates references to African spiritual traditions in her songs and music videos.

“People have interpreted demonic teaching in many ways in a beautiful, elevated art form. So it doesn’t seem dangerous and incompatible with the faith,” said Sarita Lyons, a prominent Bible teacher and author of Church Girl: A Gospel Vision to Encourage and Challenge Black Christian Women.

Writer and influencer Jackie Hill Perry has warned her followers to exercise wisdom and discernment when consuming different art forms, including Beyoncé’s music. But serious Christian voices issuing those warnings have been few and far between.

Lyons said Black Christians in particular can find themselves in a tenuous place trying to maintain a sense of solidarity and refrain from criticizing another Black man or woman. But we can support our brothers and sisters without sacrificing Christ, she said. “The Christian is called to be serious,” Lyons added. “We aren’t called to be tightrope walkers. Sometimes, we have to turn our backs on the things that the world applauds.”

Lyons grew up Christian but practiced the Yoruba religion in college some decades ago. At the time, she said she was looking for something that would rescue her from white supremacy and affirm her identity. What she found was a “lifeless life- boat” that appeared to have rescuing power but failed to deliver her.

These days, Lyons is a well-known urban apologist making a strong defense of the gospel while paying attention to cultural context. For anyone interested in stepping into this space, Lyons says it’s important to talk about these harmful practices without demonizing everything African.

While every culture on every continent contains aspects that don’t glorify God, the Bible should serve as a guide in sorting through what to confront and throw out, what to reform or clarify, and what to keep.

For Bethaney Wilkinson, letting the Bible dictate what to throw out meant burning all her tarot cards in the tradition of the sorcerers in Ephesus who brought their scrolls together and lit them on fire publicly (Acts 19:19). The backyard bonfire came a few years after she started practicing alternative spiritualities, mixing tarot with African religions and spiritual breathwork.

Like Sibley, Wilkinson’s religious journey began in childhood. As a Black girl in a small town in Georgia, she too felt racially disoriented. She received good grades in school and was teased by her peers as an “Oreo,” a disparaging term for a Black person who displays traits or preferences typically associated in US culture with white people. But comments about her hair texture and the experiences she had with some white adults, who seemed hesitant to allow their kids to come over to her house, made her acutely aware she wasn’t white.

When she was a teenager, she started attending a local church with her family and became a Christian. Soon after, she left her small town and attended Emory University, where she studied African American studies and sociology. That and her involvement in InterVarsity Christian Fellowship gave her a deeper understanding of race, racial justice, and the racial reconciliation conversations taking place within evangelicalism.

After graduating in 2012, Wilkinson started teaching racial justice seminars with a racially diverse group of people at evangelical churches in the Atlanta area. Most churches welcomed the message, but some congregants seemed suspicious. The work, combined with the racial and political divides in the country, eventually became too exhausting.

The evangelical world, Wilkinson felt, brought too much pain and disappointment. Polarization worsened and the healing she expected was nowhere to be found. She started deconstructing her faith four years later and began working on diversity initiatives at a secular nonprofit group.

Looking back, she said, she believed in Jesus and knew she had real experiences with God. But after college, “I probably had given myself over more fully to secular activism” and was being discipled by it, she said. “It became more about how we’re impacting the world and what’s our impact for God, and not true intimacy with Christ.”

A few years later, Wilkinson had surgery to remove some fibroids. That, coupled with other personal challenges she was facing at the time, sparked her interest in well-being. She followed a wellness guru on social media who dabbled in New Age and African spirituality and attended a Black women’s retreat in Arizona that focused on healing the womb. There, she saw people doing rituals such as ancestral veneration and New Age full-moon observances.

When she returned home, Wilkinson started practicing tarot. She had read it was an African practice but later found out it came from Italy. Other practices soon followed. Then, “my life went to s—,” she said.

Though her consulting business was booming, Wilkinson said she became dependent on alcohol, developed a skin condition that dermatologists couldn’t identify, and experienced a “deep, deep emptiness.” Her marriage also felt dysfunctional.

Around the same time, her husband started attending an Orthodox parish near their home in Georgia. She visited the church once to support him, but she was opposed to the idea of joining a congregation, especially an Eastern Orthodox parish that believed religious authority rests solely in the hands of men. The emptiness, however, felt untenable. So one day she prayed: “Jesus Christ, I don’t know what’s happening, but please help me.”

As she attended more services at the church despite hesitations, God slowly began to answer that prayer. The more she went, the more she felt at peace and began to enjoy the spiritual life of the congregation.

“God started to chip away at my fears and my anxieties about the Christian faith while also gently humbling me,” she said.

Wilkinson eventually burned her tarot cards, deleted her astrology apps, and devoted her life back to Christ. She came to see that dignity and justice for Black people is indeed in the heart of God. But the only way to achieve true social and racial healing is in the “radical surrender to the way of Christ, which includes repentance, forgiveness, and loving your enemies.”

After a lengthy catechumen process, she was received into the parish last April as a member. During that time, her skin healed and she overcame her dependency on alcohol. She said her marriage is better than it’s ever been.

“I’m not saying that life is perfect,”she added. “But it is dramatically better than it was when I was pulling tarot cards.”

Correction (January 30, 2026): A prior version of this article said “stepmom” where it should have referred to Sibley’s step-grandmother. It also referred to Wilkinson as “Wilkerson” in one paragraph.

Haleluya Hadero is the Black church editor at Christianity Today.