Several episodes in season 5 of The Chosen begin with Jesus and the apostles gathered for the Last Supper, a Passover meal. In a ritual familiar from my Jewish childhood, they recite a traditional Passover song in Hebrew, “Dayenu” (“It would have been enough”).

It’s about God’s miracles during the events described in Exodus. An English translation goes like this: “Had he brought us out of Egypt but not carried out judgments against them, it would have been enough. … Had he split the sea but not carried us through on dry land, it would have been enough.” And so on, until the building of the temple.

Our minds reel against such statements. Had God at the Red Sea not carried the Israelites through, they would have been dead. But the idea is that we should have complete confidence in God’s sovereignty. He is God. We are not. We are to be grateful for everything God does.

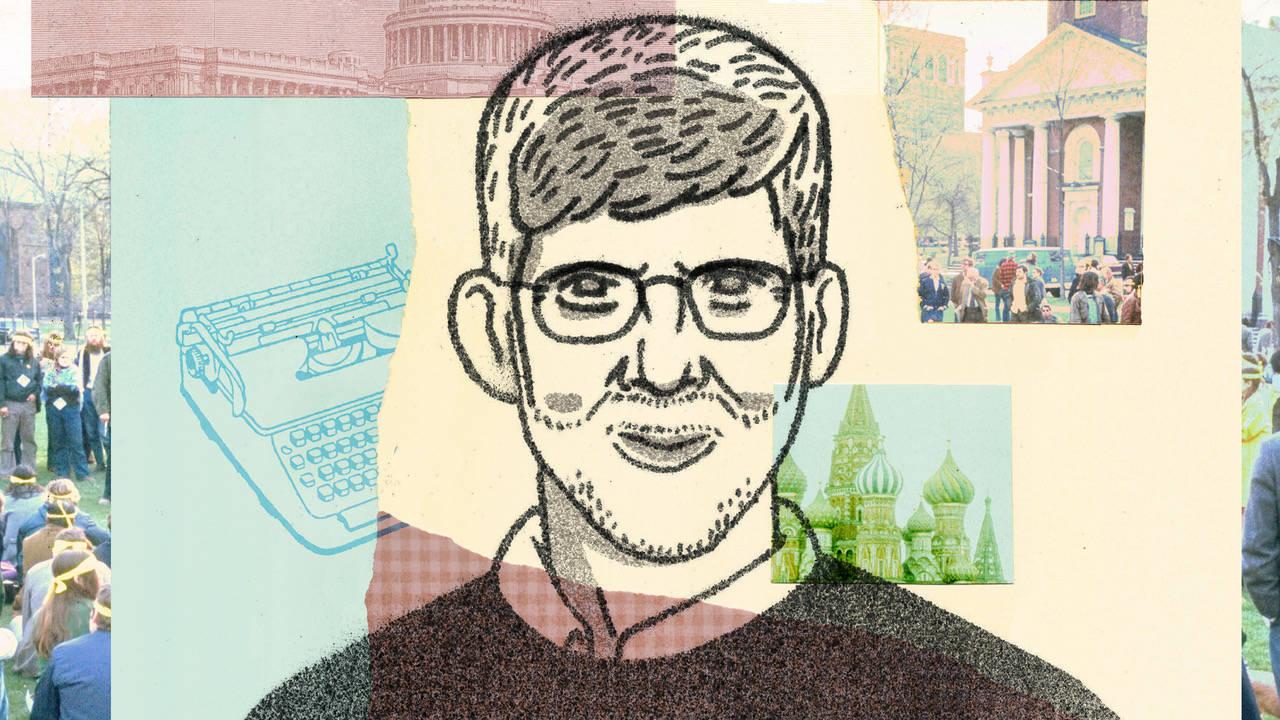

Testimonies often center on a brief time of transition to faith in Christ. True enough, but looking back from age 75, I also see a long dayenu and would like to tell the rest of the story, a lifelong one, in 2,000 words that could be reduced to one: gratitude.

First, the short testimony. It began in 1971 when I graduated from Yale. Professors there had seeded my mind with Marxist ideas, but the soil was the Vietnam War and my own arrogance. The day after graduation, I began bicycling from Boston to Oregon. Ten weeks later I started work at a small newspaper and quarreled with the local political and business leaders, since nothing short of being a know-it-all ideologue was enough for me.

In 1972, I joined the Communist Party USA, took a Soviet freighter across the Pacific, and traveled to Moscow on the Trans-Siberian Railway to be a foreign correspondent. That didn’t work out, so then came reporting at The Boston Globe, Russian language study at Yale, and enrollment at the University of Michigan with the intention of becoming a professor. Nothing short of indoctrinating students in Marxism was enough for me.

But on November 1, 1973, All Saints Day, at 3 p.m., everything changed. In my off-campus room, I was reading Vladimir Lenin’s essays on socialism and religion. He writes, “We must combat religion—this is the ABC of all materialism, and consequently Marxism.” I suddenly thought, What if Lenin’s wrong? What if God exists?

Not sleeping, not drinking or drugging, not hallucinating, I sat in my red chair by my bed for eight hours and could not shake that thought. At 11 p.m., I rose and until 1 a.m. walked the cold, dark university campus. No longer wanting to combat religion, no longer a materialist, I tore up my Communist Party card three days later. But other than a vague sense that God exists, what did I believe?

In 1974, I was required to gain a good reading knowledge of a foreign language in order to move toward that title of nobility, PhD. My bookcase “happened” to contain a souvenir copy of the New Testament in Russian. Good for reading practice, I thought. Five chapters in, the Sermon on the Mount grabbed me. All the Marxists I knew believed in “two eyes for an eye,” but Jesus spoke of loving our enemies and turning the other cheek.

Later in 1974, to meet another requirement, I had to teach whatever course the faculty assigned me. My lot was early American literature. Forced to cram by reading Puritan sermons, I learned that God mercifully saves sinners like me, regardless of all the commandments we have broken.

In 1975, one more requirement: Develop and teach an undergraduate course. Mine was a seminar on Westerns such as High Noon. In them, heroes had to risk their lives for what they believed. I knew I should do the same. Books by Christian existentialists Gabriel Marcel and Walker Percy also were instructors. Still, I knew no Christians and the libertine college-town atmosphere of Ann Arbor, Michigan, had its appeals.

Then Susan—a smart, pretty, and kind agnostic—came into my life. I realized I felt what the protagonist in a novel Percy would publish four years later described: “Am I crazy to want both, her and Him? No, not want, must have. And will have.”

Susan stood by me as I finished my dissertation and survived the fierce opposition of a progressive professor. In 1976 she and I married and moved to San Diego for my teaching job at the state university there. Feeling a pull to go beyond spiritual groping, I looked in the yellow pages for a nearby church. A Conservative Baptist around the corner appealed—not Marxist, and Christians still baptized, didn’t they?

The pastor preached the same simple sermon week after week: Ye must be born again. No intellectual razzmatazz. It was exactly what we needed to hear. Soon, we both admitted our need, professed faith in Christ, and lived happily ever after.

This is true enough in one sense. Susan and I will mark our 50th anniversary in June. That’s the major project of my life and what I am proudest of, particularly because a lesser part of it is my doing. Glory to God. Gratitude to Susan. Thankfulness for our four children and seven grandchildren.

But the long testimony involves what we learn after conversion, as God teaches us.

God used the writings of many former Communists in my journey to Christ. I carried into my Christian life Whittaker Chambers’s view of the world, a view that saw a titanic struggle between the West and Communism, between freedom and slavery. I was frustrated that many people in the US didn’t understand the stakes.

I was right to oppose the left, but in my immature understanding of the Bible I took metaphors about spiritual warfare and applied them to the material world.

Falling back on Marxist-like thinking about how to get things done, I embraced “Christian reconstructionism” because it offered a God-ordained blueprint for government. Theonomists such as R. J. Rushdoony and Gary North seemed serious about pursuing it in American life.

Their books in some ways prefigured the current “Seven Mountains” thinking influential among Christian allies of Donald Trump. North was a little like Lenin, who rejoiced when his Bolshevik ideas took root among some peasants. He excitedly told me in 1983 that his hyper-Calvinist ideas—gain power, pass laws to restore morality—were infiltrating Pentecostal ranks.

My dalliance with theonomy took place while I desperately needed church community and found it via correspondence courses in those pre-Internet days. My “community” was like-minded theonomists who lived thousands of miles away. Puffed up with knowledge, I criticized ordinary pastors and Christians I met in real life. And yet, the theonomists I knew were unloving. Petty disputes permeated their ranks. Perhaps I had the same disease.

As a Christian conservative, I faced hostility from fellow professors at The University of Texas at Austin and attributed it to theology and ideology—but some of it was on me because I disliked faculty meetings and rarely socialized with people in my department.

God didn’t leave me in my pride, though. In 1989, I took a leave of absence from the university and moved with my family to Washington, DC, to research at the Library of Congress what became two history books, one about poverty and the second about abortion.

During those two years, two things happened. First, I learned about the incredible, often-lost history of Christians who helped the poor or women contemplating abortion. Just like me, they read the Bible and asked what difference the gospel should make. Instead of talking primarily about political change, they became doers of the Word. They set up a great diversity of organizations and ministries to help single moms, orphans, immigrants, and homeless people. Accounts of their work changed me.

Second, while there, my family and I attended Wallace Memorial Presbyterian Church, pastored by Palmer Robertson and Bill Smith. Week after week we heard biblical preaching that penetrated my prideful soul. Robertson especially took the time to challenge my theonomic understanding that the laws governing ancient Israel should govern America. He taught that we live in a modern Babylon or Rome where many people worship false gods. We are called to show people a different way to live but not to smash their idols, which the ancient Israelites were commanded to do.

We moved back to Austin. Those two history books came out in 1992. Neither sold well, but some influential Republicans read The Tragedy of American Compassion and passed it to others.

Newt Gingrich read it just as he became speaker of the House, the first Republican in that position in 40 years. Cameras and microphones recorded his every gesture and word. In his introductory speech to Congress in January 1995, and for months thereafter, Gingrich commended my research and ideas on helping the poor.

That opened an opportunity to travel the country, learning about existing Christian poverty-fighting organizations and publicizing their work. Just like their forebears in the 18th and 19th centuries, these believers had read the Bible and had seen how God cares for the poor—and that we should do likewise. It was a fruitful period, because that message seemed to resonate with ordinary people and with politicians in Washington.

It was a heady time for me personally—and a kindness that it hadn’t happened a decade earlier, when it might have shipwrecked my faith. I went to fancy dinner parties, hit the talk-show circuit, and met with politicians of all stripes. Many seemed serious about passing a charity tax credit that would encourage on-the-ground efforts. It even seemed as though some Democrats would get on board, but amid debates about decentralization and deficits, the tax credit idea died. But the on-the-ground movement lived.

Back in Austin, George W. Bush and I talked and bonded about Christ and baseball. He made “compassionate conservatism,” a phrase from my book, his campaign theme when running for reelection as governor in 1998 and president in 2000. His positive vision of a “culture of life” and “armies of compassion” seemed popular with an electorate that had suffered through years of tawdry Beltway scandals.

But hopes that compassion would translate into a winning political program died after 9/11. The Bush presidency became a wartime presidency. The failure of compassionate conservatism cured me of any remaining love for politics, and my temporary fame was enough for a lifetime. Dayenu.

Looking back, it’s clear that from 1973 to 1976 I rode a slow train from Marxism to Christ, but the testimony does not end there. A 1989–1995 slow train transported me from theonomy to a Christ-centered view of social change: “one by one from the inside out.” That’s where I have been since.

What I saw around America also left me with some confidence that our country will survive hard times. We need more than ever a journalism that watches and listens rather than pontificates. Sadly, those who turn barstools into pulpits seem to have the largest megaphones.

That brings me to another big cause of my lifetime—Christian journalism. In 1986, Joel Belz pioneered a new publication, World. It lost money for six years. I was at a board meeting in 1992 when two members looked at the balance sheet and proposed euthanizing the magazine. In my one It’s a Wonderful Life moment, I sputtered, “You can’t shut it down. Christian journalism is crucial.”

The board agreed to keep World alive, but only if I became a hands-on editor (and soon after, editor in chief). We made the magazine livelier and grounded in reporting. During the 1990s, the magazine went from 10,000 to 100,000 subscribers.

In the next two decades, the journalistic and the personal became interwoven as Susan and I taught journalism seminars in our home and had interns living with us for two months at a time. We covered refugees and other immigrants sympathetically. We ran features showing how crime hurt the most vulnerable citizens. We regularly covered abortion, but not primarily as a political issue. We ran profiles of people who lived self-sacrificially and investigative stories about leaders who sacrificed others. We believed in truth and fairness and tried to avoid the kind of sensational language that seeks to inflame.

American politics changed, and so did the business side and board of World. On November 1, 2021, All Saints Day, I resigned. Of “retirement age” but not ready for golf. I did some freelance writing, finished work on several books, devoted more time to service as a church elder, and took regular dog walks with advice-seekers. In good health, with a loving wife and extended family, dayenu. It was enough.

In April 2024, Tim Dalrymple, at that time CEO of Christianity Today, called me: Would I be a consultant? That yes was easy. At the end of 2024, when CT asked me to work full-time, the opportunity to have one last rodeo was appealing. I began serving as executive editor for news and global. One of my first acts: Encourage CT to give out its first annual Compassion Awards. Dayenu.

Last fall, Russell Moore and other leaders asked me to become editor in chief so Russell could devote more time to the writing and speaking he loves and excels at. This new turn in my long calling was exciting and unexpected. When I edit, I feel God’s pleasure. What comes next, I don’t know. But I do know I’m in good hands, the best hands: Jesus forever and Susan for as long as we both shall live.

Marvin Olasky is editor in chief at Christianity Today.