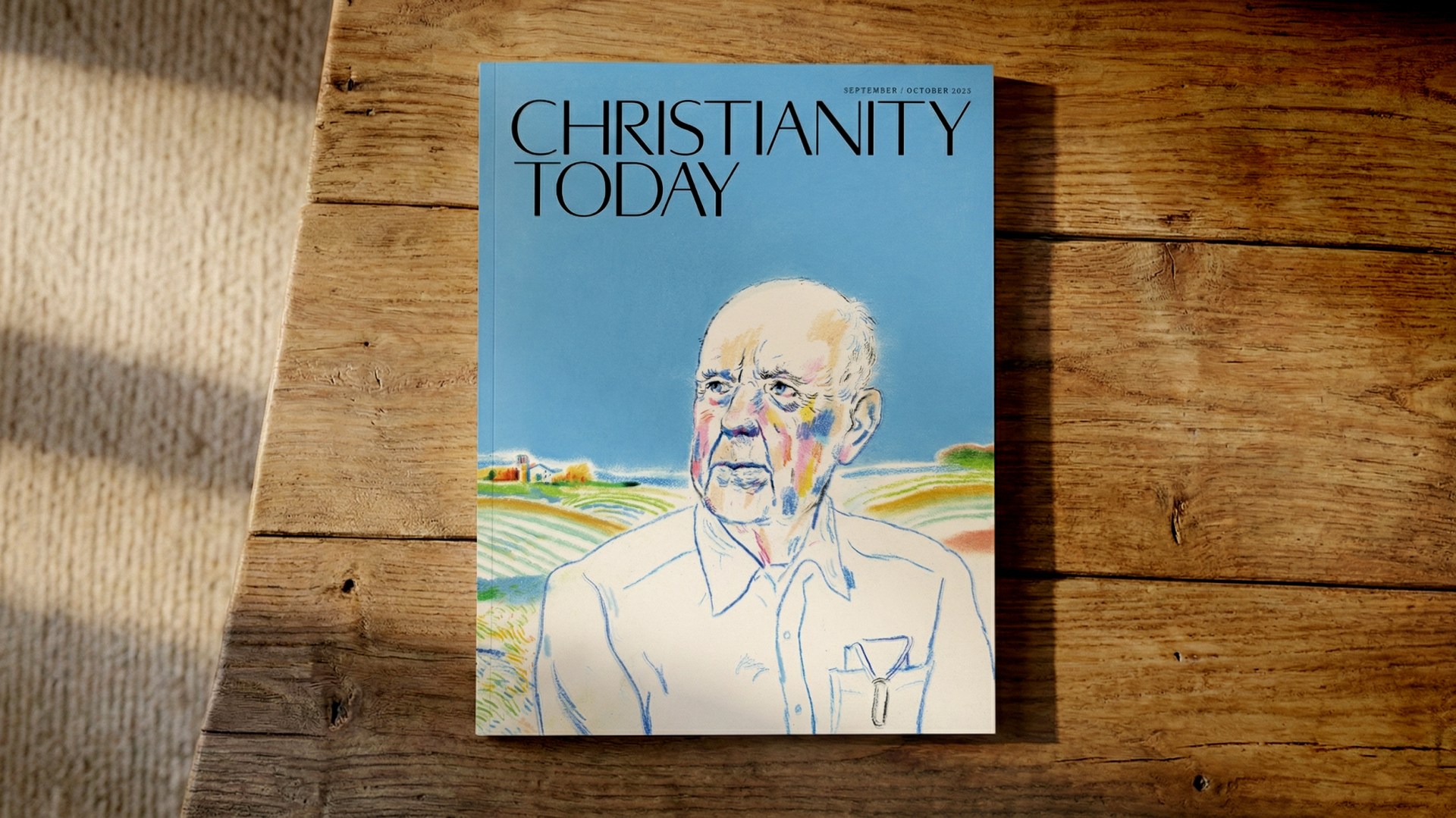

Sometimes being an editor is like being a sculptor. That’s how it felt to work on Isaac Wood’s essay “Faith After the Flood” (p. 42) in our September/October 2025 issue. Isaac, a reporter living in East Tennessee, initially turned in thousands of words about how churches responded to Hurricane Helene, his writing brimming with quotes from volunteers and descriptions of donated food, clothes, and gas, as well as reflections on how service might be a way to get disillusioned young people back in the pews.

In email and phone conversations stretching across months, Isaac and I talked through how we might cut back and organize all this material to best convey its message (while keeping a great line about a possum) plus allow him space to tell his own story of belonging to a Johnson City church.

When you read an essay in CT, know that what you’re encountering is never a first draft. It’s a collaboration between not only the writer—who gets most of the credit, of course!—but also editors, our design team, and copyeditors, all believers working together to narrate a particular instance of God’s work in the world.

Kate Lucky, senior editor, features

It Was ‘Good,’ Not Perfect

I wonder why John Swinton takes issue with the concept of “an assumed norm of bodily or cognitive integrity.” If we believe God designed the human body, it follows that he intended it to function in a certain way and that departures from that design represent dysfunction. Of course it does not diminish the value of a person made in God’s image to recognize that in this fallen world, where creation is indeed groaning, people may live—and thrive—with limitations that God never intended them to confront.

The real issue in the encounter of the author’s friend with the well-meaning elder is not whether disability was part of human existence from the beginning but whether we in the church can indeed honor and receive those who suffer from it without the assumption that God now intends his people to live free from the effects of the Fall.

Beth Webster, Turlock, CA

John Swinton’s essay brought to mind my mother and father. My mother in her final years suffered from dementia. Initially, though she could no longer talk, when she saw a resident in need, she sought to comfort them. For the most part, my father was with her every day. For a while, he was able to take her for drives in the country. He walked with her (later wheeled her) on the sidewalks outside the facility and along the hallways in the adjoining hospital. He played orchestra videos and brushed her teeth. Together, they delivered hospital patients’ mail. When she died, it was not a blessing. He missed her terribly. They were married 60 years, and now their relationship and half of who he was had been ripped away.

After my mother died, young women on staff told our family that my father’s love and dedication demonstrated how they wanted their own marriages to be. It was a hard time, but to the end, the image of God was always in my mother. It was reflected in the love demonstrated every day by my father and in the inspiration their relationship gave others, as well as in the opportunity my mother gave the staff to care for another in great need.

John Page, Cary, NC

Sacred Reverb

Molly Worthen writes that “today’s contemporary worship music” is “trying to use music to do as Paul did [in becoming ‘all things to all people’]: to entice seekers, disciple those already in the church, and worship God.” This implies that there should be no difference between the styles of music at an evangelistic service and at a worship service. This is open to question, primarily since the Book of Acts does not record any instances of music being used as a tool for evangelism and secondly because countless generations of Christians have been strengthened in their spiritual walks by distinctively “sacred” music. Examples include plainchant, Bach chorales, and Black spirituals.

Worthen quotes Bryan O’Keefe as saying that when he hears contemporary Christian songs, he starts to “mentally connect them to [his] own experience.” Obviously, the key issue here is relevance. But what about the flip side of the coin? That is, what about the experience of transcendence a listener has when he hears plainchant? Or the lofty, otherworldly spirituality of Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina? Such music is not intended to be “relevant.” Rather, it’s up to the listener to relate to the music. Surely this is appropriate for the worship of a transcendent God whose ways are higher than our ways.

John Harutunian, Newton, MA

As a young person in the 1970s and ’80s, there are many choruses I recall from Sunday school, youth camp, and even our weekly Cru meeting on campus. This was an era of the sole guitar leading music. Many of these were direct quotes of a line or two of Scripture, put to music and often repeated multiple times. Even today, 40–50 years later, I still hear those songs in my head when I am reading devotionally, so much so that when writing in my Bible I put little musical notes next to verses I recall the songs to.

Bob Mac Leod, Orlando, FL

An Exhortation to the Exhausted Black Christian

“This is going to sound revolutionary for some Christians. And that is a problem.

Sean Tripline, Facebook