My husband and I moved into a low-ceilinged basement apartment on a snowy day in January. The landlord was related to a prominent Nigerian poet, which boded well for our literary future, I thought. Combining our books into a single collection was one of the first tasks of our young marriage.

I was unpacking a box of my husband’s when I pulled out a book I’d never seen before. I stood upright to get a good look: Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain by Betty Edwards.

“What’s this book?” I called to my husband, holding it up.

“From an art class I took,” he said.

I turned it over and read the summary. On the back were before-and-after student drawings. The “afters” were sophisticated self-portraits. I felt a stab of envy.

In preschool, some of my work had gotten my parents excited about my creative potential. They commissioned little ink drawings from me that they cut to size and printed in our family letter at Christmas time. They signed me up for private art classes. I went weekly to a neighborhood studio, where I worked on textured paper with waxy pastels that lay side by side in a neat, boxed array.

I failed to develop as an artist.

There was some household discussion about this. Most of the blame landed on the art teacher—she was apparently not a serious instructor. I was more inclined to chalk it up to my own defects. Privately, I found the whole thing alarming. In class, I didn’t know what was going on. Drawing was not like reading or math, which I had picked up seemingly without effort.

The best I could manage was mimicry. I memorized step-by-step procedures that made it seem like I could draw. My proudest achievement was a little dog-grass-rainbow cartoon that pleased my 8-year-old, anxious-to-succeed heart to no end and that I reproduced for friends and relatives for years. It was flat and trite, but at least it looked like I knew what I was doing.

I never quite learned to draw. That’s not to say I couldn’t draw some when I wanted to. In school, I drew scenes from Oliver Twist and Watership Down, and I was pleased with them.

But I admired work by people who actually could draw, like my friend Dan. His senior-year art show featured a bold painting of a man whose shouting mouth opened like a tunnel for a twisting road, running out against a fiery turbulent sky. He was even commissioned to paint a tiger on the floor of the basketball court. It was beautiful.

Maybe what I admired most was how the true “art kids” spent time drawing as though it were just as important as classes like chemistry and calculus. Art was fine as a hobby, I thought, like tennis—except I only played after school and on my own time. Drawing wasn’t really something serious to study. It wasn’t going to get me into college or a prestigious career.

“When did you take an art class?” I asked my husband, emerging from my reverie.

“In high school,” he said.

I frowned at this. I had never taken an art class in high school, or any time other than with the neighborhood instructor. I’d never permitted myself to try to learn to draw. I wasn’t sure I could handle it if I turned out to be bad at it.

My husband is very talented, but I had seen enough of his skill set to doubt that he was any more likely than me to excel at drawing. Indignant, I wondered: How come he got to learn to draw in high school, and I didn’t?

“Why did you take an art class?” I asked.

“I wanted to,” he said.

I thumbed through the book’s pages and glimpsed a full-page illustration. I stopped to look: Igor Stravinsky by Pablo Picasso, depicted upside down.

Drawing “Igor Stravinsky” upside down, the author explained, was an exercise to help students train their artistic perception. Most of us see with habitual “left brain” patterns that are symbolic, verbalized constructs: Here is an orange; that is a hat. When we learn to draw, these preconceptions often get in the way.

We need a perceptual shift into a more “right-brain” mode that is more interested in shape and tone, lengths of line, arcs of curves, and spatial fit. Learning to draw, Edwards claimed, is mainly about learning to see.

I thought that was interesting. But I had boxes to unpack, studying to do, and a marriage to figure out. I closed the book and put it into the empty place on the shelf.

Twelve years later, I was a mother to three young children who had come to our home on a late summer day from their previous foster family and were now ours for good. Daily life seemed precarious. Simply getting through the day was too much to do most of the time. My husband and I threw ourselves into caring for them. We had a frantic sense that through our individual effort we might be able to undo the damage done in their early childhood and halt the effects of reactive attachment disorder or fetal alcohol syndrome.

By the time the kids were in bed each night, I was depleted and keyed up. Most people in this state probably turn to television, but the idea of lounging there, unproductive, was hateful to me. I felt stunted and wanted to do something “improving.” I wanted to handle physical materials. I pick at my nails in times of stress, and they were a mess now. I needed to keep my hands busy.

So, one day in late fall, I pulled Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain down from the shelf and started reading.

Almost everyone can learn to draw, Edwards says, just like almost everyone can learn to read. If we can just shift out of the symbolic view—what we think we see—to see what is truly there, then we can draw. All it takes is some training in the five perceptual skills, seeing “edges, spaces, relationships, lights and shadows, and the gestalt”—the coherent whole.

I wanted to see that way.

I got out paper, pencil, and eraser and set to work on Igor Stravinsky upside down. After three quarters of an hour, I made my last stroke and turned the paper right side up. It resembled Picasso’s original. I smiled with satisfaction. Not bad.

Emboldened, I darkened the negative spaces around a wooden chair. I sketched my hand, marking the crevices in my knuckles and the moons of my nailbeds and the curves of my finger pads. I timidly shaded a saltshaker and avocado with hatch marks, then crosshatched them with more confidence.

Drawing people was intimidating. The book warned me about not giving people a “chopped-off skull” by underestimating how big the back of the head is. Even Vincent van Gogh, who learned to draw at age 27, had “problems of proportion” early on, giving people outsized hands and chopped-off skulls. But by age 29, he was a skilled portraitist.

My first portraits were from photographs. I drew my daughters in various poses and then my sister in a three-quarters profile view. I didn’t cut off her skull, but I messed up the placement, and her features were a bit crammed onto the paper. I put it in a frame above my sink, pleased to see her familiar smile in my own pencil marks. When she visited, I showed her.

“Look, I drew you,” I said expectantly.

She glanced at it. “That does not look like me,” she said.

“What do you mean?” I was taken aback. “That looks exactly like you.”

She pursed her lips. We didn’t discuss it further.

When she left, I kept it right where it was. It looked exactly like her, and I liked having her near, even if she didn’t appreciate it.

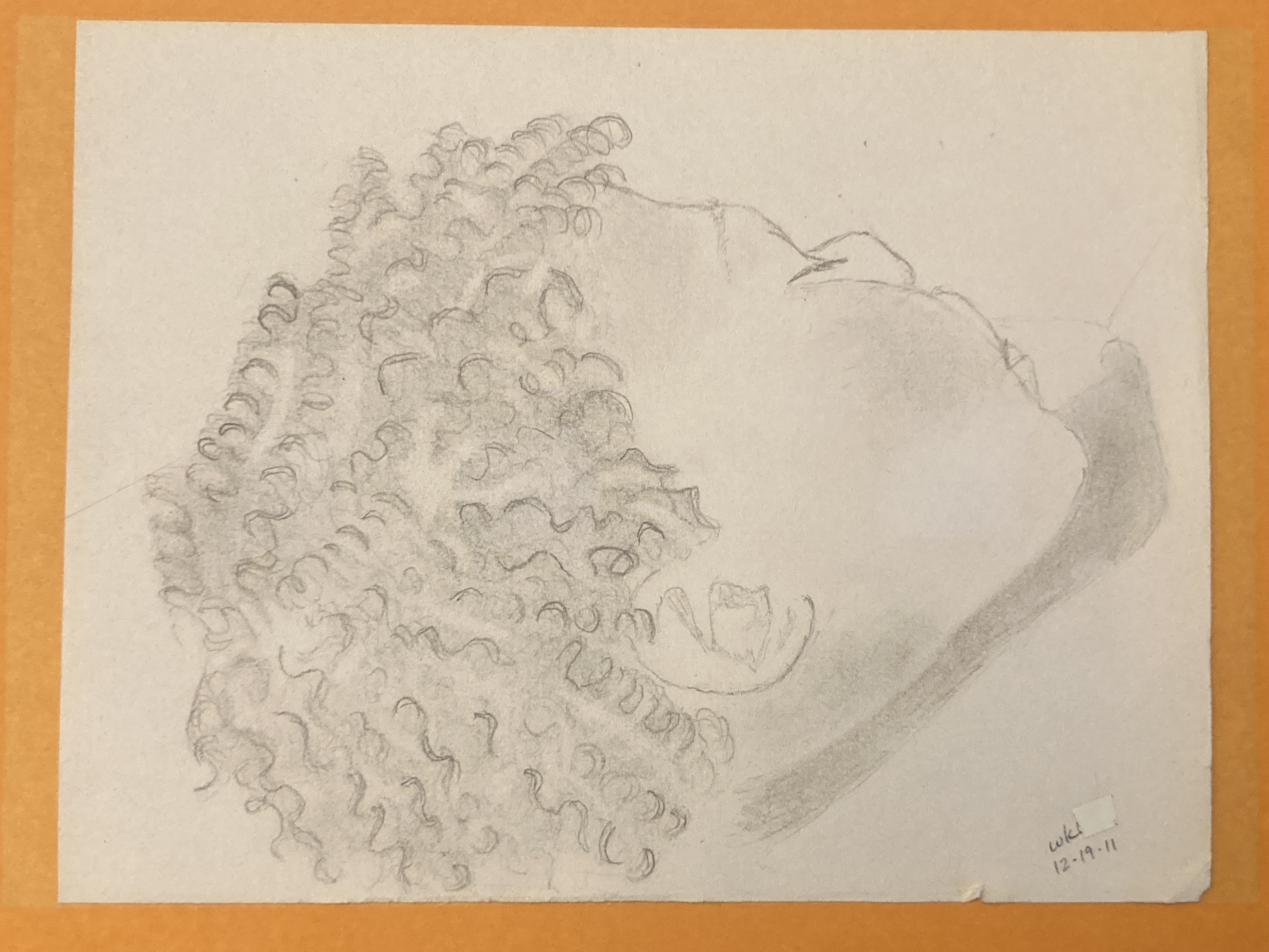

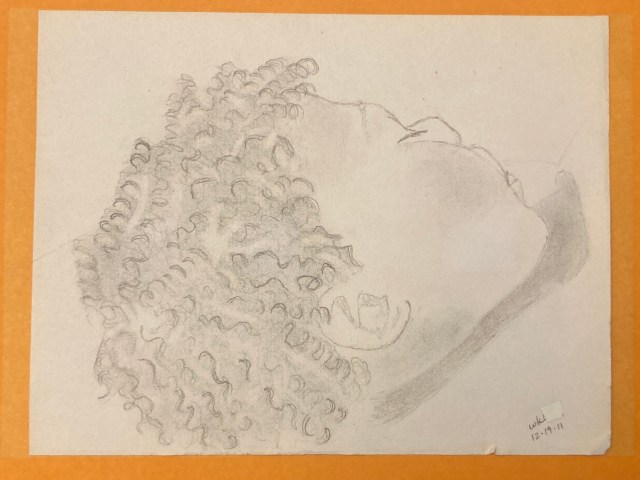

My husband was a sitting duck as a live model, and I tried to draw him—once while he was leaning back on the sofa with his legs crossed as he talked on the phone with his brother, another time as he typed on his laptop.

These drawings were okay. They didn’t have skull problems, but the mouths didn’t look right. Mouths are hard. If you study them carefully, they are more line-and-shadow than lip, and very unforgiving. The merest dip or lift makes your loved one into a monster or a clown.

In the winter, we traveled to visit family. The children had never flown before. They were anxious and out of sorts to begin with, and the new surroundings only dysregulated them further. They also got sick and spent the week vomiting and running fevers.

On the return trip, I was sad and exhausted from the stress of caregiving. There was bad weather in the northeast, and we got into our seats late in the evening. My daughter badly needed sleep but was nervous and squirmy. I laid her head in my lap and covered her with a jacket. She fell asleep. I sat still for a while, then gingerly reached down for my drawing pad and set about sketching her sleeping face. I traced her round cheek, the delicate arch of her eyebrow, the tiny flare of her eyelashes, the folds of her ear. I was struck with tenderness.

“Absolute unmixed attention is prayer,” writes Simone Weil. I see what she means. That drawing from the airplane, when I see it now, brings me to that exact posture and state of feeling. I see the vulnerable beauty of her little face before me, but I feel also the heft of her body, the care I took not to jostle her, the drone of the jet engines, the gratitude for the gift of her sleep, and the temporary reprieve from worry. I saw her, I believe, somewhat as the Lord himself sees her: beloved and under his care on this difficult, uncertain path of life. And what I have seen will not be taken away.

Choosing what to draw is one of my major hang-ups. I want to draw the important and beautiful things—the smooth-skinned faces of my children, my mother’s hands, my dog’s velvety snout, the sweep of cirrus clouds across the sky. But they are complicated. I have neither the skill nor the time to capture them.

Most instructors say that subjects are all around, and the most ordinary things are great for drawing. Office supplies on your desk. Dishes piled in the sink. The bare trees crossing limbs overhead.

These still-life options are easier because they don’t move. The more compelling scenes are fleeting. Friends alter their postures, cityscapes blur, animals shift, water moves, weather changes.

At church or gathered with friends, in waiting rooms or meetings, in restaurants and on sidewalks, I sometimes sit back and try the perceptual shift. What could I draw? The water glass on the table? The young man bent over his phone? The worshipers standing in song? I case the joint, watching.

Author Wendell Berry’s fictional barber Jayber Crow spends his many slow hours watching his little town. “I was always on the lookout for what could be revealed,” he says. “Sometimes nothing would be, but sometimes I beheld astonishing sights.”

Jesus’ initial call to his disciples is simply Come and see (John 1:39). Jesus requires very few specific tasks of his disciples, but he is insistent that they watch and “see” what he is about.

After Jesus has risen, his disciples realize their salvation is at hand and declare it simply: “We have seen the Lord!” (John 20:25).

I have not yet reached a level that good artists achieve, of being able to draw from memory. I can put down only what is right in front of me—and only if it doesn’t move too fast.

The pastor at our church preached recently on Luke 7. Jesus is reclining at table with Pharisees when a woman walks in to anoint his feet. Everyone is aghast, but Jesus beholds her joyfully. He turns to his host and asks, “Do you see this woman?” (v. 44).

“Well, of course the pharisees saw her,” my pastor said. She was all too visible. They looked and saw scandal. They missed the color and tone, the gestalt of what Christ saw, the hidden power of God’s inbreaking kingdom.

How often do we too fail to mark the signs of his kingdom?

What do I see, pen and paper before me? Do I see and worry about my children’s struggles and careless mistakes? Yes, but I cannot draw them. My son reading a book, the way he looks self-consciously down while talking—these I might draw. I see my daughter tidying the kitchen and the way her smile spreads across her face. I treasure them and ponder them in my heart. Seeing is the way of love.

In each image I attempt to draw, I am forced to acknowledge how much I must leave unseen. My powers of sight cannot encompass all that is there. I cannot see all the wisps of cloud striating the sky. I cannot draw each filament of curl on my son’s head. I cannot catch the exact lines of amusement in my friend’s smile.

To produce a good drawing, an artist must know when to stop. Art can be ruined by trying to put in too much. I must leave undrawn thousands of snowflakes clumped on the branches of a red cedar, myriad glinting droplets shivering on the twigs of a young maple. These are exquisite beauties that yet must remain undrawn and mostly unseen by all but their Creator.

Drawing is a way of entrusting what I can see to the care and attention of God, who is El Roi, the “God who sees” (Gen. 16:13). The Lord’s seeing is not merely passing notice but rather a powerful activity of loving concern.

When God intervenes in Abraham’s sacrifice of his son Isaac, Abraham looks up and sees a ram nearby, caught by its horns, and offers it in sacrifice instead. He names the place, “The Lord Will Provide.” The verb rendered provide is the Hebrew word for see (Gen. 22:14).

I pray only as I partly see, and the Holy Spirit must see all and intercede for all that needs the Lord’s attention. The cares furrowing my husband’s brow are only partially seen by me, his closest companion. My children’s futures, too, the Lord must provide for. He is the shepherd of their hearts, their lives’ pains and pleasures, and all they must experience and learn.

My drawings are not always as I would wish, yet I am drawn to marvel at the provision of the One Who Sees. He alone will redeem all my errors in perception; and he is healing all things, hidden and visible, whether I can draw them or not.

Wendy Kiyomi is an essayist whose writing on the trials of faith, complexities of adoption, and delights of friendship has appeared in Plough Quarterly, Image Journal, Christianity Today, Mockingbird, the Englewood Review of Books, and at wendykiyomi.com. She lives in Tacoma with her family and is a 2023 winner of the Zenger Prize for journalistic excellence.