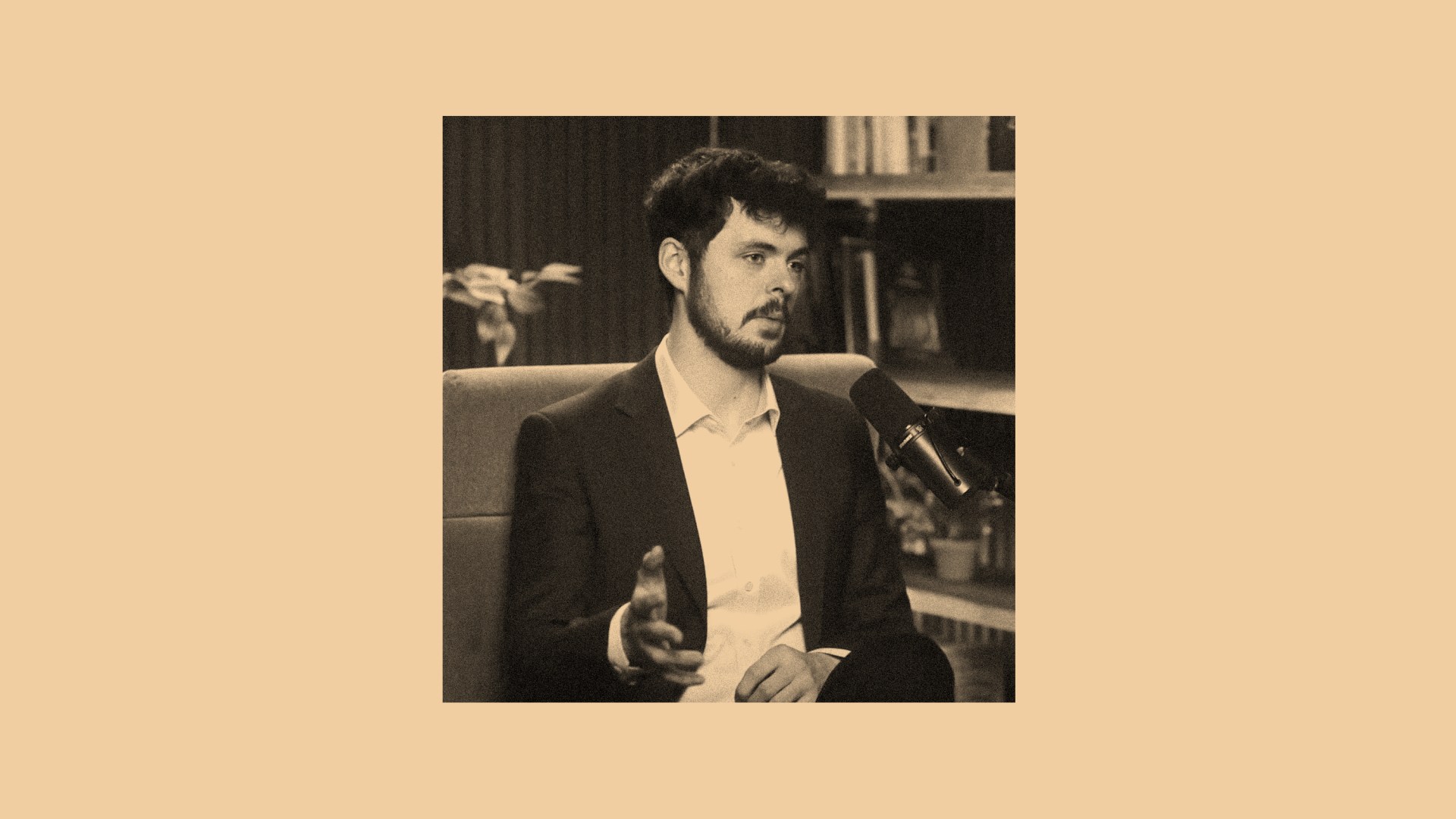

Pamphlets with a photo of Brent Leatherwood alongside House Speaker Mike Johnson dotted thousands of gray chairs in the Dallas meeting hall where the Southern Baptist Convention (SBC) gathered in June.

Leatherwood, the president of the embattled Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission (ERLC), spoke from the US Capitol lawn in a promotional video touting Southern Baptists’ lobbying efforts in Washington. He pleaded with the convention to allow its public-policy arm to continue its work.

Ultimately, it was enough for the ERLC to withstand calls for its elimination and for Leatherwood to keep his job.

For seven more weeks.

Leatherwood stepped down Thursday, the culmination of a tumultuous few years when growing numbers of Southern Baptists saw him and the ERLC as out of line with their own political stances and everyday church life.

ERLC board members accepted his resignation and thanked him for his leadership during a divisive time, appointing chief of staff Miles Mullin as acting president in the interim. Leatherwood—a 44-year-old church deacon who previously worked for the Republican Party in Tennessee and on Capitol Hill in DC—did not cite a reason for his departure, only that it was “time to close this chapter of my life.”

“His resignation from the ERLC is a sign of how difficult it is to represent Southern Baptists in the political sphere … and to do it in a time of polarization in the convention,” said Griffin Gulledge, pastor of Fayetteville First Baptist Church in Georgia and a leader with The Baptist Review.

At the SBC’s annual meeting this year, 43 percent voted to abolish the ERLC. The proposal didn’t pass, but the split showed dwindling confidence in the entity. Even Albert Mohler, president of The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, had spoken up in an interview to voice his “grave doubts about the utility of the ERLC.”

The ERLC’s most vocal detractors consider the entity’s activity as evidence of broader liberal drift in the conservative denomination, calling out positions on immigration and guns. Other pastors saw Leatherwood’s ERLC as detached from the 47,000 local congregations that make up the SBC.

In the weeks since the annual meeting, Leatherwood stayed hard at work as the ERLC saw major news unfold: a string of Supreme Court rulings at the end of June and the congressional budget reconciliation bill in July. Both included moves toward a longtime ERLC aim of defunding Planned Parenthood.

Amid all the public responses to political happenings, Leatherwood prepared another statement for the ERLC board: his resignation.

The trustees had discussed Leatherwood’s future at ERLC before. Last year in July, he faced online backlash for calling Joe Biden’s decision to drop out “a selfless act.” The next day, the ERLC’s former board chair erroneously declared that Leatherwood had been fired—only for the ERLC to retract the announcement since the decision came without a formal vote.

In the SBC, the convention votes in trustees for each entity, and the trustees oversee entity leadership.

Even among ERLC supporters, many left the meeting in Dallas last month assuming that if the ERLC gets to stay, it’ll have to make changes—likely starting at the top.

“The messengers to the SBC annual meeting have signaled with their ballots over the last couple of years that trust has been breached and must be rebuilt,” said Andrew Hébert, a pastor from Longview, Texas.

Former ERLC presidents drew from their theological and pastoral backgrounds to speak into current issues; Leatherwood brought public policy know-how that positioned him well in DC but, to some, made him feel less connected with the people in the pews.

“I am praying that the trustees will choose someone who understands the churches of the Southern Baptist Convention and can wisely represent their concerns in the public square,” said Hébert. “Policy experts can be hired, but the leader of the entity must know how to engage with pastors and churches.”

Much of the criticism directed at the ERLC predates Leatherwood, back to Russell Moore’s “never Trump” stance during his tenure leading the entity nearly a decade ago. (Moore now serves as editor in chief of CT.) And Moore’s predecessor, Richard Land, said disagreements over the ERLC’s work are “inevitable” but its work remains crucial.

Senator James Lankford, an Oklahoma Republican and a fellow Southern Baptist, recently thanked Leatherwood for his engagement in Washington.

“He has a very challenging task to be able to speak for us without speaking for us,” Lankford said at an ERLC event during the SBC annual meeting, underscoring the independence of Southern Baptist churches. “He’s everywhere. He’s speaking out about abortion, about adoption, about international religious liberty. … He’s out there working on it.”

Leatherwood, in his earlier appeals, defended the significance of having a Baptist voice in Washington and downplayed his own stances. “This is not about me,” he said in a video. “This is not my entity but yours,” he told the convention crowd.

Leatherwood’s children survived the 2023 Covenant School shooting in Nashville, and some Southern Baptists objected to his advocacy for a state law to restrict guns from people deemed a threat to themselves or others. The ERLC also faced ongoing criticism and defended itself against accusations of being pro-amnesty for its advocacy around refugees and involvement in the Evangelical Immigration Table.

The SBC operates as a convention bringing together independent churches rather than a hierarchy, so individual Southern Baptists often disagree on approaches to political and cultural issues and how the convention should engage.

In recent years, leaders beyond the ERLC have grown their platforms and resources to engage Southern Baptists around political and cultural commentary. Mohler at Southern Seminary discusses current events on his popular Briefing podcast each weekday. The Center for Baptist Leadership, a group within the SBC that wants to see conservative revitalization, offers articles and podcasts, saying it aims to “serve as a better Baptist voice in the public square.”

After Leatherwood’s resignation, Mohler said, “Southern Baptists will be grateful to Brent Leatherwood for the investment of his life and work through the Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission,” and extended prayer for him, his family, and “the future and faithfulness of the commission itself.”

Scott Foshie, the chair of the ERLC board of trustees, called Leatherwood “a consistent and faithful missionary to the public square.” A fellow trustee, Mitch Kimbrell, cited the pro-life advances made under Leatherwood, including defunding Planned Parenthood and donating 40 ultrasound machines to pregnancy centers.

Leatherwood’s statement said, “It has been an honor to guide this Baptist organization in a way that has honored the Lord, served the churches of our Convention, and made this fallen world a little better.”

Mullin, the ERLC’s current vice president and chief of staff, will take over for Leatherwood in the meantime. Before the ERLC, Mullin worked in Christian higher education and taught church history; he holds a master’s degree from Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary and a PhD from Vanderbilt University.

The board has not yet announced a search committee to find Leatherwood’s replacement—a tough ask given the $3.3 million entity’s contentious place in the SBC today. “Even as your smallest institution, we attract outsized attention and scrutiny,” Leatherwood told the convention in June.

“A lot of people are wondering if there’s anyone who can navigate the pressures of this job or withstanding the daily brunt of well-funded antagonists,” said Gulledge. “Whoever the trustees choose to lead the organization in the future must be committed to doing the hard work to rebuild the relationship between the ERLC and the churches and pastors it represents.”

This is a breaking news story and has been updated.