A proposed online database that would list the names of abusive Southern Baptist pastors is now on hold, with no names likely to be added to the website by the denomination’s annual meeting this summer.

Instead, Southern Baptist leaders working to address abuse in the nation’s largest Protestant denomination say they will focus on helping churches access other databases of abusers and training churches to do better background checks. However, the so-called Ministry Check database, which was a centerpiece of reforms approved by Southern Baptist messengers—or local church representatives—is now on the back burner.

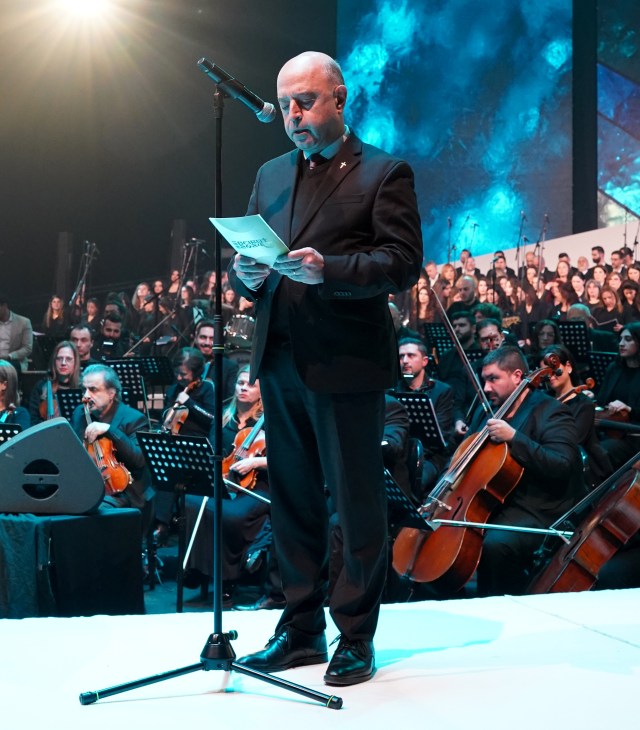

“At this point, it’s not a focus for us,” Jeff Iorg, head of the Southern Baptist Convention’s Executive Committee, told reporters at a news conference Tuesday during the committee’s annual meeting in Nashville.

The proposed database has been derailed by denominational apathy, legal worries and a desire to protect donations to the Southern Baptist Convention’s mission programs, RNS previously reported.

Sexual abuse survivors have been advocating for a database of abusers since at least 2007, when ABC News’ 20/20 published a report on abuse among Southern Baptist pastors. The Executive Committee rejected the idea in 2008, but it resurfaced in 2021 after a Guidepost Solutions investigation found Southern Baptists had long downplayed the issue of abuse in the denomination and mistreated abuse survivors who tried to raise the alarm about the issue.

That led to initiating reforms, which were to include building education for churches and creating the Ministry Check database. For years, an SBC task force charged with implementing reforms said the database would soon go live, once concerns about finances and legal issues were overcome.

A website for SBC abuse reform, which SBC leaders called “historic” when it was launched in 2023, included a link to the Ministry Check website. However, no names appear on that site.

“Coming soon, Ministry Check will provide leaders with the ability to search for information about individuals who have been convicted, found liable or confessed to abuse,” the website reads.

The delay in adding names to the database, among other delays, led some advocates to wash their hands of the SBC’s abuse reform efforts.

“Accountability is illusion and institutional reform is a hall of mirrors,” wrote Christa Brown, a longtime advocate of SBC reforms, and other abuse survivors in a recent editorial.

Iorg did not rule out future work on the database but said it would not happen soon. Jeff Dalrymple, who was recently named to head up the SBC’s response to sexual abuse, also said he would not rule out future work on a database.

A now-disbanded task force charged with implementing the SBC reforms, including the database, started a nonprofit last year called the Abuse Reform Commission. However, its proposal for funding was rejected by the heads of the mission boards.

Earlier in the meeting, Iorg outlined a set of priorities for responding to and preventing abuse, including providing more training for churches and working more closely with the denomination’s state conventions of churches. He also gave thanks for Dalrymple’s new role, which he said would help move the reforms and response to abuse forward.

Iorg said more data was needed about the scope of abuse in the denomination and steps churches are taking to prevent it and respond when it happens.

A 2024 report from Lifeway Research, which is owned by the SBC’s publishing house, found that only 58 percent of churches did background checks on those who work with children; those checks are considered one of the essential steps in abuse prevention.

Dalrymple, who was previously executive director of the Evangelical Council for Abuse Prevention, a nonprofit that addresses abuse, said helping churches deal with abuse was part of his calling in life.

The news the database has stalled was both disappointing and expected for abuse survivors Jules Woodson and Tiffany Thigpen, who have long advocated for reforms. Both said that because the SBC does not oversee its pastors and because abusers only make it onto criminal databases after convicted, a list of abusive pastors is necessary.

After years of delay, Thigpen said at least survivors have an answer about the future of the database.

“I’m just glad it was said out loud,” she said. “So now we are off the hook for hope.”

Thigpen said Tuesday’s meeting felt like the end of an era for survivors who have pushed for reform and that SBC leaders have moved on. But she said that even though the database seemed doomed, Southern Baptists can no longer say abuse is not a problem.

Woodson said the move away from a database showed the will of church messengers doesn’t matter in the end. Southern Baptist leaders, she said, will do what they think is best, no matter what anyone else says. She compared the SBC abuse issues to a house on fire—and instead of calling the fire department, Southern Baptists asked a board of directors to put the fire out. That left them standing around with buckets while things burn.

“They should have called the fire department,” she said.

The cost of dealing with abuse was also on the minds of Iorg and other Baptist leaders meeting in Nashville. Legal costs from the Guidepost investigation and the abuse crisis generally have totaled $13 million and drained the Executive Committee’s reserves. On Tuesday, Executive Committee members recommended a 2025 budget for the denomination’s Cooperative Program that includes a $3 million “priority allocation” for legal costs.

That allocation will have to be approved by SBC messengers this summer at the denomination’s meetings in Dallas and will likely be controversial. Cooperative Program funds from churches are used to pay for missionaries, seminary education, church planting and other national ministries—and previous attempts to tap SBC’s Cooperative Program funds to address the issue of abuse stalled.

So far, SBC abuse reforms have been funded by an initial $4 million from Send Relief, a joint venture of the SBC’s International Mission Board and North American Mission Board. No permanent funding plan is in place.

Iorg said the “priority allocation” has been the subject of vigorous debate and called it “the most palatable of a lot of bad options.”

He also said the messengers to past SBC meetings authorized the investigation into abuse, and the legal cost is part of the consequences of that decision. He noted the Executive Committee is actively trying to sell its building, which could help with legal costs.

When asked if he regretted past decisions that led to the costs, Iorg said addressing abuse was the right thing to do, though he wished Southern Baptists had found a way to do it that was not as costly or disruptive.

During the meeting, Southern Baptist leaders also removed two churches from the denomination—one in California over the issue of abuse, and a second in Alaska due to having “egalitarian” views about the roles of men and women in leadership. The SBC’s statement of faith has restricted the role of pastor to men, and in recent years the denomination has become more aggressive in removing churches with women pastors.