NEWS

NATIONAL ELECTIONS

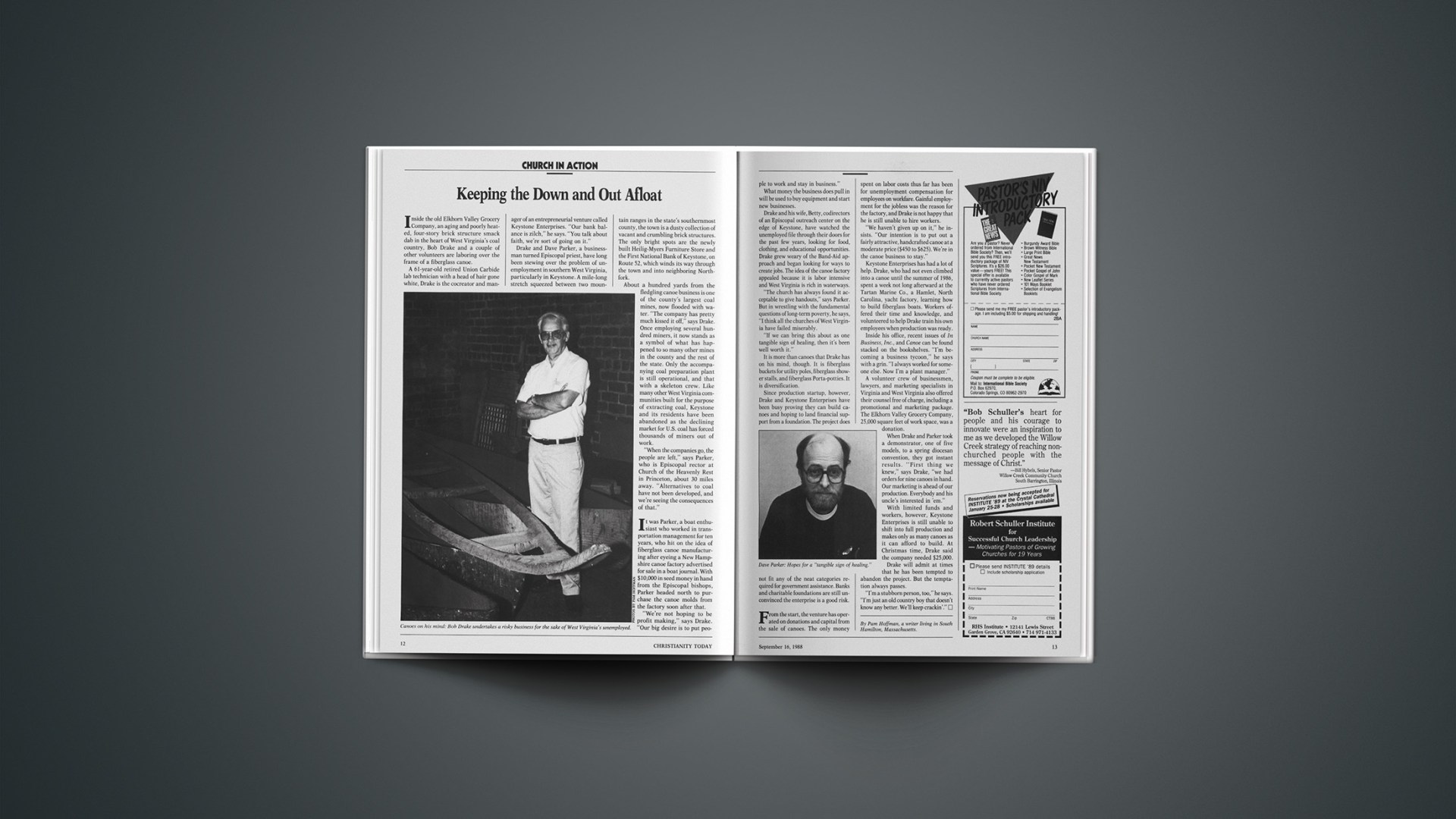

A conservative platform may help George Bush hold on to Democrats who helped elect his boss.

With the conventions behind them, Michael Dukakis and George Bush have cranked up their campaigns another notch as they head for their November showdown. The Democrats will try to recruit the so-called Reagan Democrats who voted for Ronald Reagan in 1980 and 1984 (CT, Sept. 2, 1988, pp. 38–10). Conversely, Republicans hope to hold on to the coalition that gave them the White House for the past eight years.

Polls show that an important part of that coalition was the evangelical community, which in recent years has turned from its traditionally Democratic leanings to vote Republican in the presidential elections. By November, it should be clear whether it was the person of Ronald Reagan or the priniciples of the Grand Old Party (GOP) that has attracted such a large percentage of the evangelical community.

Family, Faith, And Freedom

The Republicans claim it was their principles that attracted conservative Democrats; and indeed, the 1988 party platform has won high marks from conservative Christian groups. GOP leaders speak proudly of their 105-page document, which is nearly ten times the size of the Democratic platform. Claiming the Republicans were not ashamed of what they believe in, Platform Committee Chair Kay Orr of Nebraska said “family values, patriotism, and the belief in God” are an “integral part of the platform.”

Among the principles articulated in the document:

• Opposition to abortion and abortion funding; opposition to the withholding of care and medical treatment on the basis of age, infirmity, or handicap; support for the appointment of judges that “respect traditional family values and the sanctity of innocent human life.”

• Defense of religious freedom, including support for voluntary school prayer, equal access to school facilities for student religious groups, and the daily recitation of the Pledge of Allegiance in public schools; condemnation of the American Civil Liberties Union’s attacks on the tax status of the Catholic church and other religious institutions.

• Support for the emphasis that “abstinence from drug abuse and sexual activity outside of marriage is the safest way” to avoid contracting AIDS.

• Pledges to fight drug abuse, pornography, homelessness, and crime.

• Support for the family in all government policies, particularly in economic areas such as tax benefits and opportunity for self-help.

The 1988 platform echoes previous Republican platforms in advocating the Strategic Defense Initiative and a “peace through strength” philosophy, but it breaks with the past in devoting more attention than ever before to environmental and poverty issues.

God’S Own Party?

Many observers say the conservative nature of the platform is due partly to the Christian influence within the party—an influence that was especially unmistakable during the convention. Estimates that as many as a third of the delegates were born-again Christians gave a deeper meaning to Reagan’s joke that he always knew when he got to the “home of the Saints, they’d all be Republicans.”

From the delegates to the speakers, evangelicals played a prominent role in the convention. On one night alone, evangelicals Sandi Patti, E. V. Hill, Kay James, William Armstrong, Elizabeth Dole, Jack Kemp, and Billy Graham were all on the program.

The lingering influence of Pat Robertson and his supporters was also present at the convention, but is likely to be a bigger factor in the days to come. Robertson has given his full support to Bush and is promising to campaign actively for the Republican ticket. In the interests of party unity, a tentative peace has been declared in many of the bitter struggles waged at the state level over recent months between Bush and Robertson factions of the GOP.

At a joint press conference, Robertson and the Vice President’s son George W. Bush declared a truce in the “Civil War II” that had been going on for two years over the delegate selection process in Michigan. “We had a tough fight in Michigan,” Robertson said, “but we’re no longer in a position to fight Republicans. We have to fight Democrats.”

Yet, tensions remain in many states between party regulars and the new Robertson activists. Robertson supporters have taken control of “party machinery” in Hawaii, Alaska, Washington, and Nevada and have a significant influence in several other states. Robertson delegate David Paco, a former Democrat from Hawaii, acknowledges there are still tensions in his state, but he is hopeful things can be resolved. “I think there is an attempt to build together,” he said. “It’s just a matter of time, because the wounds are still so fresh.”

Contrary to much early speculation, both Robertson and his supporters appear to be in Republican politics for the long haul. Many Robertson activists are throwing their hats into local political races.

But Robertson supporters do not represent the only evangelical presence in the GOP. Many Christians began active involvement in party politics in 1980, with the help of Reagan and a number of grassroots groups like the Moral Majority. Many of those more experienced Christian activists supported candidates other than Robertson.

Arkansas State Rep. Tim Hutchinson, general manager of a Christian radio station, is one such Bush delegate. Hutchinson said he believed Bush was the “strongest standard bearer for the fall.” According to Hutchinson, the Robertson campaign will have a significant impact on the entire party structure in his overwhelmingly Democratic state by bringing many new people into the process.

Hutchinson called the intraparty tensions “inevitable” because of the altering of the state-level GOP power structure. Also, he noted that some of the new Christians “are very much political novices and sometimes go about things in less-than-diplomatic ways.” Yet, he said, “the establishment wing of the party needs evangelicals and vice versa, so the coalition has to stay together.”

Reaching Out

Republicans are hoping their efforts will keep conservative Christians—including the evangelical Reagan Democrats—in the coalition. The Bush campaign has formed a Family Issues Coalition to reach out to people who advocate traditional family values. Doug Wead, director of the coalition, has been acting as the campaign’s liaison to the evangelical community and says evangelicals will be involved in all aspects of the campaign.

Bush may further endear himself to evangelicals with his recent statements about his faith in God (see interview, p. 40). And the choice of Sen. Dan Quayle—a Presbyterian—as a running mate also pleased conservative Christians.

Christian leaders in the party assert the GOP has much to offer evangelicals. Ohio Congressman Bob McEwen believes the Republicans can retain the votes of the Reagan Democrats even though Reagan is not on the ballot. “It’s not the person, but the values of the platform and the principles that will be implemented that are at risk,” he said. Colorado Sen. William Armstrong agrees. “The contrast between where Mr. Bush stands and Mr. Dukakis stands on issues that are absolutely fundamental—particularly on things evangelicals stand for—is very, very direct,” he said.

By Kim A. Lawton in New Orleans.

Friendly Confines

Media coverage of last month’s Republican convention left some stories untold:

Cabinet preacher. Interior Secretary Donald Hodel invited delegates attending an ecumenical prayer breakfast to give their lives to Christ. He and his wife, Barbara, began by relating how the suicide of their 17-year-old son led them to trade their “cultural Christianity” for a personal relationship with Jesus Christ. “If you have never asked Christ into your life, I’d like to close with an opportunity for you to pray that prayer,” Hodel said.

Mutual fans. Vice President George Bush and contemporary Christian singer Sandi Patti are apparently big fans of one another. Bush requested that Patti sing the National Anthem at the convention after he heard her performance during the Statue of Liberty Celebration in New York. According to a campaign spokesman, Bush “loves her music” and often “pops her cassettes into the player.” For her part, Patti says she is a “big Bush supporter.”

Nonpartisan praying. Evangelist Billy Graham, who reminded reporters he is a registered Democrat, stayed in New Orleans for the entire convention. President Reagan had asked Graham to give the invocation the night he addressed the convention, and the Bushes asked their long-time friend to be with the family the night the Vice President accepted the nomination. Careful to remain nonpartisan, Graham was also at the Democratic convention in July, and he prayed a similar prayer at both events.

Family ties. In keeping with convention themes of faith and family, the Bush campaign sponsored a week-long “Salute to the Family” and gave special awards to individuals promoting “traditional family values.” Among the honorees: Teen Challenge’s Snow Peabody, Angie Holroyd of Clean Teens USA, Jean Johnson, wife of Assemblies of God General Chairman Don Johnson, Ruby Lee Piester of the National Committee for Adoption, and the Robert Schuller and Jerry Falwell families.