NEWS

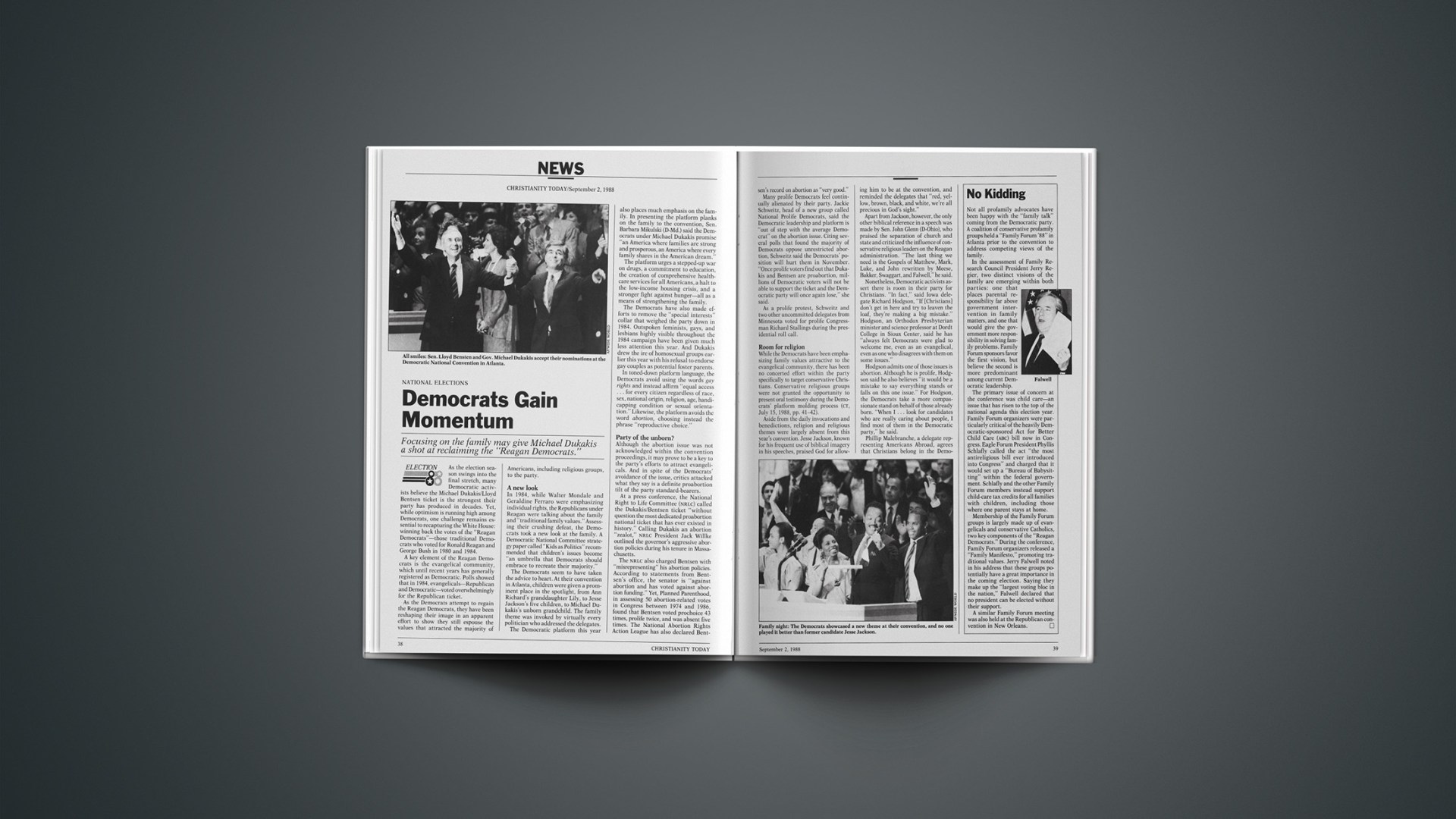

NATIONAL ELECTIONS

Focusing on the family may give Michael Dukakis a shot at reclaiming the “Reagan Democrats.”

As the election season swings into the final stretch, many Democratic activists believe the Michael Dukakis/Lloyd Bentsen ticket is the strongest their party has produced in decades. Yet, while optimism is running high among Democrats, one challenge remains essential to recapturing the White House: winning back the votes of the “Reagan Democrats”—those traditional Democrats who voted for Ronald Reagan and George Bush in 1980 and 1984.

A key element of the Reagan Democrats is the evangelical community, which until recent years has generally registered as Democratic. Polls showed that in 1984, evangelicals—Republican and Democratic—voted overwhelmingly for the Republican ticket.

As the Democrats attempt to regain the Reagan Democrats, they have been reshaping their image in an apparent effort to show they still espouse the values that attracted the majority of Americans, including religious groups, to the party.

A New Look

In 1984, while Walter Mondale and Geraldine Ferraro were emphasizing individual rights, the Republicans under Reagan were talking about the family and “traditional family values.” Assessing their crushing defeat, the Democrats took a new look at the family. A Democratic National Committee strategy paper called “Kids as Politics” recommended that children’s issues become “an umbrella that Democrats should embrace to recreate their majority.”

The Democrats seem to have taken the advice to heart. At their convention in Atlanta, children were given a prominent place in the spotlight, from Ann Richard’s granddaughter Lily, to Jesse Jackson’s five children, to Michael Dukakis’s unborn grandchild. The family theme was invoked by virtually every politician who addressed the delegates.

The Democratic platform this year also places much emphasis on the family. In presenting the platform planks on the family to the convention, Sen. Barbara Mikulski (D-Md.) said the Democrats under Michael Dukakis promise “an America where families are strong and prosperous, an America where every family shares in the American dream.”

The platform urges a stepped-up war on drugs, a commitment to education, the creation of comprehensive health-care services for all Americans, a halt to the low-income housing crisis, and a stronger fight against hunger—all as a means of strengthening the family.

The Democrats have also made efforts to remove the “special interests” collar that weighed the party down in 1984. Outspoken feminists, gays, and lesbians highly visible throughout the 1984 campaign have been given much less attention this year. And Dukakis drew the ire of homosexual groups earlier this year with his refusal to endorse gay couples as potential foster parents.

In toned-down platform language, the Democrats avoid using the words gay rights and instead affirm “equal access … for every citizen regardless of race, sex, national origin, religion, age, handicapping condition or sexual orientation.” Likewise, the platform avoids the word abortion, choosing instead the phrase “reproductive choice.

Party Of The Unborn?

Although the abortion issue was not acknowledged within the convention proceedings, it may prove to be a key to the party’s efforts to attract evangelicals. And in spite of the Democrats’ avoidance of the issue, critics attacked what they say is a definite proabortion tilt of the party standard-bearers.

At a press conference, the National Right to Life Committee (NRLC) called the Dukakis/Bentsen ticket “without question the most dedicated proabortion national ticket that has ever existed in history.” Calling Dukakis an abortion “zealot,” NRLC President Jack Willke outlined the governor’s aggressive abortion policies during his tenure in Massachusetts.

The NRLC also charged Bentsen with “misrepresenting” his abortion policies. According to statements from Bentsen’s office, the senator is “against abortion and has voted against abortion funding.” Yet, Planned Parenthood, in assessing 50 abortion-related votes in Congress between 1974 and 1986, found that Bentsen voted prochoice 43 times, prolife twice, and was absent five times. The National Abortion Rights Action League has also declared Bentsen’s record on abortion as “very good.”

Many prolife Democrats feel continually alienated by their party. Jackie Schweitz, head of a new group called National Prolife Democrats, said the Democratic leadership and platform is “out of step with the average Democrat” on the abortion issue. Citing several polls that found the majority of Democrats oppose unrestricted abortion, Schweitz said the Democrats’ position will hurt them in November. “Once prolife voters find out that Dukakis and Bentsen are proabortion, millions of Democratic voters will not be able to support the ticket and the Democratic party will once again lose,” she said.

As a prolife protest, Schweitz and two other uncommitted delegates from Minnesota voted for prolife Congressman Richard Stallings during the presidential roll call.

Room For Religion

While the Democrats have been emphasizing family values attractive to the evangelical community, there has been no concerted effort within the party specifically to target conservative Christians. Conservative religious groups were not granted the opportunity to present oral testimony during the Democrats’ platform molding process (CT, July 15, 1988, pp. 41–12).

Aside from the daily invocations and benedictions, religion and religious themes were largely absent from this year’s convention. Jesse Jackson, known for his frequent use of biblical imagery in his speeches, praised God for allowing him to be at the convention, and reminded the delegates that “red, yellow, brown, black, and white, we’re all precious in God’s sight.”

Apart from Jackson, however, the only other biblical reference in a speech was made by Sen. John Glenn (D-Ohio), who praised the separation of church and state and criticized the influence of conservative religious leaders on the Reagan administration. “The last thing we need is the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John rewritten by Meese, Bakker, Swaggart, and Falwell,” he said.

Nonetheless, Democratic activists assert there is room in their party for Christians. “In fact,” said Iowa delegate Richard Hodgson, “If [Christians] don’t get in here and try to leaven the loaf, they’re making a big mistake.” Hodgson, an Orthodox Presbyterian minister and science professor at Dordt College in Sioux Center, said he has “always felt Democrats were glad to welcome me, even as an evangelical, even as one who disagrees with them on some issues.”

Hodgson admits one of those issues is abortion. Although he is prolife, Hodgson said he also believes “it would be a mistake to say everything stands or falls on this one issue.” For Hodgson, the Democrats take a more compassionate stand on behalf of those already born. “When I … look for candidates who are really caring about people, I find most of them in the Democratic party,” he said.

Phillip Malebranche, a delegate representing Americans Abroad, agrees that Christians belong in the Democratic party. “If some doors [in the party] have recently been closed to Christians, I believe Christians have to keep pounding on those doors,” he said.

No Kidding

Not all profamily advocates have been happy with the “family talk” coming from the Democratic party. A coalition of conservative profamily groups held a “Family Forum ‘88” in Atlanta prior to the convention to address competing views of the family.

In the assessment of Family Research Council President Jerry Regier, two distinct visions of the family are emerging within both parties: one that places parental responsibility far above government intervention in family matters, and one that would give the government more responsibility in solving family problems. Family Forum sponsors favor the first vision, but believe the second is more predominant among current Democratic leadership.

The primary issue of concern at the conference was child care—an issue that has risen to the top of the national agenda this election year. Family Forum organizers were particularly critical of the heavily Democratic-sponsored Act for Better Child Care (ABC) bill now in Congress. Eagle Forum President Phyllis Schlafly called the act “the most antireligious bill ever introduced into Congress” and charged that it would set up a “Bureau of Babysitting” within the federal government. Schlafly and the other Family Forum members instead support child-care tax credits for all families with children, including those where one parent stays at home.

Membership of the Family Forum groups is largely made up of evangelicals and conservative Catholics, two key components of the “Reagan Democrats.” During the conference, Family Forum organizers released a “Family Manifesto,” promoting traditional values. Jerry Falwell noted in his address that these groups potentially have a great importance in the coming election. Saying they make up the “largest voting bloc in the nation,” Falwell declared that no president can be elected without their support.

A similar Family Forum meeting was also held at the Republican convention in New Orleans.

Religious Credentials

Thanks to the efforts of Jesse Jackson, the Democrats can probably count on the support of large segments of one Christian community: the black church. Throughout his campaign, Jackson used black churches as headquarters for stump speeches and fund raising. Although some political pundits had suggested Jackson supporters would walk away from the party because of the Dukakis campaign’s handling of the vice-presidential slot, Jackson seems to have forestalled such a walk.

South Carolina African Methodist Episcopal Bishop Frederick C. James said he and others in his denomination are taking their cue from Jackson. “He expressed a sense of satisfaction with how he related to Mr. Dukakis, … and I stand by his statement,” James said.

James, who led a benediction prayer at the convention, said AME members who supported Jackson “will work hard for the Democratic ticket because of the platform and the involvement of the Democratic party as it relates to black Americans.”

Another religious community, the Greek Orthodox Church, appears largely supportive of the Democratic party and of its favorite son. Michael Dukakis has been somewhat reticent to discuss his religious views publicly. “My own feelings about religion and my own church are very personal to me,” he said. Dukakis said he is a “good member of the Greek Orthodox Church,” and attends church “10, 12, 14 times a year.” His wife, Kitty, is Jewish, and Dukakis said they “respect each other’s religious tradition and belief” and have raised their children “in both cultures.”

Lloyd Bentsen, a Presbyterian, has a few more ties to the evangelical community. A supporter of congressional voluntary school prayer amendments, Bentsen has attended prayer breakfasts sponsored by the National Religious Broadcasters and has spoken at a National Association of Evangelicals (NAE) federal seminar meeting.

The extent to which the Democrats will be able to translate their efforts into evangelical votes remains to be seen. Yet, in a close election, this task may prove crucial. The NAE thinks an evangelical voting bloc could account for 2.5 percent of the total vote—enough to have reversed the outcome of four presidential elections since World War II.

By Kim A. Lawton in Atlanta.